Pierre Bernard (yogi)

Pierre Arnold Bernard (October 31, 1875 – September 27, 1955) — known as "The Great Oom", "The Omnipotent Oom" and "Oom the Magnificent"[1] — was a pioneering American yogi, scholar, occultist, philosopher, mystic and businessman.

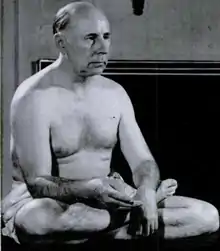

Pierre Bernard | |

|---|---|

Bernard in 1939 | |

| Born | Perry Arnold Baker 31 October 1875 Leon, Iowa, United States |

| Died | 27 September 1955 (aged 79) New York City, United States |

| Spouse(s) | Blanche DeVries Bernard |

Biography

Due to his practice of keeping his origins obscure, little is known for certain about his early life. He is reported to have been born Perry Arnold Baker[2] or Peter Coon[3] in Leon, Iowa, 31 October 1875,[4] the son of a barber.[5] He also called himself Homer Stansbury Leeds at some point.[5]

Bernard was trained in yoga by an accomplished Tantric yogi known as Sylvais Hamati, under whom Bernard studied for years.[6] He met Hamati in Lincoln, Nebraska in the late 1880s and they travelled together.[6] Hamati taught Bernard body-control techniques of hatha yoga. After several years of study, Bernard was able to put himself into deep trance, so his body could be pierced with long surgical needles.[7] He gave a public demonstration of what he termed the "Kali Mudra", a simulating death trance in January, 1898 to a group of physicians in San Francisco.[7] During the demonstration Dr. D. McMillan inserted a surgical needle "slowly through one of Bernard's earlobes". Needles were also pushed through his cheek, upper lip and nostril.[7] Bernard was featured on January 29, 1898, on the front page of The New York Times.[6]

Bernard took interest in hypnotism.[6] In 1905, he founded the Bacchante Academy with Mortimer K. Hargis to teach hypnotism and sexual practices. The organization declined because of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and their partnership dissolved.[8]

Bernard claimed to have traveled to Kashmir and Bengal before founding the Tantrik Order of America in 1905 or 1906,[4][9] variously reported as starting in San Francisco, Seattle, Tacoma, Washington, or in Portland, Oregon; the New York Sanskrit College in 1910; and the Clarkstown Country Club (originally called the Braeburn Country Club), a seventy-two acre estate with a thirty-room mansion[10] in Nyack, New York, a gift from a disciple,[5] in 1918. He eventually expanded to a chain of tantric clinics in places such as Cleveland, Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York City. Bernard is widely credited with being the first American to introduce the philosophy and practices of yoga and tantra to the American people.[4] He also played a critical role in establishing a greatly exaggerated association of tantra with the use of sex for mystical purposes in the American mindset.[10]

.png.webp)

In 1910, two teenage girls, Zella Hopp and Gertrude Leo,[5] feeling that he had taken too much psychic control over their lives, had him charged with kidnapping (alleging that Leo had been prevented three times from leaving the institute)[5] and briefly imprisoned.[10] Hopp reported that, for a pre-induction, Bernard had her strip and placed his hand upon her left breast, explaining that he was testing her heartbeat. "I cannot tell you how Bernard got his control over me or how he gets it over other people. He is the most wonderful man in the world. No women seem able to resist him.... He had promised to marry me many times. But when he began the same thing with my little sister [Mary, age sixteen] I decided I would expose the whole matter. If it had only been myself I wouldn't have done it for the whole world." Three months later, the charges were dropped.[5]

He remained popular with upper middle class women and the high society of New York throughout the 1920s and 30s. He married Blanche de Vries, who taught yoga in New York into her eighties,[4] combining yoga with Eastern-inspired sensual dance and contributing to a shift in attitudes about women's autonomy and sexuality.[2] Historian of religion Robert C. Fuller, has commented that Bernard's "sexual teachings generated such scandal that he was eventually forced to discontinue his public promulgation of Tantrism. Yet by this time Bernard had succeeded in making lasting contributions to the history of American alternative spirituality."[11] In his The Story of Yoga, the cultural historian Alistair Shearer acknowledges Bernard's importance, but states that he gave yoga a bad reputation, calling him a "roguey yogi".[12]

Bernard trained boxer Lou Nova in yoga.[13][14] Bernard was involved with more conventional businesses, including baseball stadiums, dog tracks, an airport, and became president of the State Bank of Pearl River in 1931.[10]

Lecturers at the Clarkstown Country Club included Ruth Fuller Everett and Leopold Stokowski. Among Bernard's students there was Ida Pauline Rolf.[15] Scholars from across the US visited Bernard's library, said to have been the best Sanskrit collection in the country and to contain some 7000 volumes of philosophy, ethics, psychology, education, metaphysics, and related material on physiology and medicine, to do research.[16]

Family

He was uncle of Theos Bernard,[17] an American scholar of religion, explorer and famous practitioner of Hatha Yoga and Tibetan Buddhism.

His half-sister Ora Ray Baker (Ameena Begum) married Inayat Khan after they met in 1912 at Bernard's Sanskrit College, and she subsequently became the mother of Sufi teacher Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan (1916-2004), World War II spy Noor-un-Nissa Inayat Khan (1914-1944), Hidayat Inayat Khan (1917-2016) and Khair-un-Nisa (Claire) (1919-2011).[18]

Publications

Bernard published the International Journal: Tantrik Order. Only one issue was published in 1906.[19][20]

- International Journal: Tantrik Order 1 (5).

- Vira Sadhana: A Theory and Practice of Veda (American Import Book Company, 1919)

Notes

- Stirling 2006, pg. 6

- Laycock 2013.

- Tantra in America

- Stirling 2006, pg. 7

- Pierre Arnold Bernard

- Kripal, Jeffrey J. (2007). Remembering Ourselves: On Some Countercultural Echoes of Contemporary Tantric Studies. Religions of South Asia 1.1: 11-28.

- Weir, David. (2011). American Orient: Imagining the East from the Colonial Era through the Twentieth Century. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-55849-879-2

- Melton, J. Gordon. (1999). Religious leaders of America: A Biographical Guide to Founders and Leaders of Religious Bodies, Churches, and Spiritual Groups in North America. Gale Research. p. 52. ISBN 978-0810388789

- Lattin, Don (August 19, 2013). "The Father of Tantra — Pierre Bernard". Spirituality & Health.

- Urban, Hugh B. (2001). The Omnipotent Oom: Tantra and its Impact on Modern Western Esotericism. Esoterica: The Journal of Esoteric Studies 3: 218-259.

- Fuller, Robert C. (2008). Spirituality in the Flesh: Bodily Sources of Religious Experiences. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-536917-5

- Shearer, Alistair (2020). The Story of Yoga: From Ancient India to the Modern West. London: Hurst Publishers. pp. 141–150. ISBN 978-1-78738-192-6.

- Sann, Paul. (1967). Fads, Follies, and Delusions of the American People. Crown Publishers. p. 186

- Love, Robert. (2010). The Great Oom: The Improbable Birth of Yoga in America. Viking. p. 289. ISBN 978-0670021758

- Stirling 2006, pg. 8

- Library of Pierre Arnold Bernard

- "The Life and Works of Theos Bernard". Columbia University. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- de Jong-Keesing, Elisabeth (1974). Inayat Khan. A Biography. East-West Publications. pp. 106, 119. ISBN 978-0-7189-0243-8.

- Anonymous. (1908). The Tantrik Order in America. Historic Magazine and Notes and Queries 26: 163.

- "Journal of the Tantrick Order". The International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals.

References

- Stirling, Isabel (2006), Zen Pioneer: The Life & Works of Ruth Fuller Sasaki; Counterpoint.

- Love, Robert (2010). The Great Oom: The Improbable Birth of Yoga in America. Viking. ISBN 978-0670021758.

- Laycock, Joseph (2013). "Yoga for the New Woman and the New Man: The Role of Pierre Bernard and Blanche DeVries in the Creation of Modern Postural Yoga". Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation. 23 (1): 101–136. doi:10.1525/rac.2013.23.1.101. JSTOR 10.1525/rac.2013.23.1.101.