Political status of Transnistria

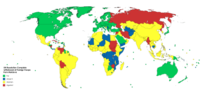

The political status of Transnistria, a self-proclaimed state on the internationally recognized territory of Moldova, has been disputed since the Transnistrian declaration of independence on 2 September 1990. This declaration sought to establish a Soviet Socialist Republic that would be independent from local Moldovan authority. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union and Moldova's own declaration of independence in 1991, the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (PMSSR) was transformed into the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR). However no United Nations member country recognizes the PMR's independence.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Transnistria |

| See also |

The Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic obtained diplomatic recognition only from Abkhazia, South Ossetia and the Artsakh, three post-Soviet states with minimal recognition themselves.

Historical status of Transnistria

Until the Second World War

Although ethnic Moldavians have historically made up a large minority of the population, the area was never considered part of the traditional lands of Moldavian settlement.[1] The territory east of the Dniester River belonged to Kievan Rus' and the kingdom of Halych-Volhynia from the ninth to the fourteenth centuries, passing to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and then into the hands of Russia in the eighteenth century.

By this time, the Principality of Moldavia had been in existence for almost five hundred years with the Dniester marking its eastern boundary for all this time.

Even with the rise of Romanian irredentism in the nineteenth century, the far reaches of Transylvania were considered the western boundary of the Greater Romanian lands[1] while the Dniester formed the eastern.[2] The national poet Mihai Eminescu, in his famous poem Doina, spoke of a Romania stretching "from the Dniester to the Tisza".

The Soviet Union in the 1930s had an autonomous region of Transnistria inside Ukraine, called the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (MASSR), where nearly half of the population were neolatin speaking people, and with Tiraspol as its capital.

During World War II, when Romania, aided by Nazi Germany, took control of Transnistria, it made no attempts to annex the occupied territory. It was considered a temporary buffer zone between Greater Romania and the Soviet front line.[3][4]

Territorial Consequences of 1992 Conflict

- Eastern Bank of the Dniester

During the 1992, War of Transnistria some villages in the central part of Transnistria (on the eastern bank of the Dniester), rebelled against the new separatist Transnistria (PMR) authorities. They have been under effective Moldovan control as a consequence of their rebellion against the PMR. These localities are: commune Cocieri (including village Vasilievca), commune Molovata Nouă (including village Roghi), commune Corjova (including village Mahala), commune Coşniţa (including village Pohrebea), commune Pîrîta, and commune Doroţcaia. The village of Corjova is in fact divided between PMR and Moldovan central government areas of control. Roghi is also controlled by the PMR authorities.

- Right bank of the Dniester

At the same time, some areas which are situated on the right bank of the Dniester are under PMR control. These areas consist of the city of Bender with its suburb Proteagailovca, the communes Gîsca, Chiţcani (including villages Mereneşti and Zahorna), and the commune of Cremenciug, formally in the Căuşeni District, situated south of the city of Bender.

The breakaway PMR authorities also claim the communes of Varniţa, in the Anenii Noi District, a northern suburb of Bender, and Copanca, in the Căuşeni District, south of Chiţcani, but these villages remain under Moldovan control.

Later Tensions

Several disputes have arisen from these cross-river territories. In 2005 PMR Militia entered Vasilievca, which is located over the strategic road linking Tiraspol and Rîbniţa, but withdrew after a few days.[5][6] In 2006 there were tensions around Varniţa. In 2007 there was a confrontation between Moldovan and PMR forces in the Dubăsari-Cocieri area; however, there were no casualties. On the 13th of May 2007, the mayor of the village of Corjova, which is under Moldovan control, was arrested by the PMR militsia (police) together with a councilor of Moldovan-controlled part of the Dubăsari district.[7]

Political ideologies in Transnistria

The two main political parties in Transnistria, the Republican Party (Respublikanskaya Partiya Pridnestroviya) and Renewal (Obnovleniye) oppose any rapprochement with Chişinău. The only party that has been in favor of some conditional rapprochement with Moldova is the Social Democratic Party, it however lost its influence in 2009 and ceased to function.

Negotiations under the auspices of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) have been ongoing since 1997. The main premise on which these negotiations are based is that better relations between the PMR and Moldova are desirable. Furthermore the OSCE advocates for the removal of restrictions on communications, movement of people, and trade flows.

Position of the PMR government advocates

According to PMR advocates, the territory to the East of the Dniester River never belonged either to Romania, nor to its predecessors, such as the Principality of Moldavia. This territory was split off from the Ukrainian SSR in a political maneuver of the USSR to become a seed of the Moldavian SSR (in a manner similar to the creation of the Karelo-Finnish SSR). In 1990, the Pridnestrovian Moldavian SSR was proclaimed in the region by a number of conservative local Soviet officials opposed to perestroika. This action was immediately declared void by the then president of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev.[8]

At the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Moldova became independent. The Moldovan Declaration of Independence denounced the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and declared the 2 August 1940 "Law of the USSR on the establishment of the Moldavian SSR" null and void. The PMR side argues that, since this law was the only legislative document binding Transnistria to Moldova, there is neither historical nor legal basis for Moldova's claims over the territories on the left bank of the Dniester.[9] The Transnistrian side also claims that the rights of Moldova's Russian-speaking population are being infringed as Moldovan authorities abolished Russian as a second official language and declared Romanian (Moldovan) to be the country's only official language shortly before the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

A 2010, study conducted by the University of Colorado Boulder showed that the majority of Transnistria's population supports the country's separation from Moldova. According to the study, more than 80% of ethnic Russians and Ukrainians, and 60% of ethnic Moldovans, in Transnistria preferred independence or annexation by Russia rather than reunification with Moldova.[10]

In 2006, officials of the country decided to hold a Referendum to get a hold of what the population wanted with regards to the status of Transnistria. They were asked to indicate if they were in favor or against of two statements. The first one being "Renouncing independence and potential future integration into Moldova" and the second one being "Independence and potential future integration into Russia". The results of this double referendum were that a large section of the population was against the first statement (96, 61%)[11] and in favor of the second one (98,07%).[12]

Political officials have ever since used the results of this referendum to advocate for official recognition and independence from the international community.

Moldovan position

Moldova lost de facto control of Transnistria in 1992, in the wake of the War of Transnistria. However, the Republic of Moldova considers itself the rightful successor state to the Moldavian SSR (which was guaranteed the right to secession from the Soviet Union under the last version of the Soviet Constitution). By the principle of territorial integrity, Moldova claims that any form of secession from the state without the consent of the central Moldovan government is illegal. The Moldavia side hence believes that its position is backed by international law [13]

It considers the current Transnistria-based PMR government to be illegitimate and not the rightful representative of the region's population, which has a Moldovan plurality (39.9% as of 1989).[14] The Moldovan side insists that Transnistria cannot exist as an independent political entity and must be reintegrated into Moldova.

According to Moldovan sources, the political climate in Transnistria does not allow the free expression of the will of the people of the region and supporters of reintegration of Transnistria in Moldova are subjected to harassment, arbitrary arrests and other types of intimidation from separatist authorities.

.jpg.webp)

Because of the nonrecognition of Transnistrian's independence, Moldova believes that all inhabitants of Transnistria are legally speaking, citizens of Moldova. However, it is estimated that 60 000 to 80 000 inhabitants of Transistria acquired Russian citizenship [15] and around 20 000 Transnistrian have acquired Ukrainian citizenship. As a result, Moldovan authorities have tried to block the installation of a Russian and Ukrainian consulate in Tiraspol [16]

International Recognition of the sovereignty of Transnistria

Only three polities recognize Transnistria's sovereignty, which are themselves largely unrecognized states: Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Artsakh. All four states are members of the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations.

United Nations Resolution A/72/L.58

On 22 June 2018, the Republic of Moldova submitted a UN resolution that calls for "Complete and unconditional withdrawal of foreign military forces from the territory of the Republic of Moldova, including Transnistria."[17]

See also

Notes

- Charles King: The Moldovans, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, California, 1999, page 180

- Nicolas Dima's history of Moldova, published in 1991 as part of a series of East European Monographs, Boulder, Distributed by Columbia University Press, New York.

- Charles King: "The Moldovans", Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, California, 1999, page 93

- Memoirs of Gherman Pântea, mayor of Odessa 1941–1944, in ANR-DAIC, d.6

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-05-14. Retrieved 2006-12-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2005-03-18. Retrieved 2007-01-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2016-02-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-09-27. Retrieved 2010-09-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-06-17. Retrieved 2010-09-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "How people in South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria feel about annexation by Russia". Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-12-17.

- ch, Beat Müller, beat (at-sign) sudd (dot). "Transnistrische Moldawische Republik (Moldawien), 17. September 2006 : Verzicht auf Unabhängigkeit -- [in German]". www.sudd.ch. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- ch, Beat Müller, beat (at-sign) sudd (dot). "Transnistrische Moldawische Republik (Moldawien), 17. September 2006 : Unabhängigkeitskurs und Beitritt zu Russland -- [in German]". www.sudd.ch. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- "Looking for a Solution Under International Law for the Moldova – Transnistria Conflict". Opinio Juris. 2020-03-17. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Transnistria (unrecognised state)". Refworld. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Moldova and Russia: Whether a holder of Ukrainian citizenship, born in Tiraspol, could return to Tiraspol and acquire Russian citizenship (2005)". Refworld. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Moldova and Russia: Whether a holder of Ukrainian citizenship, born in Tiraspol, could return to Tiraspol and acquire Russian citizenship (2005)". Refworld. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- "General Assembly of the United Nations". www.un.org. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

References

- Oleksandr Pavliuk, Ivanna Klympush-Tsintsadze. The Black Sea Region: Cooperation and Security Building. EastWest Institute. ISBN 0-7656-1225-9.

- Janusz Bugajski. Toward an Understanding of Russia: New European Perspectives. p. 102. ISBN 0-87609-310-1.

- "Transnistria: alegeri nerecunoscute". Ziua. 13 December 2005. Archived from the original on 30 June 2006.

- James Hughes; Gwendolyn Sasse (eds.). Ethnicity and Territory in the Former Soviet Union: Regions in conflict. Routledge Ed. ISBN 0-7146-5226-1.

External links

- Transnistrian side

- History of creation and development of the Parliament of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR)

- Moldovan side

- EuroJournal.org's Transnistria category

- Trilateral Plan for Solving the Transnistrian Issue (developed by Moldova-Ukraine-Romania expert group)

- Others

- International organizations

- OSCE Mission to Moldova: Conflict resolution and negotiation category

- Marius Vahl and Michael Emerson, "Moldova and the Transnistrian Conflict" (pdf) in "Europeanization and Conflict Resolution: Case Studies from the European Periphery", JEMIE - Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 1/2004, Ghent, Belgium

- Research on the European Union and the conflict in Transnistria

- New York City Bar: Russia’s Activities in Moldova Violate International Law

- Ukrainian side

- Romanian side

- Viroel Dolha. "All About Transnistria (I)". Newsgroup: Soc.culture.romanian. Usenet: [email protected].