Priscomyzon

Priscomyzon riniensis is an extinct lamprey that lived some 360 million years ago during the Famennian (Late Devonian) in a marine or estuarine environment in South Africa. This small agnathan is anatomically similar to the Mazon Creek lampreys, but is some 35 million years older. Its key developments included the first known large oral disc, circumoral teeth and a branchial basket.

| Priscomyzon | |

|---|---|

| |

| holotype | |

| |

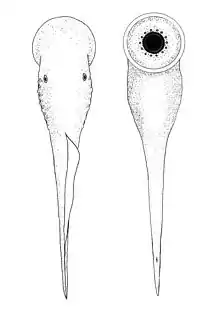

| Line drawing reconstruction | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Genus: | Priscomyzon Gess et al., 2006 |

| Type species | |

| Priscomyzon riniensis Gess et al., 2006 | |

Context

Though common and diverse during the Silurian and Devonian, jawless fish are today represented only by lampreys and hagfish, both groups being quite specialized. Lampreys have seven gill pouches (whereas jawed fish have only five), no paired fins, and a rudimentary skeleton of cartilage. They also have a sucker disc of cartilage surrounded by a soft lip and a central small mouth set about with simple hooked teeth. They attach to the bodies of other vertebrates by suction, securing their grip with the hooked teeth, after which a rasped tongue scrapes a hole providing access to the host's softer tissues.

Implications of the find

Priscomyzon provides evidence that agnathans close to modern lampreys had existed before the end of the Devonian period. Lampreys have ancient origins, have endured for 360 million years and lived through four major extinction events - even so, their evolutionary history is obscure. In ancient seas jawless vertebrate fish led to jawed fish, and thence to all other vertebrates, including humans. Being the only extant jawless vertebrates and a virtual time capsule of embryology and DNA, lampreys and hagfish are of immense scientific interest.[1] Knowing the period during which they became parasitic would shed light on how typical they are of ancient fish. Having no bone tissue, effectively being essentially boneless, their cartilaginous framework leaves almost no fossil record - a mere three fossil species had previously been described, and in none of these was a sucker disc detected.

Description

The exceptionally well-preserved fossil of P. riniensis is only 42mm long and reveals details of its fin, gill basket and mouth region. A striking feature of Priscomyzon is its relatively large oral disk, inside a soft outer lip, supported by annular cartilage. The circular mouth at the center of the oral disk is surrounded by 14 small, evenly spaced, simple teeth, with no associated radiating series or plates of supplementary teeth, but otherwise quite similar to present-day lampreys, suggesting that their blood-sucking lifestyle was developed in ancient seas. The oral disk of the Late Carboniferous lamprey Mayomyzon pieckoensis, if present, is much smaller, while there is no evidence of a disk in the Early Carboniferous Hardistiella montanensis. Priscomyzon's are the earliest teeth found in any fossil lamprey, and have a similar arrangement to that of the 19 or more teeth found in modern forms such as Ichthyomyzon, Petromyzon, Caspiomyzon and Geotria.

Its posterior teeth are more elongate than the rest, while in modern species lateral or anterior teeth tend to be largest. Its teeth are also quite simple in shape compared to those of modern species, and in this respect are probably primitive. The position of the orbits is not clear as there are no darkened areas suggesting eye locations. The branchial imprint is preserved in great detail, parts of both the right and left baskets having been preserved, and the posterior five branchial arches being well defined. Anterior to these the presence of seven branchial pouches is evident. The dorsal fin originates immediately behind the branchiae and continues to the caudal extremity, resembling a modern ammocoete or lamprey larva rather than an adult, in which separate anterior and posterior dorsal fins are to be found.

Discovery

The lamprey fossil was discovered on Waterloo Farm in rocks of the Witteberg Group near Grahamstown in South Africa. The species was described by Robert W. Gess & Bruce S. Rubidge of the Bernard Price Institute (Palaeontology) Wits University, and Michael I. Coates of the Department of Organismal Biology University of Chicago in the journal Nature of 26 October 2006. The shale containing the fossil was discovered as far back as 1985 during construction of the N2 bypass outside Grahamstown. The site consists of black carbonaceous shale formed from anaerobic mud deposited in a marine estuary on the Agulhas Sea. A variety of organic remains are found in this setting, including algae, terrestrial plants and fish. Invertebrate remains are of small bivalves, ostracods, clam shrimp, and a eurypterid. Fossil material has been greatly compressed and original tissue replaced by metamorphic mica altered to chlorite during uplift. To prevent rockfalls onto the road from the unstable formation, the steep slopes were cut back again in 1999 and once more in 2007/8. During these upgrades Gess managed to obtain a large sample of rock blocks with the help of the road construction company, and worked intermittently on exposing their contents.

Etymology

The scientific name derives from the Latin priscus "ancient", and Greek myzon "sucking". 'Rini' is the isiXhosa name for Grahamstown and its surrounding valley.

Holotype

The holotype is held in the Albany Museum, Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, with the catalogue number AM5750. The locality and horizon is the Waterloo Farm, Grahamstown, South Africa; Witpoort Formation, Witteberg Group, Famennian, Late Devonian.

References

- "Discovery of the oldest fossil lamprey in the world" Archived 2013-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Gess, Robert W.; Coates, Michael I.; Rubidge, Bruce S. (2006). "A lamprey from the Devonian period of South Africa". Nature. 443 (7114): 981–984. doi:10.1038/nature05150. PMID 17066033.