Red Orchestra (espionage)

The Red Orchestra (German: Die Rote Kapelle, German: [ˈʁoː.tə kaˈpɛ.lə] (![]() listen)), as it was known in Germany, was the name given by the Abwehr Section III.F to anti-Nazi resistance workers in August 1941. It primarily referred to a loose network of resistance groups, connected through personal contacts, uniting hundreds of opponents of the Nazi regime. These included groups of friends who held discussions that were centred around Harro Schulze-Boysen, Adam Kuckhoff and Arvid Harnack in Berlin, alongside many others. They printed and distributed prohibited leaflets, posters, and stickers, hoping to incite civil disobedience. Aided Jews and resistance escape the regime, documented the atrocities of the Nazis, and transmitted military intelligence to the Allies. Contrary to legend, the Red Orchestra was neither directed by Soviet communists nor under a single leadership. It was a network of groups and individuals, often operating independently. To date, about 400 members are known by name.[1][2]

listen)), as it was known in Germany, was the name given by the Abwehr Section III.F to anti-Nazi resistance workers in August 1941. It primarily referred to a loose network of resistance groups, connected through personal contacts, uniting hundreds of opponents of the Nazi regime. These included groups of friends who held discussions that were centred around Harro Schulze-Boysen, Adam Kuckhoff and Arvid Harnack in Berlin, alongside many others. They printed and distributed prohibited leaflets, posters, and stickers, hoping to incite civil disobedience. Aided Jews and resistance escape the regime, documented the atrocities of the Nazis, and transmitted military intelligence to the Allies. Contrary to legend, the Red Orchestra was neither directed by Soviet communists nor under a single leadership. It was a network of groups and individuals, often operating independently. To date, about 400 members are known by name.[1][2]

The term was also used by the German Abwehr to refer to unassociated Soviet intelligence networks, working in Belgium, France and the low countries, that were built up by Leopold Trepper on behalf of the Main Directorate of State Security (GRU).[3] Trepper ran a series of clandestine cells for organising agents.[4] Trepper used the latest technology, in the form of small wireless radios to communicate with Soviet intelligence.[4] Although the monitoring of the radios transmissions by the Funkabwehr would eventually lead to the organisation's destruction, the sophisticated use of the technology-enabled the organisation to behave as a network, with the ability to achieve tactical surprise and deliver high-quality intelligence, including the warning of Operation Barbarossa.[4]

To this day, the German public perception of the "Red Orchestra" is characterized by the vested interest historical revisionism of the post-war years and propaganda efforts of both sides of the Cold War.[5]

_Rote_Kapelle_Achim_K%C3%BChn_2010.jpg.webp)

Reappraisal

For a long time after World War II, only parts of the German resistance to Nazism had been known to the public within Germany and the world at large.[6] This included the groups that took part in the 20 July plot and the White Rose resistance groups. In the 1970s there was a growing interest in the various forms of resistance and opposition. However, no organisations' history was so subject to systematic misinformation, and recognised as little, as those resistance groups centred around Arvid Harnack and Harro Schulze-Boysen.[6]

In a number of publications, the groups that these two people represented were seen as traitors and spies. An example of these was Kennwort: Direktor; die Geschichte der Roten Kapelle (Password: Director; The history of the Red Orchestra) written by Heinz Höhne who was a Der Spiegel journalist.[6] Höhne based his book on the investigation by the Lüneburg Public Prosecutor's Office against the General Judge of the Luftwaffe and Nazi apologist Manfred Roeder who was involved in the Harnack and Schulze-Boysen cases during World War II and who contributed decisively to the formation of the legend that survived for much of the Cold War period. In his book Höhne reports from former Gestapo and Reich war court individuals who had a conflict of interest and were intent in defaming the groups attached to Harnack and Schulze-Boysen with accusations of treason.[6]

The perpetuation of the defamation from the 1940s through to the 1970s that started with the Gestapo, was incorporated by the Lüneburg Public Prosecutor's Office and evaluated as a journalistic process that can be seen by the 1968 trial of far-right holocaust denier Manfred Roeder by the German lawyer Robert Kempner. The Frankfurt public prosecutor's office, which prosecuted the case against Roeder, based its investigation on procedure case number "1 Js 16/49" which was the trial case number defined by the Lüneburg Public Prosecutor's Office.[6] The whole process propagated the Gestapo ideas of the Red Orchestra and this was promulgated in the report of the public prosecutor's office which stated:[6]

To these two men and their wives, a group of political supporters of different characters and of different backgrounds gathered over the course of time. They were united in the active fight against National Socialism and in their advocacy of communism (emphasis added by author). Until the outbreak of the war with the Soviet Union, the focus of their work was on domestic politics. After that, he shifted more to the territory of treason and espionage in favor of the Soviet Union. At the beginning of 1942, the Schulze-Boysen Group was finally involved in the widespread network of the Soviet intelligence service in Western Europe. [...] The Schulze-Boysen group was first and foremost an espionage organization for the Soviet Union.

From the perspective of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) the Red Orchestra were honoured as anti-fascist resistance fighters and indeed received posthumous orders in 1969. However, the most comprehensive collection of biographies that exist are from the GDR and they represent their point of view, through the lens of ideology.[6]

In the 1980s, the GDR historian Heinrich Scheel, who at the time was vice president of the East German Academy of Sciences and who was part of the anti-Nazi Tegeler group that included Hans Coppi, Hermann Natterodt and Hans Lautenschlager from 1933, conducted research into the Rote Kapelle and produced a paper which took a more nuanced view of the Rote Kapelle and discovered the work that was done to defame them. [7][6] Heinrich Scheel's work enabled a re-evaluation of the Rote Kapelle, but it was not until 2009 that the German Bundestag overturned the judgments of the National Socialist judiciary for "treason" and rehabilitated the members of the group.[8]

Name

The name Rote Kapelle was a cryptonym that was invented for a secret operation started by Abwehrstelle Belgium (Ast Belgium), a field office of Abwehr III.F in August 1941 and conducted against a Soviet intelligence station that had been detected in Brussels in June 1941.[9] Kapelle was an accepted Abwehr term for counter-espionage operations against secret wireless transmitting stations and in the case of the Brussels stations Rote was used to differentiate from other enterprises conducted by Ast Belgium.[9]

In July 1942, the case of the Red Orchestra was taken over from Ast Belgium by section IV. A.2. of the Sicherheitsdienst. When Soviet agent Anatoly Gurevich was arrested in November 1942,[10] a small independent unit made up of Gestapo personnel known as the Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle was formed in Paris in the same month and led by SS-Obersturmbannführer (Colonel) Friedrich Panzinger.

The Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA), the counter-espionage part of the Schutzstaffel (SS), referred to resistance radio operators as "pianists", their transmitters as "pianos", and their supervisors as "conductors".[11]

Only after the funkabwehr had decrypted radio messages in August 1942, in which German names appeared, did the Gestapo start to arrest and imprison them, their friends and relatives. In 2002, the German filmmaker Stefan Roloff, whose father was a member of one of the Red Orchestra groups,[12] wrote:

- Due to their contact with the Soviets, the Brussels and Berlin groups were grouped by the Counterespionage and the Gestapo under the misleading name Red orchestra. A radio operator tapping Morse code marks with his fingers was a pianist in the intelligence language. A group of "pianists" formed an "Orchestra", and since the Morse code had come from Moscow, the "Orchestra" was communist and thus red. This misunderstanding laid the foundation upon which the resistance group was later treated as a serving espionage organization in the historiography of the Soviets, until it could be corrected at the beginning of the 1990s. The Organization construct created by the Gestapo, Red Orchestra has never existed in this form.[13] In his research, the historian Hans Coppi Jr., whose father was also a member, Hans Coppi, emphasised that, in view of the Western European groups

- A network led by Leopold Trepper of the 'Red Orchestra' in Western Europe did not exist. The different groups in Belgium, Holland and France worked largely independently of each other.[3]

The German political scientist Johannes Tuchel summed up in a research article for the Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand.[14]

- The Gestapo investigates them under the collective name, Red Orchestra and wants it to be judged above all as a spy organization of the Soviet Union. This designation, which reduces the groups around Harnack and Schulze-Boysen on contacts to the Soviet intelligence service, also later shapes the motives and aims, later distorting their image in the German public.

Germany

Harnack group/Schulze-Boysen

The Red Orchestra in the world today are mainly the resistance groups around the Luftwaffe officer Harro Schulze-Boysen, the writer Adam Kuckhoff and the economist Arvid Harnack, to which historians assign more than 100 people.[14]

Origin

Harnack and Schulze-Boysen had similar political views, both rejected the Treaty of Versailles of 1919, and sought alternatives to the existing social order. Since the Great Depression of 1929, they saw the Soviet planned economy as a positive counter-model to the free-market economy. They wanted to introduce planned economic elements in Germany and work closely with the Soviet Union without breaking German bridges to the rest of Europe.

_1964%252C_MiNr_1017.jpg.webp)

Before 1933, Schulze-Boysen published the non-partisan leftist and later banned magazine German: Gegner, lit. 'opponent'.[15] In April 1933, the Sturmabteilung detained him for some time, severely battered him, and killed a fellow Jewish inmate. As a trained pilot, he received a position of trust in 1934 in the Reich Ministry of Aviation and had access to war-important information. After his marriage to Libertas Schulze-Boysen née Haas-Heye in 1936, the couple collected young intellectuals from diverse backgrounds, including the artist couple Kurt and Elisabeth Schumacher, the writers Günther Weisenborn and Walter Küchenmeister, the photojournalist John Graudenz (who had been expelled from the USSR for reporting the Soviet famine of 1932–1933) and Gisela von Pöllnitz, the actor Marta Husemann and her husband Walter in 1938, the doctors Elfriede Paul in 1937 and John Rittmeister in Christmas 1941, the dancer Oda Schottmüller, and since Schulze-Boysen held twice-monthly meetings at his Charlottenburg atelier for thirty-five to forty people in what was considered a Bohemian circle of friends. Initially, these meetings followed an informatics program of resistance that was in keeping with its environment and were important places of personal and political understanding but also vanishing points from an often unbearable reality, essentially serving as islands of democracy. As the decade progressed they increasingly served as identity-preserving forms of self-assertion and cohesion as the Nazi state became all-encompassing.[16] Formats of the meetings usually started with book discussions in the first 90 minutes were followed by Marxist discussions and resistance activities that were interspersed with parties, picnics, sailing on the Wannsee and poetry readings until midnight as the mood took.[17] However, as the realisation that the war preparations were becoming unstoppable and the future victors were not going to be the Sturmabteilung, Schulze-Boysen whose decisions were in demand called for the group to cease their discussions and start resisting.[16]

Other friends were found by Schulze-Boysen among former students of a reform school on the island of Scharfenberg in Berlin-Tegel. These often came from communist or social - democratic workers' families, e.g. Hans and Hilde Coppi, Heinrich Scheel, Hermann Natterodt and Hans Lautenschlager. Some of these contacts existed before 1933, for example through the German Society of intellectuals. John Rittmeister's wife Eva was a good friend of Liane Berkowitz, Ursula Goetze, Friedrich Rehmer, Maria Terwiel and Fritz Thiel who met in the 1939 abitur class at the secondary private school, Heil'schen Abendschule at Berlin W 50, Augsburger Straße 60 in Schöneberg. The Romanist Werner Krauss joined this group, and through discussions, an active resistance to the Nazi regime grew. Ursula Goetze who was part of the group, provided contacts with the communist groups in Neukölln.[8]

From 1932 onwards, the economist Arvid Harnack and his American wife Mildred assembled a group of friends and members of the Berlin Marxist Workers School (MASCH) to form a discussion group that debated the political and economic perspectives at the time.[18] Harnak's group meetings, in contrast to those of Schulze-Boysen's group, were considered rather austere. Members of the group included the German politician and Minister of Culture Adolf Grimme, the locksmith Karl Behrens, the German journalist Adam Kuckhoff and his wife Greta and the industrialist and entrepreneur Leo Skrzypczynski. From 1935, Harnack tried to camouflage his activities by becoming a member of the Nazi Party working in the Reich Ministry of Economics with the rank of Oberregierungsrat. Through this work, Harnack planned to train them to build a free and socially-just Germany after the end of the National Socialism' regime.[8]

Oda Schottmüller and Erika Gräfin von Brockdorff were friends with the Kuckhoffs. In 1937 Adam Kuckhoff introduced Harnack to the journalist and railway freight ground worker John Sieg, a former editor of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) newspaper the Die Rote Fahne. As a railway worker at the Deutsche Reichsbahn, Sieg was able to make use of work-related travel, enabling him to found a communist resistance group in the Neukölln borough in Berlin. He knew the former Foreign Affairs Minister Wilhelm Guddorf and Martin Weise.[19] In 1934 Guddorf was arrested and sentenced to hard labour. In 1939 after his release from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp,[17] Guddorf worked as a bookseller, and worked closely with Schulze-Boysen.[8]

Through such contacts, a loose network formed in Berlin in 1940 and 1941, of seven interconnected groups centered on personal friendships as well as groups originally formed for discussion and education. This disparate network was composed of over 150 Berlin Nazi opponents,[20] including artists, scientists, citizens, workers, and students from several different backgrounds. There were Communists, political conservatives, Jews, Catholics, and atheists. Their ages ranged from 16 to 86, and about 40% of the group were women. Group members had different political views, but searched for the open exchange of views, at least in the private sector. For instance, Schulze-Boysen and Harnack shared some ideas with the Communist Party of Germany, while others were devout Catholics such as Maria Terwiel and her husband Helmut Himpel. Uniting all of them was the firm rejection of national socialism.

This network grew up after Adam and Greta Kuckhoff introduced Harro and Libertas Schulze-Boysen to Arvid and Mildred Harnack, and the couples began engaging socially.[21] Their hitherto separate groups moved together once the Polish campaign began in September 1939.[22] From 1940 onwards, they regularly exchanged their opinions on the war and other Nazi policies and sought action against it.[8]

The historian Heinrich Scheel, a schoolmate of Hans Coppi, judged these groups by stating:

- Only with this stable hinterland, it was possible to get through all the little glitches and major disasters and to make permanent our resistance

As early as 1934, Scheel had passed written material from one contact person to the next within clandestine communist cells and had seen how easily such connections were lost if a meeting did not materialize due to one party being arrested. In a relaxed group of friends and discussion with like-minded people, it was easy to find supporters for an action. [23]

Acts of resistance

_1964%252C_MiNr_1018.jpg.webp)

From 1933 onwards, the Berlin groups connected to Schulze-Boysen and Harnack resisted the Nazis by:

- Providing assistance to the persecuted

- Disseminating pamphlets and leaflets that contained dissident content.

- Writing letters to prominent individuals including university professors.

- Collecting and sharing information, including on foreign representatives, on German war preparations, crimes of the Wehrmacht and Nazi crimes,

- Contacting other opposition groups and foreign forced labourers.

- Invoking disobedience to Nazi representatives.

- Writing drafts for a possible post-war order.

From mid-1936, the Spanish Civil War preoccupied the Schulze-Boysen group. Through Walter Küchenmeister, the Schulze-Boysen group began to discuss more concrete actions, and during these meetings would listen to foreign radio stations from London, Paris and Moscow.[22] A plan was formed to take advantage of Schulze-Boysen employment, and through this, the group were able to get detailed information on Germany's support of Francisco Franco. Beginning in 1937, in the Wilmersdorf waiting room of Dr. Elfriede Paul, began distributing the first leaflet on the Spanish Civil War.[24]

In the same year, Schulze-Boysen had compiled a document about a sabotage enterprise planned in Barcelona by the Wehrmacht "Special Staff W", an organization established by Helmuth Wilberg to analyse the tactical lessons learned by the Legion Kondor during the war.[25] The information that Schulze-Boysen collected included details about German transports, deployment of units and companies involved in the German defense.[26] Libertas's cousin, Gisela von Pöllnitz placed the letter in the mailbox of the Soviet Embassy on the Bois de Boulogne in Paris.[27]

After the Munich Agreement, Schulze-Boysen created a second leaflet with Walter Küchenmeister, that declared the annexation of the Sudetenland in October 1938 as a further step on the way to a new world war. This leaflet was called Der Stoßtrupp or The Raiding Patrol, and condemned the Nazi government and argued against the government's propaganda.[22] A document that was used at the trial of Schulze-Boysen indicated that only 40 to 50 copies of the leaflet were distributed.[22]

The Invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, was seen as the beginning of the feared world war, but also as an opportunity to eliminate Nazi rule and to a thorough transformation of German society. Hitler's victories in France and Norway in 1940 encouraged them to expect the replacement of the Nazi regime, above all from the Soviet Union, not from Western capitalism. They believed that the Soviet Union would keep Germany as a sovereign state after its victory and that they wanted to work towards a corresponding opposition without domination by the Communist Party of Germany.

Around 13 June 1941, Schulze-Boysen prepared a report that gave the final details of the Soviet invasion including details of Hungarian airfields containing German planes.[28] On the 17 June, the Soviet People's Commissar for State Security presented the report to Stalin, who harshly dismissed it as disinformation.[29]

In December 1941, John Sieg published The Internal Front (German:Die Innere Front) on a regular basis.[30] It contained texts by Walter Husemann, Fritz Lange, Martin Weise and Herbert Grasse, including information about the economic situation in Europe, references to Moscow radio frequencies, and calls for resistance. It was produced in several languages for foreign forced labourers in Germany.[31] Only one copy from August 1942 has survived.[32]

After the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, Hilde Coppi had secretly listened to Moscow radio in order to receive signs of life from German prisoners of war and to forward them to their relatives via Heinrich Scheel. This news contradicted the Nazi propaganda that the Red Army would murder all German soldiers who surrendered. In order to educate them about propaganda lies and Nazi crimes, the group copied and sent letters to soldiers on the Eastern Front, addressed to a fictitious police officer.[33]

In autumn 1941 the eyewitness Erich Mirek reported to Walter Husemann about mass murders of Jews by the SS and SD in Pinsk.[34] The group announced these crimes in their letters.

AGIS leaflets

From 1942 onwards, the group started to produce leaflets that were signed with AGIS in reference to the Spartan King Agis IV, who fought against corruption for his people.[37] Naming the newspaper Agis, was originally the idea of John Rittmeister.[38] The pamphlets had titles like The becoming of the Nazi movement, Call for opposition, Freedom and violence[39] and Appeal to All Callings and Organisations to resist the government.[40] The writing of the AGIS leaflet series was a mix of Schulze-Boysen and Walter Küchenmeister, a communist political writer, who would often include copy from KPD members and through contacts.

They were often left in phone booths or selected addresses from the phone book. Extensive precautions were taken, including wearing gloves, using many different typewriters and destroying the carbon paper. John Graudenz also produced, running duplicate mimeograph machines in the apartment of Anne Krauss.[41]

On 15 February 1942, the group wrote the large 6-page pamphlet called Die Sorge Um Deutschlands Zukunft geht durch das Volk! (English:The concern for Germany's future goes through the people!. The master copy was arranged by the potter Cato Bontjes van Beek and the pamphlet was written up by Maria Terwiel[42] on her typewriter, five copies at a time.[43] The paper describes how the care of Germany's future is decided by the people... and called for the opposition to the war the Nazis all Germans, who now all threaten the future of all. A copy survived to the present day. [44][45]

The text first analysed the current situation: contrary to the Nazi propaganda, most German armies were in retreat, the number of war dead was in the millions. Inflation, scarcity of goods, plant closures, labour agitation and corruption in State authorities were occurring all the time. Then the text examined German war crimes:

- The conscience of all true patriots, however, is taking a stand against the whole current form of German power in Europe. All who retained the sense of real values shudder when they see how the German name is increasingly discredited under the sign of the swastika. In all countries today, hundreds, often thousands of people, are shot or hanged by legal and arbitrary people, people to whom they have nothing to be accused of but to remain loyal to their country ... In the name of the Reich, the most abominable torments and atrocities are committed against civilians and prisoners. Never in history has a man been so hated as Adolf Hitler. The hatred of tortured humanity is weighing on the whole German people.[44]

The Soviet Paradise exhibition

In May 1942, Joseph Goebbels held a Nazi propaganda exhibition called The Soviet Paradise (German original title "Das Sowjet-Paradies")[46] in Lustgarten, with the express purpose of justifying the invasion of the Soviet Union to the German people.[47]

Both the Harnacks and Kuckhoffs spent half a day at the exhibition. For Greta Kuckhoff particularly and her friends, the most distressing aspect of the exhibition was the installation about SS measures against Russian "partisans" (Soviet partisans).[46] The exhibition contained images of firing-squads and bodies of young girls, some still children, who had been hung and were dangling from ropes.[48] The group decided to act. It was Fritz Thiel and his wife Hannelore who printed stickers using a child's toy rubber stamp kit.[48] In a campaign initiated by John Graudenz on 17 May 1942, Schulze-Boysen, Marie Terwiel and nineteen others, mostly people from the group around Rittmeister who travelled across five Berlin neighbourhoods to paste the stickers over the original exhibition posters with the message:

- Permanent Exhibition

- The Nazi Paradise

- War, Hunger, Lies, Gestapo

- How much longer?[47]

The Harnacks were dismayed at Schulze-Boysen's actions and decided not to participate in the exploit, believing it to be reckless and unnecessarily dangerous.[49]

On 18 May, Herbert Baum, a Jewish communist who had contact with the Schulze-Boysen group through Walter Husemann, delivered incendiary bombs to the exhibition in the hope of destroying it. Although 11 people were injured, the whole episode was covered up by the government, and the action lead to the arrest of 250 Jews including Baum himself.[48] Following the action, Harnack asked the Kuckoffs to revisit the exhibition to determine whether any damage had been done to it, but they found little damage was visible.[50]

The von Scheliha Group

Rudolf von Scheliha was a cavalry officer, diplomat and later resistance fighter who was recruited by Soviet intelligence while in Warsaw in 1934. Although a member of the Nazi party since 1938, he took an increasingly critical stance against the Nazi regime by 1938 at the latest. He became an informant to journalist Rudolf Herrnstadt[51] Intelligence from von Scheliha would be sent to Herrnstadt, via the cutout Ilse Stöbe,[52] who would then pass it to the Soviet embassy in Warsaw.[53] In September 1939, Scheliha was appointed director of an information department in the Foreign Office, that was created to counter foreign press and radio news by creating propaganda about the German occupation policy in Poland.[54] This necessitated a move back to Berlin, and Stöbe followed, attaining a position arranged by von Scheliha in the press section of the Foreign Office.[55] that enabled her to pass documents from von Scheliha to a representative of TASS.

Von Scheliha's position in the information department exposed him to reports and images of Nazi atrocities, enabling him to verify the veracity of foreign reports of Nazi officials. By 1941, von Scheliha had become increasingly dissatisfied with the Nazi regime and began to resist by collaborating with Henning von Tresckow.[54] Scheliha secretly made a collection of documents on the atrocities of the Gestapo, and in particular, on murders of Jews in Poland, which also contained photographs of newly established extermination camps.[56] He informed his friends first before later attempting to notify the Allies, including a trip to Switzerland with information on Aktion T4 that was shared with Swiss diplomats. His later reports exposed the Final Solution.[57] After Operation Barbarossa severed Soviet lines of communication, Soviet intelligence made attempts to reconnect with Von Scheliha in May 1942, but the effort failed.[58]

Individuals and small groups

Other small groups and individuals, who knew little or nothing about each other, each resisted the National Socialists in their own way until the Gestapo arrested them and treated them as a common espionage organization from 1942 to 1943.

- Kurt Gerstein

- Kurt Gerstein was a German SS officer who had twice been sent to concentration camps in 1938 due to close links with the Confessional Church and had been expelled from the Nazi Party. As a mine manager and industrialist, Gerstein was convinced that he could resist by exerting influence inside the Nazi administration. On 10 March 1941, when he heard about the German euthanasia program Aktion T4, he joined the SS and by chance became Hygiene-Institut der Waffen-SS (Institute for Hygiene of the Waffen-SS) and was ordered by the RSHA to supply prussic acid to the Nazis. Gerstein set about finding methods to dilute the acid, but his main aim was to report the euthanasia programme to his friends. In August 1942, after attending a gassing using a diesel engine exhaust from a car, he informed the Swedish embassy in Berlin of what happened.[59]

- Willy Lehmann

- Willy Lehmann was a communist sympathizer who was recruited by the Soviet NKVD in 1929 and became one of their most valuable agents. In 1932 Lehmann joined the Gestapo and reported to the NKVD the complete work of the Gestapo.[60] In 1935 Lehmann attended a rocket engine ground firing test in Kummersdorf that was attended by Wernher von Braun. From this Lehmann sent six pages of data to Stalin on 17 December 1935.[61] Through Lehmann, Stalin also learned about the power struggles in the Nazi party, rearmament work and even the date of Operation Barbarossa. In October 1942 Lehmann was discovered by the Gestapo and murdered without trial.[60] Lehmann had no connection to the Schulze-Boysen or Harnack group.

Belgium, France and the Low Countries

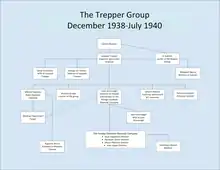

The Trepper Group

Belgium was a favourite place for Soviet espionage to establish operations before World War II as it was geographically close to the centre of Europe, provided good commercial opportunities between Belgium and the rest of Europe and most important of all, the Belgian government was indifferent to foreign espionage operations that were conducted as long as they were against foreign powers and not Belgium itself.[62][63] The first Soviet agents to arrive in Belgium were technicians. The Red Army agent and radio specialist Johann Wenzel arrived in January 1936, [64] to establish a base.

Leopold Trepper was an agent of the Red Army Intelligence and had been working with Soviet intelligence since 1930. [65] Trepper along with Soviet military intelligence officer, Richard Sorge were the two main Soviet agents in Europe and were employed as roving agents setting up espionage networks in Europe and Japan.[66] Whereas Richard Sorge was a penetration agent, Trepper ran a series of clandestine cells for organising agents.[66] Trepper used the latest technology, in the form of small wireless radios to communicate with Soviet intelligence.[66] Although the monitoring of the radios transmissions by the Funkabwehr would eventually lead to the organisations destruction, the sophisticated use of the technology-enabled the organisation to behave as a network.[66]

During the 1930s, Trepper had worked to create a large pool of informal intelligence sources, through contacts with the French Communist Party.[67] In 1936, Trepper became the technical director of Soviet Red Army Intelligence in western Europe.[68] He was responsible for recruiting agents and creating espionage networks.[68] During early 1938, he was sent to Brussels to establish commercial cover for a spy network in France and the Low Countries. In the autumn of 1938, Trepper approached Jewish businessman anf former Comiterm agent Léon Grossvogel, whom he had known in Palestine.[69] Grossvogel ran a small business called Le Roi du Caoutchouc or The Raincoat King on behalf of its owners. Trepper had a plan to use money that had been provided to him, to create an business that would be the export division of The Raincoat King.[70] The new business was given an unidiomatic name of Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company.[69] Trepper's plan was to wait until the company gained market share, and then when it was of sufficient size, infiltrate it with communist personal in positions such shareholders, business managers and department heads.[71] On 6 March 1939, Trepper, now using the alias Adam Mikler, a wealthy Canadian businessman, moved to Brussels with his wife to make it his new base.[72]

In March 1939, Trepper was joined by GRU agent Mikhail Makarov posing as Carlos Alamo,[73] who was to provide expertise in forged documentation e.g. preparation of Kennkartes.[74] However, Grossvogel had recruited Abraham Rajchmann, an criminal forger to the group and thenceforth, Makarov became a radio operator.[75] On the July 1939, Trepper was joined in Brussels by GRU agent Anatoly Gurevich posing as the wealthy Uruguayan Vincente Sierra'[76] Gurevich has already completed his first operation by meeting Schulze-Boysen in order to him as an intelligence source and to arrange a courier service.[76] Gurevich's original remit was to learn the operation of the raincoat company and establish a new store in Copenhagen.[76]

Wartime activity

At the start of the war, Trepper had to revise his plans significantly. After the conquest of Belgium in May 1940, Trepper fled to Paris, leaving Gurevich responsible for the Belgium network.[77] Trepper's assistants in France were Grossvogel and Polish Jew Hillel Katz. In Paris, Trepper contacted General Ivan Susloparov, Soviet Military attaché in the Vichy government,[78] both in an attempt to reconnect with Soviet intelligence and locate another transmitter.[79] After passing his intelligence to Susloparov, Trepper started to organise a new cover company by recruiting businessman Nazarin Drailly. On 19 March 1941, Drailly became the main shareholder in a cover company Simexco, located in Brussels.[80] Trepper also created a similar company in Paris that was known as Simex and was run by former Belgian diplomat Jules Jaspar along French commercial director Alfred Corbin. Both companies sold black market goods to the Germans but their best customer was Organisation Todt, the civil and military engineering organisation of Nazi Germany.

During December 1941, the Funkabwehr discovered Trepper's transmitter in Brussels.[81] Trepper himself was arrested on 5 December 1942 in Paris.[82] The Germans tried to enlist his help as part a sophisticated anti-Soviet operation, to continue transmitting disinformation to Moscow under German control, as part of a playback (German:Funkspiel) operation. According to orders, and relying on training, Trepper agreed to work for the Germans, and began transmitting, which may have included hidden warnings, but saved his life.[83] During September 1943 he escaped and hid with the French Resistance. Operations by the Trepper group had been entirely eliminated by the spring of 1943. Most agents were executed.

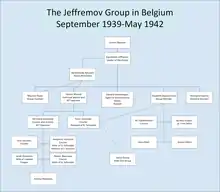

The Jeffremov Group

This network was run by Soviet Army Captain Konstantin Jeffremov. He arrived in Brussels in March 1939 to organise various groups into a network.[84] Jeffremov's group was independent of Trepper's group, although there were some members who worked for both groups. He made contact with radio operator Johann Wenzel and Dutch national and leading Cominterm member Daniël Goulooze.[85] Both the husband and wife couple of Franz Schneider and Germaine Schneider were recruited by Henry Robinson (spy) around the same time. [86] The couple were members of the Communist Party of Belgium and been running Comiterm safe houses in Brussels.[87]

Wenzel had been in Belgium since January 1936 but the Belgian authorities refused him permission to remain, so he moved to the Netherlands in early 1937 where he made contact with Goulooze. At the end of 1938, Wenzel recruited Dutch national and Rote Hilfe member Anton Winterink and later trained him as a radio operator.[85] Winterink worked for Jeffremov for most of 1940 in Brussels but made frequent trips to the Netherlands where he established a network.[88] Later in 1940, Jeffremov ordered Winterink to take charge of the network, that became known as group Hilda.[88]

A meeting was arranged in May 1942, between the two men, in Brussels where Trepper instructed Jeffremov to take over Gurevich's espionage network.[89]

These networks steadily gathered military and industrial intelligence in Occupied Europe, including data on troop deployments, industrial production, raw material availability, aircraft production, and German tank designs. Trepper was also able to get important information through his contacts with important Germans. Posing as a German businessman, he had dinner parties at which he acquired information on the morale and attitudes of German military figures, troop movements, and plans for the Eastern Front.

Switzerland

Rote Drei

The Red Three (German: Rote Drei) was a Soviet espionage network that operated in Switzerland during and after World War II. It was perhaps the most important Soviet espionage network in the war, as they could work relatively undisturbed. The name Rote Drei was a German appellation, based on the number of transmitters or operators serving the network, and is perhaps misleading, as at times there was four, sometimes even five.[90]

The head of the Soviet intelligence service was Maria Josefovna Poliakova, a Soviet 4th Department agent,[91] who first arrived in Switzerland in 1937 to direct operations.[90] The other important leader in the Switzerland group was Ursula Kuczynski, codenamed Sonia, a colonel of the GRU, who has been sent to Switzerland in late 1938, to recruit a new espionage network of agents[92] that would infiltrate Germany.[93] Poliakova passed control to the new director of the Soviet intelligence service in Switzerland, sometimes between 1939 and 1940. The new director was Alexander Radó, codenamed Dora, who held the secret Red Army rank of Major General.[94][95]

Radó formed several intelligence groups in France and Germany, before arriving in Switzerland in late 1936 with his family. In 1936 Radó formed Geopress, a news agency specialising in maps and geographic information as a cover for intelligence work, and after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, the business began to flourish.[96] In 1940, Radó met Alexander Foote, an English Soviet agent, who joined Ursula Kuczynski's network in 1938, and who would become the most important radio operator for Radó's network. In March 1942, Radó made contact with Rudolf Roessler who would become the most important source of information.[90] Roessler was able to provide prompt access to the secrets of the German High Command.[95] This included the pending details of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union and many more, over a period of two years. A 1949 study by MI5 concluded that Roessler was a true mercenary who demanded payments for his reports that ran into thousands of Swiss francs over the course of the war year. This resulted in Dübendorfer being continually short of money, as Soviet intelligence insisted the link be maintained.[97]

Radó established three networks in Switzerland. The three main sources of information, in decreasing importance:

- The first network was run by Rachel Dübendorfer Sissy and who had the most important contacts of the three subgroups. Dübendorfer received intelligence reports from Rudolf Roessler Lucy via the cutout, Christian Schneider. Dübendorfer passed the reports to Radó who passed them to Foote for transmission.[97] Roessler in turn received the information from sources code named Werther, Teddy, Olga, and Anna. It was never discovered who they were.[90] A study by the CIA concluded that the four sources that were forwarding intelligence to Roessler were the Wehrmacht General Hans Oster, Abwehr chief of staff, Hans Bernd Gisevius, the German politician Carl Friedrich Goerdeler and an unknown man named Boelitz. [98]

- The second network was run by the French journalist Georges Blun Long. His sources could not match the production of Lucy's group in quality or quantity, but were nevertheless important.[90]

- The third espionage network was led by Swiss journalist Otto Pünter Pakbo. Pünter's network was considered the least important.[90]

The three principal agents above were chiefly an organisation for producing intelligence for the Soviet Union. But some of the information that was collected for the Rote Drei was sent to the west through a Czech Colonel, Karel Sedláček. In 1935, Sedláček was trained in Prague for a year in 1935, and sent to Switzerland in 1937 by General František Moravec. By 1938, Sedláček was a friend of Major Hans Hausamann who was Director of the unofficial Bureau Ha, a supposed press-cuttings agency, in fact a covert arm of the Swiss Intelligence. Hausamann has been introduced to the Lucy spy ring by Xaver Schnieper a junior officer in the Bureau. It was unknown whether Hausamann was passing information to Lucy, who passed it to Sedláček who forwarded it to London Czechs in exile, or via an intermediary.[90]

Radio messages examined

The radio stations that were known to exist were established at:

- A station built by Geneva radio dealer Edmond Hamel codenamed Eduard and hidden behind a board in his apartment at Route de Florissant 192a in Geneva. Hamel's wife, who acted as an assistant, prepared the encrypted messages. Radó paid the couple 1000 Swiss francs per month.[99]

- A station built in Geneva by Radó's lover, the waitress Marguerite Bolli at Rue Henry Mussard 8. She earned 800 Swiss francs per month.[99]

- The third station was built by Alexander Foote that was hidden insider a typewriter. The transmitter was located in Lausanne at Chemin de Longeraie 2. Red Army Caption Foote was paid 1300 francs per month.[99]

Wilhelm F. Flicke, a cryptanalyst at the Cipher Department of the High Command of the Wehrmacht, worked on the message traffic created by the Swiss group during World War II. Flicke estimated some 5500 messages or about 5 a day for three years were transmitted.[90] The Trepper Report states that between 1941 and 1943, traffic from the three subgroups between 1941 and 1943 consisted of over 2000 militarily important messages, that were sent to the GRU Central office.[100] In September 1993, the CIA Library also undertook an analysis of traffic throughput and estimated that a reasonable number would be around 5000 for the period it was in operation.[90]

Networking

Berliners with foreign representatives

From 1933 to December 1941, the Harnacks had contact with the US Embassy counsellor Donald R. Heath and Martha Dodd, the daughter of the then US Ambassador William Dodd. The Harnacks would often attend receptions at the American embassy as well as parties organised by Martha Dodd, until about 1937.[101] As like-minded people, the group believed that the population would revolt against the Nazis and when it did not, the group became convinced that new avenues were needed to defeat Hitler. From the summer of 1935, Harnack worked on economic espionage for the Soviet Union, and economic espionage for the United States by November 1939. Harnack was convinced that America would play a part in defeating Nazi Germany.[101]

In September 1940, Alexander Mikhailovich Korotkov acting under his codename of Alexander Erdberg, a Soviet intelligence officer who was part of the Soviet Trade Delegation in Berlin, won over Arvid Harnack as a spy for the Soviet Embassy.[102] Harnack had been an informant but in a meeting with Korotkov in the Harnacks' top floor apartment at Woyrschstrasse in Berlin and later in a meeting arranged by Erdberg in the Soviet Embassy to ensure he was not a decoy, he finally convinced Harnack, who was reluctant to agree.[103] Several reasons have been advanced as to why Harnack decided to become a spy, including a need for money, being ideologically driven, and possibly blackmail by Russian intelligence. It was known that Harnack had planned an independent existence for his friends. According to a statement by Erdberg discovered after the war, he thought Harnack was not motived by money nor ideologically driven but that he was specifically building an anti-fascist organisation for Germany as opposed to an espionage network for Russian intelligence. He considered himself a German patriot. [103]

In February 1937, Schulze-Boysen had compiled a short information document about a sabotage enterprise planned in Barcelona by the German Wehrmacht. It was action from "Special Staff W", an organisation established by Luftwaffe general Helmuth Wilberg to study and analyse the tactical lessons learned by the Legion Kondor during the Spanish Civil War.[26] A cousin to Schulze-Boysen, Gisela von Pöllnitz, placed the document in the mailbox of the Soviet Embassy in Bois de Boulogne.[104]

In April 1939, Anatoly Gurevich was ordered to visit Berlin and attempt to revive Schulze-Boysen as a source. He arrived in Berlin on 29 October 1939 and arranged a meeting, first with Kurt Schulze, the radio operator for Ilse Stöbe and then Schulze-Boysen.[105] At the meeting, Schulze-Boysen confirmed there would no attack on the Soviet Union that year, that Germany did not have enough oil to conduct the war fully. [105] Gurevich persuaded Schulze-Boysen to recruit other people as sources. From 26 September 1940, Harnack passed on knowledge received from Schulze-Boysen about the planned attack on the Soviet Union to Korotkov, but not about the open and branched structure of his group of friends.[106] By 1941, Schulze-Boysen had succeeded in creating his own network. In March 1941, Schulze-Boysen informed Korotkov directly about his knowledge of the German attack plans.[107]

Schulze-Boysen employed the following people in his network: his wife, Libertas, who acted as his deputy; Elisabeth and Kurt Schumacher, who were close contacts; Eva-Maria Buch, who worked in the German Institute of Foreign Affairs; Oda Schottmüller and Erika von Brockdorff, who used their houses for radio operations; Kurt Schulze, radio matters; Herbert Engelsing, an informant; Günther Weisenborn, who produced Nazi commissions for Joseph Goebbels,[108] John Graudenz, whose work as a salesman to the Luftwaffe allowed him to visit most airfields[109] Horst Heillman, a Funkabwehr officer and Elfriede Paul, who acted as a cutout for Engelsing.[110]

Harnack employed the following people in his network: Herbert Gollnow, an Abwehr officer; Wolfgang Havemann, a scientist in German Naval Intelligence Service; Adam and Greta Kuckhoff; German industrialist Leo Skrzypczynski; politician Adolf Grimme; and railway worker John Sieg. Tool designer Karl Behrens and Rose Schlösinger, a secretary at the Federal Foreign Office, were couriers to Hans Coppi.[111]

During May 1941, Korotkov had taken delivery of two shortwave radio sets that had been delivered in the Soviet Union embassy diplomatic pouch, in an attempt to make the Berlin group independent.[112] They were handed to Greta Kuckhoff without precise instructions on how to use them, nor in how to maintain contact with the Soviet leadership in case of war.[112] The two radio sets were of different design. The first set had been damaged by Korotkov and had been returned to the Soviet Union for repair, returned and kept by Greta Kuckhoff on 22 June 1941. That other set was battery-powered, with a range of 600 miles that was passed to Coppi on the instruction of Schulze-Boyson at Kurt and Elisabeth Schumacher's apartment. On 26 June 1941, Coppi sent a message:A thousand greetings to all friends.[113] Moscow replied "We have received and read your test message.[113] The substitution of letters for numbers and vice versa is to be done using the permanent number 38745 and the codeword Schraube", and directing them to transmit at a predefined frequency and time.[114] After that, the batteries were too weak to reach Moscow.

In June 1941, the Soviet Embassy was withdrawn from Berlin, and from that point, Schulze-Boysen's information was couriered to Brussels where it was transmitted using Gurevich's network.[110]

In November 1941, another radio set was passed to Coppi at the Eichkamp S-Bahn railway station. It was supplied by Kurt Schulze, who gave Coppi technical instructions on its use.[115] This set was more powerful, being AC powered. Coppi would later accidentally destroy the AC-powered transmitter by connecting it to a DC power socket, destroying the transformer and Vacuum tube.[116] Coppi and the Harnack/Shulze-Boysen resistance groups never received sufficient training from Korotkov. Indeed, when Greta Kuckhoff was trained she concluded that her own technical preparations were "extraordinarily inadequate".[117] Only a few members of the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack Group knew about these radio experiments.

Contact with other groups

_1964%252C_MiNr_1016.jpg.webp)

Since the beginning of the war in 1939, the Berlin group of friends intensified both exchange and cooperation among themselves. They had a desire to connect with organized and non-organized resistance groups from other regions and sections of the population and to explore common possibilities for action.

Both Harro Schulze-Boysen and Arvid Harnack were good friends with lawyer and academic Carl Dietrich von Trotha.[118] Harnack knew Horst von Einsiedel, also a lawyer, since 1934.[119] Schulze-Boysen knew the diplomat and author, Albrecht Haushofer from the Deutsche Hochschule für Politik, where he was holding seminars.[120] In 1940, Trotha and Einsiedel joined the Kreisau Circle, a resistance group that was officially formed with the merging of the intellectual peers of Jurists Helmuth James von Moltke and Peter Yorck von Wartenburg.[121]

Its members included lawyer, Adam von Trott zu Solz, Albrecht Haushofer, industrialist Ernst Borsig, bureaucrat Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, philosopher, Alfred Delp, politician Julius Leber, scientist Carlo Mierendorff and many others.[121] Harnack and Schulze-Boysen had frequent discussion with the group until 1942.[122][123] Harald Poelchau, the prison priest who accompanied the members of the resistance groups who were to be executed, was part of the Kreisau group.[124]

Other members of the German group sought contact with the then largely destroyed underground network of the KPD. In 1939, the machinist Hans Coppi established contact with the resistance group associated with theatre actor and former KPD member Wilhelm Schürmann-Horster, while they were both taking evening classes.[125]

In 1934, John Sieg and Robert Uhrig met Wilhelm Guddorf and sinologist Philipp Schaeffer while imprisoned in Luckau prison in Brandenburg,[126] later making contact with KPD officials when released from concentration camp. Guddorf, on the other hand, held talks with the Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen Group in Hamburg.[38] The lawyer Josef Römer who had contacts with Sieg, Uhrig and Arthur Sodtke[127] had contact with a Munich resistance group through Bavarian politician Viktoria Hösl.[128]

In November 1942, in a meeting organised by Munich artist, Lilo Ramdohr, White Rose resistance group members Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell visited Chemnitz, to meet Falk Harnack, brother to Arvid Harnack.[129] Scholl and Schmorell were looking to contact anti-Nazi resistance groups in Berlin and unite them together as allies with a common aim.[129] Harnack held discussions with his cousins Klaus and Dietrich Bonhoeffer in order to prepare them for a meeting with Hans Scholls.[130] In the spring of 1943, four members of the White Rose met Falk Harnack again in Munich, but received no clear commitment to his cooperation.[131]

Reorganisation

In July and August 1942, the Soviet Main Directorate of State Security (GRU) tried to re-establish contacts with internal German opponents of Hitler. To this end, German communists in exile who had been trained by the GRU as espionage agents were parachuted into Germany.

On the 16 May 1942, Soviet agents Erna Eifler and Wilhelm Fellendorf were parachuted into East Prussia.[132] They were instructed to contact Ilse Stöbe in Berlin. However, they never managed to locate Stöbe and by June 1942 found themselves in Hamburg, a city they knew well. Fellendorf's mother, Katharina Fellendorf, hid the two. Later they moved, and were hidden by Herbert Bittcher[133] In early July, they took shelter with Bernhard Bästlein.[134][135] Eifler's location was leaked by a communist informer to the Gestapo and she was arrested on the 15 October 1942. [132] Fellendorf managed to escape arrest for another two weeks.[132]

On 5 August 1942 Albert Hoessler and Robert Barth parachuted into Gomel,[136][137] reaching Berlin via Warsaw and Posen, a few days before the arrest of Schulze-Boysen.[138] They had been sent to establish a radio link to the GRU for the Schulze-Boysen Group initially from Erika von Brockdorff's apartment and then Oda Schottmüller apartment.[139] They were caught before they could make preliminary contact with Soviet intelligence.[138]

On the 23 October 1942, Heinrich Koenen parachuted into Osterode in East Prussia and made his way to Berlin, to meet his contact Rudolf Herrnstadt.[140] He carried a radio set and a receipt for $6500 dollars that had been signed by Rudolf von Scheliha in 1938. [141] He planned to use it to blackmail von Scheliha, if he had proved recalcitrant in his endeavours. The Gestapo had advanced notice of Kuenen's arrival from a radio intercept message that they had decrypted.[141] On 29 October 1942, Koenen was arrested by a Gestapo official waiting at Stöbe's apartment.[141]

The group around Robert Uhrig and Beppo Römer had more than two hundred members in Berlin and Munich with branches in Leipzig, Hamburg and Mannheim.[142] In February 1942, the group was infiltrated by the Gestapo. By October 1942, the many members of the Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen Group in Hamburg had been arrested.[142] Several members of these groups including Anton Saefkow, Bernhard Bästlein and Franz Jacob, fled from Hamburg to Berlin and began building a new resistance network of illegal cells in the factories of Berlin, that became known as the Saefkow-Jacob-Bästlein Organization.[142]

Persecution by Nazi authorities

Unmasking

The events that led up to the exposure of the Red Orchestra were facilitated by a number of blunders by Soviet intelligence, over several months.[143] The radio transmission that exposed them, was intercepted at 3:58 am on 26 June 1941[144] and was the first of many that were to be intercepted by the Funkabwehr. The message received at the intercept station in Zelenogradsk had the format: Klk from Ptx... Klk from Ptx... Klk from Ptx... 2606. 03. 3032 wds No. 14 qbv.[144] This was followed by thirty-two 5-figure message groups with a morse end of message terminator containing AR 50385 KLK from PTX. (PTX)[145] Up until that point, the Nazi counter-intelligence operation didn't believe that there was a Soviet network operating in Germany and the occupied territories.[146] By September 1941, over 250 messages had been intercepted,[147] but it took several months for them to reduce the suspected area of transmission to within the Belgium area[148] using goniometric triangulation. On 30 November 1941, close range direction-finding teams moved into Brussels and almost immediately found three transmitter signals. Abwehr officer Henry Piepe was ordered to take charge of the investigation around October or November 1941.[149]

Rue des Atrébates

The Abwehr choose a location at 101 Rue des Atrébates, that provided the strongest signal from PTX[150] and on 12 December 1941 2 pm, the house was raided by the Abwehr and Geheime Feldpolizei.[150]

Inside the house was courier Rita Arnould, writing specialist Anton Danilov as well as cipher clerk Sophia Poznańska.[149] The radio transmitter that was still warm. The woman were trying to burn enciphered messages, which were recovered.[82] The radio operator was Anton Danilov.[149] The Germans found a hidden room holding the material and equipment needed to produce forged documents, including blank passports and inks.[82] Rita Arnoulds psychological composure collapsed when she was captured, stating; I'm glad it is all over.[151] While Arnould became an informer, Poznanska committed suicide in Saint-Gilles prison after being tortured.[152] The next day Mikhail Makarov turned up at the house and was arrested.[149] Trepper also visited the house, but his documentation in the form of an Organisation Todt pass was so authentic,[153] that he was released.[149]

In Berlin, the Gestapo was ordered to assist Harry Piepe and they selected Karl Giering to lead the investigation and the Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle.[154][155]

Arnould identified two passports belonging to the aliases of Trepper and Gurevich, his deputy in Belgium. From the scraps of paper recovered, Wilhelm Vauck, principal cryptographer of the Funkabwehr[156] was able to discover the code being used message encipherment was based on a chequerboard cypher with a book key.[152] Arnould, recalled the agents regularly read the same books and was able to identify the name of one as Le miracle du Professeur Wolmar by Guy de Téramond [157] After scouring most of Europe for the correct edition, a copy was found in Paris on 17 May 1942.[157] The Funkabwehr has discovered that of the three hundred intercepts in their possession, only 97 here enciphered using a phrase from the Téramond book. The Funkabwehr never discovered that some of the remaining messages had been enciphered using La femme de trente ans by Honoré de Balzac.[158]

Rue de Namur

Following the arrests, the other two transmitters had remained off the air for six months, except for routine transmission.[158] Trepper assumed the investigation had died down and ordered the transmissions to restart. On 30 July 1942, the Funkabwehr identified a house at 12 Rue de Namur, Brussels and arrested GRU radio operator, Johann Wenzel.[159] Coded messages discovered in the house contained details of such startling content, the plans for Case Blue, that Abwehr officer Henry Piepe immediately drove to Berlin from Brussels to report to German High Command.[160] His actions resulted in the formation of the Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle.[160] Giering ordered Wenzel to be moved to Fort Breendonk where he was tortured and decided to cooperate with the Abwehr, betraying Erna Eifler, Wilhelm Fellendorf, Bernhard Bästlein and the Hübner's.[161]

German counter-intelligence spent months assembling the data[162] but finally Vauck succeeded in decrypting around 200 of the captured messages.[156] On 15 July 1942, Vauck decrypted a message that was dated 10 October 1941.[156] The message was addressed to Kent, (Anatoly Gurevich) and had the lead format:KL3 3 DE RTX 1010-1725 WDS GBD FROM DIREKTOR PERSONAL.[156] When it was decrypted, it gave the location of three addresses in Berlin.[156] The locations were the addresses of the Kuckhoff's, the Harnacks and the Schulze-Boysen's apartments.[162] Another message that had been sent on 28 August 1941 instructed Gurevich to contact Alte, Ilse Stöbe. [163] The three addresses that were passed to the Reich Main Security Office IV 2A who easily identified the people living there, and from 16 July 1942 were put under surveillance.[160]

Germany

The Abwehr's hand was forced when Horst Heilmann attempted to inform Schulze-Boysen of the situation. The previous day Schule-Boysen had asked Heilmann to check if the Abwehr had got wind of his contacts abroad.[164]

Heilmann, a German mathematician. worked at Referat 12 of the Funkabwehr, the radio decryption department in Matthäikirchplatz in Berlin. On 31 August 1942, he discovered the names of his friends in a folder that had been provided to him.[165] According to one version of events Heilmann immediately phoned Schulze-Boysen, using Wilhelm Vauck's office phone as his phone was in use. As Schulze-Boysen wasn't in, Heilmann left a message with the maid of the household. When Schulze-Boysen returned, he immediately phoned the number, but unfortunately, it was answered by Vauck.[166]

On 31 August 1942, Harro Schulze-Boysen was arrested in his office in the Ministry of Aviation. On 7 September 1942, the Harnacks had been arrested while on holiday.[162] Schulze-Boysen's wife, Libertas Schulze-Boysen had received a puzzling phone call from his office several days before.[167] She was also warned by the women who delivered her mail that the Gestapo were monitoring it.[15] Libertas's assistant radio author Alexander Spoerl also noticed that Adam Kuckhoff had gone missing while working in Prague.[167]

Libertas suspected that Schulze-Boysen was arrested, contacted the Engelsing's. Herbert Engelsing tried to contact Kuckhoff without a result.[168] Libertas and Spoerl both started to panic and frantically tried to warn others.[15] They destroyed the darkroom at the Kulurefilm center and Libertas destroyed her meticulously collected archive. At home, she packed a suitcase of all Harro Schulze-Boysens papers and then tried to fabricate evidence of loyalty to the Nazi State by writing fake letters.[168] She sent the suitcase to Günther Weisenborn in the vain hope that it could be hidden and he tried to contact Harro Schulze-Boysen in vain.[168] As the panic reached the rest of the group, frantic searches ensued as each person tried to clear their homes of any anti-Nazi paraphernalia.[168] Documents were burnt, one transmitter was dumped in a river, but the arrests had already started. On 8 September, Libertas was arrested. Adam Kuckhoff was arrested on 12 September 1942 while filming and Greta Kuckhoff the same day.[169] The Coppi's were arrested on the same day[169] along with the Schumacher's and the Graudenz's.[15] By 26 September, Günther Weisenborn and his wife had been arrested.[170] By March 1943, between 120 and 139 people had been arrested (sources vary). [170][171]

Those who were arrested were taken to basement cells (German:Hausgefängnis) in the most dreaded address in all of German-occupied Europe, Gestapo headquarters at 8 Prinze-Albert Strasse (Prince Albert street) and put into protective custody by the Gestapo. [171] The arrests continued and when the cells became overcrowded, several men were sent to Spandau Prison and the women to Alexanderplatz police station.[171] However the leaders remained. Officers of the Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle conducted the initial interrogation[172] At first Harnack, Schulze-Boysen and Kuckhoff refused to say anything,[173] so the interrogators applied intensified interrogations where each was tied between four beds, calf clamps and thumbscrews were applied, then they were whipped.[173]

Belgium

Piepe interrogated Rita Arnould, about the forgers room at Rue des Atrébates.[174] Giering turned to Rita Arnould as the new lead in the investigation and she identified the Abwehr informer and Jewish forger Abraham Rajchmann.[175] It was Rajchmann who forged identity documents in the secret room of 101 Rue des Atrébates. Rajchmann in turn betrayed Soviet agent Konstantin Jeffremov who was arrested on 22 July 1942 in Brussels, while attempting to obtain forged identity documents for himself.[84] Jeffremov was to be tortured but agreed to cooperate and gave up several important members of the espionage network in Belgium and the Netherlands.[176] In the Netherlands, he exposed former Rote Hilfe member and espionage agent Anton Winterink, who was arrested on 26 July 1942 by Piepe.[177] Winterink was taken to Brussels, where he confessed after two weeks of interrogation by torture.[177] Jeffremov (sources vary) also exposed the Simexco company name to the Abwehr and at the same time exposed the name and the existence of the Trepper espionage network in France.[178] Eventually Jeffremov began to work for the Sonderkommando[179] in a Funkspiel operation.[180] Through Jeffremov, contact was made with Germaine Schneider, a courier, [181] who worked for the group between Brussels and Paris.[182] However, Schneider contacted Leopold Trepper, the technical director of a Soviet Red Army Intelligence in western Europe.[183] Trepper advised Schneider to sever all contact with Jeffremov and move to a hideout in Lyons.[179] Giering instead focused on Germaine Schneider's husband Franz Schneider.[179] In November 1942, Franz Schneider was interrogated by Giering but as he was not part of the network he wasn't arrested and managed to inform Trepper that Jeffremov has been arrested.[181]

Abraham Rajchmann was arrested by Piepe on 2 September 1942 when his usefulness as an informer to the Abwehr was at the end.[184] [185] Rajchmann also decided to cooperate with the Abwehr resulting in his betrayal of his mistress, the Comintern member Malvina Gruber, who was arrested on 12 October 1942.[186] Gruber immediately decided to cooperate with the Abwehr, in an attempt to avoid intensified interrogation, i.e. torture. She admitted the existence of Soviet agent Anatoly Gurevich and his probable location, as well as exposing several members of the Trepper espionage network in France.[187]

Following a routine investigation, Harry Piepe discovered that the firm Simexco in Brussels was being used as a cover for Soviet espionage operations by the Trepper network. It was used as a means to generate monies that could be used in day-to-day operations by the espionage group unbeknownst to the employees of the company and at the same time provide travel documentation ([lower-alpha 1]) and facilitates for European wide telephone communication between group members.[188] Piepe was concerned about the large number of telegrams the company was sending to Berlin, Prague and Paris and decided to investigate it. Piepe visited the Chief Commissariat Officer for Brussels, who was responsible for the company. In the meeting, Piepe showed the two photographs that had been discovered at the house at 101 Rue des Atrébates, to the officer who identified them as Trepper and Gurevich.[189]

As part of a combined operation with Giering in Paris, Piepe raided the offices of Simexco on 19 November 1942. When the Gestapo entered the Simexco office they found only one person, a clerk,[190] but managed to discover all the names and addresses of Simexco employees and shareholders from company records.[190] Over the month of November, most of the people associated with the company were arrested and taken to St. Gilles Prison in Brussels or Fort Breendonk in Mechelen.[191] The Nazi German tradition of Sippenhaft, meant than many family members of the accused were also arrested, interrogated and executed.[192]

France

The Abwehr in Brussels and the Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle had full control of the Red Orchestra in Belgium and the Netherlands well before the end of 1942.[193] There is no clear indication when Giering, Piepe and the Sonderkommando moved to Paris, although various sources indicate it was October 1942.[193] Perrault reports it was later summer rather than early autumn.[193] When the unit moved, it relocated to 11 Rue des Saussaies.[193] Before leaving, Piepe and Giering agreed that Rajchmann would be the best person to take to Paris and find Trepper.[193] When the arrived in Paris, Giering sent Rajchmann out to visit all the dead letterboxs that he knew about, while leaving a message to Trepper to contact him.[194] However Trepper never showed up.[194] Giering then tried to establish a meeting with a contact, using information from the correspondence between Simexco and an employee of the Paris office of the Belgian Chamber of Commerce.[194] That ultimately proved unsuccessful, so Giering turned back to investigating Simexco.[194] Giering visited the Seine District Commercial Court where he discovered that Léon Grossvogel was a shareholder of Simex. He had been informed by Jeffremov that Grossvogel was one of Trepper's assistants.[194] Giering and Piepe decided to approach Organisation Todt to determine whether they could provide a way to identify where Trepper was located. Giering obtained a signed certificate of cooperation's from Otto von Stülpnagel, the military commander of occupied France and visited the Todt offices.[194] Giering, together with organisation commander, created a simple ruse to trap Trepper.[195] However, the ruse failed.[196] Giering decided to start arresting employees of Simex. On the 19 November 1942, Suzanne Cointe, a secretary at Simex and Alfred Corbin, the commercial director of the firm were arrested.[197] Corbin was interrogated but failed to disclose the location of Monsieur Gilbert, the alias that Trepper was using in his dealings with the Simex.[198] so Giering sent for a torture expert. However, Corbin's wife told the Abwehr that Corbin had given Trepper the name of a dentist. After being tortured, Corbin informed Giering of the address of Trepper's dentist.[199] Trepper was subsequently arrested on 24 November by Piepe and Giering, while he was sitting in a dentist's chair.[200] It was the result of two years of searching.[201] On the 24 November, Giering contacted Hitler to inform him of the capture of Trepper.[202]

Both Trepper and Gurevich, who had been arrested on the 9 November 1942 in Marseilles[203] were brought to Paris and were treated well by Giering. Trepper informed Giering that his family and relatives in the USSR would be killed if it became known to Soviet intelligence that he was captured.[204] Giering agreed that should Trepper collaborate, his arrest would remain a secret.[204] Over the next few weeks, Trepper betrayed the names of agents to Giering including Léon Grossvogel, Hillel Katz and several other Soviet agents.[204] According to Piepe, when Trepper talked, it was not out of fear of torture or defeat, but out of duty.[205] While he gave up the names and addresses of most of the members of his own network,[206] he was sacrificing his associates to protect the various members of the French Communist Party, whom he had an absolute belief in.[205] Unlike Trepper, Gurevich refused to name any agents he had recruited.[207]

Germany

On the 25 September 1942, Reich Marshal Hermann Göring, Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler and Gestapo Chief Inspector Heinrich Müller meet to discuss the case.[208] They decided the whole network should be charged with espionage and treason together as a group.[208] In the second half of October, Müller proposed that the trial take place at Volksgerichtshof where most sedition cases were directed.[209] Its new president in August 1942 was Roland Freisler[210] who almost always sided with the prosecuting authority, to the point that being brought before him was tantamount to a capital charge.[211][212] Himmler who was a proponent of the proposal, reported it to Hitler. [210] However, the Führer, aware of the military nature of many people in the group, ordered Göring to burn out the cancer.[210] Goring brought Schulze-Boysen into the air ministry, so needed to choose the correct prosecutor.[209] On 17 October 1942, Hermann Göring met with Judge Advocate Manfred Roeder aboard his special train in the town of Vinnytsia.[209] Goering trusted Roeder to prosecute the case correctly, as he was unlikely to sympathise with any humanitarian motives that would be offered by the defendants.[213] It was only because Roeder was designated as prosecuting counsel that Hitler approved Goering's plan and agreed to hold the trial in the Reichskriegsgericht (RKG, Reich Imperial Court) in Berlin, the highest German military court, instead of the Volksgerichtshof.[214] whose judgements he considered insufficiently harsh.[214] Roeder was seconded to the Reich War Prosecutor's Office especially for the proceedings and commissioned Roeder to take on the indictment of the resistance group before the Reich Imperial Court.[214] Roeder had not been a member of the Reich Military Court prior to that point, and his involvement was an expression of the trust that Göring placed in him. [214] Roeder was universally disliked. Rudolf Behse, counsel for the defendants stated that cynicism and brutality were at the core of his character, stating that his limitless ambition was matched only by his innate sadism.[215] Even his colleagues found him harsh and inconsiderable.[215] Prosecuting judge Eugen Schmitt stated that there was something lacking in his temperament; he did not possess the normal man's sympathy for the suffering of others.... When Axel von Harnack visited Roeder on behalf of the Harnacks, he stated of Roeder, Never since have I experienced an impression of brutality as I did from this man. He was a creature surrounded by an aura of fear.[215]

At the beginning of November 1942, the Gestapo investigation delivered 30 volumes of reports[215] to the Reich War Prosecutor's Office for processing by Roeder.[214] Roeder studied the files but found them inadequate, so decided to conduct further short interrogations.[215] By the end of November 1942, a 90-page report was written by Horst Kopkow known as the Bolshevist Hoch Landesverrats that summarised the activities of the group and it was passed to senior members of the Nazi state for review[216] With the production of the report, the Gestapo considered the initial phase of the investigation successful.[216] At the same time, Roeder completed an 800-page indictment and proceeded to prosecute the group.[215] Roeder determined that 76 people would stand trial of the original group.[217] The indictments were broken down in groups.[217]

On the 15 December 1942, the trial began in secret, in the 2nd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht.[218] Five individuals that consisted of a vice-admiral, two generals and two professional judges made up the judicial panel that decided the legal case for each defendant.[218] The presiding judge was Senate President Alexander Kraell.[219]

The trial was a legal travesty. Prisoners were never able to read their indictments and often they would only meet their lawyers minutes before the case started, in trials that often only lasted hours, with the verdict pronounced on the same day.[217] There was no jury, no peers, no German civilians present in the court,[219] only Gestapo spectators. Attempts were made by family members to find suitable lawyers. Falk Harnacks cousin Klaus Bonhoeffer was asked to represent the Harnacks but had refused.[217] In the end, only four lawyers were found to represent the 79 defendants, in over 20 trials. [217] At the centre of the "evidence" prepared by uncontrolled Gestapo interrogations was espionage and subversive activity, which was considered high treason and treason and was punishable by the death penalty.[220] Roeder used the process not only to establish the crimes but also to comprehensively portray the private relationships of the accused in order to show them off as thoroughly depraved immoral people, humiliate them and break them.[217][221]

Germany

In Germany hanging had been outlawed since the 17th Century[222] In March 1933, the Act on the Imposition and Execution of the Death Penalty was enacted that permitted hanging in public as a particularly dishonourable form of execution. Up until that point, death sentences were carried out by firing squad in the military courts and by beheading by the guillotine in civil courts.[222] It was seen as nefarious by the Nazis and at the same time, elicited a feeling of shame by the victims.[222] On 12 December 1942, an order was explicitly sent by Otto Georg Thierack to Plötzensee Prison specifying gallows to hang eight people simultaneously.[222] The notice was sent a full three days before the trial. Hitler wanted to further punish the group and indicated the verdict was already fixed.[222]

The first eleven death sentences for "high and state treason"[223] and two sentences for "passive aiding and abetting in high treason" of six and ten years in prison were issued on 19 December[224] and were presented to Hitler on 21 December. He rejected all requests for pardon[225] revoked the two penal sentences and referred these cases to the 3rd Senate of the RKG to reopen the case. In the eleven death sentences, the method and schedule of the executions were determined. On December 22, from 7:00 p.m. to 7:20 p.m., the following were hanged every four minutes:[226]

From 20:18 to 20:33 o'clock, every three minutes the following were beheaded:[227]

Roeder was present at the executions as chief prosecutor. The prison priest Harald Poelchau, who was otherwise always allowed to accompany the executioner, was not informed this time and only happened to know the execution date on the afternoon of 22 December. After 1945, he wrote the book he last hours. Memories of a prison priest (German:Die letzten Stunden : Erinnerungen eines Gefängnispfarrers).[228]

On 16 January 1943, the 3rd Senate also sentenced Mildred Harnack and Erika von Brockdorff to death on the basis of new incriminating evidence from the Gestapo claiming that the women had knowledge of the radio messages. From 14 to 18 January 1943, the 2nd Senate heard the cases of nine other defendants who had been involved in the adhesive sticking operation. They were all sentenced to death for "favouring the enemy" and "war treason". From 1 to 3 February, six other defendants were tried: Adam and Greta Kuckhoff, Adolf and Maria Grimme, Wilhelm Guddorf and Eva-Maria Buch. Only the death sentence for Adolf Grimme requested by Roeder was reduced to three years imprisonment: Grimme was able to make it credible that he had only seen the Agis leaflet briefly once. His wife was released without condition.[229]

Of the remaining prisoners, 76 were sentenced to death, 13 of them by the People's Court; the remaining 50 were sentenced to prison. Four men among the accused committed suicide in prison, five were murdered without trial.[230] Some 65 death sentences were carried out.[231]

Reception after the war

German contemporary witnesses

In the first post-war years, the performance and role model of the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group were unreservedly recognized as an important part of the German resistance against the Nazis. In his book Offiziere gegen Hitler (Officers against Hitler) (1946) on the assassination attempt of 20 July 1944 plot, resistance fighter and later writer Fabian von Schlabrendorff paid tribute to the Germans executed as members of the Red Orchestra.[232]

In 1946, the German historian and author, Ricarda Huch publicly called for contributions to her planned collection of biographies of executed resistance fighters Für die Märtyrer der Freiheit (For the Martyrs of Freedom).[233]

Huch explained the task as

- How we need the air to breath, light to see, so we need noble people to live... When we commemorate those who lost their lives in the struggle against National Socialism, we fulfill a duty of gratitude, but at the same time we do ourselves good, because by commemorating them we rise above our Bad luck.[233]