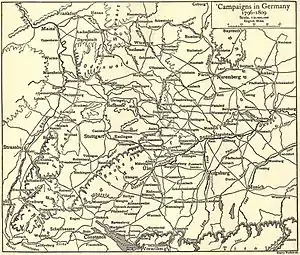

Rhine campaign of 1796

In the Rhine campaign of 1796 (June 1796 to February 1797), two First Coalition armies under the overall command of Archduke Charles outmaneuvered and defeated two French Republican armies. This was the last campaign of the War of the First Coalition, part of the French Revolutionary Wars.

| Rhine campaign of 1796 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

Taking one of the redoubts of Kehl by throwing rocks, 24 June 1796, Frédéric Regamey | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Army of the Lower Rhine Army of the Upper Rhine |

Army of Sambre and Meuse Army of the Rhine and Moselle | ||||||

The French military strategy against Austria called for a three-pronged invasion to surround Vienna, ideally capturing the city and forcing the Holy Roman Emperor to surrender and accept French Revolutionary territorial integrity. The French assembled the Army of Sambre and Meuse commanded by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan against the Austrian Army of the Lower Rhine in the north. The Army of the Rhine and Moselle, led by Jean Victor Marie Moreau, opposed the Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine in the south. A third army, the Army of Italy, commanded by Napoleon Bonaparte, approached Vienna through northern Italy.

The early success of the Army of Italy initially forced the Coalition commander, Archduke Charles, to transfer 25,000 men commanded by Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser to northern Italy. This weakened the Coalition force along the 340-kilometer (211-mile) front stretching along the Rhine from Basel to the North Sea. Later, a feint by Jourdan's Army of Sambre and Meuse convinced Charles to shift troops to the north, allowing Moreau to cross the Rhine at the Battle of Kehl on 24 June and defeated the Archduke's Imperial contingents. Both French armies penetrated deep into eastern and southern Germany by late July, forcing the southern states of the Holy Roman Empire into punitive armistices. By August, the French armies had extended their fronts too thinly and rivalry among the French generals complicated cooperation between the two armies. Because the two French armies operated independently, Charles was able to leave Maximilian Anton Karl, Count Baillet de Latour with a weaker army in front of Moreau on the southernmost flank and move many reinforcements to the army of Wilhelm von Wartensleben in the north.

At the Battle of Amberg on 24 August and the Battle of Würzburg on 3 September, Charles defeated Jourdan's northern army and compelled the French army to retreat, eventually to the west bank of the Rhine. With Jourdan neutralized and retreating into France, Charles left Franz von Werneck to watch the Army of Sambre and Meuse, making sure it did not try to recover a foothold on the east bank of the Rhine. After securing the Rhine crossings at Bruchsal and Kehl, Charles forced Moreau to retreat south. During the winter the Austrians reduced the French bridgeheads in the sieges of Kehl and the Hüningen, and forced Moreau's army back to France. Despite Charles' success in the Rhineland, Austria lost the war in Italy, against Napoleon Bonaparte, which resulted in the Peace of Campo Formio.

Background

The rulers of Europe initially viewed the French Revolution as an internal dispute between the French king Louis XVI and his subjects. As revolutionary rhetoric grew more strident, the monarchs of Europe declared their interests as one with those of Louis and his family. The Declaration of Pillnitz (27 August 1791) threatened ambiguous, but quite serious, consequences if anything should happen to the French royal family. French émigrés, who had the support of the Habsburgs, the Prussians, and the British, continued to agitate for a counter-revolution.[1]

Finally, on 20 April 1792, the French National Convention declared war on the Habsburg Monarchy, pushing all of the Holy Roman Empire into war. Consequently, in this War of the First Coalition (1792–98), France ranged itself against most of the European states sharing land or water borders with her, plus Great Britain, the Kingdom of Portugal and the Ottoman Empire.[1]

From 1793 to 1795, French successes varied. By 1794, the armies of the French Republic were in a state of disruption. The most radical of the revolutionaries purged the military of all men conceivably loyal to the Ancien Régime. The levée en masse created a new army with thousands of illiterate, untrained men placed under the command of officers whose principal qualifications may have been their loyalty to the Revolution instead their military acumen.[2] Traditional military organization was disrupted by the formation of the new demi-brigade, units created by the amalgamation of old military units with new revolutionary formations: each demi-brigade included one unit of the old royalist army and two from the new mass conscription. The losses of this revolutionized army in the Rhine Campaign of 1795 disappointed the French public and the French government.[1]

Furthermore, by 1795, the army had already made itself odious throughout France, by both rumor and action, through its rapacious dependence upon the countryside for material support and its general lawlessness and undisciplined behavior. After April 1796, the military was paid in metallic rather than worthless paper currency, but pay was still well in arrears. The French Directory believed that war should pay for itself and did not budget to pay, feed, and equip its troops.[3] Thus, a campaign that would take the army out of France became increasingly urgent for both budgetary and internal security reasons.[1]

Political terrain

The predominantly German-speaking states on the east bank of the Rhine were part of the vast complex of territories in central Europe called the Holy Roman Empire, of which the Archduchy of Austria was a principal polity and its archduke typically the Holy Roman Emperor. The French government considered the Holy Roman Empire as its principal continental enemy.[4] The territories in the Empire of late 1796 included more than 1,000 entities, including Breisgau (Habsburg), Offenburg and Rottweil (free cities), the territories belonging to the princely families of Fürstenberg and Hohenzollern, the Duchy of Baden, the Duchy of Württemberg, and several dozen ecclesiastic polities. Many of these territories were not contiguous: a village could belong predominantly to one polity, but have a farmstead, a house, or even one or two strips of land that belonged to another polity. The size and influence of the polities varied, from the Kleinstaaterei, the little states that covered no more than a few square miles, or included several non-contiguous pieces, to such sizable, well-defined territories as Bavaria and Prussia.[5]

The governance of these states also varied: they included the autonomous free Imperial cities (also of different sizes and influence), ecclesiastical territories, and dynastic states such as Württemberg. Through the organization of Imperial Circles, also called Reichskreise, groups of states consolidated resources and promoted regional and organizational interests, including economic cooperation and military protection. Without the participation of such principal states of the Empire as the Archduchy of Austria, Prussia, the Electorate of Saxony, and Bavaria, for example, these small states were vulnerable to invasion and conquest because they were unable to defend themselves on their own.[5][Note 1]

Geography

The Rhine formed the boundary between the German states of the Holy Roman Empire and its neighbors. Any attack by either party required control of the crossings. The river began in the Swiss canton of Graubünden (also called the Grisons) near Lake Toma and flowed along the Alpine region bordered by Liechtenstein, northward into Lake Constance, where it traversed the lake. From Lake Constance, the river left the lake at Stein am Rhein and flowed westerly along the border between the German states and the Swiss cantons. The c. 150-kilometer (93 mi) stretch between Stein am Rhein and Basel, called the High Rhine, cut through steep hillsides only near the Rhine Falls and flowed over a gravel bed; in such places as the former rapids at Laufenburg, or after the confluence with the even larger Aare below Koblenz, Switzerland it moved in torrents.[6]

At Basel, where the terrain flattened, the Rhine made a wide, northerly turn at the Rhine knee, and entered what the locals call the Rhine Ditch (Rheingraben). This formed part of a rift valley some 31 km (19 mi) wide bordered by the mountainous Black Forest on the east (German side) and the Vosges mountains on the west (French side). At the far edges of the eastern flood plain, tributaries cut deep defiles into the western slope of the mountains;[7] this became especially important in the rainy autumn of 1796. Further to the north, the river became deeper and faster, until it widened into a delta, where it emptied into the North Sea.[8] In the 1790s, this part of the river was wild and unpredictable and armies crossed at their peril. River channels wound through marsh and meadow, and created islands of trees and vegetation that were periodically submerged by floods. Flash floods originating in the mountains could submerge farms and fields. Any army wishing to traverse the river had to cross at specific points: in 1790, systems of viaducts and causeways made access across the river reliable, but only at Kehl, by Strasburg, at Hüningen, by Basel, and in the north by Mannheim. Sometimes, crossing could be executed at Neuf-Brisach, between Kehl and Hüningen, but the small bridgehead made this unreliable.[9][Note 2] Only to the north of Kaiserslauten did the river acquire a defined bank where fortified bridges offered reliable crossing points.[11]

War plans

At the end of the Rhine Campaign of 1795 the two sides had called a truce,[12] but both sides continued to plan for war. In a decree on 6 January 1796, Lazare Carnot, one of the five French Directors, gave Germany priority over Italy as a theater of war. The French First Republic's finances were in poor shape so its armies would be expected to invade new territories and then live off the conquered lands.[13] Knowing that the French planned to invade Germany, on 20 May 1796 the Austrians announced that the truce would end on 31 May, and prepared for invasion.[14]

Habsburg and Imperial organization

Initially, the Habsburg and Imperial troops numbered about 125,000, including three autonomous corps, of which 90,000 were commanded by the 25-year-old Archduke Charles, brother of the Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II.[15] Before the campaign in the Rhineland started, Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser took 25,000 of these as reinforcements to Italy after news arrived of Bonaparte's early successes. In the new situation, the Aulic Council, the Emperor's war advisors, gave Charles command over Austrian forces that had been transferred from the border provinces, and over the Imperial contingents (Kreistruppen) of the Holy Roman Empire.[16] The Austrian strategy was to capture Trier and to use this position on the west bank to strike at each of the French armies in turn; failing that, the Archduke was to hold his ground.[12]

The 20,000-man right (north) wing under Duke Ferdinand Frederick Augustus of Württemberg stood on the east bank of the Rhine behind the river Sieg ("Fortune"), observing the French bridgehead at Düsseldorf. A portion patrolled the west bank and behind the river Nahe. The Mainz Fortress and Ehrenbreitstein Fortress garrisons totaled about 10,000 more, including 2,600 at Ehrenbreitstein. Charles concentrated the bulk of his force, commanded by one of his more experienced generals, Count Baillet Latour, between Karlsruhe and Darmstadt, where the confluence of the Rhine and the Main made an attack most likely; the rivers offered a gateway into eastern German states and ultimately to Vienna, with good bridges crossing a relatively well-defined river bank. A force occupied Kaiserslautern on the west bank. Wilhelm von Wartensleben's autonomous corps covered the line between Mainz and Giessen.[Note 3][18]

The far left wing, under Anton Sztáray, Michael von Fröhlich and Louis Joseph, Prince of Condé, guarded the Rhine border from Mannheim to Switzerland. This part of the army included the conscripts drafted from the Imperial Circles. Charles did not like to use the militias in any vital location and once it seemed clear to him that the French intended to cross at the middle Rhine, the Archduke felt no qualms placing his militia men at Kehl.[19] In Spring 1796, when resumption of war appeared imminent, the 88 members of the Swabian Circle, which included most of the states (ecclesiastical, secular, and dynastic) in Upper Swabia, had raised a small force of about 7,000 men. These were field hands, the occasional journeyman, and day laborers drafted for service, but untrained in military matters. The remainder of the force included experienced troops from the Habsburg frontier troops stationed just north of Rastatt, and a cadre of French royalists and a couple of hundred mercenaries at Freiburg im Breisgau.[20]

Compared to French, Charles had half the number of troops covering a 340-kilometer (340,000 m) front that stretched from Switzerland to the North Sea in what Gunther Rothenberg called the "thin white line".[Note 4] Imperial troops could not cover the territory from Basel to Frankfurt with sufficient depth to resist the pressure of their opponents.[15]

French organization

Lazare Carnot's grand plan called for the two French armies along the Rhine to press against the Austrian flanks. These armies were to be commanded by two of their most experienced generals, Jean-Baptiste Jourdan and Jean Victor Moreau, who led (respectively) the Army of Sambre and Meuse and the Army of the Rhine and Moselle at the outset of the 1796 campaign.[21]

Moreau's army was positioned east of the Rhine at Hüningen and to the north, its center along the river Queich near Landau and its left wing extended west toward Saarbrücken.[16][Note 5] The Army of Rhine and Moselle numbered 71,581 foot soldiers and 6,515 cavalry, excluding gunners and sappers.[22] The 80,000-man Army of Sambre and Meuse already held the west bank of the Rhine as far south as the Nahe and then southwest to Sankt Wendel. On the army's left (northern) flank, Jean Baptiste Kléber had 22,000 troops in a bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Rhine in an entrenched camp at Düsseldorf. Kléber was to push south from Düsseldorf, while Jourdan's main force would besiege Mainz and then cross the Rhine into Franconia. It was hoped that this advance would induce the Austrians to withdraw all of their forces from the Rhine's west bank to face the French onslaught.[21] While Jourdan's actions near Düsseldorf drew Austrian attention northward, Jean Victor Marie Moreau was to lead the Army of Rhine and Moselle across the Rhine at Neuf-Breisach, Kehl and Hüningen, invade the Duchy of Baden, besiege or take Mannheim, and subdue Swabia and the Duchy of Bavaria. Ultimately, Moreau was to converge on Vienna; Jourdan, who by mid-summer theoretically should have taken most of Franconia, would veer south to provide a rearguard for Moreau's advance on the Habsburg capital.[21]

Simultaneously, Napoleon Bonaparte was to invade Italy, neutralize the Kingdom of Sardinia and seize Lombardy from the Austrians. The Army of Italy was instructed to cross the Alps via the Tyrol and join the other French armies in crushing the Austrian forces in southern Germany. By the spring of 1796, Jourdan and Moreau each had 70,000 men while Bonaparte's army numbered 63,000, including reserves and garrisons. François Christophe de Kellermann also counted 20,000 troops in the Army of the Alps holding the area between Moreau and Bonaparte on the western side of modern Switzerland; there was a smaller army in southern France that played no role in the Rhine Campaign.[23]

Operations

Crossing the Rhine

According to plan, Kléber made the first move, advancing south from Düsseldorf against Württemberg's wing of the Army of the Lower Rhine.[16] On 1 June 1796, a division of Kléber's troops led by François Joseph Lefebvre seized a bridge over the Sieg from Michael von Kienmayer's Austrians at Siegburg. Meanwhile, a second French division under Claude-Sylvestre Colaud menaced the Austrian left flank.[24] Württemberg retreated south to Uckerath but then fell further back to a well-fortified position at Altenkirchen. On 4 June, Kléber defeated Württemberg in the Battle of Altenkirchen, capturing 1,500 Austrian soldiers, 12 artillery pieces and four colors. Charles withdrew the Austrian forces from the Rhine's west bank and gave the Army of the Upper Rhine the principal responsibility to defend Mainz.[25] After this setback, Charles replaced Württemberg with Wartensleben, much to Württemberg's annoyance: the Duke returned to Vienna and offered the Aulic Council his persistent criticism of Charles' decisions and advice on how they could run the war better from the capital.[26] Jourdan's main body crossed the Rhine on 10 June at Neuwied to join Kléber[16] and the Army of Sambre and Meuse advanced to the river Lahn.[27]

Leaving 12,000 troops to guard Mannheim, Charles repositioned his troops among his two armies and swiftly moved north against Jourdan. The Archduke defeated the Army of Sambre and Meuse at the Battle of Wetzlar on 15 June 1796 and Jourdan lost no time in recrossing to the safety of the west shore of the Rhine at Neuwied.[27] Following up, the Austrians clashed with Kléber's divisions at Uckerath, inflicting 3,000 casualties on the French for a loss of only 600. After his success, Charles left 35,000 men with Wartensleben, 30,000 more in Mainz and the other fortresses and moved south with 20,000 troops to help Latour. Kléber withdrew into the Düsseldorf defenses.[28]

The action was not an unmitigated success for the Coalition. While Charles was inflicting damage at Wetzlar and Uckerath, on 15 June, Desaix's 30,000-man command mauled Franz Petrasch's 11,000 Austrians at Maudach. The French lost 600 casualties while the Austrians suffered three times as many.[29] After feinting at the Austrian positions near Mannheim, Moreau sent his army south from Speyer on a forced march to Strasburg; Desaix, leading the advanced guard, crossed the Rhine at Kehl near Strasburg on the night of 23/24 June.[27]

The Coalition's position at Kehl was modestly defended. On 24 June Louis Desaix's advance group attacked the out-classed Swabian farmhands there on the bridge, preceding the main force of 27,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry.[29] In the First Battle of Kehl the 10,065 French troops involved in the initial assault lost only 150 casualties. The Swabians were outnumbered and could not be reinforced. Most of the Imperial Army of the Rhine had remained near Mannheim, where Charles anticipated the principal attack. Neither the Condé's troops in Freiburg im Breisgau nor Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg's force in Rastatt could reach Kehl in time to support them. The Swabians suffered 700 casualties and lost 14 guns and 22 ammunition wagons.[29] Moreau reinforced his newly won bridgehead on 26–27 June so that he had 30,000 troops to oppose only 18,000 locally based Coalition troops. Leaving Delaborde's division on the west bank to watch the Rhine between Neuf-Brisach and Hüningen, Moreau moved to the north against Latour. Separated from their commander, the Austrian left flank under Fröhlich and the Condé withdrew to the southeast.[27] At Renchen on 28 June, Desaix caught up with Sztáray's column of 9,000 Austrian and Reichsarmee (Imperial) troops. For only 200 of their own casualties, the French inflicted losses of 550 killed and wounded, while capturing 850 men, seven guns and two ammunition wagons.[30]

Furthermore, at Hüningen, near Basel, on the same day that Moreau's advance guard crossed at Kehl, Pierre Marie Barthélemy Ferino executed a full crossing, and advanced unopposed east along the German shore of the Rhine, with the 16th and 50th Demi-brigades, the 68th, 50th and 68th line infantry, and six squadrons of cavalry that included the 3rd and 7th Hussars and the 10th Dragoons.[31][Note 6] This gave the French the desired pincer effect, the Army of the Sambre and Meuse approaching from the north, the bulk of the Army of the Rhine and Moselle crossing in the center, and Ferino crossing in the south.[33]

Within a day, Moreau had four divisions across the river, representing a fundamental success of the French plan, and they executed their plan with alacrity. From the south, Ferino pursued Fröhlich and the Condé in a wide sweep east-north-east toward Villingen while Gouvion Saint-Cyr chased the Kreistruppen into Rastatt. Latour and Sztáray tried to hold the line of the river Murg. The French employed 19,000 foot soldiers and 1,500 horsemen in the divisions of Alexandre Camille Taponier and François Antoine Louis Bourcier. The Austrian brought 6,000 men into action under the command of Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg and Johann Mészáros von Szoboszló. The French captured 200 Austrians and three field pieces.[34] On 5 July 1796, Desaix defeated Latour at the Battle of Rastatt by turning both his flanks, and drove his Imperial and Habsburg combined force back to the river Alb. The Habsburg and Imperial armies did not have enough troops to hold off the Army of the Rhine and Moselle and would need reinforcements from Charles, who was occupied in the north keeping Jourdan pinned down on the west bank of the Rhine.[35]

| Date Location | French | Coalition | Victor | Operation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 June Altenkirchen |

11,000 | 6,500 | French | The forces of the Coalition withdrew over the Lahn, to the southeast. French losses were light; Austrians lost 2 battalions and 10 guns. | ||||||

| 9 June 1796 Blockades |

5,700 (approx) | 10,000 | Coalition | The fortifications at Mainz and Ehrenbreitstein provided an important stronghold at the confluence of the rivers Main and Rhine, and the rivers Rhine and Moselle. The blockades at Ehrenbreitstein started on 9 June, and at Mainz on 14 June. | ||||||

| 15 June Maudach |

27,000 infantry 3,000 cavalry |

11,000 | French | The opening action on the Upper Rhine, north of Kehl. Moreau and Jourdan coordinated feinting actions to convince Charles that the principal attack would be between the confluence of Rhine, Moselle, and Mainz, and further north. The Coalition force lost 10% of its members, missing, killed, or wounded. | ||||||

| 15 June Wetzlar and Uckerath |

11,000 | 36,000 not all engaged |

Coalition | After the early clashes the French withdrew, splitting their force. Jourdan moved westward to secure the bridgehead at Neuwied on the Rhine and Kleber moved to the entrenched camp at Düsseldorf, further north. Charles followed, drawing some of his strength from the force between Strasburg and Speyer. | ||||||

| 23–24 June Kehl |

10,000 | 7,000 | French | After feinting to the north, Moreau's advance guard, 10,000 strong, preceded the main force of 27,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry directed at the 6,500–7,000 Swabian pickets on the bridge.[29] Most of the Imperial Army of the Rhine was stationed further north, by Mannheim, where the river was easier to cross, but too far to support the smaller force at Kehl. The Condé's troops were at Freiburg, but still too long a march to relieve them. Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg's force in Rastatt could also not reach Kehl in time.[36] The Swabians were hopelessly outnumbered and could not be reinforced. Within a day, Moreau had four divisions across the river at Kehl. Unceremoniously thrust out of Kehl—there was a rumor they actually had fled at the approach of the French—the Swabian contingent reformed at Rastatt by 5 July. There they managed to hold the city until reinforcements arrived, although Charles could not move much of his army away from Mannheim or Karlsruhe, where the French had also formed across the river.[37] | ||||||

| 28 June Renchen |

20,000 | 6,000 | French | Moreau' troops clashed with elements of a Habsburg Austrian army under Maximilian Anton Karl, Count Baillet de Latour which were defending the line of the river Murg. Leading a wing of Moreau's army, Louis Desaix attacked the Austrians and drove them back to the river Alb.[38] | ||||||

| 21 July Neuwied |

unknown force | 8,000 | French | Jourdan's southernmost flank encountered Imperial and Hessian troops | ||||||

| 4 July Rastatt |

19,000 infantry 1,500 cavalry |

6,000 | French | Principally involved the turning of the Austrian wings. | ||||||

| 8 July Giessen |

20,000 | 4,500 | French | The French surprised a weak Austrian garrison and captured the town. | ||||||

| All troop counts and operational objectives, unless otherwise noted, from Smith pp. 111–132. | ||||||||||

French offensive

Recognizing the need for reinforcements, and fearing his army would be flanked by Moreau's surprise crossings at Kehl and Hüningen, Charles arrived near Rastatt with more troops and prepared to advance against Moreau on 10 July. The French surprised him by attacking first, on 9 July. Despite the surprise, in the Battle of Ettlingen, Charles repulsed Desaix's attacks on his right flank, but Saint-Cyr and Taponier gained ground in the hills to the east of the town, and threatened his flank. Moreau lost 2,400 out of 36,000 men while Charles had 2,600 hors de combat out of 32,000 troops. Anxious about the security of his supply lines, though, Charles began a measured and careful retreat to the east.[39]

French successes continued. With Charles absent from the north, Jourdan recrossed the Rhine and drove Wartensleben behind the Lahn. Pushing forward again, the Army of Sambre and Meuse defeated its opponents in the Battle of Friedberg (also called the First Battle of Limburg) on 10 July, while Charles was busy at Ettlingen.[40] In this action, the Austrians suffered 1,000 casualties against a French loss of 700.[41] Jourdan captured Frankfurt am Main on 16 July. Leaving behind François Séverin Marceau-Desgraviers with 28,000 troops to blockade Mainz and Ehrenbreitstein, Jourdan pressed up the river Main. Following Carnot's strategy, the French commander continually operated against Wartensleben's north flank, causing the Austrian general to fall back.[40] Jourdan's army numbered 46,197 men while Wartensleben counted 36,284 troops; Wartensleben felt no security in attacking the larger French force, and continued to withdraw to the northeast, further away from Charles' flank.[42] Buoyed up by their forward movement and by the capture of Austrian supplies, the French captured Würzburg on 4 August. Three days later, the Army of Sambre and Meuse, under the temporary direction of Kléber, won another clash with Wartensleben at Forchheim on 7 August.[40]

Meanwhile, in the south the Army of Rhine and Moselle continually clashed with Charles' retreating army at Cannstadt near Stuttgart on 21 July 1796.[41] The Swabians and Electorate of Bavaria began to negotiate with Moreau for relief; by mid-July, Moreau's army had control of most of southwestern Germany, and had most of the southwestern states in a punitive armistice. The Imperial troops (Kreistruppen) took little part in the remainder of the campaign and they were disarmed forcibly by Fröhlich, their commander, on 29 July at Biberach an der Riss before they disbanded and returned to their homes.[43] Charles retreated with the Habsburg troops through Geislingen an der Steige around 2 August and was in Nördlingen by 10 August. At this date, Moreau had 45,000 men spread out on a 40 km (25 mi) front centered on Neresheim, but with both flanks unsecured. Meanwhile, Ferino's right wing was out of touch far to the south at Memmingen. Charles planned to cross to the south bank of the Danube, but Moreau was close enough to interfere with the operation. The Archduke decided to launch an attack instead.[44]

| Date Location | French | Coalition | Victor | Operation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 July Giessen |

20,000 | 4,500 | French | The French surprised a weak Austrian garrison and captured the town. | ||||||

| 9 July Ettlingen (or Malsch) |

36,000 | 32,000 | French | Moreau accompanied Desaix's Left Wing with the divisions of infantry, cavalry and horse artillery.[45] The village of Malsch was captured twice by the French and recaptured each time by the Austrians.[35] Latour tried to force his way around the French left with cavalry but was checked by the mounted troops of the Reserve.[46] Finding his horsemen outnumbered near Ötigheim, Latour used his artillery to keep the French cavalry at bay.[35] In the Rhine plain the combat raged until 10 PM.[46] The French wing commander ordered the troops not to press home their assault, but to retreat every time they came against strong resistance. Each attack was pushed farther up the ridge before receding into the valley. When the fifth assault in regimental strength gave way, the defenders finally reacted, sweeping down the slope to cut off the French. Massed grenadier companies to attack one Austrian flank, other reserves bored in on the other flank and the center counterattacked.[47] The French troops that struck the Austrian right were hidden in the nearby town of Herrenalb.[46] As the Austrians gave way, the French followed them up the ridge right into their positions. Nevertheless, Kaim's men laid down such a heavy fire that Lecourbe's grenadiers were thrown into disorder and their leader nearly captured.[47] | ||||||

| 10 July Friedberg |

30,000 | 6,000 | French | After hearing of Moreau's successful assault on Kehl, and crossing the river, Jourdan recrossed the Rhine, attacked Wartensleben's force, and pushed him south to the river Main. | ||||||

| 21 July Cannstatt |

unknown | 8,000 | French | Moreau's force attacked Charles' rearguard. | ||||||

| All troop counts and operational objectives, unless otherwise noted, from Smith pp. 111–132. | ||||||||||

Stasis

At this point in the campaign, either side could have crushed the other by joining their two armies. Wartensleben's recalcitrance frustrated Charles; Wartensleben was an old soldier, a veteran of the Seven Years' War and himself a scion of nobility who saw no need to bend to the wishes of a 25-year-old general, even if that general was an archduke, a brother to the Holy Roman Emperor, and his commander-in-chief. Wartensleben simply ignored instructions or requests from Charles to unite their flanks so that together they could turn and face the French with a united front, and he continued to withdraw further to the northeast, away from the commander-in-chief.[44]

Moreau and Jourdan faced similar difficulties. Jourdan continued in his single-minded pursuit of Wartensleben; Moreau continued his single-minded pursuit of Charles, penetrating deep into Bavaria. The French armies drew further and further away from the Rhine, and from each other, stretching their supply lines and decreasing the possibility of covering each other's flanks. Napoleon later wrote of Moreau's actions, "One would have said that he was ignorant that a French army existed on his left".[40] The historian Theodore Ayrault Dodge asserted that the combined army "could have crushed the Austrians".[44]

| Date Location | French | Coalition | Victor | Operation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 August Neresheim |

47,000 | 43,000 | French | At Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz, Charles brushed aside one of Jourdan's divisions under Major General Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte.[48] This movement placed the Archduke squarely on the French right rear and convinced Wartensleben to turn his force around to join Charles. After the battle, Charles withdrew his troops further east, pulling Moreau further away from Jourdan's flank, thus weakening the French front. After enticing Moreau away from any possible support of Jourdan's Army of the Sambre and Meuse, Charles marched north with 27,000 troops to join with Wartensleben on 24 August; their combined force defeated Jourdan at Amberg and further split the French fronts, Jourdan to the north and Moreau to the south. With his more compact line, Charles held a strategically and tactically superior position.[48] | ||||||

| 17 August Sulzbach |

25,000 | 8,000 | French | At Sulzbach, a small village 45 km (28 mi) east of Nuremberg, Jean-Baptiste Kléber led a portion of the Army of the Sambre and Meuse against Lieutenant Field Marshal Paul von Kray. Of the Austrian force, 900 were killed and wounded and 200 captured. | ||||||

| 22 August Theiningen |

9,000 | 28,000[49] | Tactical Draw[50] | General Bernadotte commanded a division of the Army of the Sambre and Meuse and was tasked with defending the right flank of the army. General Jacques Philippe Bonnaud was to join Bernadotte with another division but due to miscommunication and poor roads, Bonnaud failed to join Bernadotte's division which became isolated.[51] Archduke Charles learned of the isolated French forces and moved toward Newmarkt with 28,000 troops to destroy the French and gain access to Jourdan's line of retreat. However, at Theiningen the French made a stand on favorable ground, and despite being outnumbered three-to-one, repulsed multiple Austrian attacks, a counter-attack, led by Bernadotte himself ended the battle as night fell with neither force yielding the field.[52] The following day Bernadotte conducted a fighting retreat northeast pursued by the Austrians, however, Bernadotte had prevented Charles from cutting Jourdan off from the Rhine. Charles also shifted his lines of supply further north, so his supplies were coming from Bohemia instead of from further south.[53] | ||||||

| 24 August Amberg |

40,000 | 2,500 | Coalition | Charles struck the French right flank while Wartensleben attacked frontally. The French Army of the Sambre and Meuse was overcome by weight of numbers and Jourdan retired northwest. The Austrians lost only 400 casualties of the 40,000 men they brought onto the field. French losses were 1,200 killed and wounded, plus 800 captured out of 34,000 engaged. | ||||||

| 24 August Friedberg |

59,000 | 35,500 | French | On the same day as the battle at Amberg, the French army, which was advancing eastward on the south side of the Danube, managed to catch an isolated Austrian infantry unit, Schröder Infantry Regiment Nr. 7, and the French Army of Condé. In the ensuing clash, the Austrians and Royalists were cut to pieces. Despite Charles' instructions to withdraw northward toward Ingolstadt, Maximilian Anton Karl, Count Baillet de Latour retreated eastward to protect the borders of Austria. This gave Moreau a chance to place his army between the two Austrian forces (Wartensleben's and Charles'), but he did not seize this chance.[54] | ||||||

| 1 September Geissenfeld |

unknown French force from Army of Rhine & Moselle | about 6,000 | French | Major General Nauendorf and Latour led portions of the Army of the Rhine against the French Army of the Rhine & Moselle. Latour withdrew east; Nauendorf remained in Abensberg to cover the Austrian rear. This is the point at which Moreau realized how exposed his force was, and started his withdrawal westwards toward Ulm. | ||||||

| All troop counts and operational objectives, unless otherwise noted, from Smith pp. 111–132. | ||||||||||

Habsburg counteroffensive

The Battle of Neresheim on 11 August marked the turning point; it was a series of clashes fought on a broad front during which the Austrians drove back Moreau's right (southern) flank and nearly captured his artillery park. When Moreau got ready to fight the following day, he discovered that the Austrians had slipped away and were crossing the Danube. Both armies lost about 3,000 men.[44]

Similarly, Jourdan experienced a setback in the north, during a clash at Sulzbach on 17 August, when Paul Kray's Austrians inflicted losses of 1,000 killed and wounded and 700 captured on the French while suffering losses of 900 killed and wounded and 200 captured. Despite their losses, the French continued their advance.[38] Wartensleben's army retreated behind the river Naab on 18 August and, as Jourdan closed up to the Naab,[40] he posted Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte's division at Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz to observe Charles, hoping that would keep the Austrians from hitting him by surprise.[55] Unbeknownst to them, Charles was receiving reinforcements south of the Danube that brought his strength up to 60,000 troops. He left 35,000 soldiers under the command of Latour to contain the Army of the Rhine and Moselle along the Danube.[44]

United Habsburg front

By now Charles clearly understood that if he could unite with Wartenbsleben, he could pick off both the French armies in succession. Having sufficient reinforcements, and having transferred his supply line from Vienna to Bohemia, he planned to move north to unite with Wartensleben: if the stubborn old man would not come to him, the young archduke would go to the stubborn old man. With 25,000 of his best troops, Charles crossed to the north bank of the Danube at Regensburg.[55]

On 22 August 1796, Charles and Friedrich Joseph, Count of Nauendorf, encountered Bernadotte's division at Neumarkt.[38] The outnumbered French were driven northwest through Altdorf bei Nürnberg to the river Pegnitz. Leaving Friedrich Freiherr von Hotze with a division to pursue Bernadotte, Charles thrust north at Jourdan's right flank. The French general fell back to Amberg as Charles and Wartensleben's forces converged on the Army of Sambre and Meuse. On 20 August, Moreau sent Jourdan a message vowing to closely follow Charles, which he did not do.[56] In the Battle of Amberg on 24 August, Charles defeated the French and destroyed two battalions of their rearguard.[55] The Austrians lost 400 killed and wounded out of 40,000 troops. Of a total of 34,000 soldiers, the French suffered losses of 1,200 killed and wounded plus 800 men and two colors captured.[48] Jourdan retreated first to Sulzbach and then behind the river Wiesent where Bernadotte joined him on 28 August. Meanwhile, Hotze reoccupied Nürnberg. Jourdan, who had expected Moreau to keep Charles occupied in the south, now found himself facing a numerically superior enemy.[55]

.JPG.webp)

As Jourdan fell back to Schweinfurt, he saw a chance to retrieve his campaign by offering battle at Würzburg, an important stronghold on the river Main.[57] At this point, the petty jealousies and rivalries that had festered in the French Army over the summer came to a head. Jourdan had a spat with his wing commander Kléber and that officer suddenly resigned his command. Two generals from Kléber's clique, Bernadotte and Colaud, both made excuses to leave the army immediately. Faced with this mutiny, Jourdan replaced Bernadotte with General Henri Simon and split up Colaud's units among the other divisions.[58] With his reorganized troops, Jourdan marched south with 30,000 men of the infantry divisions of Simon, Jean Étienne Championnet, and Paul Grenier, and with the reserve cavalry of Jacques Philippe Bonnaud. Lefebvre's division, 10,000-strong, remained at Schweinfurt to cover a possible retreat, if needed.[57]

Anticipating Jourdan's move, Charles rushed his army toward battle at Würzburg on 1 September.[57] Marshaling the divisions of Hotze, Sztáray, Kray, Johann Sigismund Riesch, Johann I Joseph, Prince of Liechtenstein and Wartensleben, the Austrians won the Battle of Würzburg on 3 September, forcing the French to retreat to the river Lahn. Charles lost 1,500 casualties out of 44,000 troops there, while inflicting 2,000 casualties on the outnumbered French.[59] Another authority gave French losses as 2,000 killed and wounded plus 1,000 men and seven guns captured, while Austrian losses numbered 1,200 killed and wounded and 300 captured. Regardless, the losses at Würzburg compelled the French to lift the siege of Mainz on 7 September, and to move those troops to reinforce their lines further east.[60]

On 10 September, Marceau-Desgraviers reinforced the much-pressed Army of Sambre and Meuse with 12,000 troops that had been blockading the east side of Mainz. Jean Hardy's division on the west side of Mainz retreated to the Nahe, and dug in there. At this point, the French government belatedly transferred two divisions commanded by Jacques MacDonald and Jean Castelbert de Castelverd from France's idle Army of the North. MacDonald's division stopped at Düsseldorf while Castelverd's was placed in the French line on the lower Lahn. These reinforcements brought Jourdan's strength up to 50,000, which would have given him an edge on Charles, except that his abandonment of the sieges at Mainz, and later Mannheim and Philippsburg, released 16,200 and 11,630 Habsburg troops (respectively) to reinforce Charles' already overwhelming numbers.[61]

Moreau seemed oblivious to Jourdan's situation. Still far to the east of Jourdan, Moreau crossed to the south bank of the Danube on 19 August, leaving only Antoine Guillaume Delmas's division on the north bank.[62] By no later than the 20th, Moreau was aware that Charles had recrossed the Danube, heading north, but instead of pursuing him, the French general pressed eastward toward the river Lech. Ferino's right wing, which had been wandering with seeming aimlessness around upper Swabia and Bavaria, finally rejoined the Army of Rhine and Moselle on 22 August, although Delaborde's division remained well to the south. Ferino's only notable action was repulsing a night attack by the 5,000–6,000-man Army of Condé at Kammlach on 13–14 August. The French Royalists and their mercenaries sustained 720 casualties, while Ferino lost a number of prisoners. In this action, Captain Maximilien Sébastien Foy led a Republican horse artillery battery with distinction.[63] Facing the southernmost wing of the Army of the Rhine and Moselle, the combative Latour rashly stood to fight on the Lech near Augsburg on 24 August. Despite rising waters in which some soldiers drowned, Saint-Cyr and Ferino attacked across the river.[64] In the Battle of Friedberg the French crushed an Austrian infantry regiment, inflicting losses of 600 killed and wounded plus 1,200 men and 17 field guns captured. French casualties numbered 400.[48]

Over the next few days, Jourdan's army withdrew again to the west bank of the Rhine. After his disastrous panic at Diez, Castelverd held east bank entrenchments at Neuwied and Poncet crossed at Bonn while the other divisions retired behind the Sieg. Jourdan handed over command to Pierre de Ruel, marquis de Beurnonville, on 22 September. Charles left 32,000 to 36,000 troops in the north and 9,000 more in Mainz and Mannheim, moving south with 16,000 to help intercept Moreau.[65] Franz von Werneck was placed in charge of the northern force.[66] Though Beurnonville's army grew to 80,000 men, he remained completely passive in the fall and winter of 1796.[67] The disgraced Castelverd was later replaced by Jacques Desjardin.[68]

| Date Location | French | Coalition | Victor | Operation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 September Würzburg |

30,000 | 30,000 | Habsburg | Unfortunately for Moreau, Jourdan's drubbing at Amberg, followed by a second defeat at Würzburg, ruined the French offensive; the French lost any chance of reuniting their front; both Moreau and Jourdan had to withdraw to the west.[48] | ||||||

| 7 September End of Mainz blockade |

36,000 | 5,0000 | Habsburg | Once Charles defeated Jourdan's army at Würzburg, Moreau had to withdraw his force from Mainz. | ||||||

| 9 September Wiesbaden |

15,000 | 12,000 | Habsburg | Several of the Archduke's forces attacked Jourdan's rearguard. This action forced Jourdan's army to consolidate its front further away from Moreau's line of retreat. | ||||||

| 16–18 September Limburg and Altenkirchen |

45,000 | 20,000 | Habsburg | On 16–18 September Charles defeated the Army of Sambre & Meuse in the Battle of Limburg.[19] Kray assaulted Grenier's troops on the French left wing at Giessen but was repulsed. In the struggle, Bonnaud was badly wounded and died six months later. Meanwhile, Charles made his main effort against André Poncet's division of Marceau's right wing at Limburg an der Lahn. After an all-day combat, Poncet's lines still held except for a small bridgehead at nearby Diez. Though not threatened, that night Jean Castelbert de Castelverd, who was holding the bridgehead, panicked and withdrew his division without orders from Marceau-Desgraviers. With a gaping hole on their right, Marceau-Desgraviers and Bernadotte (now returned to his division) made a fighting withdrawal to Altenkirchen, allowing the left wing to escape. Marceau-Desgraviers was fatally wounded on the 19th and died the next morning.[69] This permanently severed the only possible link between Jourdan's and Moreau's armies, leaving Charles free to focus on the Army of the Rhine and Moselle. | ||||||

| 17 September Blockade of Ehrenbreitenstein |

unknown | 2,600 | Habsburg | The Habsburg's contingent had been stranded in the fortress since 9 June by portions of Jourdan's rearguard. | ||||||

| 18 September Second Kehl |

7,000 | 5,000 | Stalemate | Initially the Austrians were able to take the river crossings at Kehl, but French reinforcements pushed them off the bridges. By the end of the day, the French could not break the Austrian hold on all east shore approaches to the bridges, and the Austrians established a strong cordon that forced Moreau to move south to the remaining bridgehead at Huningen. Lazare Hoche was killed in action.[70] | ||||||

| 2 October Biberach |

35,000 | 15,000 | French | At Biberach an der Riss, 35 km (22 mi) southwest of Ulm, the French army, now in retreat, paused to savage the pursuing Coalition force, who were following too closely. As the outnumbered Latour doggedly followed the French retreat, Moreau lashed out at him at Biberach. For a loss of 500 soldiers killed and wounded, Moreau's troops inflicted 300 killed and wounded and captured 4,000 prisoners, 18 artillery pieces, and two colors. After the engagement, Latour followed the French at a more respectful distance.[71] | ||||||

| All troop counts and operational objectives, unless otherwise noted, from Smith, pp. 111–132. | ||||||||||

Moreau's retreat

While Charles and his army ruined the French strategy in the north, Moreau moved too slowly in Bavaria. Although Saint-Cyr captured a crossing of the river Isar at Freising on 3 September, Latour and his Habsburg troops regrouped at Landshut. Latour, having visions of destroying Moreau's army in the south, pressed hard against the French rearguard. Saint-Cyr's center was directed to assault Latour's center while Ferino was instructed to turn the Austrian left under Condé and Karl Mercandin. Ferino was too distant to intervene, but his colleagues drove back the Austrians and seized Biberach an der Riss, together with 4,000 Austrian prisoners, 18 guns and two colors.[72] The French lost 500 killed and wounded while the Austrians lost 300, but this was the last significant French victory of the campaign.[71] Moreau sent Desaix to the Danube's north bank on 10 September, but Charles ignored this threat as the distraction it was.[73]

It soon became obvious that, like Jourdan's force in the north, the Army of Rhine and Moselle was isolated and too far extended, and had to retreat. In the first half of September, in Bavaria, Latour's 16,960 men hounded Moreau's army in a drive to the east while Fröhlich's 10,906 soldiers pushed from the south. Nauendorf's 5,815 men went north, and Petrasch's 5,564 troops continued their push to the west.[74] On 18 September, Petrasch and 5,000 Austrians briefly captured the fortified bridgehead at Kehl before being driven out by Balthazar Alexis Henri Schauenburg's counterattack. Each side suffered 2,000 killed, wounded and captured.[71] Instead of burning the bridge, though, as they should have done, Petrasch's men plundered the French camp and lost the opportunity to trap Schauenburg's army on the west bank of the Rhine.[73]

Moreau began retreating on 19 September.[75] By the 21st the Army of Rhine and Moselle reached the river Iller.[76] On 1 October, the Austrians attacked, only to be repulsed by a brigade under Claude Lecourbe. On 2 October, Latour's army was deployed in a weak position with the river Riss behind it. Moreau ordered Desaix's left wing to attack Latour's right, commanded by Siegfried von Kospoth. At the same time, Moreau attacked with 39,000 troops, defeated Latour's 24,000 men in the Battle of Biberach.[77]

Moreau wanted to retreat through the Black Forest via the Kinzig river valley, but Nauendorf blocked that route. Instead, Saint-Cyr's column led the way over the Höllenthal, breaking through the Austrian net at Neustadt and reaching Freiburg im Breisgau on 12 October. Moreau's supply trains took a route down the river Wiese to Hüningen. The French general wanted to reach Kehl farther down the Rhine, but by this time Charles was barring the way with 35,000 soldiers. For his trains to get away, Moreau needed to hold his position for a few days.[78] The Battle of Emmendingen was fought on 19 October, the 32,000 French losing 1,000 killed and wounded plus 1,800 men and two guns captured. The Austrians sustained 1,000 casualties out of 28,000 troops engaged. Beaupuy and Wartensleben were both killed.[71] There was some fighting on the 20th, but when Charles advanced on 21 October the French were gone.[78]

Moreau sent Desaix's wing to the west bank of the Rhine at Breisach and, with the main part of his army, offered battle at Schliengen. Saint-Cyr held the low ground on the left near the Rhine while Ferino defended the hills on the right. Charles hoped to turn the French right and trap Moreau's army against the Rhine.[79] In the Battle of Schliengen on 24 October, the French suffered 1,200 casualties out of 32,000 engaged. The Austrians counted 800 casualties out of 36,000 men.[80] The French held off the Austrian attacks but retreated the next day and recrossed to the west bank of the Rhine on 26 October.[79] In the south, the French held two east-bank bridgeheads. Moreau ordered Desaix to defend Kehl while Ferino and Abbatucci were to hold Hüningen.[81]

| Date Location | French | Coalition | Victor | Operation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 October Emmendingen |

32,000 | 28,000 | Habsburg | Both sides had been hampered by heavy rains; the ground was soft and slippery, and the river Rhine and Elz had flooded. This increased the hazards of mounted attack, because the horses could not get a good footing. Charles' force pursued the French, although carefully. The French attempted to slow their pursuers by destroying bridges, but the Austrians managed to repair them and to cross the swollen rivers despite the high waters. Upon reaching a few miles east of Emmendingen, the Archduke split his force into four columns. Friedrich Joseph, Count of Nauendorf's column, in the upper Elz, had eight battalions and 14 squadrons, advancing southwest to Waldkirch; Wartensleben had 12 battalions and 23 squadrons advancing south to capture the Elz bridge at Emmendingen. Latour, with 6,000 men, was to cross the foothills via Heimbach and Malterdingen, and capture the bridge of Köndringen, between Riegel and Emmendingen, and Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg's column held Kinzingen, about 3.2 km (2 mi) north of Riegel. Frölich and Condé (part of Nauendorf's column) were to pin down Ferino and the French right wing in the Stieg valley. Nauendorf's men were able to ambush St.-Cyr's advance; Latour's columns attacked Beaupuy at Matterdingen, killing the general and throwing his column into confusion. Wartensleben, in the center, was held up by French riflemen until his third (reserve) detachment arrived to outflank them; the French retreated across the rivers, destroying all the bridges.[82] | ||||||

| 24 October Schliengen |

32,000 | 24,000 | Habsburg | After retreating from Freiburg im Breisgau, Moreau established his army along a ridge of hills, in a 11-kilometer (7 mi) semi-circle on heights that commanded the terrain below. Given the severe condition of the roads at the end of October, Charles could not flank the right French wing. The French left wing lay too close to the Rhine, and the French center was unassailable. Instead, he attacked the French flanks directly, and in force, which increased casualties for both sides. The Duc d'Enghien led a spirited (but unauthorized) attack on the French left, cutting their access to a withdrawal through Kehl.[83] Nauendorf's column marched all night and half of the day, and attacked the French right, pushing them further back. In the night, while Charles planned his next day's attack, Moreau began the withdrawal of his troops toward Hüningen.[84] Although the French and the Austrians both claimed victory at the time, military historians generally agree that the Austrians achieved a strategic advantage. However, the French withdrew from the battlefield in good order and several days later crossed the Rhine at Hüningen.[85] | ||||||

| All troop counts and operational objectives, unless otherwise noted, from Smith, pp. 111–132. | ||||||||||

Armistice refused and subsequent sieges

Moreau offered Charles an armistice and the Archduke was eager to accept it so that he could send 10,000 reinforcements to Italy, but the Aulic Council directed him to refuse it and to reduce Kehl and Hüningen. While Charles was instructed to reduce the cities, in early January, the French began transferring two divisions to Bonaparte's army in Italy. Bernadotte's 12,000 from the Army of Sambre and Meuse and Delmas's 9,500 from the Army of Rhine and Moselle went south to support Bonaparte's approach to Vienna.[86]

Instead of sending a comparable number of men to Italy to defend against the reinforcements, Charles gave Latour 29,000 infantry and 5,900 cavalry and ordered him to capture Kehl. The Siege of Kehl lasted from 10 November to 9 January 1797, during which the French suffered 4,000 and the Austrians 4,800 casualties. By a negotiated agreement, the French surrendered Kehl in return for an undisturbed withdrawal of the garrison into Strasbourg. Similarly, the French handed over the east-bank bridgehead at Hüningen on 5 February.[87]

| Date Location | French | Coalition | Victor | Operation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 October – 9 January 1797 Kehl |

20,000[88] | 40,000 | Habsburg | The French defenders under Louis Desaix and the overall commander of the French force, Jean Victor Marie Moreau, almost upset the siege when they executed a sortie that nearly captured the Austrian artillery park; the French managed to capture 1,000 Austrian troops in the melee. On 9 January the French general Desaix proposed the evacuation to General Latour and they agreed that the Austrians would enter Kehl the next day, on 10 January at 16:00. The French immediately repaired the bridge, rendered passable by 14:00, which gave them 24 hours to evacuate everything of value and to raze everything else. By the time Latour took possession of the fortress, nothing remained of any use: all palisades, ammunition, even the carriages of the bombs and howitzers, had been evacuated. The French ensured that nothing remained behind that could be used by the Austrian/Imperial army; even the fortress itself was but earth and ruins. The siege concluded 115 days after its investment, following 50 days of open trenches, the point at which active fighting began.[89] | ||||||

| 27 November – 1 February 1797 Hüningen |

25,000 | 9,000 | Habsburg | Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg's force initiated the siege within days of the Austrian victory at the Battle of Schliengen. Most of the siege ran concurrently with the siege at Kehl, which concluded on 9 January 1797. Troops engaged at Kehl marched to Hüningen in preparation for a major assault, but the French defenders capitulated on 1 February 1797. The French commander, Jean Charles Abbatucci, was killed in the early days of the fighting, and replaced by Georges Joseph Dufour. The trenches, opened originally in November, had refilled with winter rain and snow in the intervening weeks. Fürstenberg ordered them opened again, and the water drained out on 25 January. The Coalition force secured the earthworks surrounding the trenches. On 31 January the French failed to push the Austrians out.[90] Charles arrived that day and met with Fürstenberg at nearby Lörrach. The night of 31 January / 1 February was relatively tranquil, marred only by ordinary artillery fire and shelling.[91] At mid-day 1 February 1797, as the Austrians prepared to storm the bridgehead, General of Division Dufour pre-empted what would have been a costly attack for both sides, offering to surrender the position. On 5 February, Fürstenberg finally took possession of the bridgehead.[92] | ||||||

| All troop counts and operational objectives, unless otherwise noted, from Smith, pp. 111–132. | ||||||||||

Aftermath

Moreau's ability to transfer troops to Italy, and Charles' inability to do so, made a fundamental difference in the outcome of the Italian campaign of 1796. At the outset of the campaign, the French military planners calculated that the best route to Vienna was through Germany, not Italy; consequently they focused the bulk of their force at the Rhine, long viewed by both the French and the Holy Roman Empire as the principal barrier between the two polities. The army that held the opposite bank controlled access to the crossings. Reflecting this philosophy, the Italian campaign received only 37,000 men and 60 guns to oppose more than 50,000 Allied troops in the theater. Nevertheless, Napoleon was successful at isolating the Sardinians from their Austrian allies at the Battle of Millesimo (13–14 April), and at the Battle of Lodi a month later. He then isolated the Neopolitans from the Austrians at the Battle of Borghetto on 30 May 1796.[93]

While engaged in defending the besieged bridgeheads at Kehl and Huningen, Moreau had been moving troops south to support Napoleon. The Austrian defeat at the Battle of Rivoli in January 1797, with some 14,000 Allied casualties, allowed Napoleon to surround and capture an Austrian relief column near Mantua. Soon after, the city itself surrendered to the French, who continued their advance eastward towards Austria. After a brief campaign during which the Austrian army was commanded by Charles, the French advanced to Judenburg, within 161 km (100 mi) of Vienna, and the Austrians agreed to a five-day truce. Napoleon claimed to have taken 150,000 prisoners, 170 standards, 500 pieces of heavy artillery, 600 field pieces, five pontoon trains, nine ships of the line, 12 frigates, 12 corvettes and 18 galleys; in an age when battlefield success was calculated not only by possession of the battlefield but also by the count of prisoners and spoils, the campaign was a decisive victory. In the Rhineland, Charles returned to the status quo antebellum.[94]

On 18 April 1797, Austria and France agreed to an armistice; this was followed by five months of negotiation, leading to the Peace of Campo Formio, which ended the War of the First Coalition, on 18 October 1797. The peace treaty was to be followed up by the Congress at Rastatt at which the parties would divide the spoils of war. Campo Formio's terms held until 1798, when both groups recovered their military strength and began the War of the Second Coalition. Despite the renewal of military action, the Congress continued its meetings in Rastatt until the assassination of the French delegation in April 1799.[95]

Commentary

Dodge called Charles' military operations "masterful" but noted the difference in results between the Rhine and Italian campaigns. "In Germany, each opponent ended where he began; Bonaparte won all northern Italy by his new method of conducting war." Dodge credited Moreau with "ordinary talent" and Jourdan with even less. He stated that Carnot's plan of allowing his two northern armies to operate on separated lines contained the element of failure.[96]

In his five-volume analysis of the French Revolutionary Wars, Ramsay Weston Phipps speculated on why Moreau gained renown by the supposed skill of his retreat. Phipps suggested that it was not skillful for Moreau to allow the inferior columns of Latour, Nauendorf and Fröhlich to herd him back to France. Even during his advance, Phipps maintained, Moreau was irresolute.[97] Jean-de-Dieu Soult, who participated in the campaign as an infantry brigadier, noted that Jourdan too made many errors but the French government's errors were worse. The French were unable to pay for supplies because their currency was worthless, so the soldiers stole everything. This ruined discipline and turned the local populations against the French.[98] Jourdan seemed to have an unwarranted faith in Moreau's promise to follow Charles. His decision to give battle at Würzburg was partly done so as not to leave Moreau in the lurch.[99]

Notes and citations

Notes

- Beginning in the sixteenth century, the Holy Roman Empire was organized loosely into ten "circles" (Kreise) or regional groups of ecclesiastical, dynastic and secular polities that coordinated economic, military and political actions. During times of war, the Circles contributed troops to the Habsburg military by drafting (or soliciting volunteers) among their inhabitants. Some circles coordinated their efforts better than others; the Swabian Circle was among the more effective of the Imperial circles at organizing itself and protecting its economic interests. This structure is explained in more detail in James Allen Vann, The Swabian Kreis: Institutional Growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648–1715. Vol. LII, Studies Presented to International Commission for the History of Representative and Parliamentary Institutions. Bruxelles, 1975 and Mack Walker, German Home Towns: Community, State, and General Estate, 1648–1871. Ithaca, Cornell, 1998.

- The Rhine itself looked different in the 1790s than it does in the twenty-first century; in the nineteenth century, the passage from Basel to Iffezheim was "corrected" (straightened) to make year-round transport easier. Between 1927 and 1975, the construction of a canal allowed better control of the water level.[10]

- An autonomous corps, in the Austrian or Imperial armies, was an armed force under command of an experienced field commander. They usually included two divisions but probably not more than three and functioned with high maneuverability and independent action, hence the name. Some, called the Frei-Corps, or independent corps, were used as light infantry before the official formation of such units in the Habsburg Army in 1798 and provided the army's skirmishing and scouting; Frei-Corps were usually raised from the provinces.[17] Some historians maintain that Napoleon solidified the use of the autonomous corps, armies that could function without a great deal of direction, scatter about the countryside but reform again quickly for battle; this was actually a development that first emerged first in the French and Indian War in the British Thirteen Colonies, later in the American Revolutionary War and became widely used in the European military as armies got bigger in the 1790s and during the Napoleonic Wars.[11]

- Habsburg infantry wore white coats.[15]

- Pierre Marie Barthélemy Ferino led Moreau's far right wing, near the border of Baden, Basel and France; Louis Desaix commanded the 10,000 man center near Strasbourg, and Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr directed the left wing. Ferino's wing consisted of three divisions under François Antoine Louis Bourcier, 9,281 infantry and 690 cavalry, Henri François Delaborde, 8,300 infantry and 174 cavalry and Augustin Tuncq, 7,437 infantry and 432 cavalry. Desaix's command counted three divisions led by Michel de Beaupuy, 14,565 infantry and 1,266 cavalry, Antoine Guillaume Delmas, 7,898 infantry and 865 cavalry and Charles Antoine Xaintrailles, 4,828 infantry and 962 cavalry. Gouvion Saint-Cyr's wing had two divisions commanded by Guillaume Philibert Duhesme, 7,438 infantry and 895 cavalry and Alexandre Camille Taponier, 11,823 infantry and 1,231 cavalry.[22]

- The French Army designated two kinds of infantry: d'infanterie légère, or light infantry, to provide skirmishing cover for the troops that followed, principally d'infanterie de ligne, which fought in tight formations.[32]

Citations

- Timothy Blanning. The French Revolutionary Wars, New York, Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 41–59.

- (in French) Roger Dupuy, Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine. La République jacobine, Paris, Seuil, 2005, p. 156.

- Jean Paul Bertaud, R. R. Palmer (trans). The Army of the French Revolution: From Citizen-Soldiers to Instrument of Power, Princeton University Press, 1988, pp. 283–290; Ramsay Weston Phipps, The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II: The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle, Pickle Partners Publishing, (1932– ), v. II, p. 184; (in French)Charles Clerget, Tableaux des armées françaises: pendant les guerres de la Révolution, [Paris], R. Chapelot, 1905, p. 62; and Digby Smith, Napoleonic Wars Data Book. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, Stackpole, 1999, pp. 111, 120.

- Joachim Whaley, Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume I: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493–1648, Oxford University Press, 2012, vol.1, pp. 17–20.

- Mack Walker, German Home Towns: Community, State, and General Estate, 1648–1871, Cornell University Press, 1998, Chapters 1–3.

- Thomas P. Knepper, The Rhine. Handbook for Environmental Chemistry Series, Part L, New York, Springer, 2006, pp. 5–19.

- Knepper, pp. 19–20.

- (in German) Johann Samuel Ersch, Allgemeine encyclopädie der wissenschaften und künste in alphabetischer folge von genannten schrifts bearbeitet und herausgegeben. Leipzig, J. F. Gleditsch, 1889, pp. 64–66.

- Thomas Curson Hansard (ed.) .Hansard's Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 1803, Official Report. Vol 1, London, HMSO, 1803, pp. 249–252.

- (in German) Helmut Volk. "Landschaftsgeschichte und Natürlichkeit der Baumarten in der Rheinaue." Waldschutzgebiete Baden-Württemberg, Band 10, 2006, pp. 159–167.

- David Gates, The Napoleonic Wars 1803–1815, New York, Random House, 2011, Chapter 6.

- Theodore Ayrault Dodge, Warfare in the Age of Napoleon: The Revolutionary Wars Against the First Coalition in Northern Europe and the Italian Campaign, 1789–1797, Leonaur Ltd, 2011, pp. 286–287.

- David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon, Macmillan, 1966, pp. 46–47.

- Phipps, v. 2, p. 278.

- Gunther E. Rothenberg, "The Habsburg Army in the Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815)". Military Affairs, (Feb 1973) 37:1, pp. 1–5.

- Dodge, pp. 286–287.

- Philip Haythornthwaite, Austrian Army of the Napoleonic Wars (1): Infantry. Oxford, Osprey Publishing, 2012, p. 24.

- Smith, pp. 111–114.

- Smith, p. 124.

- Smith, pp. 111–114; Rothenberg, pp. 2–3.

- Chandler, pp. 46–47; Smith, p. 111.

- Smith, p. 111.

- Chandler, pp. 46–47; Smith, pp. 111–114.

- J. Rickard, Combat of Siegburg, 1 June 1796, History of War, 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2014 .

- J. Rickard, First Battle of Altenkirchen, 4 June 1796, History of War, 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Digby Smith and Leopold Kudrna, Austrian Generals of 1792–1815: Württemberg, Ferdinand Friedrich August Herzog von, Napoleon Series, Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Dodge, p. 288.

- Smith, p. 115.

- Smith, p. 114.

- (in German) Charles, Archduke of Austria. Ausgewählte Schriften weiland seiner Kaiserlichen Hoheit des Erzherzogs Carl von Österreich, Vienna, Braumüller, 1893–94 v. 2, pp. 72, pp. 153–154.

- Charles, pp. 153–154 and Thomas Graham, 1st Baron Lynedoch, The History of the Campaign of 1796 in Germany and Italy, London, (np), 1797, pp. 18–22.

- Smith, p. 15.

- Graham, pp. 18–22.

- Smith, p. 116.

- Dodge, p. 290.

- (in German) Charles, pp. 72, 153.

- Charles, pp. 153–154 and Graham, pp. 18–22.

- Smith, p. 120.

- Dodge, p. 290; Smith, p. 117.

- Dodge, p. 296.

- Smith, p. 117.

- Phipps, p. 302.

- Smith, pp. 115–116.

- Dodge, pp. 292–293.

- Phipps, p. 292.

- J. Rickard, Battle of Ettlingen, 9 July 1796, History of War, 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Phipps, p. 293.

- Smith, pp. 120–121.

- Barton, Dunbar Plunket (1914). Bernadotte: The First Phase. P. 146.

- Ibid. Pp. 146-154.

- Barton, Pp. 142-147.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. Pp. 148-154.

- Smith, p. 121.

- Dodge, p. 297.

- Phipps, pp. 328–329.

- Dodge, p. 298.

- Phipps, pp. 348–349.

- Dodge, p. 301.

- Smith, p. 122.

- Phipps, pp. 353–354.

- Phipps, p. 326.

- Phipps, pp. 330–332.

- Phipps, pp. 334–335.

- Phipps, p. 366.

- Phipps, p. 420.

- Dodge, p. 344.

- Phipps, p. 389.

- Phipps, pp. 360–364.

- John Holland Rose, The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Era, 1789–1815, Cambridge Historical Series, Cambridge University Press, (1935), 2013, p. 102.

- Smith, p. 125.

- Dodge, pp. 304–306.

- Dodge, pp. 302–303.

- Phipps, p. 367.

- Phipps, p. 369.

- Dodge, p. 304.

- Phipps, p. 371.

- Dodge, pp. 306–308.

- Dodge, pp. 308–310.

- Smith, p. 126.

- Dodge, p. 311.

- (in German) Ersch, pp. 64–66; Smith, p. 125.

- The Annual Register, World Events 1796. London, FC and J Rivington, 1813, p. 208.

- Graham, pp. 124–25.

- Phillip Cuccia, Napoleon in Italy: The Sieges of Mantua, 1796–1799, Oklahoma, University of Oklahoma Press, 2014, pp. 87–93; Smith, pp. 12–13, 125–133.

- Phipps, pp. 405–406.

- Phipps, pp. 393–394; Smith, p. 132.

- John Philippart (trans), Memoires etc. of General Moreau, London, A.J. Valpy, 1814, p. 279.

- Philippart, p. 127; Smith, p. 131.

- Sir Archibald Alison, 1st Baronet. History of Europe from the Commencement of the French Revolution to the Restoration of the Bourbons, Volume 3. Edinburgh, W. Blackwood, 1847, p. 88.

- (in French) Christian von Mechel, Tableaux historiques et topographiques ou relation exacte.... Basel, 1798, pp. 64–72.

- Philippart, p. 127; Alison, pp. 88–89; Smith, p. 132.

- Smith, pp. 111–116.

- Alison, p. 378; Smith, pp. 131–133, for troop counts.

- Georges Lefebvre, The French Revolution: From 1793–1799. II. New York: Columbia University Press, 1964, pp. 199–201, 234. Smith, pp. 131–133, for troop movements.

- Dodge, pp. 311–313.

- Phipps, pp. 400–402.

- Phipps, pp. 395–396.

- Phipps, p. 347.

Sources

Print

- Archibald, Alison (1847). History of Europe from the Commencement of the French Revolution to the Restoration of the Bourbons. III. Edinburgh: Blackwood. OCLC 986459607.

- Barton, Sir Dunbar. Bernadotte: The First Phase. London: John Murray, 1914.

- Bertrand, Jean Paul, R.R. Palmer (trans). From Citizen-Soldiers to Instrument of Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-69-105537-4

- Blanning, Timothy (1998). The French Revolutionary Wars. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-340-56911-5.

- Blanning, Timothy (1983). The French Revolution in Germany. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822564-5.

- Chandler, David G. (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 50614349.

- Archduke of Austria, Charles (2004). Nafziger, George (ed.). Geschichte des Feldzuges von 1796 in Deutschland (in German). West Chester, OH. OCLC 75199197.

- Archduke of Austria, Charles (1893–94). F. X. Malcher (ed.). Ausgewählte Schriften (in German). Vienna. OCLC 558057478.

- Clerget, Charles (1905). Tableaux des armées françaises: pendant les guerres de la Révolution (in French). Paris: R. Chapelot. OCLC 252446008.

- Cuccia, Phillip (2014). Napoleon in Italy: The Sieges of Mantua, 1796–1799. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma. ISBN 978-0-8061-4445-0.

- Dodge, Theodore Ayrault (2011). Warfare in the Age of Napoleon: The Revolutionary Wars against the First Coalition in Northern Europe and the Italian Campaign, 1789–1797. London: Leonaur. ISBN 978-0-85706-598-8.

- Dupuy, Roger (2005). La période jacobine: terreur, guerre et gouvernement révolutionnaire: 1792–1794 (in French). Paris: Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-039818-3.

- Ersch, Johann Samuel (1889). Allgemeine encyclopädie der wissenschaften und künste in alphabetischer folge von genannten schrifts bearbeitet und herausgeben (in German). Leipzig: J. F. Gleditsch. pp. 64–66. ISBN 978-3-7411-7213-7.

- Gates, David (2011). The Napoleonic Wars 1803–1815. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-7126-0719-3.

- Graham, Thomas, 1st Baron Lynedoch, (sometimes attributed to). The History of the Campaign of 1796 in Germany and Italy, London, (np), 1797. OCLC 277280926

- Hansard, Thomas C., ed. (1803). Hansard's Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 1803, Official Report. I. London: HMSO. OCLC 85790018.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip (2012). Austrian Army of the Napoleonic Wars: Infantry. I. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-78200-702-9.

- Knepper, Thomas P. (2006). The Rhine. Handbook for Environmental Chemistry Series. Part L. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-29393-4.

- Lefebvre, Georges (1964). The French Revolution: From 1793–1799. II. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-02519-5. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- Mechel, Christian von (1798). Tableaux historiques et topographiques ou relation exacte... Basel. pp. 64–72. OCLC 715971198.

- Philippart, John (1814). Memoires etc. of General Moreau. London: A. J. Valpy. OCLC 45089676.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011). The Armies of the First French Republic: The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle. II. Sevenoaks: Pickle Partners. ISBN 978-1-908692-25-2.

- Rose, John Holland (2013) [1935]. The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Era, 1789–1815. Cambridge Historical Series. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-66232-2.

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (Feb 1973), "The Habsburg Army in the Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815)". Military Affairs, 37:1, pp. 1–5.

- Rothenburg, Gunther E. (1980). The Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20260-4.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 978-1-85367-276-7.

- The Annual Register: World Events 1796. London: F. C. and J. Rivington. 1813. OCLC 872988630.

- Vann, James Allen (1975). The Swabian Kreis: Institutional Growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648–1715. LII. Brussels: Studies Presented to International Commission for the History of Representative and Parliamentary Institutions. OCLC 923507312.

- Volk, Helmut (2006). "Landschaftsgeschichte und Natürlichkeit der Baumarten in der Rheinaue". Waldschutzgebiete Baden-Württemberg (in German). X: 159–167. OCLC 939802377.

- Walker, Mack (1998). German Home Towns: Community, State and General Estate, 1648–1871. Ithaca, N. Y.: Cornell University Press. OCLC 2276157.

- Whaley, Joachim (2012). Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493–1648. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968882-1.

Web

- Rickard, J. Battle of Ettlingen, 9 July 1796, History of War, 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Rickard, J. Combat of Siegburg, 1 June 1796, History of War, 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Rickard, J. First Battle of Altenkirchen, 4 June 1796, History of War, 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Smith, Digby and Leopold Kudrna. Austrian Generals of 1792–1815: Württemberg, Ferdinand Friedrich August Herzog von, Napoleon Series. Retrieved 30 April 2014.