Rocky Mountain spotted fever

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a bacterial disease spread by ticks.[9] It typically begins with a fever and headache, which is followed a few days later with the development of a rash.[3] The rash is generally made up of small spots of bleeding and starts on the wrists and ankles.[10] Other symptoms may include muscle pains and vomiting.[3] Long-term complications following recovery may include hearing loss or loss of part of an arm or leg.[3]

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Blue disease,[1] Brazilian spotted fever, Tobia fever, new world spotted fever, tick- borne typhus fever, Sao Paulo fever[2] |

| |

| Petechial rash on the arm caused by Rocky Mountain spotted fever | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Early: Fever, headache[3] Later: Rash[3] |

| Complications | Hearing loss, loss of limbs[3] |

| Usual onset | 2 to 14 days after infection[2] |

| Duration | 2 weeks[2] |

| Causes | Rickettsia rickettsii spread ticks[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Zika fever, dengue, chikungunya, Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis, Pacific Coast tick fever, rickettsialpox[6][7] |

| Treatment | Doxycycline[8] |

| Prognosis | 0.5% risk of death[6] |

| Frequency | < 5,000 cases per year (USA)[6] |

The disease is caused by Rickettsia rickettsii, a type of bacterium that is primarily spread to humans by American dog ticks, Rocky Mountain wood ticks, and brown dog ticks.[4] Rarely the disease is spread by blood transfusions.[4] Diagnosis in the early stages is difficult.[5] A number of laboratory tests can confirm the diagnosis but treatment should be begun based on symptoms.[5] It is within a group known as spotted fever rickettsiosis, together with Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis, Pacific Coast tick fever, and rickettsialpox.[6]

Treatment of RMSF is with the antibiotic doxycycline.[8] It works best when started early and is recommended in all age groups, as well as during pregnancy.[8] Antibiotics are not recommended for prevention.[8] Approximately 0.5% of people who are infected die as a result.[6] Before the discovery of tetracycline in the 1940s, more than 10% of those with RMSF died.[6]

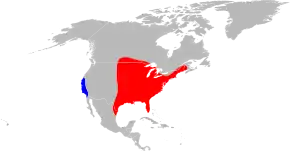

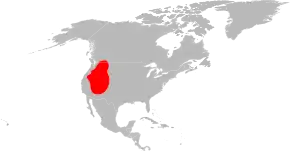

Fewer than 5,000 cases are reported a year in the United States, most often in June and July.[6] It has been diagnosed throughout the contiguous United States, Western Canada, and parts of Central and South America.[10][2] Rocky Mountain spotted fever was first identified in the 1800s in the Rocky Mountains.[10]

Signs and symptoms

Spotted fever can be very difficult to diagnose in its early stages, due to the similarity of symptoms with many different diseases.

People infected with R. rickettsii usually notice symptoms following an incubation period of one to two weeks after a tick bite. The early clinical presentation of Rocky Mountain spotted fever is nonspecific and may resemble a variety of other infectious and noninfectious diseases.

Initial symptoms:

- Fever

- Nausea

- Emesis (vomiting)

- Severe headache

- Muscle pain

- Lack of appetite

- Parotitis in some cases (somewhat rare)

Later signs and symptoms:

- Maculopapular rash

- Petechial rash

- Abdominal pain

- Joint pain

- Conjunctivitis

- Forgetfulness

The classic triad of findings for this disease are fever, rash, and history of tick bite. However, this combination is often not identified when patients initially present for care. The rash has a centripetal, or "inward" pattern of spread, meaning it begins at the extremities and courses towards the trunk.

Rash

The rash first appears two to five days after the onset of fever, and it is often quite subtle. Younger patients usually develop the rash earlier than older patients. Most often the rash begins as small, flat, pink, nonitchy spots (macules) on the wrists, forearms, and ankles. These spots turn pale when pressure is applied and eventually become raised on the skin. The characteristic red, spotted (petechial) rash of Rocky Mountain spotted fever is usually not seen until the sixth day or later after onset of symptoms, but this type of rash occurs in only 35 to 60% of patients with Rocky Mountain spotted fever. The rash involves the palms or soles in as many as 80% of people. However, this distribution may not occur until later on in the course of the disease. As many as 15% of patients may never develop a rash.[11]

Complications

People can develop permanent disabilities including "cognitive deficits, ataxia, hemiparesis, blindness, deafness, or amputation following gangrene".[7]

Cause

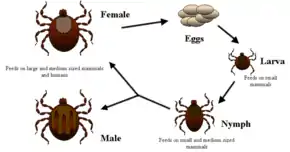

Ticks are the natural hosts of the disease, serving as both reservoirs and vectors of R. rickettsii. Ticks transmit the bacteria primarily by their bites. Less commonly, infections may occur following exposure to crushed tick tissues, fluids, or tick feces.

A female tick can transmit R. rickettsii to her eggs in a process called transovarial transmission. Ticks can also become infected with R. rickettsii while feeding on blood from the host in either the larval or nymphal stage. After the tick develops into the next stage, the R. rickettsii may be transmitted to the second host during the feeding process. Furthermore, male ticks may transfer R. rickettsii to female ticks through body fluids or spermatozoa during the mating process. These types of transmission represent how generations or life stages of infected ticks are maintained. Once infected, the tick can carry the pathogen for life.

Rickettsiae are transmitted through saliva injected while a tick is feeding. Unlike Lyme disease and other tick-borne pathogens that require a prolonged attachment period to establish infection, a person can become infected with R. rickettsii in a feeding time as short as 2 hours.[12] In general, about 1-3% of the tick population carries R. rickettsii, even in areas where the majority of human cases are reported. Therefore, the risk of exposure to a tick carrying R. rickettsii is low.

The disease is spread by the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), Rocky Mountain wood tick (D. andersoni), brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus), and Amblyomma sculptum.[13][14] Not all of these are of equal importance, and most are restricted to certain geographic areas.

The two major vectors of R. rickettsii in the United States are the American dog tick and the Rocky Mountain wood tick. American dog ticks are widely distributed east of the Rocky Mountains and they also occur in limited areas along the Pacific Coast. Dogs and medium-sized mammals are the preferred hosts of an adult American dog tick, although it feeds readily on other large mammals, including human beings. This tick is the most commonly identified species responsible for transmitting R. rickettsii to humans. Rocky Mountain wood ticks (D. andersoni) are found in the Rocky Mountain states and in southwestern Canada. The lifecycle of this tick may require up to three years for its completion. The adult ticks feed primarily on large mammals. The larvae and nymphs feed on small rodents.

Other tick species have been shown to be naturally infected with R. rickettsii or serve as experimental vectors in the laboratory. These species are likely to play only a minor role in the ecology of R. rickettsii.

Pathophysiology

Entry into host

Rickettsia rickettsii can be transmitted to human hosts through the bite of an infected tick. As with other bacterium transmitted via ticks, the process generally requires a period of attachment of 4 to 6 hours. However, in some cases a Rickettsia rickettsii infection has been contracted by contact with tick tissues or fluids.[15] Then, the bacteria induce their internalization into host cells via a receptor-mediated invasion mechanism.

Researchers believe that this mechanism is similar to that of Rickettsia conorii. This species of Rickettsia uses an abundant cell surface protein called OmpB to attach to a host cell membrane protein called Ku70. It has previously been reported that Ku70 migrates to the host cell surface in the presence of "Rickettsia".[16] Then, Ku70 is ubiquitinated by c-Cbl, an E3 ubiquitin ligase. This triggers a cascade of signal transduction events resulting in the recruitment of Arp2/3 complex. CDC42, protein tyrosine kinase, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, and Src-family kinases then activate Arp2/3. This causes the alteration of local host cytoskeletal actin at the entry site as part of a zipper mechanism.[17] Then, the bacteria is phagocytosized by the host cell and enveloped by a phagosome.[16]

Studies have suggested that rOmpB is involved in this process of adhesion and invasion. Both rOmpA and rOmpB are members of a family of surface cell antigens (Sca) which are autotransporter proteins; they act as ligands for the Omp proteins and are found throughout the rickettsiae.[18]

Exit from host cell

The cytosol of the host cell contains nutrients, adenosine triphosphate, amino acids, and nucleotides which are used by the bacteria for growth. For this reason, as well as to avoid phagolysosomal fusion and death, rickettsiae must escape from the phagosome. To escape from the phagosome, the bacteria secrete phospholipase D and hemolysin C. This causes disruption of the phagosomal membrane and allows the bacteria to escape. Following generation time in the cytoplasm of the host cells, the bacteria utilizes actin based motility to move through the cytosol.[16]

RickA, expressed on the rickettsial surface, activates Arp2/3 and causes actin polymerization. The rickettsiae use the actin to propel themselves throughout the cytosol to the surface of the host cell. This causes the host cell membrane to protrude outward and invaginate the membrane of an adjacent cell.[17] The bacteria are then taken up by the neighboring cell in a double membrane vacuole that the bacteria can subsequently lyse, enabling spread from cell to cell without exposure to the extracellular environment.

Consequences of infection

Rickettsia rickettsii initially infect blood vessel endothelial cells, but eventually migrate to vital organs such as the brain, skin, and the heart via the blood stream. Bacterial replication in host cells causes endothelial cell proliferation and inflammation, resulting in mononuclear cell infiltration into blood vessels and subsequent red blood cell leakage into surrounding tissues. The characteristic rash observed in Rocky Mountain spotted fever is the direct result of this localized replication of rickettsia in blood vessel endothelial cells.[10]

Diagnosis

Even doctors who are familiar with the disease find it hard to diagnose early during infection.

Abnormal laboratory findings seen in patients with Rocky Mountain spotted fever may include a low platelet count, low blood sodium concentration, or elevated liver enzyme levels. Serology testing and skin biopsy are considered to be the best methods of diagnosis. Although immunofluorescent antibody assays are considered some of the best serology tests available, most antibodies that fight against R. rickettsii are undetectable on serology tests during the first seven days after infection.[19]

Differential diagnosis includes dengue, leptospirosis, chikungunya, and Zika fever.[7]

Treatment

Appropriate antibiotic treatment should be started immediately when there is a suspicion of Rocky Mountain spotted fever.[10] Early treatment of Rocky Mountain spotted fever prevents further damage to internal organs. Treatment should not be delayed for laboratory confirmation. Failure to respond to a tetracycline argues against a diagnosis of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Severely ill people may require longer periods before their fever resolves, especially if they have experienced damage to multiple organ systems. Preventive therapy in healthy people who have had recent tick bites is not recommended and may only delay the onset of disease.[20]

Doxycycline (a tetracycline) is the drug of choice for patients with Rocky Mountain spotted fever, being one of the only instances doxycycline is used in children.[21] Treatment typically consists of 100 milligrams every 12 hours, or for children under 45 kg (99 lb) at 4 mg/kg of body weight per day in two divided doses. Treatment should be continued for at least three days after the fever subsides, and until there is unequivocal evidence of clinical improvement. This will be generally for a minimum time of five to ten days.[10] Severe or complicated outbreaks may require longer treatment courses. Doxycycline/ tetracycline is also the preferred drug for patients with ehrlichiosis, another tick-transmitted infection with signs and symptoms that may resemble those of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Chloramphenicol is an alternative drug that can be used to treat Rocky Mountain spotted fever, specifically in pregnancy. However, this drug may be associated with a wide range of side effects, and careful monitoring of blood levels is required.[10]

Prognosis

Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be a very severe illness and patients often require hospitalization. Because R. rickettsii infects the cells lining blood vessels throughout the body, severe manifestations of this disease may involve the respiratory system, central nervous system, gastrointestinal system, or kidneys.

Long-term health problems following acute Rocky Mountain spotted fever infection include partial paralysis of the lower extremities, gangrene requiring amputation of fingers, toes, or arms or legs, hearing loss, loss of bowel or bladder control, movement disorders, and language disorders. These complications are most frequent in persons recovering from severe, life-threatening disease, often following lengthy hospitalizations.

Epidemiology

There are between 500 and 2500 cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever reported in the United States per year,[22] and in only about 20% can the tick be found.

Host factors associated with severe or fatal Rocky Mountain spotted fever include advanced age, male sex, African or Caribbean background, chronic alcohol abuse, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. Deficiency of G6PD is a genetic condition affecting about 12 percent of the Afro-American male population. Deficiency in this enzyme is associated with a high proportion of severe cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever.[23] This is a rare clinical complication that is often fatal within five days of the onset of the disease.

In the early 1940s, outbreaks were described in the Mexican states of Sinaloa, Sonora, Durango, and Coahuila driven by dogs and Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato, the brown dog tick.[7] Over the ensuing 100 years case fatality rates were 30%–80%. In 2015, there was an abrupt rise in Sonora cases with 80 fatal cases. From 2003 to 2016, cases increased to 1394 with 247 deaths.[7]

History

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (or "black measles" because of its characteristic rash) was recognized in the early 1800s, and in the last 10 years of the 1800s (1890–1900) it became very common, especially in the Bitterroot Valley of Montana. The disease was originally noted to be concentrated on the west-side of the Bitterroot river.[24] Though it would be decades before scientists discovered the tick as the carrier of the disease, in as early as 1866, Doctor John B. Buker (establishing a practice in Missoula, MT) noticed a tick embedded in the skin of one of his patients. His notes were later studied as part of later research.[25]

In 1901, Dr. A. F. Longeway was appointed to solve "the black measles problem" in Montana. He in turn enlisted his friend, Dr. Earl Strain to help him. Strain suspected that the illness was from ticks. In 1906, Howard T. Ricketts, a pathologist recruited from the University of Chicago, was the first to establish the identity of the infectious organism (the organism smaller than a bacterium and larger than a virus) that causes this disease. He and others characterized the basic epidemiological features of the disease, including the role of tick vectors. Their studies found that Rocky Mountain spotted fever is caused by Rickettsia rickettsii, named in Howard Ricketts honor. Ricketts died of typhus (another rickettsial disease) in Mexico in 1910, shortly after completing his studies on Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Prior to 1922, Doctors McCray and McClintic both died while doing research on Rocky Mountain spotted fever, as did an aide of Noguchi Hideyo at the Rockefeller Institute. McCalla and Brerton also did early research into Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Research began in 1922 in western Montana, in the Bitterroot Valley around Hamilton, Montana, after the Governor's daughter and his son-in-law died of the fever. However, prior to that, in 1917, Dr. Lumford Fricks introduced herds of sheep into the Bitterroot Valley. His hypothesis was that the sheep would eat the tall grasses where ticks lived and bred.[26] Past Assistant Surgeon R.R. Spencer of the Hygienic Laboratory of the U.S. Public Health Service was ordered to the region, and he led a research team at an abandoned schoolhouse through about 1924.[27][28] Spencer was assisted by R. R. Parker, Bill Gettinger, Henry Cowan, Henry Greenup, Elmer Greenup, Gene Hughes, Salsbury, Kerlee, and others, of whom Gettinger, Cowan and Kerlee died of Rocky Mountain spotted fever.[28] Through a series of discoveries, the team found that a previous blood meal was necessary to make the tick deadly to its hosts, as well as other facets of the disease.[28] On May 19, 1924, Spencer put a large dose of mashed wood ticks, from lot 2351B, and some weak carbolic acid into his arm by injection. This vaccine worked, and for some years after it was used by people in that region to convert the illness from one with high fatality rate (albeit low incidence) to one that could be either prevented entirely (for many of them) or modified to a non-deadly form (for the rest).[28] Today there is no commercially available vaccine for RMSF[21] because, unlike in the 1920s when Spencer and colleagues developed one, antibiotics are now available to treat the disease, so prevention by vaccination is no longer the sole defense against likely death.

Much of the early research was conducted at Rocky Mountain Laboratories[29][30] a part of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The schoolhouse laboratory of 1922-1924, filled with ticks in various phases of the life cycle, is identifiable in retrospect as a biohazard, although the team did not fully appreciate it at first. The deaths of Gettinger and Cowan, and the near death of the janitor's son, were the results of inadequate biocontainment, but in the 1920s, the elaborate biocontainment systems of today had not been invented yet.

Society

Research into this disease in Montana is a sub-plot of the 1937 film Green Light, starring Errol Flynn. Some of the researchers who perished are mentioned by name and their photographs are shown.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is a big part of the 1947 Republic Pictures movie Driftwood, starring Walter Brennan, James Bell, Dean Jagger, Natalie Wood, and Hobart Cavanaugh.

In December 2013, hockey player Shane Doan was diagnosed with Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and returned to play in January 2014.[31]

Other names

Some synonyms for Rocky Mountain spotted fever in other countries include “tick typhus,” “Tobia fever” (Colombia), “São Paulo fever” or “febre maculosa” (Brazil), and “fiebre manchada” (Mexico).

References

- Pedro-Pons, Agustín (1968). Patología y Clínica Médicas. 6 (3rd ed.). Barcelona: Salvat. p. 345. ISBN 978-84-345-1106-4.

- "Pathogen Safety Data Sheets: Infectious Substances – Rickettsia rickettsii". Government of Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada. 7 January 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Signs and Symptoms Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF)". CDC. 26 October 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Transmission and Epidemiology Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF)". CDC. 26 October 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Clinical and Laboratory Diagnosis Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF)". CDC. 26 October 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Epidemiology and Statistics Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF)". CDC. 26 October 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Álvarez-Hernández Gerardo, Felipe González Roldán Jesús, Saúl Hernández Milan Néstor, Lash R Ryan, Barton Behravesh Casey, Paddock Christopher D (2017). "Rocky Mountain spotted fever in Mexico: past, present, and future". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 17 (6): e189–e196. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30173-1. PMID 28365226.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Treatment Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF)". CDC. 26 October 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF)". CDC. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Koyfman, Alex; Long, Brit; Gottlieb, Michael (2018-07-01). "The Evaluation and Management of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever in the Emergency Department: a Review of the Literature". Journal of Emergency Medicine. 55 (1): 42–50. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.02.043. ISSN 0736-4679. PMID 29685474.

- Biggs, Holly M. (2016). "Diagnosis and Management of Tickborne Rickettsial Diseases: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Other Spotted Fever Group Rickettsioses, Ehrlichioses, and Anaplasmosis — United States". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 65 (2): 1–44. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6502a1. ISSN 1057-5987. PMID 27172113.

- Saraiva DG, Soares HS, Soares JF, Labruna MB (2014). "Feeding period required by Amblyomma aureolatum ticks for transmission of Rickettsia rickettsii to vertebrate hosts". Emerg Infect Dis. 20 (9): 1504–10. doi:10.3201/eid2009.140189. PMC 4178383. PMID 25148391.

- Nava, S.; Beati, L.; Labruna, M. B.; Cáceres, A. G.; Mangold, A. J.; Guglielmone, A. A. (2014). "Reassessment of the taxonomic status of Amblyomma cajennense (Fabricius, 1787) with the description of three new species, Amblyomma tonelliae n. sp., Amblyomma interandinum n. sp. and Amblyomma patinoi n. sp., and reinstatement of Amblyomma mixtum Koch, 1844, and Amblyomma sculptum Berlese, 1888 (Ixodida: Ixodidae)". Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases. 5 (3): 252–76. doi:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.11.004. PMID 24556273.

- "Tickborne Rickettsial Diseases". Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. Centers for Disease Control. 2018-10-26.

- Dantas-Torres, Filipe (2007). "Rocky Mountain spotted fever". The Lancet Infectious Diseases (Submitted manuscript). 7 (11): 724–732. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(07)70261-x. hdl:2452/113243. PMC 1607456. PMID 698647.

- Chan, Yvonne; Cardwell, Marissa; Hermanas, Timothy; Uchiyama, Tsuneo; Martinez, Juan (April 2009). "Rickettsial Outer-Membrane Protein B (rOmpB) Mediates Bacterial Invasion through Ku70 in an Actin, c-Cbl, Clathrin and Caveolin 2-Dependent Manner". Cellular Microbiology. 11 (4): 629–644. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01279.x. PMC 2773465. PMID 19134120.

- Walker, David (2007). "Rickettsiae and Rickettsial Infections: The Current State of Knowledge". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 45: S39–S44. doi:10.1086/518145. PMID 17582568.

- Noriea, Nicholas; Clark, Tina; Hackstadt, Ted (2015). "Targeted Knockout of the Rickettsia rickettsii OmpA Surface Antigen Does Not Diminish Virulence in a Mammalian Model System". Journal of Molecular Biology. 6 (2): e00323–15. doi:10.1128/mBio.00323-15. PMC 4453529. PMID 25827414.

- Woods CR (April 2013). "Rocky Mountain spotted fever in children". Pediatr Clin North Am. 60 (2): 455–70. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2012.12.001. PMID 23481111.

- Gammons M, Salam G (August 2002). "Tick removal". Am Fam Physician. 66 (4): 643–5. PMID 12201558.

- "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018-10-26.

- "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever – Statistics and Epidemiology". Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- Walker, D. H.; Hawkins, H. K.; Hudson, P. (March 1983). "Fulminant Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Its pathologic characteristics associated with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 107 (3): 121–125. ISSN 0003-9985. PMID 6687526.

- "History of Rocky Mountain Labs (RML) | NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases". www.niaid.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- Bleed, Blister and Purge: A History of Medicine on the American Frontier by Volney Steele, M.D.ISBN 0-87842-505-5

- Steele, Volney, M.D. Bleed, Blister and Purge: A History of Medicine on the American Frontier. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, Montana. 2005.

- Spencer R.R.; Parker R.R. (1930). Studies on Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Hygienic Laboratory Bulletin. 154. Washington: U.S. G.P.O. OCLC 16141346.

- de Kruif, Paul (1932). "Ch. 4 Spencer: In the Happy Valley". Men Against Death. New York: Harcourt, Brace. OCLC 11210642.

- "Rocky Mountain Laboratories Official Site". Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- "Overview". Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. Centers for Disease Control. 2018-10-26.

- "'Yotes Notes: Doctors Give Doan OK to Play".

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rocky Mountain spotted fever. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Ixodidae. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Rickettsia. |

- "Rocky Mountain spotted fever". Centers for Disease Control. 2018-10-26.