Snowdon Mountain Railway

The Snowdon Mountain Railway (SMR; Welsh: Rheilffordd yr Wyddfa) is a narrow gauge rack and pinion mountain railway in Gwynedd, north-west Wales. It is a tourist railway that travels for 4.7 miles (7.6 km) from Llanberis to the summit of Snowdon, the highest peak in Wales.[4]

| Snowdon Mountain Railway Rheilffordd yr Wyddfa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

.jpg.webp) Snowdon Mountain Railway in June 2012 | |||

| Overview | |||

| Owner | Heritage Great Britain[1] | ||

| Locale | Gwynedd | ||

| Termini | Llanberis Snowdon/Yr Wyddfa | ||

| Service | |||

| Type | Rack and pinion mountain railway | ||

| Operator(s) | Heritage Great Britain | ||

| History | |||

| Opened | 6 April 1896 | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 4 mi 55 ch (7.5 km)[2] | ||

| Number of tracks | Single track with passing loops | ||

| Rack system | Abt[3] | ||

| Track gauge | 800 mm (2 ft 7 1⁄2 in) | ||

| |||

Snowdon Mountain Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The SMR is the only public rack and pinion railway in the United Kingdom,[5] and after more than 100 years of operation it remains a popular tourist attraction, carrying more than 140,000 passengers annually.[6] The line is owned and operated by Heritage Great Britain,[7] operators of several other tourist attractions in the United Kingdom.

The railway is operated in some of the harshest weather conditions in Britain, with services curtailed from reaching the summit in bad weather and remaining closed during the winter from November to mid-March. Single carriage trains are pushed up the mountain by either steam locomotives or diesel locomotives. It has also previously used diesel railcars as multiple units. The railway has two new hybrid locomotives on order, for introduction at the start of the 2020 season.

The SMR was the inspiration for the fictional Culdee Fell Railway, appearing in the book Mountain Engines, part of The Railway Series written by Reverend W. Awdry.

History

Construction

The idea of a railway to the summit of Snowdon was first proposed in 1869, when Llanberis was linked to Caernarfon by the London & North Western Railway. In 1871 a Bill was put before Parliament, applying for powers of compulsory purchase for a railway to the summit, but it was opposed by the local landowner, Mr Assheton-Smith of the Vaynol Estate, who thought that a railway would spoil the scenery.[8]:12–13

For two decades nothing happened, and Assheton-Smith remained opposed to any plans. However, in 1893 the Rhyd Ddu terminus of the North Wales Narrow Gauge Railways was renamed Snowdon, attracting many of the tourists who previously visited Llanberis and affecting the livelihoods of the accommodation providers who were Assheton-Smith tenants.[9]

After much persuasion Assheton-Smith ultimately gave his assent to the construction of a railway to the summit,[3] and though still the principal landowner in the area, he was not a major influence in the company. However, no Act of Parliament was now required, as the line was built entirely on private land obtained by the company, without any need for the power of compulsory purchase. This was unusual for a passenger-carrying railway, and also meant that the railway did not come under the jurisdiction of the Board of Trade.

The railway was constructed between December 1894, when the first sod was cut by Enid Assheton-Smith (after whom locomotive No. 2 was named), and February 1896, at a total cost of £63,800 (equivalent to £7,437,000 in 2019).[10] The engineers for the railway were Sir Douglas Fox and Mr Andrew Fox of London, and the contractors were Messrs Holme and King of Liverpool.[11]

By April 1895 the earthworks were 50% complete, a sign of the effort put into the construction work as much as of the lack of major earthworks along much of the route.

All tracklaying had to start from one end of the line, to ensure the rack was correctly aligned; so although the first locomotives were delivered in July 1895 very little track was laid until August, when the two large viaducts between Llanberis and Waterfall were completed. Progress up the mountain was then quite rapid, with the locomotives being used to move materials as required. Considering the exposed location and possible effects of bad weather, it is surprising that the first train reached the summit in January 1896. As the fencing and signals were not then ready, the opening was set for Easter.

The line was opened at Easter 1896. In anticipation of this, Colonel Sir Francis Marindin from the Board of Trade made an unofficial inspection of the line on Friday 27 March. This included a demonstration of the automatic brakes. He declared himself satisfied with the line, but recommended that the wind speed be monitored and recorded, and trains stopped when the wind was too strong.

On Saturday 4 April a train was run by the contractor consisting of a locomotive and two coaches. On the final section, the ascending train hit a boulder that had fallen from the side of a cutting and several wheels were derailed. The workmen on the train were able to rerail the carriage and the train continued.[12]

Opening day accident

The railway was officially opened on Monday 6 April 1896, and two trains were dispatched to the summit. On the first return trip down the mountain, possibly due to the weight of the train, locomotive No. 1 Ladas with two carriages lost the rack and ran out of control. The locomotive derailed and fell down the mountain. A passenger died from loss of blood after jumping from the carriage.[13] After a miscommunication the second downward train hit the carriages of the first, with no fatalities.

An inquiry concluded that the accident had been triggered by post-construction settlement,[14] compounded by excess speed due to the weight of the train. As a result of the inquiry's recommendations the maximum allowed train weight was reduced to the equivalent of 1½ carriages, leading to lighter carriages being bought and used on two-carriage trains. A gripper system was also installed on the rack railway.

Prewar

The railway reopened to Hebron on Saturday 26 September 1896.[15] On 9 April 1897 the line re-opened to Clogwyn.[16] By June the trains were again reaching the summit. This time there were no incidents and the train service continued.

On 30 July 1906 a wagon broke loose and ran into a train, injuring one passenger, the driver and guard. Traffic was suspended for several hours.[17]

In 1910 there were reports of vandalism on the line. A man named William Morris Griffiths who had climbed Snowdon to see the sunrise, placed a stone on the rail and sitting on it, slid down the track at speed. Someone put a boulder on the line behind him and pushed it down, and it struck Griffiths in the back, he somersaulted off the line and died a few hours later. The manager of the railway also reported that crowds of visitors were breaking down fences, pulling up gradient posts, throwing down wires and interfering with the railway bed.[18]

In 1936 it was reported that the railway carried 30,000 people to the summit during the season.[19]

Passengers were still carried during World War II. The Western Mail for 12 May 1943 reported that two trains per day would operate from Llanberis (at 1.15pm and 4.00pm) and people could still book to stay at the summit hotel.[20] However, this appears to have been just propaganda, as the summit was closed for military purposes from 1942 until the end of the war.

Postwar

Normal service resumed in 1946. The shortage of coal led to the railway attempting to burn old army boots as fuel.[21] The British Railways Llanberis–Caernarvon line closed to passengers in 1962. In 1983, the summit buildings were transferred to the ownership of Gwynedd County Council. A share issue was made in 1985, primarily to raise money to purchase the first two diesel locomotives. Between 1986 and 1992 the railway company was involved with the airfield and aviation museum in Caernarvon.

Centenary

As part of the centenary celebrations the railway held an enthusiasts' weekend in September 1996. This was one of the few occasions when the public were allowed to visit the railway's workshops. Scrap pinion rings were also sold as (rather large) souvenirs. From this time the locomotives were painted in differing liveries, but by 2005 this practice had ended.

Summit building project

In 2006 the Snowdon summit cafe was demolished and construction of a new visitor centre was started. While this construction was taking place passenger trains terminated at Clogwyn, but the line and a works train was still used to transport workers and materials to the project. On some days, however, the train could not reach the summit and the workers had to walk down to Rocky Valley.[22] The new building, Hafod Eryri (loosely translated from Welsh as "high summer residence of Snowdonia"),[23] was officially opened by First Minister Rhodri Morgan on 12 June 2009.[22]

Rescue work

In 2015, after the coastguard rescue helicopter was unable to reach the summit, the railway was used to carry mountain rescue teams to the summit of Snowdon to rescue a 17-year-old girl who had collapsed due to an asthma attack while sheltering from wind gusting up to 70 miles per hour (110 km/h). The railway was then used to carry the girl and rescuers to the foot of the mountain, where she was transferred to an ambulance.[24]

Route

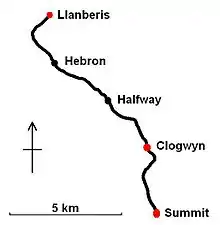

The lowland terminus is Llanberis station, at the side of the main road. The railway is a single track line with passing loops. It is 4 miles 1,188 yards (7.524 km) long, with an average gradient of 1 in 7.86 (12.7%). The steepest gradient is 1 in 5.5 (18.2%), and this occurs in a number of places. The railway rises a total of 3,140 feet (960 m), from 353 feet (108 m) above sea level at Llanberis to 3,493 feet (1,065 m) at Summit station.

- Llanberis station 53.1163°N 4.1195°W (353 ft (108 m)) has two platforms. The first stretch of line is uphill at 1 in 50, steep for a main line but shallow compared with the 1 in 6 incline that begins shortly afterwards.

- Waterfall station 53.1111°N 4.1266°W is now closed, but the station building remains. It was built to allow visitors to use the train to travel to a spectacular waterfall close to the line. A short distance from Waterfall station is a bridge over the river and a gate. This marks the start of the mountain.

- Hebron station 53.1046°N 4.1179°W (1,069 ft (326 m)) is named after the nearby 'Hebron' Chapel. It had originally been hoped that agricultural traffic could be carried to and from this station.

- Halfway station 53.0956°N 4.0960°W (1,641 ft (500 m)) as the name suggests, halfway along the line and close to the 'Halfway House' on the nearby footpath. A short distance above the station is a path that leads down to the Halfway House cafe.

- Rocky Valley Halt 53.0889°N 4.0838°W (2,330 ft (710 m)) consists of a narrow platform sheltered by a rocky outcrop to the east. Immediately beyond the platform the line joins the exposed ridge on which it runs for about one-half mile (0.8 km).

- Clogwyn 53.0841°N 4.0803°W (2,556 ft (779 m)) is located on the exposed ridge and overlooks the Llanberis Pass and the Clogwyn Du'r Arddu cliffs, a popular climbing spot.

- Summit 53.0680°N 4.0783°W (3,493 ft (1,065 m)) is only 68 feet (21 metres) below the summit, which is at 3,560 ft (1,085 m). The station has two platforms that link directly to the summit building and to a path to the summit.

Operation

The Llanberis complex also houses the company offices, locomotive shed and workshop building. The forecourt has recently been changed from a visitor car park into a café and picnic area.

Train control

Traffic and train movements are controlled from Llanberis: communication between Llanberis, Clogwyn and the Summit, as well as to trains' guards, is by two-way radio.

The line has three passing loops, around 15 minutes travelling time apart. Going up the mountain, these are at Hebron, Halfway and Clogwyn stations. The operation of the Hebron and Halfway loops was converted to semi-automatic operation in the early 1990s. The Clogwyn loop is still staffed and retains the original mechanical point levers. Waterfall station had a siding but never a loop, and has been closed for many years.

All three passing loop tracks are on the southwest side of the main running line – this is in general the downhill side, where the mountain slopes away from the line. This means that, if required, the line could be easily be converted to double track without the need to cut into the rock face to widen the formation.

Including stops at the passing loops, the train takes an hour to climb to the summit and an hour to descend again, at an average speed of around 5 mph (8 km/h).

Passenger trains normally run from Llanberis to the Summit. The wind speed is measured at Clogwyn Station and used to determine if trains can continue to the summit. Trains terminate at Rocky Valley Halt when the weather is too bad to allow them to proceed safely to the summit.

It is possible for two trains to run together on sight, which involves the second train following shortly (more than two minutes but less than five) after the first, and keeping a safe distance throughout the journey. This is known as a "doubler". All platforms and passing loops are long enough to accommodate two trains.

The two Llanberis platforms are dedicated, one for arrivals and the other for departures. Arriving trains empty of passengers then shunt to the other platform. At the Summit station arriving trains generally alternate between the two platforms.

When steam and diesel trains run together, it is normal for the diesel to lead up the mountain. This allows the steam train to enter the departure platform and load at its leisure, while the diesel moves across from the arrival platform from a quick turn-around.

Locomotives spend the whole day with the same carriage. Any locomotive can work with any carriage, although carriage No. 10 (the most modern) until 2012 usually ran with a diesel locomotive.

In 2013 four new carriages, which seat 74 passengers instead of 56 (as in the old ones), entered service. They work together with the four diesel locomotives and thus form four identical trains.[25]

Passenger traffic

Most passengers are tourists, and travel on a return trip, which typically involves being booked on a specific train for a round trip to the summit, with a half-hour break at the top. Down-only journeys can also be made from the Summit and Clogwyn, on a standby basis.

Trains depart from Llanberis station at regular intervals, up to every 30 minutes at busy times, although trains are only run if a minimum number of tickets have been sold. During the summer when the weather is favourable, most trains are sold out. Passengers are not allowed to leave or join trains at Halfway or Hebron, but they may join down trains at Clogwyn Station if there is space.

Other traffic

The first train of the day is the works train. This carries staff and supplies, including drinking water and fuel for the generator, to the summit. It also stops at Halfway station to drop off supplies for the cafe. It returns mid-morning with the previous day's rubbish from the summit. The train also carries the permanent way maintenance gang to where they are working. Upon its return to Llanberis, the locomotive from this train (always now a diesel) goes straight into service with a passenger train.

Steam versus diesel

For steam-hauled trains, the Llanberis shunt movement includes a trip to the water crane and coaling stage outside the locomotive shed. At Halfway Station steam locomotives also take water from a water crane, fed from a large tank located just above the station. For emergency use another large water tank is situated near Clogwyn Station which can feed two water cranes.

The diesel locomotives are used on the normal trains, with the steam locomotives being used on higher priced Heritage Steam trains.[26] On arrival at Llanberis, diesel-hauled trains run directly from the arrival platform to the departure platform, load and depart at the scheduled time. Steam-hauled trains take at least half an hour to transfer from the arrival to the departure platform, thus making no more than one trip every three hours.

The use of diesel locomotives therefore allows more trains to be run with the same number of carriages. By using diesels, the reduction in costs for both operating trains over the line and having them standing between infrequent runs has allowed the operating season to be extended considerably.

It is stated by the management that the vast majority of passengers do not care whether the trains are powered by steam or diesel locomotives. In the late 1980s comparative figures for the diesels against steam locomotives made it clear that they made economic sense.

From 1987 Steam Diesel Round trip fuel costs £51.00 (equivalent to £144.51 in 2019)[10] £3.05 (equivalent to £8.64 in 2019)[10] Locomotive crew 2 1 Round trips per day 3 4 Daily maintenance (hours) 1 1⁄2 1⁄2

- Note: these figures are taken from a talk given by a member of the design team. It is assumed that the fuel costs include the cost of fuel for lighting up a steam locomotive, or keeping the fire in overnight, as well as the fuel for a single round trip. For a diesel locomotive, preparation consists only of starting the engine and leaving it to run until sufficient air pressure has been created.

Safety

Train formation

For safety, train formations consist of one locomotive pushing a single carriage up the mountain and leading it down again while the locomotive brakes allow a controlled descent. (On opening, the usual practice was to have a locomotive pushing two coaches; this was changed in 1923.)[8]:94 The carriage is not coupled to the locomotive, as gravity keeps the two in contact. The track is always uphill from the lower end to the top end - it is never even near level

An electric cable is run between the locomotive and the carriage, which enables a buzzer to be used to signal between the driver and the guard. The cable is designed to pull free if the locomotive and carriage separate. Not being coupled prevents a carriage being dragged down the mountain if a locomotive derailed, as happened in the opening day accident.

Couplings are used during shunting operations as the yard is on level ground (see photograph of No. 6 at Llanberis). It was originally intended that each steam locomotive push two carriages to the summit, but this has not been normal practice since 1914.

Gripper rail

Following an accident in 1896, most of the line was fitted with 'gripper rails'. These are fixed to either side of the centre toothed rack rail and are of an inverted 'L' cross section. A 'gripper' is fitted to each locomotive, which fits around the gripper rails and holds the locomotive to the rails and prevents the pinion coming free from the rack. Although no other Abt rack railways use a gripper system,[27] other rack systems do.

The gripper rails are not fitted in the top and bottom stations, around Llanberis yard, on any pointwork, nor on the less steep lengths of railway just out of Llanberis and near Waterfall. At the beginning of the sections of gripper rail, the ends are staggered and chamfered to help guide the gripper into place.

If a broken rack bar lifts under a locomotive, it can strike the gripper and jam under the train. In such an incident, the gripper has to be cut away in order to rescue the train.

A mechanical failure in 1987 (a broken rod on the locomotive)[28] could have caused a repeat of the 1896 accident, but the gripper system worked and held the train on the rails; the rails were, however, lifted off the ground by the locomotive.

Braking systems

All braking is done using the rack and pinion system. Every locomotive and carriage has a pinion, allowing each vehicle to brake itself.

Locomotives and carriages each have a hand brake which operates brake blocks that clasp drums on either side of the pinions. On the steam locomotives the hand brake is applied manually; two identical hand brake levers are fitted, one for the driver and one for the fireman. On the diesel locomotives, the hand brake is applied by a powerful spring and held off by a hydraulic system.

In normal operation for locomotive/carriage trains, on descending and level running, the train is normally braked (service braking) using the locomotive. This uses compression braking – the energy is absorbed by using the cylinders as pumps, then dumping the pressure, similar to a Jake brake – on steam locomotives, hydraulic braking on the diesel locomotives. The diesel-electric railcars were service braked using hydraulic brakes and dynamic braking, during which power was dissipated in roof-mounted resistors, creating a distinct heat shimmer when the vehicles were descending and shortly afterwards. The hand brakes are used to bring a train to a complete stand from low speed, and as a parking brake.

A train or carriage could be brought down the mountain using the hand brake, but this would be an emergency usage, as it would cause significant wear and heat damage.

For increased safety, each vehicle is also fitted with an automatic brake that is triggered if the vehicle exceeds a specific speed, such as a carriage running away or a locomotive engine failure. This system slows the train down using the same brake blocks and drums as the hand brake. The running speed at which the automatic brake comes on is lower for the carriages than the locomotive, to prevent a carriage running into a stationary locomotive further down the track.

The automatic brake works by monitoring the speed using a centrifugal governor connected by gears to a large toothed gear mounted on the pinion axle next to the wheel (i.e. it is not the pinion gear). When the set speed is exceeded a lever on the governor hits a lever on a brake valve, and the brakes operate. The automatic brake can only be released after the train has come to a stop, and the driver has to leave the locomotive to reset the system. On the steam locomotives, steam is applied to a small brake cylinder that acts on the driver's side brakes. On the carriages, the automatic brake is an air brake. On the diesel locomotives, a hydraulic cylinder is used.

It is vitally important that all braking is done in a controlled manner, as any sudden shocks impose very high loads on the rack rail and pinion wheels, and can cause damage.

Rack railway

The line is built to 800 mm gauge (2 ft 7 1⁄2 in gauge), a gauge it has in common with several other rack railways in Switzerland. The rails are fastened to steel sleepers.

The line uses the Abt rack system devised by Roman Abt, a Swiss locomotive engineer. The system comprises a length of toothed rail (the rack) between the running rails which meshes with a toothed wheel (the pinion) mounted on each rail vehicle's driving axle. The traditional logo for the railway is a pinion ring engaged on a rack bar. At the stations and passing loops, the real items are mounted on steel frames.

The entire railway is fitted with the rack rail. On sidings and around the yard at Llanberis it comprises a single rack bar, but on the running line, and through all the loops up the mountain, two rack bars are used, mounted side by side with their teeth staggered by half a pitch. This is one of the major features of the Abt system, and helps to reduce the shock of the pinions running along the rack. It also ensures the pinion maintains continuous contact with the rack. The joints between rack bars are also staggered and align with the sleepers – each sleeper supports the rack rail as well as the running rails.

The locomotive pinions engage the rack and provide all the traction and braking effort; the wheels are free to revolve on the drive axles, to allow for the inevitable difference between the wheel radius and the effective radius of the pinion. The wheels serve only to support and guide the vehicle; if the pinion were missing, handbrake on and locomotive crank locked, the vehicle would still roll down the mountain. (The wheels are not capable of providing useful adhesion on such a gradient, so this is not the disadvantage it might seem.) The two driving axle pinions on a locomotive are mounted with a half a pitch difference between them. Combined with the half pitch difference in the two rack bars, this feature aims to make the transfer of power more continuous, and thus smooth the hauling of the train. In spite of this, the vehicles still suffer from very high levels of vibration.

The rack bars are machine cut from a special quality of steel: the profile is not symmetrical and the bars must be installed the right way round. Bars tend to fracture between the fixings. When spotted these breaks are marked and then supported with wedges until the bar can be replaced. The pinions consist of an outer ring that is easily replaced. This ring is mounted onto a centre disc, and springs between the two reduce shock loads and allow the small movement needed to accommodate joints and curves. The pinion rings have symmetrical teeth and are turned round to double their working life.

Rolling stock

The company has owned a total of eight steam locomotives, five diesel locomotives and three diesel railcars.

History

When the railway was being planned, only the Swiss had significant experience in building rack locomotives, so it was they who won the contract to build the engines for the line. In comparison with some Swiss railways the line is not very steep, and this is reflected in the design of the engines, which are all classified 0-4-2T. The boilers of the locomotives are set at an angle of 9°, to keep the water level over the tubes when the locomotive is ascending the mountain.[8]:101

Built specially for the line in 1895 and 1896, Nos. 1 to 5 were manufactured by the Swiss Locomotive and Machine Works of Winterthur. The first locomotives cost £1,525 (equivalent to £177,448 in 2019).[10] Nos. 1 to 3 were delivered before the line was open and used on construction work. On at least two occasions, trials have been made on oil burners on Nos. 1 to 5, the latest being on No. 2 in the late 1990s.

For most of the time, the railway's steam locomotives have burnt coal. The requirement for the locomotives to have a hot fire burning efficiently for a solid hour has led to problems when best Welsh steam coal has not been readily available. During 1978 Nos. 2 and 8 ran with oil burners. To hold the fuel oil, a tank was fitted to the roof of each locomotive. The tanks were thin and followed the profile of the roof. In 2000, No. 2 was again fitted with an oil burner in an attempt avoid the increasing problems of obtaining suitable coal.

In 1922–23 a further three locomotives were delivered, becoming Nos. 6 to 8. Although similar to the first engines in terms of size and power, they have a different design. Again all were built by Swiss Locomotive and Machine Works of Winterthur.

When the boilers of Nos. 7 and 8 needed replacing they were withdrawn from service in 1990 and 1992 respectively, but no new boilers were bought. This is probably due to the extra expense of superheaters, and to the reduced need for steam locomotives after the introduction of the diesels. Neither is likely to run in the foreseeable future.

The railway first thought of using a diesel locomotive in the early 1970s, when a small four-wheeled diesel-mechanical locomotive built by Ruston & Hornsby (their class 48DL) was bought second-hand from a quarry. It was intended to regauge it and use it as a yard shunter at Llanberis. It was sold to the Llanberis Lake Railway in 1978 without being regauged or used on the SMR. It would have been the railway's only locomotive without pinions, and as such would have been of limited use – it is doubtful if it would have had sufficient grip on the grease covered rails to shunt a dead steam locomotive. This locomotive has since been dismantled and scrapped.

It was the mid 1980s before any effort was made to obtain a diesel locomotive that could work trains up the line. Between 1986 and 1992, four diesel locomotives were bought from the Hunslet Engine Company of Leeds, to a design and specification jointly developed with the railway. These became Nos. 9 to 12. During the period between the building of No. 9 and No. 12 both the locomotive manufacturer and the diesel engine manufacturer changed their names, Hunslet becoming Hunslet-Barclay and Rolls-Royce diesel engines being sold to Perkins.

In 1995 three identical railcars built by HPE Tredegar (successor to Hugh Phillips Engineering) were delivered. These were designed to run as either two- or three-car multiple unit trains. When all three were coupled together, they were the maximum length of a train that could fit into the platforms and passing loops.

List of motive power

| No | Name | Built | Manu. no. | Type | Class | Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ladas | 1895 | 923 | Steam locomotive | 0-4-2RT | Scrapped | Named after Laura Alice Duff Assheton-Smith, wife of the major landowner in the area. It arrived at Llanberis in July 1895 and cost £1523.[8]:97 A race horse was also named Ladas and it is after the race horse that the LNER locomotive No. 2566 was named. This is the same Alice as the class of small Hunslet quarry engines. Destroyed in an accident on the railway's opening day and was broken up for spare parts. |

| 2 | Enid | 1895 | 924 | 0-4-2RT | Operational |  Named after Laura Alice's daughter, who cut the first sod in December 1894 in place of her mother, who was ill at the time. It arrived at Llanberis in August 1895 and cost £1,525.[8]:97 Enid is pronounced "Ennid". | |

| 3 | Wyddfa | 1895 | 925 | 0-4-2RT | Operational |  Arrived at Llanberis on 7 December 1895. Yr Wyddfa is Welsh for Snowdon | |

| 4 | Snowdon | 1896 | 988 | 0-4-2RT | Awaiting Overhaul | .jpg.webp) Named after the mountain itself | |

| 5 | Moel Siabod | 1896 | 989 | 0-4-2RT | Operational |  Named after a neighbouring mountain, Moel Siabod | |

| 6 | Padarn | 1922 | 2838 | 0-4-2RT | Operational | .jpg.webp) Named after a 6th-century saint, after whom the lower lake at Llanberis is also named. Originally named Sir Harmood after the chairman of the company, Sir John Sutherland Harmood-Banner, it was renamed Padarn in 1928.[8]:99 | |

| 7 | Ralph | 1923 | 2869 | 0-4-2RT | Withdrawn |  Dismantled and stored off-site. It is unlikely that this locomotive will be returned to service. Originally named Aylwin until October 1978 when it was renamed Ralph Sadler, later shortened to Ralph, after the company's consulting engineer between 1964 and 1977.[8]:99 Involved in a derailment in August 1987. | |

| 8 | Eryri | 1923 | 2870 | 0-4-2RT | Withdrawn | _No_8_'Eryri'_approaching_Summit_Station%252C_N_Wales_18.8.1992_(10196585034).jpg.webp) Dismantled and stored off-site. It is unlikely that this locomotive will be returned to service. Eryri is the Welsh name for Snowdonia. | |

| — | — | 1949 | Diesel locomotive | 0-4-0DM | Scrapped | Bought second-hand from a quarry in 1972 as a potential shunter. Sold unused to the Llanberis Lake Railway in 1978. Since been dismantled and scrapped. | |

| 9 | Ninian | 1986 | 0-4-0DH | Operational |  Ninian is named after the Chairman at the time the locomotive was delivered | ||

| 10 | Yeti | 1986 | 0-4-0DH | Operational | .jpg.webp) Named Yeti by local school children following a competition. It was seen as a most suitable name for a mountain creature. | ||

| 11 | Peris | 1991 | 0-4-0DH | Operational |  Named after the upper lake at Llanberis (Llyn Peris). According to the plate on the loco it was named after Saint Peris, a Christian missionary serving in the Llanberis area. | ||

| 12 | George | 1992 | 0-4-0DH | Operational | .jpg.webp) Named after George Thomas, 1st Viscount Tonypandy | ||

| 21 | — | 1995 | Diesel electric railcar | Scrapped | Withdrawn from use 2001, taken away for scrap July 2010 | ||

| 22 | — | 1995 | Scrapped |  Withdrawn from use 2003, taken away for scrap July 2010 | |||

| 23 | — | 1995 | Scrapped |

Steam locomotives No. 1 to No. 5

The boilers are inclined on the locomotives, to ensure that the boiler tubes and the firebox remain submerged when on the gradient, a standard practice on mountain railways – the locomotive always runs chimney-first up the mountain. The water gauges (gauge glasses) are mounted half at the centre on the locomotive so that the water level does not change with the gradient. One result of the boiler's angle is that the firehole door is at waist height, requiring the fireman to lift the coal some distance. The boiler is not superheated. Water is carried in tanks that run the full length of the boiler, but not all this water is for use in the boiler. The tanks are in fact divided into two sections, the smaller front section holding water that is used for cooling when the engine is running downhill. The drive to the wheels is through a series of levers that allow the pistons to have a longer stroke than the cranks. This is another common feature in mountain railways.

Steam locomotives No. 6 to No. 8

The boilers of these engines are fitted with superheaters, making them more efficient, and in place of a lever-type regulator they have a wheel that must be turned 2 1⁄4 times between closed and fully open. The drive from the cylinders and to the wheels again uses levers, but in a different pattern. The linkage is fitted within double frames at the front of the locomotive. This results in a locomotive that is far more rigid. The side tanks are arranged vertically just in front of the cab. No. 6 carries the same amount of water as the earlier engines, but Nos. 7 and 8 carry enough water to get to the top of the mountain without stopping, if required. There is no separate tank for cooling water as it is drawn from the boiler on these engines.

Diesel locomotives No. 9 to No. 12

The design specifically includes features for safety, reliability and appearance. In place of cardan shaft drives to the wheels, coupling rods were used to give people something to watch and engine covers were omitted to give a good view of the Rolls-Royce diesel engines. The full-length canopy above the engine covers not only adds to the distinctive outline but also supports the exhaust silencer. For added safety with only one man in the cab, a dead-man device is included, a pedal that when released triggers the braking system to bring the train safely to a halt. The turbocharged six-cylinder engine is rated at 238 kW (319 hp) and drives through a hydraulic transmission that has only one drive ratio. The result is a locomotive that accelerates quickly up to speed. All four locomotives were rebuilt in 2012–13 in readiness for the launch of the new "traditional diesel" service.

Railcars No. 21 to No. 23

The railcars were diesel-electric, using a standard industrial generator set mounted at the downhill end of each vehicle. This powered an induction motor through electronic controllers. The generators had a Cummins engine rated at 137 kW (184 hp) which was run at a constant 1800 rpm and produced 440 V AC at 60 Hz. Unlike any other train on the system, the driver sat at the front when climbing the mountain.

For safety reasons the railcars could not be run as single vehicles since they each had only one set of pinions. No. 21 had to be taken out of service by 2001 owing to problems with the speed control mechanism, and Nos. 22 and 23 were taken out of service in 2003 for the same reason. The railcars were finally taken away for scrap in July 2010.

New hybrid locomotives

On 13 August 2019, the railway announced that it had ordered two new battery-diesel hybrid locomotives from Clayton Equipment Ltd for introduction at the start of the railway's 2020 season. The intention is that the diesel generator on the new locomotives will be switched off on the downhill runs, with regenerative service braking used to recharge the battery to provide power for the next ascent. This method of operation means that the locomotives' engines, which will comply with EU Stage V emission standards, can be less powerful than those on the existing locomotives, thus providing maintenance and fuel savings, quieter operation, and lower emissions.[29][30]

It was announced in February 2020 that the new locomotives were due to enter passenger service in May 2020. However, the launch was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[31]

Passenger coaches

All passenger coaches were withdrawn from service at the end of the 2012 season. With the exception of Coach 10 (the latest built), their bodies were dismantled and the frames and bogies were stored off-site. The railway now operates two services, depending on the motive power:

Traditional diesel service

Garmendale Engineering Ltd[32] was commissioned to build four brand new coaches for the 2013 season which are used exclusively with the diesel locomotives. These coaches can transport 74 passengers. Three of the coaches have so far been named: Sir David Brailsford CBE, Bryn Terfel CBE and Katherine Jenkins OBE. The fourth coach was named by Dame Shirley Bassey on 17 May 2018.[33]

Heritage steam experience

A new body was built on the original frames and bogies of Coach 2 by Garmendale Engineering Ltd to resemble an original coach from 1895. Named the Snowdon Lily, the coach entered service in 2013. This coach only carries 34 passengers and has a central aisle. It is used exclusively with one of the operational steam locomotives and attracts a higher fare. The steam service proved successful and a second heritage coach was built, using the frames and bogies of Coach 5. The Snowdon Mountain Goat arrived at the railway on 15 April 2015 and entered service following running in trials.

Liveries

It is believed that the first livery for the locomotives was dark-red. In these early years the carriages were open-bodied and were probably a dark brown in colour.

During the 1950s and 1960s all the vehicles were upgraded. The carriages were converted to closed-body design and the locomotives had their wooden shutters and doors replaced with more weather-resistant metal ones. The livery at this point was changed to a more typical Welsh livery, the carriages being cream and crimson and the locomotives pea-green and red.

Until 1998 the diesels were an overall mid-green colour. It was decided that the warning colour on the coupling section would be striped red and white, with the crank axles an overall red colour. The diesels' colouring was later changed: Yeti, for example, adopted a red livery, and George a purple one. The warning colours also changed several times until around 2004, when all the diesels again received a green livery, with yellow and black warning colours.

Opening day accident

First train

The public opening was on Monday 6 April 1896. A train was run from Llanberis to the summit to check that no more boulders had come loose; it is thought the locomotive was No. 2 Enid. On its return to Llanberis, locomotive No. 1 Ladas departed with two carriages on the official first train. Shortly afterwards, No. 2 Enid departed with a second public train. All went well on the ascent, except that mist and cloud was covering the top of the mountain and extending down to about the level of Clogwyn Station.

At a little after noon, Ladas with the two carriages started back down the mountain. About one-half mile (0.8 km) above Clogwyn, where the line runs on a shelf formed across a steep drop, the locomotive jumped off the rack rail, losing all braking force and accelerating down the track. At first it remained on the running rail and the driver tried to apply the handbrake, but with no effect. Realising that the train was out of control, the driver and his fireman jumped from the footplate.

Ladas ran about 110 yards (100 m) after losing the rack rail before hitting a left-hand curve. Here it derailed and fell over the side of the mountain. The two carriages accelerated to a speed at which the automatic brakes were triggered (7–10 mph [11–16 km/h]). These brakes brought both carriages to a stand safely. One of the passengers, Ellis Griffith Roberts of Llanberis, on seeing the driver and fireman jump from the locomotive did likewise. Falling to the ground, he sustained a serious injury to his leg, which later had to be amputated, and he died.[34]

Second train

In derailing, locomotive No. 1 had broken the telegraph lines used to signal between stations. Some versions say that the wires had touched as they were hit and made a signal that was mistaken for the 'line clear' signal, while other versions say that so long a time had passed that the people at the summit assumed that the telegraph system had failed. Whichever is true, the other train left the summit on its descent.

In spite of the 5 mph (8 km/h) line speed and a man being sent back up the line to warn the second train, it did not stop before reaching the point where No.1 had lost the rack rail; exactly the same thing happened, with No. 2 losing the rack rail and accelerating out of control. This time, however, the line was blocked by the carriages of the first train; No. 2 hit these with some force, causing the carriages of the first train to drag their brakes and run away down the line, and causing the locomotive to drop back onto the rack rail and stop safely. The carriages from the first train rolled down the line to Clogwyn station, where they became derailed.

Locomotive No. 1 was recovered and taken back to Llanberis.[16]

Inquiry

It was revealed during the inquiry that the locomotive on a ballast train had lost the rack in January 1895 a little lower down the line. Details are not recorded, but it is likely that the locomotive dropped back onto the rack and was not badly damaged.

After hearing all the evidence, it was decided that the weather had caused a freeze–thaw action which had led to settlement in the ground. Another contributory factor was the construction work being carried out during poor weather, and then not being checked for settlement when the weather had improved. The settlement was sufficient to twist the tracks and reduce the contact between the rack (on the track) and the pinion (on the locomotive). The weight and speed of the train did the rest. The damage caused by the first derailment made the second almost inevitable.

Recommendations

The first recommendation was that the maximum load for the locomotives be reduced to the equivalent of 1 1⁄2 carriages. These led to a further carriage being bought that was smaller and lighter than the others. From then on, only this carriage was used, with one of the originals, for two-carriage trains.

The second recommendation was that a gripper system be installed (see Gripper rail). This required extra rails to be added to the rack rail and a mechanism to be fitted to the locomotives and carriages.

See also

References

- "Welcome to Heritage Great Britain PLC". heritagegb.co.uk. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- Yonge, Padgett & Szwenk 2013, Map 51G.

- "Snowdon Mountain Railway history". snowdonrailway.co.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Tourist Attractions in Snowdonia Wales – Visit Snowdon Mountain Railway!, archived from the original on 15 April 2003

- Snowdon Mountain Railway on AboutBritain.com

- "Evaluation of Tourism Attractor Destinations: interim report". GOV.WALES. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Heritage Great Britain plc

- Williams, Rol (1987). Heibio Hebron: The History of the Snowdon Mountain Railway. Mei Publications.

- Johnson, Peter (2010). An Illustrated History of the Snowdon Mountain Railway. Oxford Publishing Co.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Opening of the Snowdon Mountain Railway". Wrexham Advertiser. Wales. 11 April 1896. Retrieved 26 October 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Carradice, Phil (6 April 2011). "Disaster on the Snowdon Mountain Railway". BBC Blogs - Wales. BBC. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Narrow Gauge Pleasure has Changed". narrow-gauge-pleasure.co.uk. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- "The adjourned inquest". Wrexham Advertiser. Wales. 18 April 1896. Retrieved 26 October 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "It was formally announced on Saturday…". Sheffield Daily Telegraph. England. 29 September 1896. Retrieved 26 October 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Opening of the Snowdon Railway". North Wales Chronicle. England. 24 April 1897. Retrieved 26 October 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Accident on Snowdon Railway". Nottingham Evening Post. England. 1 August 1906. Retrieved 26 October 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Fatal slide on the Snowdon Railway". Aberdeen Journal. Scotland. 22 September 1910. Retrieved 26 October 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "More than 30,000 people…". The Scotsman. Scotland. 3 November 1936. Retrieved 26 October 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Snowdon Mountain Railway". Western Mail. England. 12 May 1943. Retrieved 26 October 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Heritage Great Britain invests £1.1million in new Hybrid Diesel locomotives for Snowdon Mountain Railway". Snowdon Mountain Railway. Heritage Attractions Limited. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

... when the service reopened in 1946 old army boots were burned in the boilers of the engines to help power the carriages due to a fuel shortage.

- "£8.4m Snowdon summit cafe opens". BBC News. 12 June 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- "Snowdon visitors' centre is named". BBC News. 13 December 2006. Retrieved 13 December 2006.

- "Snowdon Mountain Railway helps rescue teen from summit". BBC News. 7 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Snowdon Mountain Railway Train Track Information – Snowdon Mountain Railway". snowdonrailway.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- "Snowdon Mountain Railway Train Times & Prices – Llanberis – Snowdon Mountain Railway". snowdonrailway.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- "abt rack railway and technical information". Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- "The mountain railway's railcars". Snowdon – Wales' Highest Mountain. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- "Snowdon Mountain Railway orders battery-diesel locos". Railway Gazette. 13 August 2019. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- "Snowdon Mountain Railway Invests in Future With New Hybrid Diesel Locomotives". Rail Professional. 13 August 2019. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- Warrenger, Sam (7 February 2020). "Snowdon Mountain Railway is buying 'greener' hybrid trains". Sustainable Days Out. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- "Snowdon Mountain Railway - Six years later | Garmendale Engineering UK". 3 September 2019.

- "Snowdon Mountain Railway carriage to be named after legendary Welsh singer". Daily Post. 26 March 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "ACCIDENT ON THE SNOWDON RAILWAY.|1896-04-10|Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald and North and South Wales Independent - Welsh Newspapers". newspapers.library.wales.

Sources

- Yonge, John; Padgett, David; Szwenk, John (2013). Gerald Jacobs (ed.). British Rail Track Diagrams - Book 4: London Midland Region (3rd ed.). Bradford on Avon: Trackmaps. ISBN 978-0-9549866-7-4. OCLC 880581044.

Further reading

- Boyd, James I.C. (1990) [1972]. Narrow Gauge Railways in North Caernarvonshire, Volume 1: The West. Headington: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-85361-273-5. OCLC 650247345.

- Neale, Andrew (1991). Welsh Narrow Gauge Railways: From Old Picture Postcards. Brighton: Plateway Press. ISBN 1-871980-08-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Snowdon Mountain Railway. |