Sonnet 55

Sonnet 55 is one of the 154 sonnets published in 1609 by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is included in what is referred to as the Fair Youth sequence.

| Sonnet 55 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

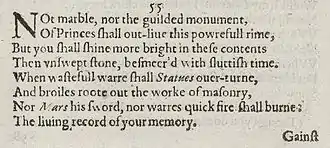

The first two stanzas of Sonnet 55 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Structure

Sonnet 55 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet contains three quatrains followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the form's typical rhyme scheme, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The fifth line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / When wasteful war shall statues overturn, (55.5)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Criticism

Sonnet 55 is interpreted as a poem in part about time and immortalization. The poet claims that his poem will outlast palaces and cities, and keep the young man's good qualities alive until the Last Judgement. The sonnet traces the progression of time, from the physical endeavours built by man (monuments, statues, masonry), as well as the primeval notion of warfare depicted through the image of "Mars his sword" and "war's quick fire", to the concept of the Last Judgment. The young man will survive all of these things through the verses of the speaker.[2]

John Crowe Ransom points out that there is a certain self-refuting aspect to the promises of immortality: for all the talk of causing the subject of the poems to live forever, the sonnets keep the young man mostly hidden. The claim that the poems will cause him to live eternally seem odd when the vocabulary used to describe the young man is so vague, with words such as "lovely", "sweet", "beauteous" and "fair". In this poem among the memorable descriptions of ruined monuments the reader only gets a glimpse of the young man in line 10 "pacing forth".[3]

These monuments, statues, and masonry reference both Horace's Odes and Ovid's Metamorphoses. Lars Engle argues that echoing the ancients, as the speaker does when he says "not marble, nor the gilded monuments / Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme;" further solidifies the speaker's claim about the longevity of the written word. However, while Horace and Ovid claim the immortality for themselves, the speaker in sonnet 55 bestows it on another. Engle also claims that this is not the first time Shakespeare references the self-aggrandizement of royals and rulers by saying that poetry will outlive them. He frequently mentions his own (political) unimportance, which could lead sonnet 55 to be read as a sort of revenge of the socially humble on their oppressors.[4]

While the first quatrain is referential and full of imagery, in the second quatrain Ernest Fontana focuses on the epithet "sluttish time". The Oxford English Dictionary gives "sluttish" two definitions: 1) dirty, careless, slovenly (which can refer to objects and persons of both sexes) and 2) lewd, morally loose, and whorish. According to Fontana, Shakespeare intended the second meaning, personifying and assigning gender to time, making the difference between the young man sonnets and the dark lady sonnets all the more obvious. Shakespeare had used the word "slut" nearly a year before he wrote sonnet 55 when he wrote Timon of Athens. In the play, Timon associates the word "slut" with "whore" and venereal disease. Associating "sluttish" with venereal disease makes Shakespeare's use of the word "besmeared" more specific. Fontana states: "The effect of time, personified as a whore, on the hypothetical stone statue of the young man, is identified in metaphor with the effect of syphilis on the body—the statue will be besmeared, that is, covered, with metaphoric blains, lesions, and scars." (Female) time destroys whereas the male voice of the sonnet is "generative and vivifying".[5]

Helen Vendler expands on the idea of "sluttish time" by examining how the speaker bestows grandeur on entities when they are connected to the beloved but mocks them and associates them with dirtiness when they're connected with something the speaker hates. She begins by addressing the "grand marble" and "gilded" statues and monuments; these are called this way when the speaker compares them to the verse immortalizing the beloved. However, when compared to "sluttish time" they are "unswept stone besmeared". The same technique occurs in the second quatrain. Battle occurs between mortal monuments of princes, conflict is crude and vulgar, "wasteful war" overturns unelaborated statues and "broils" root out masonry. Later in quatrain war becomes "war's quick fire" and "broils" become "Mars his sword". The war is suddenly grand and the foes are emboldened. The blatant contempt with which the speaker regards anything not having to do with the young man, or anything that works against the young man's immortality, raises the adoration of the young man by contrast alone.

Like the other critics, Vendler recognizes the theme of time in this sonnet. She expands on this by arguing that the sonnet revolves around the keyword "live". In quatrain 1, the focus is the word "outlive". In quatrain 2 it's "living"; in quatrain 3 "oblivious", and the couplet focuses on the word "live" itself. However, this raises the question of whether the young man actually continues to live bodily or if only his memory remains. There are references to being alive physically with active phrases like "you shall shine in these contents" and "'gainst death and all oblivious enmity / shall you pace forth", and also to living in memory: "the living record of your memory", and "your praise shall…find room…in the eyes of all posterity". Vendler argues that this question is answered by the couplet when it assigns "real" living to the day of the Last Judgment: "So till the judgment that your self arise / you live in this, and dwell in lovers' eyes."[6]

A possible contemporary reference

In the Folger Library, Robert Evans came across an epitaph that someone had written to the memory of Shakespeare. Evans could not find the verse recorded in various reference books. The epitaph was found on the last end page of a folio in the Folger collection. It is written in brown ink, in a secretary hand, which was a common 17th Century style of handwriting. It was written between two other epitaphs that are well known (including the one in the Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon where Shakespeare is buried). If it is authentic, it can be seen as another example indicating Shakespeare's regard among his contemporaries:

Heere Shakespeare lyes whome none but Death could Shake

and heere shall ly till judgement all awake;

when the last trumpet doth unclose his eyes

the wittiest poet in the world shall rise.

The lines of the verse echo lines from sonnet 55, which the unknown author may have been recalling. (“So, till the judgement that yourself arise, / You live in this, and dwell in lovers’ eyes.”)[7]

Interpretations

- Richard Briers, for the 2002 compilation album, When Love Speaks (EMI Classics)

References

- Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. ISBN 9781408017975. p. 221

- Kaula, David. "In War With Time: Temporal Perspectives in Shakespeare's Sonnets". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. Vol. 3, No. 1, The English Renaissance (Winter, 1963), pp. 45-57. JSTOR Database

- Ransom, John Crowe. The World’s Body. Charles Scribner's Son, New York, 1938. p. 287 ISBN 9780807101285

- Engle, Lars. "Afloat in Thick Deeps: Shakespeare's Sonnets on Certainty". PMLA, Vol. 104, No. 5 (Oct., 1989), pp. 832-843. JSTOR Database

- Fontana, E. "Shakespeare's Sonnet 55." The Explicator v. 45 (Spring 1987) p. 6-8. EBSCO Host Database

- Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997. Print.

- Evans, Robert. "Whome None but Death Could Shake: An Unreported Epitaph on Shakespeare". Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 39, No. 1, (Spring, 1988) p. 60. JSTOR Database

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png.webp)