Sorbs (tribe)

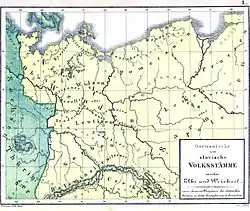

The Surbi, also known as Sorbs in modern historiography, was an Early Slavic tribe in Lower Lusatia, part of the Wends. In the 7th century, the tribe was part of Samo's Empire. The tribe is last mentioned in the late 10th century, but its descendants are an ethnic group of Sorbs.

History

7th century

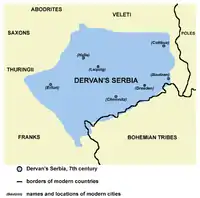

The oldest mention of the Surbi is from the Frankish 7th-century Chronicle of Fredegar. According to the source, they lived in the Saale-Elbe valley, having settled in the Thuringian part of Francia in the 6th century as vassals of Merovingian dynasty.[1][2] The Saale-Elbe line marked the approximate limit of Slavic westward migration.[3] Under the leadership of dux (duke) Dervan ("Dervanus dux gente Surbiorum que ex genere Sclavinorum"), they joined the Slavic tribal union of Samo, after Samo's decisive victory against Frankish King Dagobert I in 631.[1][2] Afterwards, these Slavic tribes continuously raided Thuringia.[1] The fate of the tribes after Samo's death and dissolution of the union in 658 is undetermined, but it is considered that subsequently returned to Frankish vassalage.[4]

8th century

In 782, the Sorbs, inhabiting the region between the Elbe and Saale, plundered Thuringia and Saxony.[5] Charlemagne sent Adalgis, Worad and Geilo into Saxony, aimed at attacking the Sorbs, however, they met with rebel Saxons who destroyed them.[6]

In 789, Charlemagne launched a campaign against the Wiltzi; after reaching the Elbe, he went further and successfully "subjected the Slavs".[7] His army also included the Slavic Sorbs and Obotrites, under Witzan.[7] The army reached Dragovit, who surrendered, followed by other Slavic magnates and chieftains who submitted to Charlemagne.[7]

9th century

The Surbi ended their partial vassalage to the Franks (the Carolingian Empire) and revolted, invading Austrasia; Charles the Younger launched a campaign against the Slavs in Bohemia in 805, killing their dux, Lecho, and then proceeded crossing the Saale with his army and killed rex (king) Melito (or "Miliduoch") of the Surbi, near modern-day Weißenfels, in 806.[8][9] The region was laid to waste, upon which the other Slavic chieftains submitted and gave hostages.[10][11] The rebellious Sorbs were compelled in 816 to renew their oaths of submission.[12]

In May 826, at a meeting at Ingelheim, Cedrag of the Obotrites and Tunglo of the Sorbs were accused of malpractices; they were ordered to appear in October, after Tunglo surrendered his son as hostage and was allowed to return home.[13] The Franks had, sometime before the 830s, established the Sorbian March, comprising eastern Thuringia, in easternmost East Francia.

In 839, the Saxons fought "the Sorabos, called Colodici" at Kesigesburg and won the battle, managing to kill their king Cimusclo (or "Czimislav"), with Kesigesburg and eleven forts being captured.[14] The Sorbs were forced to pay tribute and forfeited territory to the Franks.[14]

The mid-9th century Bavarian Geographer mentioned the Sorbs having 50 civitates.[15]

Svatopluk I of Moravia (r. 871–894) may have incorporated the Sorbs into Great Moravia.[3]

10th century

Between 932 and 963 the Sorbs lost their independence and were rapidly Germanized.[16] Henry the Fowler had subjected the Stodorane in 928, and in the following year imposed overlordship on the Obotrites and Veletians, and strengthened the grip on the Sorbs.[17] Bishop Boso of St. Emmeram (d. 970), a Slav-speaker, had considerable success in Christianizing the Sorbs.[18]

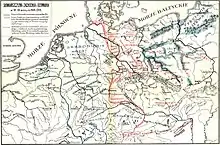

In the 10th century the region came under the influence of the Duchy of Saxony, starting with the 928 eastern campaigns of King Henry the Fowler, who conquered the Sorbs and Miltzenia (Upper Lusatia) by 932. Gero II, Margrave of the Saxon Eastern March, reconquered Lusatia the following year and, in 939, murdered 30 Sorbian princes during a feast. As a result, many Sorbian uprisings followed. The March of Lusatia was established in 965, remaining part of the Holy Roman Empire, while the adjacent Northern March was again lost in the Slavic uprising of 983. The later Upper Lusatian region of the Milceni lands up to the Silesian border at the Kwisa river at first was part of the Margraviate of Meissen under Margrave Eckard I. A reconstructed castle, at Raddusch in Lower Lusatia, is the sole physical remnant from this early period. These are the last mentions of the tribe.

Aftermath

During the reign of Boleslaw I of Poland in 1002–18, three Polish-German wars were waged which caused Lusatia to come under the domination of new rulers. In 1018, on the strength of peace in Bautzen, Lusatia became a part of Poland; however, it returned to German rule before 1031. At the same time the Kingdom of Poland raised claims to the Lusatian lands and upon the death of Emperor Otto III in 1002, Margrave Gero II lost Lusatia to the Polish Duke Boleslaw I, who took the region in his conquests. After the 1018 Peace of Bautzen, Lusatia became part of his territory, however Germans and Poles continued struggling for administration of the region. It was regained in a 1031 campaign by Emperor Conrad II in favour of the Saxon German rulers of the Meissen House of Wettin and the Ascanian margraves of Brandenburg, who purchased the March of (Lower) Lusatia in 1303. In 1367 the Brandenburg elector Otto V of Wittelsbach finally sold Lower Lusatia to Emperor and Bohemian King Charles IV and it was incorporated into the Kingdom of Bohemia.

From the 11th to the 15th century, agriculture in Lusatia developed and colonization by Frankish, Flemish and Saxon settlers intensified. In 1327 the first prohibitions on using Sorbian in Altenburg, Zwickau and Leipzig appeared.

White Serbs and Balkan Serbs

According to 10th-century De Administrando Imperio, the Serbs hailed from White Serbia (or "Boiki" i.e. Bohemia), "the neighbour of Francia", having settled in the Balkans during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (610–641) when the Serb Archon, one of two heirs, had led part of his tribe and claimed protection of the Emperor.[19] The archon was the progenitor of the first Serbian dynasty (the Vlastimirović), which ruled the Serbian Principality until c. 960.

According to German historian Ludwig Albrecht Gebhardi (1735–1802), the Serb Archon was most likely a son of Dervan.[20] This theory was supported by Miloš Milojević,[21] and Relja Novaković included the possibility that they were relatives in his work.[22]

References

- Sigfried J. de Laet; Joachim Herrmann (1 January 1996). History of Humanity: From the seventh century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. UNESCO. pp. 282–284. ISBN 978-92-3-102812-0.

- Gerald Stone (2015). Slav Outposts in Central European History: The Wends, Sorbs and Kashubs. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4725-9211-8.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 142.

- Saskia Pronk-Tiethoff (2013). The Germanic loanwords in Proto-Slavic. Rodopi. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-94-012-0984-7.

- Verbruggen 1997, p. 21.

- Jim Bradbury (2 August 2004). The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Routledge. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-1-134-59847-2.

- Leif Inge Ree Petersen (1 August 2013). Siege Warfare and Military Organization in the Successor States (400-800 AD): Byzantium, the West and Islam. BRILL. pp. 749–750. ISBN 978-90-04-25446-6.

- Vickers, Robert H. (1894). History of Bohemia. Chicago: C. H. Sergel Company. p. 48.

- Gerard Labuda (2002). Fragmenty dziejów Słowiańszczyzny zachodniej. PTPN. ISBN 978-83-7063-337-0.

806: „Et inde post non multos dies [imperator] Aquasgrani veniens Karlum filium suum in terram Sclavorum, qui dicuntur Sorabi, qui sedent super Albim fluvium, cum exercitu misit; in qua expeditione Miliduoch Sclavo- rum dux interf ectus

- Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 9, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization), 1880, p. 224

- Verbruggen 1997, pp. 314-315.

- Bury 2011, p. 900.

- Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 1880. p. 224.

- Janet Laughland Nelson (1 January 1991). The Annals of St-Bertin. Manchester University Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-0-7190-3425-1.

- Pierre Riche (1 January 1993). The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 110–. ISBN 0-8122-1342-4.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 147.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 144.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 90.

- Miloš Blagojević (2001). Državna uprava u srpskim srednjovekovnim zemljama. Službeni list SRJ. p. 14.

- Sava S. Vujić, Bogdan M. Basarić (1998). Severni Srbi (ne)zaboravljeni narod. Beograd. p. 40.

- Miloš S. Milojević (1872). Odlomci Istorije Srba i srpskih jugoslavenskih zemalja u Turskoj i Austriji. U državnoj štampariji. p. 1.

- Relja Novaković (1977). Odakle su Sebl dos̆il na Balkansko poluostrvo. Istorijski institut. p. 337.

Sources

- Secondary sources

- Vlasto, A. P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs Into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. CUP Archive. pp. 142–147. ISBN 978-0-521-07459-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verbruggen, J. F. (1997). The Art of Warfare in Western Europe During the Middle Ages: From the Eighth Century to 1340. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-570-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bury, J.B. (2011). The Cambridge Medieval History Series volumes 1-5. Plantagenet Publishing. GGKEY:G636GD76LW7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Primary sources

- Chronicle of Fredegar, 642

- Royal Frankish Annals, 829

- Bavarian Geographer, mid-9th-century

- Annales Fuldenses, 901