Tawfiq al-Hakim

Tawfiq al-Hakim or Tawfik el-Hakim (Arabic: توفيق الحكيم, ALA-LC: Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm; October 9, 1898 – July 26, 1987) was a prominent Egyptian writer and visionary. He is one of the pioneers of the Arabic novel and drama. The triumphs and failures that are represented by the reception of his enormous output of plays are emblematic of the issues that have confronted the Egyptian drama genre as it has endeavored to adapt its complex modes of communication to Egyptian society.[1]

Tawfīq el-Hakīm | |

|---|---|

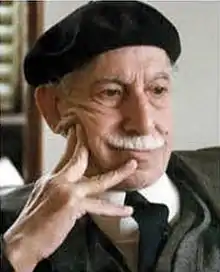

Undated photograph of Tawfiq al-Hakim | |

| Native name | توفيق الحكيم |

| Born | October 9, 1898 Alexandria, Khedivate of Egypt |

| Died | July 26, 1987 (aged 88) Cairo, Egypt |

| Occupation | Novelist, Playwright |

| Language | Arabic |

| Nationality | Egyptian |

| Notable works | The People of the Cave |

Early life

Tawfiq Ismail al-Hakim was born October 9, 1898, in Alexandria, Egypt, to an Egyptian father and Turkish mother.[2] His father, a wealthy and illustrious civil officer, worked as a judge in the judiciary in the village of al-Delnegat, in central Beheira province. His mother was the daughter of a retired Turkish officer. Tawfiq al-Hakim enrolled at the Damanhour primary school at the age of seven. He left primary school in 1915 and his father put him in a public school in the Beheira province, where Tawfiq al-Hakim finished secondary school. However, due to the lack of proper secondary schooling in the province, Tawfiq al-Hakim moved to Cairo with his uncles to continue his studies at Muhammad Ali secondary school.

After studying in Cairo, he moved to Paris, where he graduated in law and began preparing a PhD thesis at the Sorbonne. However, his attention turned increasingly to the Paris theatres and the Opera and, after three years in Paris, he abandoned his studies and returned to Egypt in 1928, full of ideas for transforming Egyptian theatre.

Egyptian drama before Tawfiq al-Hakim

The cause of 'serious' drama, at least in its textual form, was in the process of being given a boost by one of the Egypt's greatest littérateurs, Ahmed Shawqi, "Prince of Poets," who during his latter years penned a number of verse dramas with themes culled from Egyptian and Islamic history; these included Masraa' Kliyubatra (The Death of Cleopatra, 1929), Majnun Layla (Driven mad by Layla, 1931), Amirat el-Andalus (The Andalusian Princess, 1932), and Ali Bey al-Kebir (an 18th-century ruler of Egypt), a play originally written in 1893 and later revised. However, between the popular traditions of farcical comedy and melodrama and the performance of translated versions of European dramatic masterpieces, there still remained a void within which an indigenous tradition of serious drama could develop.and the teez of anything

War-time political writings

During WWII, al-Hakim published many articles against Nazism and Fascism.[3] The articles portrayed Hitler as a demon whose victory would herald the end of human civilization, bringing instead a "return to barbarism ... tribalism, and beastliness".[3]

Plays

The publication and performance of his play, Ahl al-Kahf (The People of the Cave, 1933) was a significant event in Egyptian drama. The story of 'the people of the cave' is to be found in the eighteenth surah of the Qur'an as well as in other sources. It concerns the tale of the seven sleepers of Ephesus who, in order to escape the Roman persecution of Christians, take refuge in a cave. They sleep for three hundred years, and wake up in a completely different era - without realizing it, of course. In its use of overarching themes - rebirth into a new world and a predilection for returning to the past - al-Hakim's play obviously touches upon some of the broad cultural topics that were of major concern to intellectuals at the time, and, because of the play's obvious seriousness of purpose, most critics have chosen to emphasise such features.

Within a year al-Hakim produced another major and highly revered work, Shahrazad (Scheherazade, 1934). While the title character is, of course, the famous narrator of the One Thousand and One Nights collection, the scenario for this play is set after all the tales have been told. Now cured of his vicious anger against the female sex by the story-telling virtuosity of the woman who is now his wife, King Shahriyar abandons his previous ways and embarks on a journey in quest of knowledge, only to discover himself caught in a dilemma whose focus is Shahrazad herself; through a linkage to the ancient goddess, Isis, Shahrazad emerges as the ultimate mystery, the source of life and knowledge. Even though the play is now considered one of his finest works, Taha Hussein, a prominent Arab writer and one of the leading intellectuals of the then Egypt criticized some of its aspects, mainly that it was not suitable for a theatrical performance. Later, the two writers wrote together a novel called The Enchanted Castle (Al-Qasr al-Mashur, 1936) in which both authors revisited some of the themes from al-Hakim's play. [4] When the National Theatre Troupe was formed in Egypt in 1935, the first production that it mounted was The People of the Cave. The performances were not a success; for one thing, audiences seemed unimpressed by a performance in which the action on stage was so limited in comparison with the more popular types of drama. It was such problems in the realm of both production and reception that seem to have led al-Hakim to use some of his play-prefaces in order to develop the notion of his plays as 'théâtre des idées', works for reading rather than performance. However, in spite of such critical controversies, he continued to write plays with philosophical themes culled from a variety of cultural sources: Pygmalion (1942), an interesting blend of the legends of Pygmalion and Narcissus.

Some of al-Hakim's frustrations with the performance aspect were diverted by an invitation in 1945 to write a series of short plays for publication in newspaper article form. These works were gathered together into two collections, Masrah al-Mugtama (Theatre of Society, 1950) and al-Masrah al-Munawwa (Theatre Miscellany, 1956). The most memorable of these plays is Ughniyyat al-Mawt (Death Song), a one-act play that with masterly economy depicts the fraught atmosphere in Upper Egypt as a family awaits the return of the eldest son, a student in Cairo, in order that he may carry out a murder in response to the expectations of a blood feud.

Al-Hakim's response to the social transformations brought about by the 1952 revolution, which he later criticized, was the play Al Aydi Al Na'imah (Soft Hands, 1954). The 'soft hands' of the title refer to those of a prince of the former royal family who finds himself without a meaningful role in the new society, a position in which he is joined by a young academic who has just finished writing a doctoral thesis on the uses of the Arabic preposition hatta. The play explores in an amusing, yet rather obviously didactic, fashion, the ways in which these two apparently useless individuals set about identifying roles for themselves in the new socialist context. While this play may be somewhat lacking in subtlety, it clearly illustrates in the context of al-Hakim's development as a playwright the way in which he had developed his technique in order to broach topics of contemporary interest, not least through a closer linkage between the pacing of dialogue and actions on stage. His play formed the basis of a popular Egyptian film by the same name, starring Ahmed Mazhar.

In 1960 al-Hakim was to provide further illustration of this development in technique with another play set in an earlier period of Egyptian history, Al Sultan Al-Ha'ir (The Perplexed Sultan ). The play explores in a most effective manner the issue of the legitimation of power. A Mamluk sultan at the height of his power is suddenly faced with the fact that he has never been manumitted and that he is thus ineligible to be ruler. By 1960 when this play was published, some of the initial euphoria and hope engendered by the Nasserist regime itself, given expression in Al Aydi Al Na'imah, had begun to fade. The Egyptian people found themselves confronting some unsavoury realities: the use of the secret police to squelch the public expression of opinion, for example, and the personality cult surrounding the figure of Gamal Abdel Nasser. In such a historical context al-Hakim's play can be seen as a somewhat courageous statement of the need for even the mightiest to adhere to the laws of the land and specifically a plea to the ruling military regime to eschew the use of violence and instead seek legitimacy through application of the law.

A two volume English translation of collected plays is in the UNESCO Collection of Representative Works.[5]

Style and themes

The theatrical art of al-Hakim consists of three types:

1- Biographical Theatre: The group of plays he wrote in his early life in which he expressed his personal experience and attitudes towards life were more than 400 plays among which were "al-Arees", (The Groom) and "Amama Shibbak al-Tazaker", (Before the Ticket Office). These plays were more artistic because they were based on Al Hakim's personal opinion in criticizing social life.

2- Intellectual Theatre: This dramatic style produced plays to be read not acted. Thus, he refused to call them plays and published them in separate books.

3- Objective Theatre: Its aim is to contribute to the Egyptian society by fixing some values of the society, exposing the realities of Egyptian life.

Al-Hakim was able to understand nature and depict it in a style which combines symbolism, reality and imagination. He mastered narration, dialogue and selecting settings. While al-Hakim's earlier plays were all composed in the literary language, he was to conduct a number of experiments with different levels of dramatic language. In the play, Al-Safqah (The Deal, 1956), for example - with its themes of land ownership and the exploitation of poor peasant farmers - he couched the dialogue in something he termed 'a third language', one that could be read as a text in the standard written language of literature, but that could also be performed on stage in a way which, while not exactly the idiom of Egyptian Arabic, was certainly comprehensible to a larger population than the literate elite of the city. There is perhaps an irony in the fact that another of al-Hakim's plays of the 1960s, Ya tali al-Shajarah (1962; The Tree Climber, 1966), was one of his most successful works from this point of view, precisely because its use of the literary language in the dialogue was a major contributor to the non-reality of the atmosphere in this Theatre of the Absurd style involving extensive passages of non-communication between husband and wife. Al-Hakim continued to write plays during the 1960s, among the most popular of which were Masir Sorsar (The Fate of a Cockroach, 1966) and Bank al-Qalaq (Anxiety Bank, 1967).

Influence and impact on Arabic literature

Tawfiq al-Hakim is one of the major pioneer figures in modern Arabic literature. In the particular realm of theatre, he fulfills an overarching role as the sole founder of an entire literary tradition, as Taha Hussein had earlier made clear. His struggles on behalf of Arabic drama as a literary genre, its techniques, and its language, are coterminous with the achievement of a central role in contemporary Egyptian political and social life.

Hakim's 1956 play Death Song was the basis of the libretto to Mohammed Fairouz's 2008 opera Sumeida's Song. [6]

Personal life

Hakim was viewed as something of a misogynist in his younger years, having written a few misogynistic articles and remaining a bachelor for an unusually long period of time; he was given the laqab (i.e. epithet) of عدو المرأة ('Aduww al Mar'a), meaning "Enemy of woman." However, he eventually married and had two children, a son and a daughter. His wife died in 1977; his son died in 1978 in a car accident. He died July 23, 1987.[7]

List of works

- A Bullet in the Heart, 1926 (Plays)

- Leaving Paradise, 1926 (Plays)

- The Diary of a Country Prosecutor, 1933 (Novel) (translation exists at least into Spanish, German and Swedish, and into English by Abba Eban as Maze of Justice (1947))

- The People of the Cave, 1933 (Play)

- The Return of the Spirit, 1933 (Novel)

- Shahrazad, 1934 (Play)

- Muhammad the Prophet, 1936 (Biography)

- A Man without a Soul, 1937 (Play)

- A Sparrow from the East, 1938 (Novel)

- Ash'ab, 1938 (Novel)

- The Devil's Era, 1938 (Philosophical Stories)

- My Donkey told me, 1938 (Philosophical Essays)

- Praxa/The problem of ruling, 1939 (Play)

- The Dancer of the Temple, 1939 (Short Stories)

- Pygmalion, 1942

- Solomon the Wise, 1943

- Boss Kudrez's Building, 1948

- King Oedipus, 1949

- Soft Hands, 1954

- Equilibrium, 1955

- Isis, 1955

- The Deal, 1956

- The Sultan's Dilemma, 1960

- The Tree Climber, 1966

- The Fate of a Cockroach, 1966

- Anxiety Bank, 1967

- The Return of Consciousness, 1974

External links

References

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Tawfiq Hakim |

- "The achievements of Tawfiq Al-Hakim". Cambridge University Press. 2000. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- Goldschmidt, Arthur (2000), "al-Hakim, Tawfiq", Biographical Dictionary of Modern Egypt, Lynne Rienner Publishers, p. 52, ISBN 1-55587-229-8,

Playwright, novelist, and essayist. Tawfiq was born in Ramleh, Alexandria, to an Egyptian landowning father and an aristocratic Turkish mother.

- Israel Gershoni (2008). "Demon and Infidel". In Francis Nicosia & Boğaç Ergene (ed.). Nazism, the Holocaust and the Middle East. Berghan Books. pp. 82–85.

- Beskova, Katarina (2016). "In the Enchanted Castle with Shahrazad: Taha Husayn and Tawfiq al-Hakim between Friendship and Rivalry". Arabic and Islamic Studies in Honour of Ján Pauliny. Comenius University in Bratislava: 33–47. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Plays, Prefaces and Postscripts. Vol. I: Theatre of the Mind". www.unesco.org.

- Rase, Sherri (April 8, 2011), Conversations—with Mohammed Fairouz Archived 2012-03-22 at the Wayback Machine, [Q]onStage, retrieved 2011-04-19

- Asharq Al-Awsat, This Day in History-July 23: The Death of Tawfiq al-Hakim, July 23, 1992