Modern Standard Arabic

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), or Modern Written Arabic (shortened to MWA),[2] is a term used mostly by Western linguists[3] to refer to the variety of standardized, literary Arabic that developed in the Arab world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is the language used in academia, print and mass media, law and legislation, though it is generally not spoken as a mother tongue, like Classical Latin or Soutenu French.[3] MSA is a pluricentric standard language taught throughout the Arab world in formal education. It differs significantly from many vernacular varieties of Arabic that are commonly spoken as mother tongues in the area; these are only partially mutually intelligible with both MSA and with each other depending on their proximity in the Arabic dialect continuum.

| Modern Standard Arabic | |

|---|---|

| العربية الفصحى, عربي فصيح al-ʻArabīyah al-Fuṣḥā, ʻArabī Faṣīḥ[note 1] | |

al-ʻArabīyah written in Arabic (Naskh script) | |

| Pronunciation | /al ʕaraˈbijja lˈfusˤħaː/, see variations[note 2] |

| Region | Primarily in the Arab League, in the Middle East and North Africa; and in the Horn of Africa; liturgical language of Islam |

Native speakers | None[1] (second language only)[note 3] |

Afro-Asiatic

| |

Early forms | |

| Arabic alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | International Organizations

|

| Regulated by | List

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | arb |

arb-mod | |

| Glottolog | stan1318 |

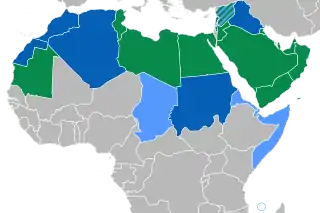

Distribution of Modern Standard Arabic as an official language in the Arab World. The only official language (green); one of the official languages (blue). | |

Western linguists consider MSA to be distinct from what they call Classical Arabic (CA; اللغة العربية الفصحى التراثية al-Lughah al-ʻArabīyah al-Fuṣḥā al-Turāthīyah)—the variety of standard Arabic in the Quran and early Islamic (7th to 9th centuries) literature. MSA differs most markedly in that it either synthesizes words from Arabic roots (such as سيارة car or باخرة steamship) or adapts words from European languages (such as ورشة workshop or إنترنت Internet) to describe industrial and post-industrial life.

Native speakers of Arabic generally do not distinguish between "Modern Standard Arabic" and "Classical Arabic" as separate languages; they refer to both as al-ʻArabīyah al-Fuṣḥā (العربية الفصحى) meaning "the eloquent Arabic".[4] They consider the two forms to be two registers of one language. When the distinction is made, they are referred to as فصحى العصر Fuṣḥā al-ʻAṣr (MSA) and فصحى التراث Fuṣḥā al-Turāth (CA) respectively.[4]

History

Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic, also known as Quranic Arabic (although the term is not entirely accurate), is the language used in the Quran as well as in numerous literary texts from Umayyad and Abbasid times (7th to 9th centuries). Many Muslims study Classical Arabic in order to read the Quran in its original language. It is important to note that written Classical Arabic underwent fundamental changes during the early Islamic era, adding dots to distinguish similarly written letters, and adding the tashkīl (diacritical markings that guide pronunciation) by Abu al-Aswad al-Du'ali, Al-Khalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi, and other scholars. It was the lingua franca across the Middle East, North Africa, and the Horn of Africa during classic times and in Andalusia before classic times.

Emergence of Modern Standard Arabic

Napoleon's campaign in Egypt and Syria (1798–1801) is generally considered to be the starting point of the modern period of the Arabic language, when the intensity of contacts between the Western world and Arabic culture increased.[5] Napoleon introduced the first Arabic printing press in Egypt in 1798; it briefly disappeared after the French departure in 1801, but Muhammad Ali Pasha, who also sent students to Italy, France and England to study military and applied sciences in 1809, reintroduced it a few years later in Boulaq, Cairo.[5] (Previously, Arabic-language presses had been introduced locally in Lebanon in 1610 , and in Aleppo, Syria in 1702[5]). The first Arabic printed newspaper was established in 1828: the bilingual Turkish-Arabic Al-Waqa'i' al-Misriyya had great influence in the formation of Modern Standard Arabic.[5] It was followed by Al-Ahram (1875) and al-Muqattam (1889).[5] The Western–Arabic contacts and technological developments in especially the newspaper industry indirectly caused the revival of Arabic literature, or Nahda, in the late 19th and early 20th century.[5] Another important development was the establishment of Arabic-only schools in reaction against the Turkification of Arabic-majority areas under Ottoman rule.[5]

Current situation

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is the literary standard across the Middle East, North Africa and Horn of Africa, and is one of the six official languages of the United Nations. Most printed material by the Arab League—including most books, newspapers, magazines, official documents, and reading primers for small children—is written in MSA. "Colloquial" Arabic refers to the many regional dialects derived from Classical Arabic spoken daily across the region and learned as a first language, and as second language if people speak other languages native to their particular country. They are not normally written, although a certain amount of literature (particularly plays and poetry, including songs) exists in many of them.

Literary Arabic (MSA) is the official language of all Arab League countries and is the only form of Arabic taught in schools at all stages. Additionally, some members of religious minorities recite prayers in it, as it is considered the literary language. Translated versions of the Bible which are used in Arabic-speaking countries are mostly written in MSA, aside from Classical Arabic. Muslims recite prayers in it; revised editions of numerous literary texts from Umayyad and Abbasid times are also written in MSA.

The sociolinguistic situation of Arabic in modern times provides a prime example of the linguistic phenomenon of diglossia – the use of two distinct varieties of the same language, usually in different social contexts.[6] This diglossic situation facilitates code-switching in which a speaker switches back and forth between the two dialects of the language, sometimes even within the same sentence. People speak MSA as a third language if they speak other languages native to a country as their first language and colloquial Arabic dialects as their second language. Modern Standard Arabic is also spoken by people of Arab descent outside the Arab world when people of Arab descent speaking different dialects communicate to each other. As there is a prestige or standard dialect of vernacular Arabic, speakers of standard colloquial dialects code-switch between these particular dialects and MSA.

Classical Arabic is considered normative; a few contemporary authors attempt (with varying degrees of success) to follow the syntactic and grammatical norms laid down by classical grammarians (such as Sibawayh) and to use the vocabulary defined in classical dictionaries (such as the Lisan al-Arab, Arabic: لِسَان الْعَرَب).

However, the exigencies of modernity have led to the adoption of numerous terms which would have been mysterious to a classical author, whether taken from other languages (e. g. فيلم film) or coined from existing lexical resources (e. g. هاتف hātif "caller" > "telephone"). Structural influence from foreign languages or from the vernaculars has also affected Modern Standard Arabic: for example, MSA texts sometimes use the format "A, B, C and D" when listing things, whereas Classical Arabic prefers "A and B and C and D", and subject-initial sentences may be more common in MSA than in Classical Arabic.[7] For these reasons, Modern Standard Arabic is generally treated separately in non-Arab sources.[8] Speakers of Modern Standard Arabic do not always observe the intricate rules of Classical Arabic grammar. Modern Standard Arabic principally differs from Classical Arabic in three areas: lexicon, stylistics, and certain innovations on the periphery that are not strictly regulated by the classical authorities. On the whole, Modern Standard Arabic is not homogeneous; there are authors who write in a style very close to the classical models and others who try to create new stylistic patterns.[9] Add to this regional differences in vocabulary depending upon the influence of the local Arabic varieties and the influences of foreign languages, such as French in Africa and Lebanon or English in Egypt, Jordan, and other countries.[10]

As MSA is a revised and simplified form of Classical Arabic, MSA in terms of lexicon omitted the obsolete words used in Classical Arabic. As diglossia is involved, various Arabic dialects freely borrow words from MSA. This situation is similar to Romance languages, wherein scores of words were borrowed directly from formal Latin (most literate Romance speakers were also literate in Latin); educated speakers of standard colloquial dialects speak in this kind of communication.

Reading out loud in MSA for various reasons is becoming increasingly simpler, using less strict rules compared to CA, notably the inflection is omitted, making it closer to spoken varieties of Arabic. It depends on the speaker's knowledge and attitude to the grammar of Classical Arabic, as well as the region and the intended audience.

Pronunciation of native words, loanwords, foreign names in MSA is loose, names can be pronounced or even spelled differently in different regions and by different speakers. Pronunciation also depends on the person's education, linguistic knowledge and abilities. There may be sounds used, which are missing in the Classical Arabic but may exist in colloquial varieties - consonants - /v/, /p/, /t͡ʃ/ (often realized as [t]+[ʃ]), these consonants may or may not be written with special letters; and vowels - [o], [e] (both short and long), there are no special letters in Arabic to distinguish between [e~i] and [o~u] pairs but the sounds o and e (short and long) exist in the colloquial varieties of Arabic and some foreign words in MSA. The differentiation of pronunciation of informal dialects is the influence from other languages previously spoken and some still presently spoken in the regions, such as Coptic in Egypt, French, Ottoman Turkish, Italian, Spanish, Berber, Punic or Phoenician in North Africa, Himyaritic, Modern South Arabian and Old South Arabian in Yemen and Aramaic in the Levant.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Denti-alveolar | Palato- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | ||||||||||

| Nasal | m م | n ن | |||||||||

| Stop | voiceless | (p)3 | t ت | tˤ ط | k ك | q ق | ʔ ء | ||||

| voiced | b ب | d د | dˤ ض | d͡ʒ1 ج | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f ف | θ ث | s س | sˤ ص | ʃ ش | x ~ χ خ | ħ ح | h ه | ||

| voiced | (v)3 | ð ذ | z ز | ðˤ ظ | ɣ ~ ʁ غ | ʕ ع | |||||

| Trill | r ر | ||||||||||

| Approximant | l ل | (ɫ)2 | j ي | w و | |||||||

- Notes:

1. The standard consonant varies regionally, most prominently [d͡ʒ] in the Arabian Peninsula, parts of the Levant, Iraq, and northern Algeria and Sudan, [ʒ] in most of Northwest Africa and the Levant, [g] in Egypt and southern Yemen.

2. the marginal phoneme /ɫ/ only occurs in the word الله /aɫ.ɫaːh/ ('The God') and words derived from it.[11]

3. /p, v/ are foreign consonants used by a number of speakers in loanwords, their usage is not standard, and they can be written with the modified letters پ /p/ and ڤ /v/ (in some parts of North Africa it is written as ڥ).

Vowels

Modern Standard Arabic, like Classical Arabic before it, has three pairs of long and short vowels: /a/, /i/, and /u/:

| Short | Long | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | Front | Back | |

| Close | i | u | iː | uː |

| Mid | (eː)* | (oː)* | ||

| Open | a | aː | ||

* Footnote: although not part of Standard Arabic phonology the vowels /eː/ and /oː/ are perceived as separate phonemes in most of modern Arabic dialects and they are occasionally used when speaking Modern Standard Arabic as part of foreign words or when speaking it with a colloquial tone.

- Across North Africa and West Asia, short /i/ may be realized as [ɪ ~ e ~ ɨ] before or adjacent to emphatic consonants and [q], [r], [ħ], [ʕ] depending on the accent.

- Short /u/ can also have different realizations, i.e. [ʊ ~ o ~ ʉ]. Sometimes with one value for each vowel in both short and long lengths or two different values for each short and long lengths.

- In Egypt, close vowels have different values; short initial or medial: [e], [o] ← instead of /i, u/.

- In some other particular dialects /i~ɪ/ and /u~ʊ/ completely become /e/ and /o/ respectively.

- Allophones of /a/ and /aː/ include [ɑ] and [ɑː] before or adjacent to emphatic consonants and [q], [r]; and [æ] and [æː] elsewhere.

- Allophones of /iː/ include [ɪː]~[ɨː] before or adjacent to emphatic consonants and [q], [r], [ħ], [ʕ].

- Allophones of /uː/ include [ʊː]~[ɤː]~[oː] before or adjacent to emphatic consonants and [q], [r], [ħ], [ʕ].

- Unstressed final long /aː, iː, uː/ are most often shortened or reduced: /aː/ → [æ ~ ɑ], /iː/ → /i/, /uː/ → [o~u].

Differences between Modern Standard Arabic and Classical Arabic

While there are differences between Modern Standard Arabic and Classical Arabic, Arabic speakers tend to find these differences unimportant, and generally refer to both by the same name: al-ʻArabīyah al-Fuṣḥā ('the eloquent Arabic').

Differences in syntax

MSA tends to use simplified sentence structures and drop more complicated ones commonly used in Classical Arabic. Some examples include reliance on verb sentences instead of noun phrases and semi-sentences, as well as avoiding phrasal adjectives and accommodating feminine forms of ranks and job titles.

Differences in terminology

Because MSA speech occurs in fields with novel concepts, including technical literature and scientific domains, the need for terms that did not exist in the time of CA has led to coining new terms. Arabic Language Academies had attempted to fulfill this role during the second half of the 20th century with neologisms with Arab roots, but MSA typically borrows terms from other languages to coin new terminology.[12]

Differences in pronunciation

MSA includes two sounds not present in CA, particularly /p/ and /v/, which occur in loanwords. In addition, MSA normally does not use diacritics (tashkīl) unless there is a need for disambiguation or instruction, unlike the CA found in Quran and Hadith scriptures, which are texts that demand strict adherence to exact wording.[12] MSA also has taken on some punctuation marking from other languages.

Regional variants

MSA is loosely uniform across the Middle East as it is based on the convention of Arabic speakers rather than being a regulated language which rules are followed (that is despite the number of academies regulating Arabic). It can be thought of as being in a continuum between CA (the regulated language described in grammar books) and the spoken vernaculars while leaning much more to CA in its written form than its spoken form.

Regional variations exist due to influence from the spoken vernaculars. TV hosts who read prepared MSA scripts, for example in Al Jazeera, are ordered to give up national or ethnic pronunciations by changing their pronunciation of certain phonemes (e.g. the realization of the Classical jīm ج as [ɡ] by Egyptians), though other traits may show the speaker's region, such as the stress and the exact value of vowels and the pronunciation of other consonants. People who speak MSA also mix vernacular and Classical in pronunciation, words, and grammatical forms. Classical/vernacular mixing in formal writing can also be found (e.g., in some Egyptian newspaper editorials); others are written in Modern Standard/vernacular mixing, including entertainment news.

Speakers

The Egyptian writer and journalist, Cherif Choubachy wrote in a critical book, that more than half of the Arabic speaking world are not Arabs and that more than 50% of Arabs in the Arabic speaking world use Literary Arabic.[13]

People who are literate in Modern Standard Arabic are primarily found in most countries of the Arab League. It is compulsory in schools of most of the Arab League to learn Modern Standard Arabic. People who are literate in the language are usually more so passively, as they mostly use the language in reading and writing, not in speaking.

The countries with the largest populations that mandate MSA be taught in all schools are, with rounded-up numbers (data from 2008—2014):

Grammar

Common phrases

| Translation | Phrase | IPA | Romanization (ALA-LC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic | العربية | /alʕaraˈbij.ja/ | al-ʻArabīyah |

| hello/welcome | مرحباً, أهلاً وسهلاً | /marħaban, ʔahlan wa sahlan/ | marḥaban, ahlan wa-sahlan |

| peace [be] with you (lit. upon you) | السلام عليكم | /assaˈlaːmu ʕaˈlajkum/ | as-salāmu ʻalaykum |

| how are you? | كيف حالك؟ | /ˈkajfa ˈħaːluk, -luki/ | kayfa ḥāluk, ḥāluki |

| see you | إلى اللقاء | /ʔila l.liqaːʔ/ | ila al-liqāʼ |

| goodbye | مع السلامة | /maʕa s.saˈlaːma/ | maʻa as-salāmah |

| please | من فضلك | /min ˈfadˤlik/ | min faḍlik |

| thanks | شكراً | /ˈʃukran/ | shukran |

| that (one) | ذلك | /ˈðaːlik/ | dhālik |

| How much/How many? | كم؟ | /kam/ | kam? |

| English | الإنجليزية/الإنكليزية/الإنقليزية | (varies) /alʔing(i)li(ː)ˈzij.ja/ | (may vary) al-inglīzīyah |

| What is your name? | ما اسمك؟ | /masmuk, -ki/ | masmuka / -ki? |

| I don't know | لا أعرف | /laː ˈʔaʕrif/ | lā aʻrif |

See also

- Arabic language

- Varieties of Arabic

- Arabic literature

- Arab League

- Geographic distribution of Arabic

- Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic

- Arabic English Lexicon

- Diglossia

- Arabic phonology

- Help:IPA/Arabic

- Pluricentric language

Notes

- Spelling for the final letter yāʼ differs in Egypt, Sudan and sometimes other regions as Yemen. It is always undotted ى, hence عربى فصيح.

- Pronunciation varies regionally. The following are examples:

- The Levant: [al ʕaraˈbɪjja lˈfʊsˤħa], colloquially: [(e)l-]

- Hejaz: [al ʕaraˈbijjalˈfusˤħa]

- East central Arabia: [æl ʢɑrɑˈbɪjjɐ lˈfʊsˤʜɐ], colloquially: [el-]

- Egypt: [æl ʕɑɾɑˈbejjɑ lˈfosˤħɑ], colloquially: [el-]

- Libya: [æl ʕɑrˤɑˈbijjæ lˈfusˤħæ], colloquially: [əl-]

- Tunisia: [æl ʕɑrˤɑˈbeːjæ lˈfʊsˤħæ], colloquially: [el-]

- Algeria, Morocco: [æl ʕɑrˤɑbijjæ lfusˤħæ], colloquially: [l-]

- Modern Standard Arabic is not commonly taught as a native language in the Arabic-speaking world, as speakers of various dialects of Arabic would first learn to speak their respective local dialect. Modern Standard Arabic is the most common standardized form of Arabic taught in primary education throughout the Arab world.

References

- Modern Standard Arabic at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Gully, Adrian; Carter, Mike; Badawi, Elsaid (29 July 2015). Modern Written Arabic: A Comprehensive Grammar (2 ed.). Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 978-0415667494.

- Kamusella, Tomasz (2017). "The Arabic Language: A Latin of Modernity?" (PDF). Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics. 11 (2): 117–145. doi:10.1515/jnmlp-2017-0006. S2CID 158624482.

- Alaa Elgibali and El-Said M. Badawi. Understanding Arabic: Essays in Contemporary Arabic Linguistics in Honor of El-Said M. Badawi, 1996. Page 105.

- van Mol, Mark (2003). Variation in Modern Standard Arabic in Radio News Broadcasts: A Synchronic Descriptive Investigation Into the Use of Complementary Particles. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 25–27. ISBN 9789042911581. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- Farghaly, A., Shaalan, K. Arabic Natural Language Processing: Challenges and Solutions, ACM Transactions on Asian Language Information Processing (TALIP), the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), 8(4)1-22, December 2009.

- Alan S. Kaye (1991). "The Hamzat al-Waṣl in Contemporary Modern Standard Arabic". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 111 (3): 572–574. doi:10.2307/604273. JSTOR 604273.

- http://www.londonarabictuition.com/lessons.php?type=2 London Arabic Tuition

- https://asianabsolute.co.uk/arabic-language-dialects/ Arabic Language Dialects

- Wolfdietrich Fischer. 1997. "Classical Arabic," The Semitic Languages. London: Routledge. Pg 189.

- Watson (2002:16)

- Arabic, AL. "White Paper". msarabic.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- Choubachy, Cherif (2004). "4". لتحيا اللغة العربية: يسقط سيبويه (in Arabic). الهيئة المصرية العامة للكتب. pp. 125–126. ISBN 977-01-9069-1.

- "Official Egyptian Population clock". capmas.gov.eg.

- The World Factbook. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 2014-04-28.

- "World Population Prospects, Table A.1" (PDF). 2008 revision. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2009: 17. Retrieved 22 September 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - http://www.cbs.gov.sd 2008 Sudanese census

Further reading

- van Mol, Mark (2003). Variation in Modern Standard Arabic in Radio News Broadcasts: A Synchronic Descriptive Investigation Into the Use of Complementary Particles. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042911581.

- Holes, Clive (2004). Modern Arabic: Structures, Functions, and Varieties. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 1-58901-022-1

External links

| Look up Classical Arabic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up Modern Standard Arabic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up Fus-ha in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |