Tetris Holding, LLC v. Xio Interactive, Inc.

Tetris Holding, LLC v. Xio Interactive, Inc. is a legal case related to copyright of video games establishing that a video game's look and feel can be protected under copyright law.

| Tetris Holding, LLC v. Xio Interactive, Inc. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | United States District Court for the District of New Jersey |

| Full case name | Tetris Holding, LLC and The Tetris Company v. Xio Interactive, Inc. |

| Decided | May 30, 2012 |

| Citation(s) | 863 F.Supp.2d 394 (D.N.J. 2012) |

| Transcript(s) | Opinion |

| Court membership | |

| Judge sitting | Freda L. Wolfson |

Facts

In 2008, Apple launched the iPhone App Store, which prompted a large number of developers to launch games for the new platform. One such developer was Desiree Golden who, under the developer name Xio Interactive, released an iOS app called Mino which was based on the gameplay of Tetris. Mino featured the same approach of using falling tetromino blocks to form complete lines on a playfield and score points. Golden had carefully worded the marketing of the game to avoid all references to Tetris, outside of a disclaimer which read: "Mino and Xio Interactive are not affiliated with Tetris (tm) or the Tetris Company (tm)". This was a common disclaimer used by clone makers to avoid litigation in light of the current idea-expression distinction of copyright law.[1]

Tetris, which was first introduced in 1984 by its creator Alexey Pajitnov, had become one of the most successful video games of all time and was now owned by Tetris Holding, LLC, and with the rights exclusively licensed through The Tetris Company. While Mino was not the first Tetris clone, it was one of the most visible ones at the time of the release, becoming available to upwards of six million iPhone users. In August 2009, Tetris Holdings sent DMCA notices to Xio via Apple requesting that Apple take Mino down from the App Store. While Apple initially complied with Tetris's request, Xio filed a counter-notice, which prompted Apple to re-instate Mino and inform Tetris Holdings that they could not have the software removed unless they filed a lawsuit against Xio. Tetris subsequently filed suit against Xio Interactive in December 2009 in the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey.[1]

Legal background

The earliest video game case law was an extension of other copyright cases in media and technology, offering copyright protection to original characters, but not to gameplay systems that are essential to produce a game.[2] Prior to Xio, video games were recognized to fall within the idea-expression distinction of the Copyright Act of 1976; one could not claim copyright on the ideas of a video game, such as gameplay concepts, only on the manner in which they were expressed, such as the specific art assets or music.[3] The Copyright Office advised that "Copyright does not protect the idea for a game, its name or title, or the method or methods for playing it. Nor does copyright protect any idea, system, method, device, or trademark material involved in developing, merchandising, or playing a game. Once a game has been made public, nothing in copyright law prevents others from developing another game based on similar principles."[4] Adjunct to this are two basic principles: the merger doctrine which states that sometimes the ideas and expression of those ideas are so closely tied together that it is impossible to separate the two, and thus the expression becomes ineligible for copyright, and scènes à faire (French for "scenes to be made") which are considers parts of expressive speech that are essential to the scene or genre of expression, such as how the presence of a baseball is essential to the presentation of a baseball game and thus ineligible for copyright. These doctrines of copyright law permitted cloning of video games that closely matched gameplay concepts but with new assets or other audio and visual differences.[1]

District court

The case was assigned to Judge Freda L. Wolfson. Judge Wolfson reviewed two of the five claims brought by Tetris, a first claim for copyright infringement and a second claim for trademark infringement via the game's trade dress. In defending the copyright claim, Golden admitted to having copied Mino directly from the official Tetris app that was developed under license by Electronic Arts, and that prior to publishing the game, had sought a license to Tetris from Tetris Holdings but was denied one. Subsequently Golden researched copyright law and continued to develop Mino based on case law around video games, stressing that video games were only covered by through their expression, and because Mino used completely new audio and video assets, there was no copyright infringement.[5]

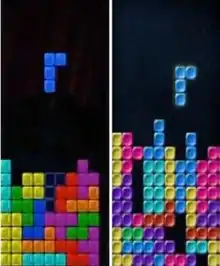

Judge Wolfson ruled early that, as previously established, the gameplay of Tetris was not copyrightable. While the New Jersey district court was within the Third Circuit and which had prior case law from Whelan v. Jaslow (797 F.2d 1222 (1987)) that used a purpose-based test to abstract software to determine if copyright was infringed, Wolfson opted to explore prior case law from other circuits through the Abstraction-Filtration-Comparison test (AFC) for substantial similarity that had been first defined in Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp. (45 F.2d 119 (1930)) and applied to computer software in Computer Associates International, Inc. v. Altai, Inc. (982 F.2d 693 (1992)). Two video game cases, Atari, Inc. v. North American Philips Consumer Electronics Corp. (related to the copyright of K.C. Munchkin! to Pac-Man) and Midway Manufacturing Co. v. Bandai-America, Inc. (related to handheld clones of Midway's Galaxian) were found to have been ruled in the same manner as the AFC test, according to Wolfson, and thus was applicable to the Mino case. To apply the AFC test to Mino, Judge Wolfson compared the games "as they would appear to a layman [by] concentrating upon the gross features rather than an examination of minutiae", essentially comparing the games' respective look and feel; Wolfson further wrote "[i]f one has to squint to find distinctions only at a granular level, then the works are likely to be substantially similar".[6]

Wolfson concluded quickly that Mino failed the AFC test with respect to Tetris since the two games looked similar side-by-side. Further, Wolfson rejected the merger doctrine claim that Golden had proposed, since the details of the art style used in the Tetris blocks had "are not part of the ideas, rules, or functions of the game nor are they essential or inseparable from the ideas, rules, or functions of the game." Wolfson further dismissed Golden's scènes à faire arguments, ruling that Tetris was a unique game and thus had no established stock or common imagery that would be ineligible for protection.[6] In weighing these arguments, Wolfson noted that Mino copied Tetris much more closely than a game like Dr. Mario, a game utilized the rules of Tetris in a non-infringing way to create unique expression.[7]

Wolfson also agreed with Tetris Holdings that Mino's trade dress violated their trade dress, since the look and feel was too similar to Tetris but was not essential to the operation of the game.[6]

Wolfson subsequently granted summary judgment in Tetris's favor on both counts in May 2012, which required Golden to withdraw the game from the App Store.[6][5]

Impact

Legal scholars have included this decision in a wave of cases that have pushed the boundaries of video game copyright protection, along with Electronic Arts Inc. v. Zynga Inc.[8] As Golden did not appeal the case to the Third Circuit, the decision is only binding precedent on the District of New Jersey. However other courts have cited the ruling as relevant case law in evaluating other video game cloning cases and have relied upon it to establish a new approach to evaluating copyrights surrounding the look and feel of video games.[1][9] Scholars have argued that this case represents the game medium coming of age, evolving from rudimentary gameplay into sufficiently expressive systems that are worthy of copyright protection.[2] This coincides with the legal system having more experience and understanding of video games, where the judge who decided the case was 18 when Pong was released.[10] The ruling shows the courts using a "high level of understanding of video game mechanics for the first time".[7]

For example, shortly after the decision in Xio, another cloning case was heard in the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington, brought by Spry Fox against developer Lolapps over their game Yeti Town which Spry Fox claimed was a copyright-infringing clone of Triple Town. At the initial hearings, the judge followed similar logic used in the Xio case to order a preliminary injunction in favor of Spry Fox, as Yeti Town had the same look-and-feel as Triple Town when simply viewed side by side. The case was subsequently settled out of court, with Spyr Fox gaining ownership of the Yeti Town property by the end of 2012.[9]

Since these cases in 2012, legal scholars have found that courts have been more scrutinizing of look-and-feel in cases involving video game clones. While idea-expression distinction, merger doctrine and scènes à faire remain driving principles for games based on more realistic visuals, abstract games may be more unique and lack pre-established form, allowing their look-and-feel to be more rigorously evaluated through abstraction as part of a copyright lawsuit.[11] Susan Corbett argues that "the Tetris decision supports the view that United States courts are becoming more accepting of the possibility of offering broader copyright protection for videogames".[12] Tomasz Grzegorczyk notes that this case shows courts are willing to recognize that the "graphic user interface of the game is subject to protection under copyright in the same manner as audiovisual works".[13] Noting that the copyright infringing game copied exact shapes and colors, Steven Conway and Jennifer deWinter argue that the decision would not impact other alleged game clones that are less similar.[14] Josh Davenport and Ross Dannenberg suggest that while a "standard game device" may be too generic to warrant copyright protection, that a specific selection or arrangement of those devices would quality as unique expression, and thus copyrightable.[2] John Kuehl calls this case a potential killing blow to knock off video games that are near copies of the original.[7]

Despite warnings that the case might lead to an explosion of intellectual property disputes and copyright trolls, there has only been an incremental increase, with the courts applying this legal standard carefully to new cases.[7] Nicholas Lampros also noted that the facts of this case were highly specific, leading to "a narrow, fact-heavy legal standard, the outcome of which is difficult to predict outside of court". He added that this would put more onus on digital distribution platforms to manage potentially infringing products.[1] Tom Phillips has noted that the high cost and uncertainty of fact-specific litigation has led developers to hold each other accountable in the media, as an alternative to legal action.[15]

References

- Lampros, Nicholas M. (2013). "Leveling Pains: Clone Gaming And The Changing Dynamics Of An Industry" (PDF). Berkeley Technology Law Journal. 28: 743–774. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- Dannenberg, Ross; Davenport, Josh (2018-12-01). "Top 10 video game cases (US): how video game litigation in the US has evolved since the advent of Pong". Interactive Entertainment Law Review. 1 (2): 89–102. doi:10.4337/ielr.2018.02.02. ISSN 2515-3870.

- Parkin, Simon (2011-12-23). "Clone Wars: is plagiarism killing creativity in the games industry?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2015-10-16. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- "U.S. Copyright Office – Games". United States Copyright Office. Archived from the original on 2014-02-09. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- "Judge Declares iOS Tetris Clone 'Infringing'". Wired. June 21, 2012. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- Casillas, Brian (2014). "Attack Of The Clones: Copyright Protection For Video Game Developers". Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review. 33: 137–170. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- Kuehl, John (2016). "Video Games and Intellectual Property:Similarities, Differences, and a New Approach toProtection". Cybaris:Vol. 7: Issue 2, Article 4.

- Castree, III, Sam (September 8, 2013). "A Problem Old as Pong: Video Game Cloning and the Proper Bounds of Video Game Copyrights".

- McArthur, Stephen (2013-02-27). "Clone Wars: The Six Most Important Cases Every Game Developer Should Know". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 2013-03-02. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- Quagliariello, John (2019). "Applying Copyright Law to Videogames: Litigation Strategies for Lawyers" (PDF). Harvard Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law. 10: 263.

- Dean, Drew S. (215). "Hitting reset: Devising a new video game copyright regime". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 164: 1239–1280. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- Corbett, Susan (2016). "Videogames and their clones – How copyright law might address the problem - PDF Free Download". computer law & security review. Retrieved 2021-01-31.

- Grzegorczyk, Tomasz (April 2017). "Qualification of Computer Games in Copyright Law".

- Conway, Steven; deWinter, Jennifer (2015-10-14). Video Game Policy: Production, Distribution, and Consumption. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-60722-9.

- Phillips, Tom (2015-04-03). ""Don't clone my indie game, bro": Informal cultures of videogame regulation in the independent sector". Cultural Trends. 24 (2): 143–153. doi:10.1080/09548963.2015.1031480. ISSN 0954-8963.