The Wiz (film)

The Wiz is a 1978 American musical adventure fantasy film produced by Universal Pictures and Motown Productions and released by Universal Pictures on October 24, 1978. A reimagining of L. Frank Baum's classic 1900 children's novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz featuring an all-black cast, the film was loosely adapted from the 1974 Broadway musical of the same name. It follows the adventures of Dorothy, a shy, twenty-four-year-old Harlem schoolteacher who finds herself magically transported to the urban fantasy Land of Oz, which resembles a dream version of New York City. Befriended by a Scarecrow, a Tin Man, and a Cowardly Lion, she travels through the city to seek an audience with the mysterious Wiz, who they say is the only one powerful enough to send her home.

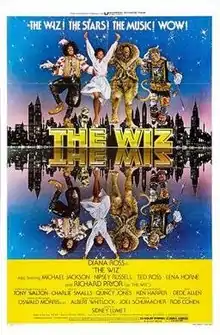

| The Wiz | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sidney Lumet |

| Produced by | Rob Cohen |

| Screenplay by | Joel Schumacher |

| Based on | |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Charlie Smalls |

| Cinematography | Oswald Morris |

| Edited by | Dede Allen |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 133 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $24 million[2] |

| Box office | $21 million[3] |

Produced by Rob Cohen and directed by Sidney Lumet, the film stars Diana Ross, Michael Jackson, Nipsey Russell, Ted Ross, Mabel King, Theresa Merritt, Thelma Carpenter, Lena Horne and Richard Pryor. Its story was reworked from William F. Brown's Broadway libretto by Joel Schumacher, and Quincy Jones supervised the adaptation of Charlie Smalls and Luther Vandross' songs for it. A handful of new songs, written by Jones and the songwriting team of Nickolas Ashford & Valerie Simpson, were added for it.

Upon its original theatrical release, the film was a critical and commercial failure, and marked the end of the resurgence of African-American films that began with the blaxploitation movement of the early 1970s.[4][5][6] Despite its initial failure, it became a cult classic among black audiences, Jackson's fanbase, and Oz enthusiasts.[7][8] Certain aspects influenced The Wiz Live!, a live television adaptation of the musical, aired on NBC in 2015.[9]

Plot

A crowded Thanksgiving dinner brings a host of family together in a small Harlem apartment, where a shy, twenty-four-year-old elementary schoolteacher named Dorothy Gale lives with her Aunt Em and Uncle Henry ("The Feeling We Once Had"). Extremely introverted, she is teased by Aunt Em for never having been south of 125th Street, as she has delayed moving out to start her own, independent life as an adult (“Can I Go On?” - written for the film).

While Dorothy cleans up after the meal, her dog, Toto, runs out the open kitchen door into a snowstorm. She succeeds in retrieving him but finds herself trapped in the storm. A magical whirlwind made of snow – the work of Glinda, the Good Witch of the South – materializes and transports them to the city realm of Oz. Released by the snowstorm, as Dorothy descends from the atmosphere she smashes through an electric "Oz" sky sign, which falls upon and kills Evermean, the Wicked Witch of the East who rules Munchkinland. As a result, she frees the Munchkins who populate the playground into which she lands; they had been transformed into graffiti by Evermean for painting the playground walls.

Dorothy soon meets the Munchkins' main benefactress, Miss One, the Good Witch of the North, a magical "numbers runner" who gives Evermean's pretty charmed silver slippers to her by teleporting them onto Dorothy's feet. However, Dorothy declares she does not want the shoes and desperately just wants to get home to Aunt Em. Miss One urges her to follow the yellow brick road to the Emerald City and seek the help of the powerful "Wiz" who she believes holds the power to send Dorothy back to Harlem (“He’s the Wiz”). After telling her to never take the silver shoes off, Miss One and the Munchkins disappear and Dorothy is left to search for the road on her own (“Soon As I Get Home”).

The next morning, Dorothy happens upon a Scarecrow made of garbage, and is friends with him after saving him from being teased by a group of humanoid crows (“You Can’t Win”). They discover the yellow brick road and happily begin to follow it together ("Ease on Down the Road"). The Scarecrow hopes the Wiz might be able to give him the one thing he feels that he lacks – a brain. Along the way to the Emerald City, Dorothy, Toto and the Scarecrow meet the Tin Man in an abandoned early 20th-century amusement park (“If I Could Feel” / “Slide Some Oil to Me”) and the Cowardly Lion named Fleetwood Coupe DeVille, a vain dandy who hid inside one of the stone lions in front of the New York Public Library after being banished from the jungle (“Mean-Ol’ Lion”). The Tin Man and Lion join them on their quest to find the Wiz, hoping to gain a heart and courage, respectively. En route to the Emerald City, the adventurers must pass through a subway controlled by a crazy peddler (a homeless man) who controls evil puppets. Other deadly monsters all awaken and try to kill the group (such as trash cans that try to crush the Scarecrow by his arms, a fuse box electrocuting the Tin Man, and the pillars that try to crush Dorothy), but the Lion bravely rescues his friends by fighting off the monsters. They narrowly escape the subway, only to encounter flamboyant prostitutes known as the "Poppy" Girls (a reference to the poppy field from the original story). They attempt to put Dorothy, Toto and the Lion into an eternal sleep with magic poppy perfume (“Be a Lion”).

Finally reaching the Emerald City, the four friends gains passage into the city because of Dorothy's ownership of the silver slippers. They marvel at the spectacle of the city and its sophisticated, fashion-forward dancers. They are granted an audience with the Wiz, who lives at the very top of the Towers and appears to them as a giant fire-breathing metallic head. He will only grant their wishes if they kill the sister of the Wicked Witch of the East, Evillene, the Wicked Witch of the West, who runs a sweatshop in the underground sewers of Oz. Before they can reach her domain, Evillene learns of their quest to kill her and sends out the Flying Monkeys (a motorcycle gang) to keep them at bay (“No Bad News”).

After a long chase, the Flying Monkeys succeed in capturing their targets and bring them back to Evillene. Vengeful for Dorothy having killed her sister, she dismembers the Scarecrow, flattens the Tin Man, and hangs the Lion up by his tail in hopes of making Dorothy give her the silver shoes. When she threatens to throw Toto into a fiery cauldron, Dorothy nearly gives in until the Scarecrow hints to her to activate a fire sprinkler switch, which she does. The sprinklers put out the fire but also melt Evillene, who is made of ice. She is flushed down into her throne, the lid of which slams shut like a toilet. With Evillene dead, her spells lose their power: the Winkies are freed from their permanent costumes (revealing attractive humans underneath) and their sweatshop tools disappear. They break into song-and-dance ("Everybody Rejoice") and praise Dorothy as their emancipator. The Flying Monkeys give her and her friends a triumphant ride back to the Emerald City.

Upon arriving, the quartet takes a back door into the Wiz's quarters and discovers that he is a phony because the Wiz is actually Herman Smith, a failed politician from Atlantic City, New Jersey, who was transported to Oz when a balloon he was flying to promote his campaign to become the city dogcatcher was lost in a storm. The Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Lion are distraught that they will never receive their respective brain, heart, and courage, but Dorothy makes them realize that they already have had these things all along (“Believe”). Just as it seems as if she will never be able to get home, Glinda, the Good Witch of the South, appears and implores her to find her way home by searching within and using the magic of the silver slippers (“Believe”—reprise). After thanking Glinda and saying goodbye to her friends, she reminisces about home (“Home”). She clicks her heels together three times. She looks up and discovers she is back near home with Toto in her arms and walks into the apartment repeating the phrase "There's no place like home!"

Cast

- Diana Ross as Dorothy Gale

- Michael Jackson as Scarecrow

- Nipsey Russell as Tin Man

- Ted Ross as Cowardly Lion/Fleetwood Coupe DeVille

- Richard Pryor as Herman Smith/The Wiz

- Lena Horne as Glinda the Good Witch of the South

- Mabel King as Evillene the Wicked Witch of the West

- Thelma Carpenter as Miss One the Good Witch of the North

- Theresa Merritt as Shelby Gale/Aunt Em

- Stanley Greene as Uncle Henry

Music

All songs written by Charlie Smalls, unless otherwise noted.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Overture Part I" | 2:36 | ||

| 2. | "Overture Part II" | 1:57 | ||

| 3. | "The Feeling We Once Had" | Aunt Em and Chorus | 3:26 | |

| 4. | "Can I Go On?" | Quincy Jones, Nickolas Ashford and Valerie Simpson | Dorothy | 1:56 |

| 5. | "Tornado / Glinda's Theme" | 1:10 | ||

| 6. | "He's the Wizard" | Miss One and Chorus | 4:09 | |

| 7. | "Soon As I Get Home / Home" | Dorothy | 4:04 | |

| 8. | "You Can't Win, You Can't Break Even" | Scarecrow and The Four Crows | 3:14 | |

| 9. | "Ease on Down the Road #1" | Dorothy and Scarecrow | 3:55 | |

| 10. | "What Would I Do If I Could Feel?" | Tin Man | 2:18 | |

| 11. | "Slide Some Oil to Me" | Tin Man | 2:51 | |

| 12. | "Ease on Down the Road #2" | Dorothy, Scarecrow and Tin man | 1:31 | |

| 13. | "I'm a Mean Ole Lion" | Cowardly Lion | 2:24 | |

| 14. | "Ease on Down the Road #3" | Dorothy, Scarecrow, Tin Man and Cowardly Lion | 1:26 | |

| 15. | "Poppy Girls Theme" | Anthony Jackson | 3:27 | |

| 16. | "Be a Lion" | Dorothy, Scarecrow, Tin Man and Cowardly Lion | 4:04 | |

| 17. | "End of the Yellow Brick Road" | 1:01 | ||

| 18. | "Emerald City Sequence" | (music: Jones, lyrics: Smalls) | Chorus | 6:44 |

| 19. | "Is This What Feeling Gets? (Dorothy's Theme)" | (music: Jones, lyrics: Ashford & Simpson) | Dorothy - (vocal version not used in film) | 3:21 |

| 20. | "Don't Nobody Bring Me No Bad News" | Evillene and the Winkies | 3:03 | |

| 21. | "Everybody Rejoice / A Brand New Day" | Luther Vandross | Dorothy, Scarecrow, Tin Man, Cowardly Lion and Chorus | 7:49 |

| 22. | "Believe in Yourself (Dorothy)" | Dorothy | 2:55 | |

| 23. | "The Good Witch Glinda" | 1:09 | ||

| 24. | "Believe in Yourself (Reprise)" | Glinda the Good Witch | 2:15 | |

| 25. | "Home (Finale)" | Dorothy | 4:03 |

Production

Pre-production and development

The Wiz was the eighth feature film produced by Motown Productions, the film/TV division of Berry Gordy's Motown Records label. Gordy originally wanted the teenaged future R&B singer Stephanie Mills, who had originated the role on Broadway, to be cast as Dorothy. When Motown star Diana Ross asked Gordy if she could be cast as Dorothy, he declined, saying that Ross—then 33 years old—was too old for the role.[10] Ross went around Gordy and convinced executive producer Rob Cohen at Universal Pictures to arrange a deal where he would produce the film if Ross was cast as Dorothy. Gordy and Cohen agreed to the deal. Pauline Kael, a film critic, described Ross's efforts to get the film into production as "perhaps the strongest example of sheer will in film history."[10]

After film director John Badham learned that Ross was going to play the part of Dorothy, he decided not to direct the film, and Cohen replaced him with Sidney Lumet.[10] Of his decision not to direct The Wiz, John Badham recalled telling Cohen that he thought Ross was "a wonderful singer. She's a terrific actress and a great dancer, but she's not this character. She's not the little six-year-old girl Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz."[11] Though 20th Century Fox had financially backed the stage musical, they ended up exercising their first refusal rights to the film production, which gave Universal an opening to finance the film.[12] Initially, Universal was so excited about the film's prospects that they did not set a budget for production.[12]

Joel Schumacher's script for The Wiz was influenced by Werner Erhard's teachings and his Erhard Seminars Training ("est") movement, as both Schumacher and Ross were "very enamored of Werner Erhard".[13] "Before I knew it," said Rob Cohen, "the movie was becoming an est-ian fable full of est buzzwords about knowing who you are and sharing and all that. I hated the script a lot. But it was hard to argue with [Ross] because she was recognizing in this script all of this stuff that she had worked out in est seminars."[13] Schumacher spoke positively of the results of the est training, stating that he was "eternally grateful for learning that I was responsible for my life."[13] However, he also complained that "everybody stayed exactly the way they were and went around spouting all this bull shit."[13] Of est and Erhard references in the film itself, The Grove Book of Hollywood notes that the speech delivered by Glinda the Good Witch at the end of the film was "a litany of est-like platitudes", and the book also makes est comparisons to the song "Believe in Yourself".[13] Although Schumacher had seen the Broadway play before writing the script, none of the Broadway play's writing was incorporated into the film's.[14]

During production, Lumet felt that the finished film would be "an absolutely unique experience that nobody has ever witnessed before."[12] When asked about any possible influence from MGM's popular 1939 film adaptation of The Wizard of Oz, Lumet stated that "there was nothing to be gained from [the 1939 film] other than to make certain we didn't use anything from it. They made a brilliant movie, and even though our concept is different – they're Kansas, we're New York; they're white, we're black, and the score and the books are totally different – we wanted to make sure that we never overlapped in any area."[12]

Michael Jackson, a former Motown star and close friend of Diana Ross, was cast as the Scarecrow. By the start of development on The Wiz in 1977, he and his brothers The Jacksons had left Motown for Epic Records after the release of their tenth album Moving Violation, though Jackson had yet to make a solo album since his fourth album Forever, Michael. Rob Cohen, head of Motown Productions, thought Jackson would be perfect for the role of the Scarecrow, and approached Berry Gordy with the idea, who agreed, though director Sidney Lumet was harder to convince.[15] Lumet wanted Jimmie Walker, star of CBS-TV’s Good Times, telling Cohen “Michael Jackson’s a Vegas act. The Jackson 5’s a Vegas act.” Quincy Jones was also skeptical of Jackson, but after Cohen arranged a meeting, flying 19-year-old Jackson to New York, Lumet and Jones saw the qualities that Cohen saw. Jackson's father, Joseph Jackson, was wary of the project and saw it as a threat to the Jacksons group cohesion. Cohen moved Michael and his sister La Toya Jackson into a Manhattan apartment, allowing him to be on his own for the first time. During the production, he became a frequent visitor to New York's famous Studio 54. Jackson was dedicated to the Scarecrow role, and watched videotapes of gazelles, cheetahs and panthers in order to learn graceful movements for his part.[16] The long hours of uncomfortable prosthetic makeup by Stan Winston did not bother him. During the production of the film, Jackson asked Quincy Jones who he would recommend as a producer on a yet unrecorded solo album project. Jones, impressed by Jackson's professionalism, talent and work ethic on the film, offered to be producer of what became Off The Wall (1979), then later on the hugely successful albums Thriller (1982) and Bad (1987).

Ted Ross and Mabel King were brought in to reprise their respective roles from the stage musical, while Nipsey Russell was cast as the Tin Man. Lena Horne, mother-in-law to Lumet during the time of production, was cast as Glinda the Good Witch, and comedian Richard Pryor portrayed The Wiz.[10][17] The film's choreographer was Louis Johnson.[18] One of the cast members Michael Jackson was friends with Judy Garland's and Vincente Minnelli's daughter Liza Minnelli.

Principal photography

The Wiz was filmed at Astoria Studios in Queens, New York. The decaying New York State Pavilion from the 1964 New York World's Fair was used as the set for Munchkinland, Astroland at Coney Island was used for the Tinman scene with The Cyclone as a backdrop, while the World Trade Center served as the Emerald City.[19] The scenes filmed at the Emerald City were elaborate, utilizing 650 dancers, 385 crew members and 1,200 costumes.[19][20] Costume designer Tony Walton enlisted the help of high fashion designers in New York City for the Emerald City sequence, and obtained exotic costumes and fabric from designers such as Oscar de la Renta and Norma Kamali.[17] Albert Whitlock created the film's visual special effects,[12] while Stan Winston served as the head makeup artist.[17]

Quincy Jones was the musical supervisor and music producer for the film.[16] He later wrote that he initially did not want to work on the film, but did it as a favor to Lumet.[16] The film production marked Jones' first time working with Jackson, and Jones later produced three hit albums for Jackson: Off the Wall (1979), Thriller (1982) and Bad (1987).[21] Jones recalled working with Jackson as one of his favorite experiences from The Wiz, and spoke of Jackson's dedication to his role, comparing his acting style to Sammy Davis, Jr.[16] Jones had a brief cameo during the "Gold" segment of the Emerald City sequence, playing what looks like a fifty-foot grand piano.

Release and reception

Box office

The Wiz proved to be a commercial failure, as the $24 million production only earned $13.6 million at the box office.[2][3][10] Though prerelease television broadcast rights had been sold to CBS for over $10 million, in the end, the film produced a net loss of $10.4 million for Motown and Universal.[3][10] At the time, it was the most expensive film musical ever made.[22] The film's failure steered Hollywood studios away from producing the all-black film projects that had become popular during the blaxploitation era of the early to mid-1970s for several years.[4][5][6]

Home media

The film was released on VHS home video in 1989 by MCA/Universal Home Video (with a reissue in 1992) and was first broadcast on television on CBS on May 5, 1984 (edited to 100 minutes), to capitalize on Michael Jackson's massive popularity at the time.[23] It continues to be broadcast periodically on Black-focused networks such as BET, TVOne, BET Her, and was the inaugural broadcast on the Bounce TV digital broadcast network.[24] The Wiz is often broadcast on Thanksgiving Day (attributed to the opening scene of Dorothy's family gathered for a Thanksgiving dinner).[10][25]

The film was released on DVD in 1999;[26] a remastered version entitled The Wiz: 30th Anniversary Edition was released in 2008.[26][27][28] Extras on both DVD releases include a 1978 featurette about the film's production and the original theatrical trailer.[26] A Blu-ray version was released in 2010.[29]

Critical reception

Critics panned The Wiz upon its October 1978 release.[2][30] Many reviewers directed their criticism at Diana Ross, who they believed was too old to play Dorothy.[6][31][32][33] Most agreed that what had worked so successfully on stage simply did not translate well to the screen. Hischak's Through the Screen Door: What Happened to the Broadway Musical When It Went to Hollywood criticized "Joel Schumacher's cockamamy screenplay", and called "Believe in Yourself" the score's weakest song.[31] He described Diana Ross's portrayal of Dorothy as: "cold, neurotic and oddly unattractive"; and noted that the film was "a critical and box office bust".[31] In his work History of the American Cinema, Harpole characterized the film as "one of the decade's biggest failures", and, "the year's biggest musical flop".[3] The Grove Book of Hollywood noted that "the picture finished off Diana Ross's screen career", as the film was Ross's final theatrical feature.[13][20][34] In his 2004 book Blockbuster, Tom Shone referred to The Wiz as "expensive crud".[35] In the book Mr. and Mrs. Hollywood, the author criticized the script, noting, "The Wiz was too scary for children, and too silly for adults."[2] Ray Bolger, who played the Scarecrow in the 1939 The Wizard of Oz film, did not think highly of The Wiz, stating "The Wiz is overblown and will never have the universal appeal that the classic MGM musical has obtained."[36]

Jackson's performance as the Scarecrow was one of the only positively reviewed elements of the film, with critics noting that Jackson possessed "genuine acting talent" and "provided the only genuinely memorable moments."[19][37] Of the results of the film, Jackson stated: "I don't think it could have been any better, I really don't."[38] In 1980, Jackson stated that his time working on The Wiz was "my greatest experience so far . . . I'll never forget that."[37] The film received a positive critique for its elaborate set design, and the book American Jewish Filmmakers noted that it "features some of the most imaginative adaptations of New York locales since the glory days of the Astaire-Rogers films."[39] In a 2004 review of the film, Christopher Null wrote positively of Ted Ross and Richard Pryor's performances.[40] However, Null's overall review of the film was critical, and he wrote that other than the song "Ease on Down the Road", "the rest is an acid trip of bad dancing, garish sets, and a Joel Schumacher-scripted mess that runs 135 agonizing minutes."[40] A 2005 piece by Hank Stuever in The Washington Post described the film as "a rather appreciable delight, even when it's a mess", and felt that the singing – especially Diana Ross's – was "a marvel".[41]

The New York Times analyzed the film within a discussion of the genre of blaxploitation: "As the audience for blaxploitation dwindled, it seemed as if Car Wash and The Wiz might be the last gasp of what had been a steadily expanding black presence in mainstream filmmaking."[42] The St. Petersburg Times noted, "Of course, it only took one flop like The Wiz (1978) to give Hollywood an excuse to retreat to safer (i.e., whiter) creative ground until John Singleton and Spike Lee came along. Yet, without blaxploitation there might not have been another generation of black filmmakers, no Denzel Washington or Angela Bassett, or they might have taken longer to emerge."[43] The Boston Globe commented, "the term 'black film' should be struck from the critical vocabulary. To appreciate just how outmoded, deceptive and limiting it is, consider the following, all of which have been described as black films, . . ." and characterized The Wiz in a list that also featured 1970s films Shaft (1971), Blacula (1972), and Super Fly (1972).[44]

Despite its lack of critical or commercial success in its original release, The Wiz became a cult classic,[7] especially because it features Michael Jackson in his first starring theatrical film role. Jackson later starred in films such as Disney's Captain EO in 1986, the anthology film Moonwalker in 1988 and the posthumous documentary This Is It in 2009.[8]

As of August 2019, The Wiz holds a 42% rating on Rotten Tomatoes from 33 reviews, with the consensus; "This workmanlike movie musical lacks the electricity of the stage version (and its cinematic inspiration), but it's bolstered by strong performances by Diana Ross and Michael Jackson."[45]

Awards and honors

| Nomination | Recipients |

|---|---|

| Best Art Direction | Art Direction: Tony Walton and Philip Rosenberg; Set Decoration: Edward Stewart and Robert Drumheller |

| Best Costume Design | Tony Walton |

| Best Song Score or Adaptation Score | Quincy Jones |

| Best Cinematography | Oswald Morris |

| Winner | Recipients |

|---|---|

| Outstanding Actor in a Motion Picture | Michael Jackson |

See also

References

- "The Wiz (U)". British Board of Film Classification. December 7, 1978. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- Sharp, Kathleen (2003). Mr. and Mrs. Hollywood: Edie and Lew Wasserman and Their Entertainment Empire. Carroll & Graf Publishers. pp. 357–358. ISBN 0-7867-1220-1.

- Harpole, Charles (2003). History of the American Cinema. Simon & Schuster. pp. 64, 65, 219, 220, 290. ISBN 0-684-80463-8.

- Moon, Spencer; George Hill (1997). Reel Black Talk: A Sourcebook of 50 American Filmmakers. Greenwood Press. xii. ISBN 0-313-29830-0.

- Benshoff, Harry M.; Sean Griffin (2004). America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies. Blackwell Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 0-631-22583-8.

- George, Nelson (1985). Where Did Our Love Go? The Rise and Fall of the Motown Sound. St. Martin's Press. p. 193.

- Han, Angie (March 31, 2015). "NBC Teaming With Cirque du Soleil for 'The Wiz' Live Musical". Slashfilm. Slashfilm. p. N01. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- Howard, Adam (April 11, 2011). "How Lumet's 'The Wiz' became a black cult classic". The Grio. The Grio. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- Ne-Yo (actor) (November 25, 2015). "The Wiz LIVE!" Cast! (live television interview). Retrieved December 29, 2015.

This is a kind of blend of the Broadway musical and the movie, so it's like both of them combined.

- Adrahtas, Thomas (2006). A Lifetime to Get Here: Diana Ross: The American Dreamgirl. AuthorHouse. pp. 163–167. ISBN 1-4259-7140-7.

- Emery, Robert J. (2002). The Directors: Take One. Allworth Communications, Inc. p. 333. ISBN 1-58115-219-1.

- Lumet, Sidney; Joanna E. Rapf (2006). Sidney Lumet: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 78, 80. ISBN 1-57806-724-3.

- Silvester, Christopher; Steven Bach (2002). The Grove Book of Hollywood. Grove Press. pp. 555–560. ISBN 0-8021-3878-0.

- Vanairsdale, S.T. (2011). "Joel Schumacher Tells Movieline About the Time He Wrote The Wiz". Movieline.com. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- http://time.com/4135018/the-wiz-michael-jackson/

- Jones, Quincy (2002). Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones. Broadway Books. pp. 229, 259. ISBN 0-7679-0510-5.

- Pecktal, Lynn; Tony Walton (1999). Costume Design: Techniques of Modern Masters. Back Stage Books. pp. 215–218. ISBN 0-8230-8812-X.

- Kourlas, Gia (April 10, 2020). "Louis Johnson, 90, Genre-Crossing Dancer and Choreographer, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Campbell, Lisa D. (1993). Michael Jackson: The King of Pop. Branden Books. p. 41. ISBN 0-8283-1957-X.

- Kempton, Arthur (2005). Boogaloo: The Quintessence Of American Popular Music. University of Michigan Press. p. 316. ISBN 0-472-03087-6.

- Bronson, Fred (2003). Billboard's Hottest Hot 100 Hits. Watson-Guptill. p. 107. ISBN 0-8230-7738-1.

- Skow, John (October 30, 1978). "Nowhere Over the Rainbow". TIME. Time Warner. Retrieved November 6, 2007.

- Staff. "TVTango Listings for May 5, 1984". TVTango.com. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- The Deadline Team (August 24, 2011). "Bounce TV To Launch With 'The Wiz'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- Nowlan, Robert A.; Gwendolyn Wright Nowlan (1989). Cinema Sequels and Remakes, 1903–1987. McFarland & Co Inc Pub. p. 834. ISBN 0-89950-314-4.

- Jackson, Alex (2008) "DVD review of The Wiz: 30th Anniversary Edition Archived March 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine". Film Freak Central. Retrieved March 9, 2008.

- Conti, Garrett (February 12, 2008). "New DVD releases include 'Gone Baby Gone'". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- Caine, Barry (February 8, 2008). "All you need is 'Across the Universe' on DVD". Contra Costa Times. San Jose Mercury News.

- "The Wiz Blu-Ray [Review]". November 30, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- Posner, Gerald (2002). Motown: Music, Money, Sex, and Power. New York: Random House. pp. s. 293–295.

- Hischak, Thomas S. (2004). Through the Screen Door: What Happened to the Broadway Musical When It Went to Hollywood. Scarecrow Press. pp. 140–142. ISBN 0-8108-5018-4.

- Halstead, Craig; Chris Cadman (2003). Michael Jackson the Solo Years. Authors on Line Ltd. pp. 25, 26. ISBN 0-7552-0091-8.

- Studwell, William E.; David F. Lonergan (1999). The Classic Rock and Roll Reader. Haworth Press. p. 137: "Ease on Down the Road". ISBN 0-7890-0151-9.

- Laufenberg, Norbert B. (2005). Entertainment Celebrities. Trafford Publishing. p. 562. ISBN 1-4120-5335-8.

- Shone, Tom (2004). Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer. Simon & Schuster. p. 34. ISBN 0-7432-3568-1.

- Fantle, David; Tom Johnson (2004). Reel to Real. Badger Books Inc. p. 58. ISBN 1-932542-04-3.

- Jackson, Michael; Catherine Dineen (1993). Michael Jackson: In His Own Words. Omnibus Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-7119-3216-6.

- Crouse, Richard (2000). Big Bang Baby: The Rock and Roll Trivia Book. Dundurn Press Ltd. pp. 158–159. ISBN 0-88882-219-7.

- Desser, David; Lester D. Friedman (2004). American Jewish Filmmakers. University of Illinois Press. p. 198. ISBN 0-252-07153-0.

- Null, Christopher (2004). "The Wiz Movie Review, DVD Release". Filmcritic.com. Christopher Null. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2007.

- Stuever, Hank (January 30, 2005). "Michael Jackson on Film: No Fizz After 'The Wiz'". The Washington Post. The Washington Post Company. p. N01. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- Harvey, Doug (December 31, 2000). "December 24–30 – Who's the Man? Shaft, John Shaft". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. p. 2.

- Persall, Steve (June 16, 2000). "The Return of Shaft: Bullets babes bad muthas and blaxploitation". St. Petersburg Times. p. 22W.

- Blowen, Michael (January 11, 1987). "Abolish term 'black films'". The Boston Globe. Globe Newspaper Company. p. B1.

- https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/wiz

- Staff (2007). "Database search for The Wiz". Oscars.org. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2007.

- Langman, Larry (2000). Destination Hollywood: The Influence of Europeans on American Filmmaking. McFarland & Company. pp. 155, 156. ISBN 0-7864-0681-X.

- "1979 Image Award Winners". Awardsandwinners. Retrieved May 21, 2017.

External links

- The Wiz at IMDb

- The Wiz at the TCM Movie Database

- The Wiz at AllMovie

- The Wiz at Box Office Mojo

- The Wiz at Rotten Tomatoes