The Woman on Pier 13

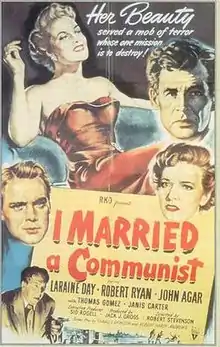

The Woman on Pier 13 is a 1949 American film noir drama directed by Robert Stevenson and starring Laraine Day, Robert Ryan, and John Agar.[2] It previewed in Los Angeles and San Francisco in 1949 under the title I Married a Communist but, owing to poor polling among preview audiences, this was dropped prior to its 1950 release.[1][3]

| The Woman on Pier 13 | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Stevenson |

| Produced by | Jack J. Gross |

| Screenplay by | Robert Hardy Andrews Charles Grayson |

| Story by | George W. George George F. Slavin |

| Starring | Laraine Day Robert Ryan John Agar |

| Music by | Leigh Harline |

| Cinematography | Nicholas Musuraca |

| Edited by | Roland Gross |

| Distributed by | RKO Pictures |

Release date | |

Running time | 73 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Plot

Brad Collins (Ryan), a San Francisco shipping executive (real name Frank Johnson) who recently married Nan Lowry Collins (Laraine Day) after a brief courtship, was once involved with a communist group in New York, while a stevedore during the Depression. Shortly after returning home following their honeymoon, the couple meet Christine Norman (Janis Carter), an old flame of Collins. Nan immediately dislikes her.

Collins becomes the target of a Communist cell and its leader, Vanning (Thomas Gomez), who orders an alleged FBI informer drowned after a brief interrogation. After threatening to reveal Collins' responsibility for a murder as well as his communist past, Vanning orders the executive to sabotage the shipping industry in the San Francisco Bay by resisting union demands in a labor dispute. He claims it is impossible to leave the Communist Party. Meanwhile Norman, bitter over Collins's earlier rejection, is ordered to become closer to his brother-in-law Don Lowry (Agar) by indoctrinating him with their Communist world view. Norman, though, genuinely falls in love with Lowry, with Vanning claiming that she is not meant to be so emotional.

A friend of Collins and former boyfriend of Nan, union leader Jim Travers (Richard Rober) cannot understand why Collins has become unreasonable to deal with. Travers is concerned about the possibility of the small number of communists in the union being able to take it over, and suspects Norman of being a communist, or at least a fellow traveler. He discusses this with Lowry, who is a new colleague. Lowry denies Norman's politics, apparently still free of communist ideology or at least an awareness of where his, by now, future wife's friends are coming from politically. She confesses when confronted, but after Lowry rejects her she shows him a photograph of herself with Collins/Johnson and reveals his communist past. Vanning interrupts them. Angry with Christine for breaking orders, who was supposed to be in Seattle for another two days on her day job as a photographer, Vanning tries to lean on Lowry because he is now able to expose the influence the party has regained over Collins.

Lowry travels to the Collins' residence to inform them of what he has learned, but is run over by a car driven by the communist hit man J.T. Arnold (Paul E. Burns) who had observed the earlier killing with Collins. Nan, previously informed by Norman that her brother is in danger, tries to convince her husband that Lowry's killing was not an accident. He pretends to be unconvinced. Confronting Christine, Nan is told of her husband's past, and Christine (falsely, though he was with Arnold) informs her that Bailey (William Talman) was probably responsible for Lowry's death. Preparing a suicide note, Christine is interrupted by Vanning, who thinks this is a good solution, but wishes to keep politics out of it, and destroys her confession of communist involvement. It is unclear if she does commit suicide, or whether she is thrown out of the high window.

Intent on revenge, Nan befriends Bailey at the fairground where he has legitimate employment, and goes off with him. The hit man is saved when she is identified, and Nan is kidnapped and taken to the hidden local communist headquarters in Arnold's warehouse. Collins tracks his wife down to this location, and by threatening Arnold with a gun, is able to gain admittance. In a shootout, Bailey and Vanning are killed, and Collins fatally injured. In his last moments Nan says she still loves him.

Cast

- Laraine Day as Nan Lowry Collins

- Robert Ryan as Brad Collins, aka Frank Johnson

- John Agar as Don Lowry

- Thomas Gomez as Vanning

- Janis Carter as Christine Norman

- Richard Rober as Jim Travers

- William Talman as Bailey, younger henchman

- Iris Adrian as the club waitress (uncredited)

Production

The original story forming the basis of the film by Slavin and George was first optioned then rejected by Eagle-Lion. It was announced in early September 1948 as RKO's first production following Howard Hughes takeover of the studio.[4]

Hughes reputedly offered the script to directors as a test for presumed communist leanings. Thirteen directors, according to Joseph Losey, turned down the film including himself.[5] John Cromwell said it was the worst film script he had ever read,[6] while Nicholas Ray departed shortly before production began. Production began in April 1949 under Robert Stevenson and lasted a month.[7] Newsreel footage of J. Edgar Hoover was requested, but denied because the FBI was aware of rumors Hughes was using the script as a ruse. The agency feared "persons of communist sympathies" would seek to undermine the project's intentions.[8] Robert Ryan, a liberal, was the only available contracted RKO actor and only agreed to be cast out of fear for his career. After the film had been completed, and ahead of planned retakes, Hughes insisted Ryan needed to be taught how to work with a gun, with screen tests of Ryan's progress being delivered to him personally.[9]

After the disappointing previews, Hughes still insisted the title I Married a Communist was the most marketable aspect of the picture, though his staff insisted otherwise. After a search, Hughes finally selected The Woman on Pier 13 in January 1950.[7]

Reception

Original release and box-office

When the film was released, the staff at Variety magazine wrote a tepid review, "As a straight action fare, I Married a Communist generates enough tension to satisfy the average customer. Despite its heavy sounding title, pic hews strictly to tried and true meller formula ... Pic is so wary of introducing any political gab that at one point when Commie trade union tactics are touched upon, the soundtrack is dropped."[10] The film was a commercial failure at the box-office,[11] and recorded a loss of $650,000.[12]

Later commentary

The British critic Tom Milne in the Time Out Film Guide wrote: "The sterling cast can make no headway against cartoon characters, a fatuous script that defies belief, and an enveloping sense of hysteria. Nick Musuraca's noir-ish camerawork, mercifully, is stunning."[13] In Dennis Schwartz's review, he questioned the film's veracity: "The story was filled with misinformation: it distorted the communist influence in the country and how big business and unions act. It attempted to make a propaganda film that reaffirms the American way of life and familial love, but at the expense of reality."[14]

Identifying The Woman on Pier 13 as an "amalgam of propaganda and noir", Jeff Smith considered it paradoxical "to use film to build political consensus" by borrowing "devices and storytelling strategies from the bleakest and most pessimistic films Hollywood ever made".[15]

References

- "The Woman on Pier 13: Detail View". American Film Institute. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- I Married a Communist at the TCM Movie Database.

- "The Woman on Pier 13: Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- "Hughes Schedules First Film at RKO". The New York Times. September 2, 1948. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- Ceplair, Larry; Englund, Steven (1983). The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960. Berkeley, Los Angeles & London: University of California Press. p. 389. ISBN 9780520048867.

- Canham, Kingsley (1976). The Hollywood Professionals, Volume 5: King Vidor, John Cromwell, Mervyn LeRoy. London: The Tantivy Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-498-01689-7.

- Jarlett, Franklin (1990). Robert Ryan: A Biography and Critical Filmography. Jefferson, N.C. & London: McFarland. p. 42–43. ISBN 9780786404766.

- Sbardellati, John (2012). J. Edgar Hoover Goes to the Movies: The FBI and the Origins of Hollywood's Cold War. Ithaca, NY & London: Cornell University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0801464683.

- Jones, J.R. (2015). "The Lives of Robert Ryan". Middetown, CT: Weslayan University Press. p. 97. ISBN 9780819573735.

- Variety. Staff, film review, 1951. Accessed: July 17, 2013.

- Smith, Jeff (2014). Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. Berkeley, Los Angeles & london: University of California Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780520280687.

- Jewell, Richard (2016). Slow Fade to Black: The Decline of RKO Radio Pictures. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780520289673.

- "I Married a Communist (1949) Movie Review". Time Out New York (timeout.com).; Time Out Film Guide 2009, 2008, p. 502.

- Schwartz, Dennis. Ozus' World Movie Reviews, film review, May 26, 2000. Accessed: July 17, 2013.

- Smith, Jeff Film Criticism, p. 58

External links

- The Woman on Pier 13 at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Woman on Pier 13 at IMDb

- The Woman on Pier 13 at AllMovie

- The Woman on Pier 13 at the TCM Movie Database

- The Woman on Pier 13 informational site and DVD review at DVD Beaver (includes images)