Third generation of video game consoles

In the history of computer and video games, the third generation (sometimes referred to as the 8-bit era) began on July 15, 1983, with the Japanese release of two systems: the Nintendo Family Computer (commonly abbreviated to Famicom) and the Sega SG-1000.[1][2] When the Famicom was released outside of Japan it was remodelled and marketed as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). This generation marked the end of the video game crash of 1983, and a shift in the dominance of home video game manufacturers from the United States to Japan.[3] Handheld consoles were not a major part of this generation, although the Game & Watch line from Nintendo had started in 1980 and the Milton Bradley Microvision came out in 1979 though both are considered second generation hardware.

| Part of a series on the |

| History of video games |

|---|

Improvements in technology gave consoles of this generation improved graphical and sound capabilities. The number of simultaneous colors on screen and the palette size both increased which, coupled with larger resolutions and more sprites on screen, meant that developers could create scenes with more detail. Five channel audio became common giving consoles the ability to produce a greater variation and range of sound. A notable innovation of this generation was the inclusion of cartridges with on-board memory and batteries to allow users to save their progress in a game, with Nintendo's The Legend of Zelda introducing the technology to the market. This innovation allowed for much more expansive gaming worlds and in-depth story telling, since users could now save their progress rather than having to start each gaming session at the beginning. By the next generation, the capability to save games became ubiquitous—at first saving on the game cartridge itself and, later, when the industry changed to read-only optical disks, on memory cards, hard disk drives, and eventually cloud storage.

The best-selling console of this generation was the NES/Famicom from Nintendo, followed by the Sega Master System (the improved successor to the SG-1000), and the Atari 7800. Although the previous generation of consoles had also used 8-bit processors, it was at the end of the third generation that home consoles were first labeled and marketed by their "bits". This also came into fashion as fourth generation 16-bit systems like the Sega Genesis were marketed in order to differentiate between the generations. In Japan and North America, this generation was primarily dominated by the Famicom/NES, while the Master System dominated the Brazilian market, with the combined markets of Europe being more balanced in overall sales between the two main systems. The end of the third generation was marked by the emergence of 16-bit systems of the fourth generation and with the discontinuation of the Famicom on September 25, 2003. However in some cases, the Third Generation still lives on as Dedicated console units still use hardware from the Famicom specs, especially in forms such as the VT02/VT03 & OneBus hardware which offers better graphical capabilities.

Overview

The generation began when Japanese companies, Sega and Nintendo, decided to enter the console gaming market. Sega released two consoles, SG-1000 and Mark III, and its competitor Nintendo released a Famicom home console. The companies were expected to have all of them only for the Japanese market.[4] However, the Famicom became very popular in Japan, and Nintendo decided to enter the worldwide market. With this in mind, the company approached the Atari company, which had the majority of the video game market in the rest of the world, with a proposal for Atari to license the Famicom and distribute it.[5] An agreement was concluded, which was to be signed at the Consumer Electronics Show in July 1983.[6]

At the same CES, however, Coleco exhibited its Coleco Adam home computer, which featured a Nintendo-designed game called Donkey Kong. At that time, Atari had exclusive rights to distribute Nintendo games on home computers, and Coleco had exclusive rights to distribute the game on consoles.[7] However, since Atari understood that Adam was a home computer, they postponed signing the agreement with Nintendo and asked the company to resolve the issue with rights.[8] The problem was resolved, but during this time, the video game crash of 1983 had occurred and Atari began to lose influence in the market. With this, Nintendo had no competitor left and the company decided to enter the market on its own.[9]

The company first introduced the Famicom in January 1985 at the Winter CES as the Nintendo Advanced Video System, short for NAVS. The gamepads were wireless and worked with it using an infrared port, and the bundle would also include a light gun. It was planned that the NAVS would be available in the spring of 1985.[10] However, this did not happen and the console was shown again at the summer CES in June of that year, in an updated version called the Nintendo Entertainment System.[11] The system was released in October 1985 as an experiment within New York City bounds with Super Mario Bros. game bundled. The experiment was successful and showed that people still wanted to play games despite the 1983 crisis. After that the system was released in all North America in February 1986 at a price of 159 USD.[12]

The Nintendo Family Computer (commonly abbreviated the Famicom) became popular in Japan during this era, crowding out the other consoles in this generation. The Famicom's Western counterpart, the Nintendo Entertainment System, dominated the gaming market in North America, thanks in part to its restrictive licensing agreements with developers. This marked a shift in the dominance of home video games from the United States to Japan, to the point that Computer Gaming World described the "Nintendo craze" as a "non-event" for American video game designers as "virtually all the work to date has been done in Japan."[3] The company had an estimated 65% of 1987 hardware sales in the console market; Atari Corporation had 24%, Sega had 8%, and other companies had 3%.[13]

The popularity of the Japanese consoles grew so quickly that in 1988 Epyx stated that, in contrast to a video game-hardware industry in 1984 that the company had described as "dead", the market for Nintendo cartridges was larger than for all home-computer software.[14] Nintendo sold seven million NES systems in 1988, almost as many as the number of Commodore 64s sold in its first five years.[15] Compute! reported that Nintendo's popularity caused most computer-game companies to have poor sales during Christmas that year, resulting in serious financial problems for some,[16] and after more than a decade making computer games, in 1989 Epyx converted completely to console cartridges.[17] By 1990 30% of American households owned the NES, compared to 23% for all personal computers,[18] and peer pressure to have a console was so great that even the children of computer-game developers demanded them despite parents' refusal and the presence of state-of-the-art computers and software at home. As Computer Gaming World reported in 1992, "The kids who don't have access to videogames are as culturally isolated as the kids in our own generation whose parents refused to buy a TV".[19]

Sega was Nintendo's main competitor for console sales during the era.[13] Sega's SG-1000, which preceded Sega's more commercially successful Master System, initially had little to distinguish itself from earlier consoles such as the ColecoVision and contemporary computers such as the MSX, although it was able to achieve advanced visual effects, including parallax scrolling in Orguss and sprite-scaling in Zoom 909.[1] In 1985, Sega's Master System incorporated hardware scrolling, alongside an increased color palette, greater memory, pseudo-3D effects, and stereoscopic 3-D, gaining a clear hardware advantage over the NES. However, the NES continued to dominate the North American and Japanese markets, while the Master System had more success in the European and South American markets.[20]

This era contributed many influential aspects to the history of the development of video games. The third generation saw the release of many of the first console role-playing video games (RPGs). Editing and censorship of video games was often used in localizing Japanese games to North America.[21] It was during this time that many successful video game franchises began, which went onto to becoming mainstays of the video game industry. Some examples are Super Mario Bros., Final Fantasy, The Legend of Zelda, Dragon Quest, Metroid, Mega Man, Metal Gear, Castlevania, Phantasy Star, Megami Tensei, Ninja Gaiden, and Bomberman.

The third generation also saw the beginning of the children's educational console market. Although consoles such as the VideoSmarts and ComputerSmarts systems were stripped down to very primitive input systems designed for children, their use of ROM cartridges established this as the standard for later such consoles. Due to their reduced capacities, these systems typically were not labeled by their "bits" and were not marketed in competition with traditional video game consoles.

In North America the Atari 7800 and Master System were discontinued in 1992, while the NES continued to be produced for several more years. In Europe, the Master System was discontinued in the late 1990s. However it has continued to sell in Brazil through to the present day. In Japan, Nintendo continued to repair Famicom systems until October 31, 2007.[22][23]

Home Systems

SG-1000

On July 15, 1983 the SG-1000 was released in Japan, the first console to be created by Sega.[24] It was released alongside the Famicom making them the first two consoles of the third generation. While it didn't sell as well as other consoles of the generation, it was considered important to the development of Sega as a console manufacturer.[25]

Famicom/Nintendo Entertainment System

The Famicom, released on July 15, 1983, in Japan and in the North American region in September 1986 as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES),[26] was an 8-bit cartridge based console developed and marketed by Nintendo. It became the most popular console of the generation, selling over 60 million units. It was the first home system to feature a controller with a directional pad designed by Gunpei Yokoi, which became an industry standard. While the NES was discontinued in North America on August 14, 1995, it wasn't until September 25, 2003, that the Famicom was discontinued in Japan.

Sega Master System

The Sega Mark III was released on October 20, 1985 for the Japanese market and was the third iteration of the SG-1000.[27] The name was changed to the Master System and the design altered for release outside of Japan. It was designed to be more powerful than the NES in an attempt to give it an edge over the competition but despite good sales, it couldn't match the success of the NES making it the second best selling console of the generation. This was the case in all regions apart from Brazil where it continued to sell for years after the end of the generation.

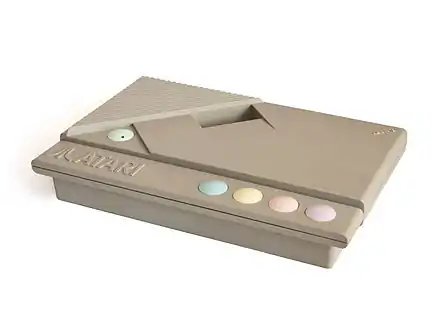

Atari 7800

The Atari 7800 was released in May 1986[28] and was the successor to the Atari 5200.[29] it was the first console to be backwards compatible without additional hardware. It was originally due for launch on May 21, 1984[30] but due to the sale of the company the launch didn't happen until two years later and coupled with a small library of games the console didn't sell well.[31]

Comparison

| Name | SG-1000 | Famicom/Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) | Sega Mark III/Master System | Atari 7800 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Sega | Nintendo | Sega | Atari | |

| Console |  |

|

|

| |

| Launch prices | JP¥15,000 (equivalent to ¥18,600 in 2019)[32] | JP¥14,800 (equivalent to ¥18,400 in 2019)[33] US$180(equivalent to US$430 in 2019)[34][35] CA$240 (equivalent to CA$510 in 2018) |

JP¥15,000 (equivalent to ¥17,800 in 2019)[27] US$199.99 (equivalent to $470 in 2019) UK£99.95 (equivalent to £280 in 2019)[36] |

US$140 (equivalent to $330 in 2019) | |

| Release date |

| ||||

| Media |

|

|

Cartridge | ||

| Top-selling games | N/A | Super Mario Bros. (pack-in), 40.24 million (as of 1999)[38] Super Mario Bros. 3, 18 million (as of May 21, 2003)[39] |

Hang-On and Safari Hunt (pack-in) Alex Kidd in Miracle World (pack-in) Sonic the Hedgehog (pack-in) |

Pole Position II (pack-in)[40] | |

| Backward compatibility | None | None | Sega SG-1000 (Japanese systems only) | Atari 2600 | |

| Accessories (retail) |

|

|

|

||

| CPU Clock speed |

NEC 780C (Z80-derived) (3.58 MHz (3.55 MHz PAL)[42] |

Ricoh 2A03 (6502-derived) (1.79 MHz (1.66 MHz PAL))[43]:149 |

Zilog Z80A 4 MHz |

Custom 6502C 1.19 MHz or 1.79 MHz | |

| GPU | Texas Instruments TMS9918 | Ricoh PPU (Picture Processing Unit) | Yamaha YM2602 VDP (Video Display Processor) | ||

| Sound chip(s) | Texas Instruments SN76489 |

Famicom Disk System: |

Japan only: |

Optional cartridge chip: | |

| Memory |

|

4.277344 KB (4380 bytes) RAM Upgrades: |

24.03125 KB (24,608 bytes) RAM |

4 KB RAM

| |

| Video | Resolution | 256×192[51] | 256×240[52] | 256×192, 256×224, 256×240 | 160×200 or 320×200 |

| Palette | 21 colors[42] | 54 colors)[43]:149 | 64 colors | 256 colors (16 hues, 16 luma) | |

| Colors on Screen | 16 simultaneous (1 color per sprite) | 25 simultaneous (4 colors per sprite) | 32 simultaneous (16 colors per sprite) | 25 simultaneous (1, 4 or 12 colors per sprite) | |

| Sprites |

|

| |||

| Background | Tilemap playfield, 8×8 tiles | Tilemap playfield, 8×8 tiles | Tilemap playfield, 8×8 tiles, tile flipping[50] | ||

| Scrolling | Smooth hardware scrolling, vertical/horizontal directions | Smooth hardware scrolling, vertical/horizontal/diagonal directions,[56] IRQ interrupt, line scrolling, split‑screen scrolling[55] MMC chips: IRQ interrupt, diagonal scrolling, line scrolling, split‑screen scrolling |

Coarse scrolling, vertical/horizontal directions | ||

| Audio | Mono audio with:[57]

|

Mono audio with:[58]

Japan only upgrades:

|

Mono audio with:

Japan only:

|

Mono audio with:[54]:121

Optional cartridge chip:

| |

Other consoles

Videopac+ G7400 (1983)

Videopac+ G7400 (1983) My Vision (1983)

My Vision (1983) PV-1000 (1983)

PV-1000 (1983) Super Cassette Vision (1984)

Super Cassette Vision (1984) BBC Bridge Companion (1985)

BBC Bridge Companion (1985) LJN Video Art

LJN Video Art

Released in 1985 Zemmix

Zemmix

Released in 1985 Halcyon (console)

Halcyon (console)

Unreleased (Planned for 1985)

Family Computer Disk System (1986)

Family Computer Disk System (1986) Atari XEGS (1987)

Atari XEGS (1987) Action Max (1987)

Action Max (1987)

VTech Socrates (1988)

VTech Socrates (1988) Amstrad GX4000 (1990)

Amstrad GX4000 (1990) Commodore 64 Games System (1990)

Commodore 64 Games System (1990)

Sales comparison

The NES/Famicom sold by far the most units of any third generation console in North America and Asia. In North America in 1989, between Nintendo and Sega, there was a 94% to 6% split between the two in market share between the NES and the Master System, in Nintendo's favor.[59] By 1992 in North America, Nintendo had a market-share of 80%, followed by Atari's 12% and Sega's 8%.[60] This was due to its strong lineup of first-party titles (such as Super Mario Bros., Metroid, Duck Hunt, and The Legend of Zelda), and Nintendo's strict licensing rules that required NES titles to be exclusive to the console for two years after release, putting a damper on third party support for other consoles.[61] Atari, on the other hand, fared a bit better than the Master System in North America, but still finished a distant second place. In Europe, competition was tougher for the NES with sales more evenly split, with the Master System possibly selling more despite the hegemony that it had in the North American and Japanese markets.[20][62]

| Console | Units sold worldwide | Japan | Americas | Elsewhere |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nintendo Entertainment System | 61.91 million (December 2009)[63][64] | 19.35 million (December 2009)[63] | 34 million (December 2009)[63] | 8.56 million (December 2009)[63] |

| Sega Master System | 17.8 million (2016) | 1 million (1986)[65] | United States: 2 million (1992)[66] Brazil: 8 million (2016)[67] | Western Europe: 6.8 million (1993)[68] |

Software

Milestone titles

- Alex Kidd in Miracle World (SMS) by Sega featured Sega's original mascot, Alex Kidd.[69]

- Castlevania (NES) by Konami, is loosely based on Bram Stoker's Dracula, featuring Count Dracula as main antagonist of series. This game initiated the Castlevania series.

- Dragon Ball: Dragon Daihikyō (SCV) by Epoch was the first game based upon the now long-running manga and anime series, Dragon Ball.[70]

- Dragon Quest (NES) by Chunsoft and Enix introduced the Dragon Quest series in 1986.

- Final Fantasy (NES) by Square started the Final Fantasy series in 1987.

- The Legend of Zelda (NES) by Nintendo EAD and Nintendo initiated the Legend of Zelda series in 1986.

- Mega Man 2 (NES) by Capcom was the breakthrough title in Capcom's Mega Man series. The series had a number of additional hits on the NES, and later spawned several successful spin-off series.

- Metal Gear (MSX2) by Konami initiated the Metal Gear series in 1987. It was released for the MSX2 computer and remade on the NES shortly after.

- Metroid (NES) by R&D1 and Nintendo initiated the Metroid series in 1986.

- Phantasy Star (SMS) by Sega Consumer Development Division 2 and Sega is considered one of the benchmark role-playing video games,[71] and is among the first to use a science fiction setting, and to feature a female protagonist.[72]

- Super Mario Bros. (NES) by Nintendo EAD and Nintendo was bundled with the NES and became the best-selling video game of all time, a title it held until 2009.[73] Countless imitations of the game appeared over the course of the console generation.

- Super Mario Bros. 3 (NES) by Nintendo is widely considered the best sidescrolling platform game of the generation, as well as topping many "Best Game" lists for the NES.[74] Its jumping physics and world map segments, where players can choose their path, served as a formula for later 2D Mario games.

See also

References

- Fahs, Travis. "IGN Presents the History of SEGA: Coming Home". IGN. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- Mark J. P. Wolf (2008), The video game explosion: a history from PONG to Playstation and beyond, ABC-CLIO, p. 115, ISBN 978-0-313-33868-7, retrieved April 19, 2011

- Daglow, Don L. (August 1988). "Over the River and Through the Woods: The Changing Role of Computer Game Designers". Computer Gaming World (50). p. 18.

I'm sure you've noticed that I've made no reference to the Nintendo craze that has repeated the Atari and Mattel Phenomenon of 8 years ago. That's because for American game designers the Nintendo is a non-event: virtually all the work to date has been done in Japan. Only the future will tell if the design process ever crosses the Pacific as efficiently as the container ships and the letters of credit now do.

- Herman 2007, p. 115, 1: "Sega released pair of consoles [..] Nintendo released the Famicom [..] originally intended to be released solely in Japan"

- Herman 2007, p. 115, 2: "approached Atari with the opportunity to license the Famicom"

- Herman 2007, p. 115, 3: "[..] final signings would be made at the CES [..]"

- Herman 2007, p. 115.

- Herman 2007, p. 116, 4: "Atari representatives told Nintendo to clear it up with Coleco"

- Herman 2007, p. 116, 5: "[..] Atari was no longer the threat Nintendo feared [..]"

- Herman 2007, p. 116, 6: "Its controllers used infrared [..] light gun was also going to be sold with the unit"

- Herman 2007, p. 116.

- Herman 2007, p. 116, 7: "The $159 system was released nationally in February 1986"

- Katz, Arnie; Kunkel, Bill; Worley, Joyce (August 1988). "Video Gaming World". Computer Gaming World. p. 44.

- "The Nintendo Threat?". Computer Gaming World. June 1988. p. 50.

- Ferrell, Keith (July 1989). "Just Kids' Play or Computer in Disguise?". Compute!. p. 28. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- Keizer, Gregg (July 1989). "Editorial License". Compute!. p. 4. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- Ferrell, Keith (December 1989). "Epyx Goes Diskless". Compute!. p. 6. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- "Fusion, Transfusion or Confusion / Future Directions In Computer Entertainment". Computer Gaming World. December 1990. p. 26. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- Reeder, Sara (November 1992). "Why Edutainment Doesn't Make It In A Videogame World". Computer Gaming World. p. 130. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- Travis Fahs. "IGN Presents the History of SEGA: World War". IGN. p. 3. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- Altice, Nathan (2015). I Am Error: The Nintendo Family Computer / Entertainment System Platform. MIT Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780262028776.

- 初代「ファミコン」など公式修理サポート終了. ITmedia News (in Japanese). ITmedia. October 16, 2007. Retrieved January 20, 2008.

- RyanDG (October 16, 2007). "Nintendo of Japan dropping Hardware support for the Famicom". Arcade Renaissance. Archived from the original on February 9, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2008.

- Pettus, Sam; Munoz, David; Williams, Kevin; Barroso, Ivan (December 20, 2013). Service Games: The Rise and Fall of SEGA: Enhanced Edition. Smashwords Edition. p. 12. ISBN 9781311080820.

- Plunkett, Luke (January 19, 2017). "The Story of Sega's First Console, Which Was Not The Master System". Kotaku. Gizmodo Media Group. Archived from the original on March 6, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- Wolf, Mark J. P. (2012). Encyclopedia of Video Games: A-L. ABC-CLIO. p. 449. ISBN 9780313379369.

- "Mark III" (in Japanese). Sega Corporation. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- Wardyga, Brian J. (August 6, 2018). The Video Games Textbook: History • Business • Technology. CRC Press. ISBN 9781351172349.

- Sanger, David E. (May 22, 1984). "Atari Video Game Unit Introduced". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- Goldberg, Marty (2012). Atari, Inc. Carmel, NY: Syzygy Co. ISBN 978-0985597405.

- AtariAge: Atari 7800 History, AtariAge.

- "SG-1000" (in Japanese). Sega Corporation. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- Sendov, Blagovest; Stanchev, Ivan (May 17, 2014). Children in the Information Age: Opportunities for Creativity, Innovation and New Activities. Elsevier. p. 58. ISBN 9781483159027.

- Levin, Martin (November 20, 1985). "New components add some Zap to video games". San Bernardino County Sun. p. A-4.

- "Video Robots - The Nintendo Entertainment System, now at Macy's". New York Times. November 17, 1985.

- ACE Magazine- Master System Advert. November 1987. p. 85.

- Linneman, John (July 27, 2019). "Revisiting the Famicom Disk System: mass storage on console in 1986". Eurogamer. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- "Best-Selling Video Games". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on March 17, 2006. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "All Time Top 20 Best Selling Games". May 21, 2003. Archived from the original on February 21, 2006. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Pole Position II for Arcade (1983) - MobyGames". MobyGames (in German). Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- "-Sega Emulation Overview - another overview". Retrocopy.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- "SG-1000 data". Sega.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- Loguidice, Bill; Barton, Matt (February 24, 2014). Vintage Game Consoles: An Inside Look at Apple, Atari, Commodore, Nintendo, and the Greatest Gaming Platforms of All Time. CRC Press. ISBN 9781135006518.

- McAlpine, Kenneth B. (November 15, 2018). Bits and Pieces: A History of Chiptunes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190496098.

- Altice, Nathan (May 2015). I Am Error: The Nintendo Family Computer / Entertainment System Platform. MIT Press. p. 164. ISBN 9780262028776.

- Maxim, Charles MacDonald (November 12, 2005). "SN76489 sightings". SMS Power!.

- Amos, Evan (November 6, 2018). The Game Console: A Photographic History from Atari to Xbox. No Starch Press. p. 68. ISBN 9781593277727.

- "NES Specifications". Problemkaputt.de. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- "RAM - Development - SMS Power!". Smspower.org. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- Charles MacDonald. "Sega Master System VDP documentation". Cgfm2.emuviews.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- "Famitsu August 8, 2013". Sega Consumer 30th Anniversary Book. Famitsu (in Japanese). August 8, 2013. p. 12.

- Espineli, Matt; Thang, Jimmy (July 15, 2019). "Evolution Of Nintendo's Consoles: Switch, Switch Lite, 3DS, Wii, SNES, And More". GameSpot. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- Hugg, Steven (August 8, 2019). Making Games for the NES. Puzzling Plans LLC. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-07-595272-2.

- Wardyga, Brian J. (August 6, 2018). The Video Games Textbook: History • Business • Technology. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-351-17234-9.

- "SEGA MASTER SYSTEM TECHNICAL INFORMATION". Smspower.org.

- "Master System" マスターシステム 各種データ. Sega (in Japanese). Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- Altice, Nathan (May 2015). I Am Error: The Nintendo Family Computer / Entertainment System Platform. MIT Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-262-02877-6.

- D'Argenio, Angelo (January 15, 2018). "Gaming Literacy: An introduction to NES sound and 8-bit sound illusions". Gamecrate. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- "How Sonic Helped Sega to Win the Early 90s Console Wars". Kotaku UK. October 30, 2014. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- "COMPANY NEWS; Nintendo Suit by Atari Is Dismissed". Nytimes.com. May 16, 1992. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- GameSpy Staff (June 13, 2003). "The 25 Dumbest Moments in Gaming". GameSpy. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2018.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Welsh, Oli (February 24, 2017). "A complete history of Nintendo console launches". Eurogamer.net. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- "Consolidated Sales Transition by Region" (PDF). Nintendo. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "NES". Classic Systems. Nintendo. Archived from the original on August 4, 2007. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- Nihon Kōgyō Shinbunsha (1986). "Amusement". Business Japan. Nihon Kogyo Shimbun. 31 (7–12): 89. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- Sheff, David (1993). Game Over (1st ed.). New York: Random House. p. 349. ISBN 0-679-40469-4. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Azevedo, Théo (May 12, 2016). "Console em produção há mais tempo, Master System já vendeu 8 mi no Brasil" (in Portuguese). Universo Online. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

Comercializado no Brasil desde setembro de 1989, o saudoso Master System já vendeu mais de 8 milhões de unidades no país, segundo a Tectoy.

- "Sega Consoles: Active installed base estimates". Screen Digest. Screen Digest. March 1995. p. 60. (cf. here , here , and here )

- Junior Sagster (June 2012). "Alex Kidd - O mascote "renegado" da Sega". Neo Tokyo. Editora Escala (77). ISSN 1809-1784.

- "ラインナップ" ラインナップ ドラゴンボール ゲームポータルサイト バンダイナムコエンターテインメント公式サイト. Dragonball Game Portal (in Japanese). Bandai Namco Entertainment. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- Semrad, Steve (February 2, 2006). "The Greatest 200 Videogames of Their Time". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- Pettus, Sam; Munoz, David; Williams, Kevin; Barroso, Ivan (December 20, 2013). Service Games: The Rise and Fall of SEGA: Enhanced Edition. Smashwords Edition. p. 26. ISBN 9781311080820.

- Iwata, Satoru (June 4, 2009). "Iwata Asks: Wii Sports Resort". Nintendo. p. 4. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

As it's sold bundled with the Wii console outside Japan, I'm not quite sure if calling it "World Number One" is exactly the right way to describe it, but in any case it's surpassed the record set by Super Mario Bros., which was unbroken for over twenty years.

- Gilbert, Henry\ (August 15, 2012). "Why Super Mario Bros 3 is one of the greatest games ever made". GamesRadar. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

Bibliography

- Herman, Leonard (2007). P. J. Wolf, Mark (ed.). A New Generation Of Home Video Game Systems. The Video Game Explosion: A History from PONG to Playstation and Beyond. ISBN 9780313338687.