Typhoon Mangkhut

Typhoon Mangkhut,[nb 1] known in the Philippines as Typhoon Ompong, was an extremely powerful and catastrophic tropical cyclone that caused extensive damage in Guam, the Philippines and South China in September 2018. It was the strongest typhoon to strike Luzon since Megi in 2010, and the strongest to make landfall anywhere in the Philippines since Haiyan in 2013.[2] Mangkhut was also the strongest typhoon to affect Hong Kong since Ellen in 1983.[3]

| Typhoon (JMA scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

Typhoon Mangkhut at peak intensity on September 12 | |

| Formed | September 6, 2018 |

| Dissipated | September 17, 2018 |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 205 km/h (125 mph) 1-minute sustained: 285 km/h (180 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 905 hPa (mbar); 26.72 inHg |

| Fatalities | 134 total |

| Damage | $3.77 billion (2018 USD) |

| Areas affected | Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South China, Vietnam |

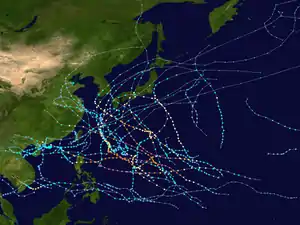

| Part of the 2018 Pacific typhoon season | |

Mangkhut was the thirty-second tropical depression, twenty-second tropical storm, ninth typhoon, and fourth super typhoon of the 2018 Pacific typhoon season. It made landfall in the Philippine province of Cagayan late on September 14, as a Category 5-equivalent super typhoon, and subsequently impacted Hong Kong and southern China.[4] Mangkhut was also the third-strongest tropical cyclone worldwide in 2018.

Over the course of its existence, Mangkhut left behind a trail of severe destruction in its wake. The storm caused a total of $3.77 billion (2018 US) in damage across multiple nations, along with at least 134 fatalities: 127 in the Philippines,[5][6] 6 in mainland China,[7] and 1 in Taiwan.[8]

Meteorological history

On September 5, 2018, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) began monitoring a tropical disturbance near the International Date Line.[9] Steady development ensued over the following days, and the system organized into a tropical depression on September 6, though operationally, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) did not classify the system as a tropical depression until September 7.[10] The depression soon intensified into a tropical storm, upon which it received the name Mangkhut.[11][10] Throughout the next two days, the system underwent rapid intensification. Tight banding features wrapped around a developing eye feature. Favorable environmental conditions hastened Mangkhut's development, including low wind shear, ample outflow aloft, high sea surface temperatures, and high ocean heat content.[12] Mangkhut achieved typhoon strength on September 9.[13][10] A well-defined 18 km (11 mi) eye became evident on satellite imagery as the typhoon approached the Northern Mariana Islands and Guam. The JTWC analyzed Mangkhut as a Category 2-equivalent typhoon with one-minute sustained winds of 165 km/h (105 mph) as it tracked near Rota, around 12:00 UTC on September 10.[14] The JMA assessed the storm's ten-minute sustained winds to be 155 km/h (100 mph) at this time.[15][10]

Substantial intensification ensued on September 11, as Mangkhut traversed the Philippine Sea. A second bout of rapid intensification took place as the storm consolidated significantly; a well-defined 39 km (24 mi) eye became established during this time.[16] The JTWC analyzed Mangkhut to have reached Category 5-equivalent intensity by 06:00 UTC, an intensity it would maintain for nearly four days.[17] The JMA assessed that the typhoon's central pressure bottomed out at 18:00 UTC, with 10-minute sustained winds of 205 km/h (125 mph) and a central minimum pressure of 905 hPa (mbar; 26.73 inHg).[18][10] The JTWC noted additional strengthening on September 12, and assessed Mangkhut to have reached its peak intensity at 18:00 UTC, with one-minute sustained winds of 285 km/h (180 mph).[19] The typhoon made landfall in Baggao, Cagayan at 2:00 a.m. PST on September 15 (18:00 UTC on September 14), as a Category 5-equivalent super typhoon, with 10-minute sustained winds of 205 km/h (125 mph) and 1-minute sustained winds of 260 km/h (160 mph).[2] This made Mangkhut the strongest storm to strike the island of Luzon since Typhoon Megi in 2010, and the strongest nationwide since Typhoon Haiyan in 2013.[20]

Traversing the mountains of Luzon weakened Mangkhut before it emerged over the South China Sea on September 15. The typhoon subsequently made landfall again on the Taishan coast of Jiangmen, Guangdong, China, at 5 p.m. Beijing Time (09:00 UTC) on September 16, with 2-minute sustained winds of 45 m/s (160 km/h) according to China Meteorological Administration.[21][22][23][24]

Following landfall, Mangkhut quickly weakened while moving westward. Late on September 17, Mangkhut dissipated over Guangxi, China.[25]

Preparations

Philippines

Tropical cyclone warning signals were hoisted by the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration as early as September 13. Preemptive and forced evacuations were implemented, especially in the Ilocos, Cagayan Valley and Cordillera administrative regions, the three regions widely expected to be severely affected by Mangkhut (Ompong). School class suspensions were announced as early as September 12 in preparation for the approaching typhoon.[26][27][28][29] Medical and emergency response teams were placed on standby, and ₱1,700,000,000 worth of relief goods were prepared by 13 September.[1]

Highest Public Storm Warning Signal

| PSWS# | LUZON | VISAYAS | MINDANAO |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSWS #4 | Cagayan, northern part of Isabela, Babuyan Group of Islands, Ilocos Norte, Abra, Apayao, Kalinga | NONE | NONE |

| PSWS #3 | Batanes, Ilocos Sur, La Union, Mt. Province, Benguet, Ifuga | NONE | NONE |

| PSWS #2 | southern part of Isabela, Nueva Vizcaya, Pangasinan, Tarlac, Nueva Ecija, Aurora, Zambales, Quirino, Pampanga, Bulacan, northern part of Quezon incl. Polillo Island | NONE | NONE |

| PSWS #1 | Bataan, Rizal, Batangas, Metro Manila, Cavite, Laguna, southern part of Quezon, Lubang Island | NONE | NONE |

Hong Kong

On 12 September, as Mangkhut was forecast to severely threaten Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Government convened an inter-departmental meeting to discuss possible responses to the storm.[30]

On September 14, the Hong Kong Government held a rare cross-department press conference over the preparation for Mangkhut, reminding Hong Kong citizens to "prepare for the worst". That night, the Hong Kong Observatory issued the Standby Signal No. 1 when Mangkhut was 1110 kilometers away from Hong Kong, the farthest distance on record.[31]

On September 15, citizens living in Tai O and Lei Yue Mun were evacuated from these low-lying areas that have historically been very prone to storm surge.[32] Hong Kong Observatory issued Strong Wind Signal No. 3 in the afternoon.[33]

On September 16, as Mangkhut maintained its course towards the Pearl River Estuary, Hong Kong Observatory issued Gale or Storm Signal No. 8 during midnight.[34] After dawn, as local winds rapidly strengthened, Hong Kong Observatory issued Increasing Gale or Storm Signal No. 9.[35] At 9:40 a.m., the Hong Kong Observatory issued the Hurricane Signal No. 10, the highest level of tropical cyclone warning signals in Hong Kong.[36] This marked only the third time that this warning has been issued for the region since 1999, the others being with Typhoon Hato in 2017 and Typhoon Vicente in 2012.[37] The signal was held for 10 hours, the second longest duration ever, only behind the 11 hours during Typhoon York in 1999.[38] The typhoon passed 100 kilometers south of Hong Kong at its closest, the joint farthest for a Hurricane Signal No. 10, with Typhoon Vicente.[39]

Mainland China

On September 15, the meteorological bureaus of most cities in Guangdong issued red alerts for Typhoon Mangkhut, which is the highest level of alerts in Guangdong.[40][41] The Guangxi Meteorological Bureau also issued a red alert for the typhoon at 17:00 Beijing Time.[42] On the next day, the Meteorological Bureau of Shenzhen Municipality issued a red alert for rainstorm, which is the highest level of alerts in Shenzhen.[43][44]

The Fujian Meteorological Bureau issued an orange alert for the typhoon, the second highest alert level, on September 15.[45]

On September 16, National Meteorological Center of CMA renewed a red alert for Typhoon Mangkhut, which is the highest level of alerts in China.[46] On the same day, the Hainan Meteorological Bureau issued an orange alert for the typhoon.[47] In Guangdong's provincial capital Guangzhou, schools, public transportation, and businesses were closed across the entire city for the first time since 1978.[48][49]

Impact

Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands

.jpg.webp)

After the center of Mangkhut passed near Guam, about 80% of the island lost electricity.[50] The typhoon caused $4.3 million in infrastructural damage in Guam.[51]

Philippines

A tornado was reported in Marikina, eastern Metro Manila, on the night around 5:30pm Philippine Standard Time of September 14 (Friday), injuring two people.[52] Over 105,000 families evacuated from their homes,[53] and several airports in northern Luzon closed and airlines cancelled their flights until September 16.[54]

On September 22, the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council confirmed that the typhoon had caused at least 127 fatalities;[5][6] 80 deaths occurred in the collapse of a small mine in the town of Itogon, Benguet, where dozens of landslides buried homes.[55] Philippine police also stated that another 111 people remained missing, as of September 22.[5]

| Rank | Storm | Season | Damage | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHP | USD | ||||

| 1 | Yolanda (Haiyan) | 2013 | ₱95.5 billion | $2.2 billion | [56] |

| 2 | Pablo (Bopha) | 2012 | ₱43.2 billion | $1.06 billion | [57] |

| 3 | Glenda (Rammasun) | 2014 | ₱38.6 billion | $885 million | [58] |

| 4 | Ompong (Mangkhut) | 2018 | ₱33.9 billion | $627 million | [59] |

| 5 | Pepeng (Parma) | 2009 | ₱27.3 billion | $581 million | [60] |

| 6 | Ulysses (Vamco) | 2020 | ₱20.3 billion | $421 million | [61] |

| 7 | Rolly (Goni) | 2020 | ₱20 billion | $369 million | [62] |

| 8 | Pedring (Nesat) | 2011 | ₱15.6 billion | $356 million | [57] |

| 9 | Lando (Koppu) | 2015 | ₱14.4 billion | $313 million | [63] |

| 10 | Frank (Fengshen) | 2008 | ₱13.5 billion | $304 million | [64] |

Francis Tolentino, a political adviser of President Rodrigo Duterte, announced that an estimated 5.7 million people nationwide had been affected by the storm.[65] Luzon suffered extensive losses which more than doubled the expected worst-case scenario outlined by Agriculture Secretary Emmanuel Piñol.

As of October 5, the NDRRMC estimated that Mangkhut caused PHP33.9 billion (US$626.8 million) in damages in the Philippines, with assessments continuing.[66]

Malaysia

The tail winds from Mangkhut also affected some parts of Malaysia (as well as state of Sabah).

Taiwan

A 30-year-old female teacher visiting Fenniaolin Beach in Yilan County was swept out to sea by a wave. Her body was recovered two days later.[67][68]

Hong Kong

Mangkhut was the most intense typhoon to strike Hong Kong since Typhoon Ellen in 1983; the highest typhoon warning signal No. 10 remained in place for 10 hours.[3][69] The typhoon's rainfall and storm surge caused serious flooding, especially in low-lying and coastal areas, while strong winds knocked over more than 47,000 trees, blocking several major roads. An hourly mean wind of 81 km/h and gusts up to 169 km/h were recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory in Tsim Sha Tsui, while on Cheung Chau island these figures reached 157 and 212 km/h respectively. The strongest winds in Hong Kong near sea level were recorded at the remote Waglan Island, with 10-minute sustained winds of 180 km/h gusting up to 220 km/h.[69] These winds caused the territory's many skyscrapers to sway and shattered glass windows; notably, the curtain walls of the Harbour Grand Kowloon were blown out by the winds. A construction elevator shaft on a high-rise under construction in Tai Kok Tsui collapsed onto an adjacent building, which had to be evacuated by police.[70] Many roads were blocked by fallen trees and other debris, including major arteries such as Lockhart Road in Wan Chai and Kam Sheung Road, and service on the Mass Transit Railway (MTR) was halted on all above-ground sections of track.[71][72]

Serious flooding was reported in many seaside residential areas, including Heng Fa Chuen, Tseung Kwan O South, Shek O, Lei Yue Mun, villages in Tuen Mun, and the fishing village of Tai O,[73] due to a powerful storm surge of up to 3.38 metres (11.1 ft).[3] About 1,219 people sought refuge in emergency shelters opened by the Home Affairs Department.[74] The Hong Kong International Airport cancelled and delayed a total of 889 international flights. More than 200 people were injured, but no fatalities were reported.[75][76] Due to the substantial damage and disruption caused by the typhoon, the Education Bureau announced that all schools would be closed on September 17 and 18.[71] Insurance claims in Hong Kong amounted to HK$7.3 billion (US$930 million).[77]

The day after the storm, massive crowds filled the territory's MTR system, which operated at a reduced level of service on some lines as some sections of the tracks had been blocked by debris.[78] Most of the city's 600 bus routes also went out of service due to blocked roads.[79]

Macau

.jpg.webp)

A storm surge of up to 1.9 metres (6 ft 3 in) affected Macau. About 21,000 homes lost power and 7,000 homes lost internet access,[80] and 40 people were injured. For the first time in history, all casinos in Macau were closed.[81] The Macau International Airport cancelled 191 flights on Saturday and Sunday (15 and 16 September).[80] Total damage in Macau was estimated to be 1.74 billion patacas (US$215.3 million).[82]

Mainland China

Typhoon Mangkhut caused the evacuation of over 2.45 million people.[23][24] In Shenzhen, the storm caused power failures in 13 locations, flooded the Seafood Street, and caused 248 tree falls.[83] Transport was shut down in Southern China,[84][85] and at least four people in Guangdong were killed in the typhoon.[86][87] In Guangzhou, markets, schools and public transport were closed or limited in the wake of the storm on Monday, September 17, and residents were requested to minimize non-essential travel. Ferry services from Zhuhai's Jiuzhougang Port to Shenzhen and Hong Kong were suspended indefinitely. The Civil Air Defense Office of Guangzhou Municipality (Municipal Civil Air Defense Office) cancelled the annual air-raid drills scheduled for September 15 to avoid causing panic as Typhoon Mangkhut approached.[88] Schools in Beihai, Qinzhou, Fangchenggang, and Nanning were closed on September 17.[89][90] The trains to Guangxi were also closed on September 17.[91]

In total, the storm killed 6 people and caused CN¥13.68 billion (US$1.99 billion) in damage.[92]

Retirement

After the PAGASA retired the name Ompong for causing more than ₱1 billion in damage. It was replaced with the name Obet.

Due to the damage and high death toll in Luzon, the name Mangkhut was officially retired during the 51st annual session of the ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee in February 2019. In July 2020, the Typhoon Committee subsequently chose Krathon as its replacement name.[93]

See also

- Typhoons in the Philippines

- Typhoon Wanda (1962) – Strongest typhoon recorded in Hong Kong

- Typhoon Hope (Ising; 1979) – One of the strongest typhoons that made its final landfall near Hong Kong.

- Typhoon Ellen (Herming; 1983) – A powerful typhoon that took a similar track through the Philippines in September 1983, and one of the strongest typhoon in Hong Kong

- Typhoon Zeb (Iliang; 1998) – An extremely powerful typhoon that made landfall in the same province of the Philippines

- Typhoon Megi (Juan; 2010) – Another powerful typhoon that made landfall in nearby Isabela province and affected South China and Taiwan

- Typhoon Kalmaegi (Luis; 2014) – A weaker typhoon which made landfall in the same provinces that Mangkhut did, around the same time in 2014

- Typhoon Haima (Lawin; 2016) – Similarly powerful typhoon which also made landfall in Cagayan

- Typhoon Hato (Isang; 2017) – Most recent typhoon to affect Hong Kong and Macau prior to Mangkhut

Notes

- "Mangkhut" (Thai pronunciation: [māŋ.kʰút]) is the Thai name for the mangosteen.[1]

References

- "Philippines starts evacuations along coast as Super Typhoon Mangkhut nears". Channel NewsAsia. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- James Griffiths; Steve George; Jo Shelley (15 September 2018). "Philippines lashed by Typhoon Mangkhut, strongest storm this year". Cable News Network. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Cheung, Tony; Xinqi, Su. "Typhoon Mangkhut officially Hong Kong's most intense storm since records began". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "Year's strongest storm batters Philippines". 15 September 2018 – via www.bbc.com.

- Girlie Linao (22 September 2018). "Typhoon Mangkhut death toll hits 127". PerthNow. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "At least 95 dead due to Typhoon Ompong". Rappler. 21 September 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- 应急管理新机制助力台风"山竹"应对 (Report) (in Chinese). 19 September 2018. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- McKenzie, Sheena. "Typhoon Mangkhut hits mainland China, lashes Hong Kong, dozens dead in Philippines". Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Significant Tropical Weather Outlook for the Western and South Pacific Oceans (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 5 September 2018. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "bst2018.txt". Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Tropical Cyclone Advisory (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. 7 September 2018. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Prognostic Reasoning for TY 26W (Mangkhut) Warning NR 09 (Technical Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 9 September 2018. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Tropical Cyclone Advisory (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. 9 September 2018. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Prognostic Reasoning for TY 26W (Mangkhut) Warning NR 15 (Technical Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 10 September 2018. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Tropical Cyclone Advisory (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. 10 September 2018. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Prognostic Reasoning for TY 26W (Mangkhut) Warning NR 18 (Technical Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 11 September 2018. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Prognostic Reasoning for STY 26W (Mangkhut) Warning NR 19 (Technical Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 11 September 2018. Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Tropical Cyclone Advisory (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. 11 September 2018. Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Prognostic Reasoning for STY 26W (Mangkhut) Warning NR 24 (Technical Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 12 September 2018. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- James Griffiths, Steve George, and Jo Shelley (15 September 2018). "Philippines lashed by Typhoon Mangkhut, strongest storm this year". CNN. Retrieved 16 September 2018.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Typhoon Mangkhut, as severe typhoon, made landfall in coast of Jiangmen, Guangdong". China Meteorological Administration. 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Yamei, ed. (16 September 2018). "Super Typhoon Mangkhut lands on south China coast". Xinhuanet. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- Liangyu, ed. (16 September 2018). "Super Typhoon Mangkhut lands on south China coast". Xinhuanet. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- 毛思倩 (16 September 2018). 韩家慧; 聂晨静 (eds.). "强台风"山竹"登陆广东". Xinhuanet (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "It then moved into western part of Guangdong and weakened further. Mangkhut degenerated into an area of low pressure over Guangxi the next night". Hong Kong Observatory. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "September 12 2018: Walang Pasok". Rappler. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Walang Pasok: Class suspensions for September 13". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Walang Pasok: Class suspensions for September 14". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Walang Pasok: Class suspensions for September 15". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Hong Kong braces itself for Super Typhoon Mangkhut, the strongest tropical storm in decades". Channel NewsAsia. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "the Hong Kong Observatory issued the Standby Signal No. 1 well in advance at 10:20 p.m. on 14 September when Mangkhut was about 1 110 km east-southeast of the territory, the farthest distance on record". Hong Kong Observatory. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "Home Affairs Department prepares for approach of tropical cyclone". The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region - Press Releases. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "the No. 3 Strong Wind Signal was issued at 4:20 p.m. on 15 September when Mangkhut was about 650 km southeast of Hong Kong". Hong Kong Observatory. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "With Mangkhut maintaining its course towards the Pearl River Estuary, the Observatory issued the No. 8 Northeast Gale or Storm Signal at 1:10 a.m. on 16 September when Mangkhut was about 410 km southeast of the territory". Hong Kong Observatory. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "the Increasing Gale or Storm Signal No. 9 was issued at 7:40 a.m. when Mangkhut was about 200 km south-southeast of the territory". Hong Kong Observatory. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "the Observatory issued the Hurricane Signal No. 10 at 9:40 a.m. when Mangkhut was about 160 km south-southeast of the territory". Hong Kong Observatory. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "Mangkhut latest: signal No 10 raised as Hong Kong braces for waves up to 14m". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "the Hurricane Signal No. 10 was issued again during the passage of Mangkhut and lasted for ten hours. It was the second longest duration of Signal No. 10 since World War II, just after the 11 hours of York in 1999". Hong Kong Observatory. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "Mangkhut came closest to the Hong Kong Observatory Headquarters around 1 p.m. with its centre was located about 100 km to the south-southwest". Hong Kong Observatory. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Phoebe Zhang; Sarah Zheng (16 September 2018). "Super Typhoon Mangkhut brings back bad memories for people of southern China's Guangdong". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- 王星; 陈育柱, eds. (16 September 2018). "深圳发布台风红色预警,全市范围内实行"四停"". 人民网 (in Chinese). 深圳特区报. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "广西气象台发布今年首个台风红色预警". 网易新闻 (in Chinese). 老友网. 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- 吕绍刚; 夏凡 (16 September 2018). "深圳市暴雨橙色预警升级为红色". 搜狐网 (in Chinese). 人民网. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Han Ximin (17 September 2018). "STRONGEST-IN-DECADES TYPHOON WREAKS HAVOC IN SZ". Shenzhen Daily. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- 林峰峰 (15 September 2018). 孙劲贞 (ed.). "福建发布台风橙色预警 今明两天全省多地有大到暴雨". 东南网 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ZX, ed. (16 September 2018). "China renews red alert for Typhoon Mangkhut". Xinhuanet. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "海南省气象台9月16日6时发布橙色台风预警 台风将于下午到夜间在广东珠海到吴川一带沿海登陆". 海南新闻-海南新闻中心-海南在线 海南一家 (in Chinese). 海南省气象台. 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "关于立即执行停市的紧急通知". Guangzhou People's Government (in Chinese). 广州市防汛防旱防风总指挥部. 16 September 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- "商务委:首次停市平稳有序 市民:学到了防台风技能". Sina (in Chinese). 大洋网. 18 September 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- Eugenio, Haidee V (11 September 2018). "Homes, roads, power system damaged by Mangkhut. Guam poised to ask Trump for emergency declaration". Pacific Daily News.

- Babauta, Chloe B. (27 September 2018). "Typhoon Mangkhut cost GovGuam $4.3 million; no guarantee of federal aid". Pacific Daily News. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- "Buhawi nanalasa sa Marikina; 2 residente nakuryente". ABS-CBN News (in Tagalog). 14 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "'Ompong' weakens anew, to leave PAR Saturday night". The Philippine Star.

- "Ompong shuts down several north Luzon airports". ABS-CBN News.

- "Typhoon Mangkhut: More Than 40 Bodies Found in Philippines Landslide". The New York Times. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- del Rosario, Eduardo D. (April 2014). FINAL REPORT Effects of Typhoon YOLANDA (HAIYAN) (pdf) (Report). NDRRMC. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Uy, Leo Jaymar G.; Pilar, Lourdes O. (8 February 2018). "Natural disaster damage at P374B in 2006-2015". PressReader. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Ramos, Benito T. (16 September 2014). FINAL REPORT re Effects of Typhoon (pdf) (Report). NDRRMC. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- Jalad, Ricardo B. (5 October 2018). Situational Report No.55 re Preparedness Measures for TY OMPONG (I.N. MANGKHUT) (pdf) (Technical report). NDRRMC. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Rabonza, Glenn J. (20 October 2009). FINAL Report on Tropical Storm \"ONDOY\" {KETSANA} and Typhoon \"PEPENG\ (pdf) (Report). NDRRMC. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- Jalad, Ricardo B. (6 December 2020). "SitRep no. 26 re Preparedness Measures and Effects for Typhoon Ulysses (I.N. VAMCO)" (PDF). ndrrmc.gov.ph. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- Jalad, Ricardo B. (10 November 2020). "SitRep No.11 re Preparedness Measures for Super Typhoon Rolly" (PDF). NDRRMC. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Pama, Alexander P. FINAL REPORT re Preparedness Measures and Effects of Typhoon LANDO (KOPPU) (pdf) (Report). NDRRMC. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- Ramos, Benito T. (31 July 2008). Situation Report No. 33 on the Effects of Typhoon “FRANK” (Fengshen) (pdf) (Technical report). NDCC. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- "Typhoon Mangkhut: At Least 43 Bodies Found in Philippines Landslide". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "Situational Report No.55 re Preparedness Measures for TY OMPONG (I.N. MANGKHUT)" (PDF). NDRRMC. 5 October 2018.

- "'Ompong,' strongest storm this year, has passed but monsoon rains to continue". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Matthew Strong (15 September 2018). "Body of woman swept away by waves found on Taiwan east coast beach". Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- "TYPHOONS WHICH REQUIRED THE HURRICANE SIGNAL NO. 10 SINCE 1946". Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- Cheng, Kris (16 September 2018). "Video: Construction elevator shaft falls from building as typhoon Mangkhut rips through Hong Kong". Hong Kong Free Press.

- "(Mangkhut) Classes to remain suspended". The Standard. 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Kao, Ernest; Zhao, Shirley; Ng, Naomi; Sum, Lok Kei (29 September 2018). "Hong Kong begins slow recovery after Typhoon Mangkhut batters city". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "Typhoon Mangkhut: Serious flooding and swaying buildings as Hongkongers battle monster storm". SCMP. 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "Tropical Cyclone Mangkhut situation report (5)". Hong Kong Government. 16 September 2018.

- Jane Cheung; Sophie Hui (17 September 2018). "Monstrous Mangkhut: Super typhoon leaves more than 200 injured and paralyzes transport as it pummels Hong Kong with record-breaking winds". The Standard. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- "Typhoon Mangkhut: Deadly typhoon lands in south China". BBC News. 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- Denise Tsang; Enoch Yiu; Tony Cheung (17 September 2018). "Typhoon Mangkhut bill could set Hong Kong record of US$1 billion in insurance claims". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Cheng, Kris (17 September 2018). "Crowds and frustration at transport hubs as Hongkongers return to work after Typhoon Mangkhut". Hong Kong Free Press.

- Xinqi, Su (17 September 2018). "Typhoon Mangkhut travel chaos: how one woman's Hong Kong commute took more than two hours and a trip in the wrong direction". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Sum, Lok-kei (16 September 2018). "Typhoon Mangkhut: 20,000 Macau households left without power after monster storm causes severe flooding in casino hub". South China Morning Post.

- "Typhoon lashes south China after killing dozens in Philippines". Associated Press. 16 September 2018.

- Moura, Nelson (9 May 2019). "Typhoon Mangkhut to have caused MOP 1.74 bln in economic losses to the city". Macau Business. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- Richard Han (17 September 2018). "Mangkhut wreaks havoc on SZ". Shenzhen Daily. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "Typhoon Mangkhut: South China battered by deadly storm". BBC News. 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- He Huifeng; Phoebe Zhang (16 September 2018). "Southern China's Pearl River Delta shuts down as Typhoon Mangkhut kills at least two in Guangdong". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- 李琪, ed. (17 September 2018). "应急管理部:台风"山竹"致广东4人死亡,具体灾情仍在统计". 澎湃新闻 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- Phoebe Zhang; Matt Ho (17 September 2018). "Typhoon Mangkhut: four dead in southern China, residents warned to remain alert". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "广州市人民政府门户网站 - 关于取消2018年9月15日防空警报试鸣的紧急通知". www.gz.gov.cn (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- "红色预警!风王"山竹"携狂风暴雨杀到 钦北防停课_网易订阅". NetEase (in Chinese). 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "紧急通知!南宁各级各类学校、幼儿园9月17日停课1天_网易新闻". NetEase (in Chinese). 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "受台风影响 16日两广间跨省高铁全停运_网易订阅". NetEase (in Chinese). 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- CMA (4 December 2018). Member Report: China (PDF). ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee. ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- "Replacement Names of MANGKHUT and RUMBIA in the Tropical Cyclone Name List" (PDF). ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee. 17 February 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Typhoon Mangkhut (2018). |

- "Typhoon Mangkhut". Digital Typhoon. NII. Typhoon 201822.

- "Typhoon Mangkhut" (pdf). Best track data (in Japanese). JMA.

表は、後解析が終わり次第掲載します。[The table will be posted as soon as the post analysis is over]

- "Typhoon Mangkhut". Imagery. NRL. 26W Mangkhut.

- EMSR312: Super Typhoon Mangkhut over the Northern Philippines (damage assessment maps) – Copernicus Emergency Management Service

- EMSR310: Tropical Cyclone MANGKHUT-18 in Northern Mariana Islands and Guam (delineation maps) – Copernicus Emergency Management Service