Uns ist ein Kind geboren, BWV 142

Uns ist ein Kind geboren (Unto us a child is born), BWV 142 / Anh. II 23, is a Christmas cantata by an unknown composer.[1][2] In the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis it is listed among the works with a doubtful attribution to Johann Sebastian Bach.[3] The text is based on a libretto by Erdmann Neumeister first published in 1711. Although attributed to Bach by the Bach-Gesellschaft when they first published it in the late nineteenth century, that attribution was questioned within thirty years and is no longer accepted. Johann Kuhnau, Bach's predecessor as Thomaskantor in Leipzig, has been suggested as the probable composer, but without any certainty.

The cantata is in eight movements, and is scored for vocal soloists, choir, recorders, oboes, strings and continuo.

History, authenticity and attribution

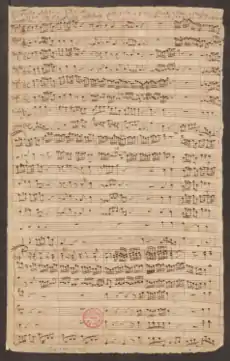

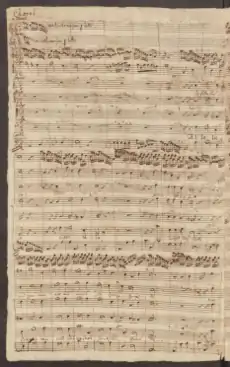

The biblical text, chorale and free verse come from the 1711 collection of librettos of the writer, theologian, pastor and theorist, Erdmann Neumeister.[5] A libretto, based on Neumeister's text, survives in the Stadtgeschichtliches Museum, Leipzig for a cantata with this title. The cantata was listed to be performed in both of the main churches in Leipzig—the Thomaskirche and Nikolaikirche—on Christmas Day 1720, during the period when Johann Kuhnau was Thomaskantor. The earliest surviving manuscript copy of BWV 142 made by Christian Friedrich Penzel in Leipzig on 8 May 1756 is also based on Neumeister's text. Penzel credited J.S. Bach as the author in the heading of the sinfonia on the first page of the manuscript; and he signed the last page, giving the date and place. Differences between the 1720 and 1756 librettos and Neumeister's original text are discussed by Glöckner (2000), but it has not been possible to determine whether the 1756 cantata is a subsequent reworking of the 1720 cantata.[6]

Around the 1830s Franz Xaver Gleichauf made a hand copy of the score of the BWV 142 cantata, without mentioning a composer in his manuscript.[7][3] In 1843 the Penzel manuscript was copied in Vienna.[8][9] Another copy of the cantata, made around the same time, was later owned by Johann Theodor Mosewius, who listed Uns ist ein Kind geboren as one of five Christmas cantatas by Bach in an 1845 publication.[10][11][12] 19th-century Bach-biographies by Hilgenfeldt (1850), Bitter (1865), Spitta (1873), and Lane Poole (1882) mention Uns ist ein Kind geboren as a cantata composed by Bach.[13][14][15][16]

In 1873, before questions of authenticity had been raised, Philipp Spitta devoted 18 pages of his two-volume biography of Bach to a comparison of Bach and Telemann cantatas that set the same Neumeister text:[17] Spitta's commentary—praising Bach's music while disparaging Telemann's—was typical of musical criticism in the late nineteenth century.[18][19][20] Spitta compares the BWV 142 cantata with TVWV 1:1451,[21] a cantata by Telemann on the same libretto by Neumeister: he is fairly dismissive about the Telemann composition ("... probably written in half-an-hour ...", "... shows us the worst side of the church music of the time ..." etc.), only finding a few places where Telemann's composition compares favourably to the composition he attributes to Bach.[15][22] According to Spitta, Bach "adhered throughout the cantata to the subdued minor key, which offers so singular a contrast to the bright joyfulness of Christmas. It gives a tone as of melancholy reminiscences of the pure Christmas joys of our childhood ...; in contrast to this Telemann's eternal C major is often unutterably shallow and flat."[22][15]

The cantata was first published as a work of Bach in 1884 by the Bach-Gesellschaft, with Paul Waldersee as editor.[5][23] After subsequent commentary by Bach scholars Johannes Schreyer, Arnold Schering and Alfred Dürr, that attribution was no longer generally accepted, although the identity of the original composer has not so far been established with certainty. After Schreyer and Schering had cast doubts in 1912–1913 on authorship by Bach, Dürr subjected the cantata in 1977 to the same detailed and rigorous musical analysis as all the other cantatas of Bach. Having established that, if by Bach, the cantata could only have been composed in 1711–1716 during Bach's period in Weimar, Dürr ruled out authorship by Bach based on the presence of uncharacteristic stylistic features (such as the restricted range of the vocal part in the recitative; excessive homophony in the choruses; two obbligato instruments and over-frequent instrumental episodes in the arias, with the solo voice dominating and the instruments consigned to an imitative decorative role), as well as the absence of characteristic elements (such as permutation fugues in choruses; balanced concertato alternation between solo voices and instruments in arias; ostinato-type forms in arias and ritornellos).[24][25]

According to David Erler, writing in the program notes of a 2015 concert, the cantata has been widely attributed to Kuhnau.[26] Schering had suggested Kuhnau as the possible composer of the cantata in the Bach-Jahrbuch of 1912.[24][27] Five years later he retracted that suggestion, then thinking it more likely that the cantata was written by one of Kuhnau's students.[28] In the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis of 1998, the cantata is listed in Anhang II, the annex of doubtful works.[27][29] According to the critical commentary of the New Bach Edition, written by Andreas Glöckner, possible problems with the attribution to Kuhnau arise from differences between the surviving 1720 Leipzig libretto for Kuhnau's cantata and the text in Penzel's version; with the modernity of the opening sinfonia, which departs from Kuhnau's more conservative style; and from the absence in Penzel's version of trumpets and drums, instruments traditionally used in the two main churches of Leipzig for Christmas Day cantatas.[30]

Movements

The cantata is scored for three vocal soloists (alto, tenor and bass), a four-part choir, two alto recorders, two oboes, two violins, viola and continuo.[31]

The piece has eight movements:[32]

- Sinfonia, an instrumental concerto for two alto recorders, two oboes and strings.

- Chorus: Uns ist ein Kind geboren (For unto us a child is born), a double fugue with the first theme set to the text "Uns ist ein Kind geboren" and the second set to "Eins Sohn ist uns gegeben".

- Aria (bass): Dein Geburtstag ist erschienen (So appears the Natal day). In this aria in E minor the bass is accompanied by two obbligato violins and continuo.

- Chorus: Ich will den Namen Gottes loben (I will praise the name of God). This short choral movement begins with a fugato section in which the four vocal parts are accompanied by the first and second violins. After the fugal entries, the music is homophonic.

- Aria (tenor): Jesu, dir sei Dank (Jesus, thanks be to you). In this relatively short da capo aria, the tenor is accompanied by two obbligato oboes.

- Recitative (alto): Immanuel (Emmanuel!)

- Aria (alto): Jesu, dir sei Preis (Praise be to you, Jesus). Set to new words, this aria is a transposition of the 5th movement from A minor to D minor, with the alto replacing the tenor and the two alto recorders replacing the oboes.

- Chorus: Alleluia. Over an almost uninterrupted stream of semiquaver figures played in unison by alto recorders, oboes and violins, the choir sings the final four-part chorale line by line.

Translations

In 1939, Sydney Biden provided the English translation for the cantata For us a child is born.[33]

Arrangements

In 1940, William Walton orchestrated the first bass aria in the cantata as dance music for Frederick Ashton's ballet The Wise Virgins.[34] Arrangements of the final chorus for organ and one or more brass instruments have been published separately.[35]

Recordings

Recordings of the cantata include:

- Alsfelder Vokalensemble / I Febiarmionici, Wolfgang Helbich. The Apocryphal Bach Cantatas II. CPO, 2001.

- Choir and Orchestra "Pro Arte" Munich, Kurt Redel. J. S. Bach: Magnificat in D Major & Cantata BWV 142. Philips, 1964.

- Mannheim Bach Choir / Heidelberger Kammerorchester, Heinz Markus Göttsche. J. S. Bach: Cantatas BWV 62 & BWV 142. Da Camera, 1966.

- Capella Brugensis / Collegium instrumentale Brugense, Patrick Peire. 'Uns ist ein Kind geboren', Eufoda, 1972

Notes

- Work 00174 at Bach Digital website. 10 April 2017.

- RISM No. 467300002

- RISM No. 220036186

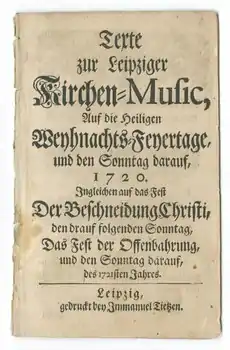

- Glöckner 2000, p. 118 The title page reads: Texte | zur Leipziger | Kirchen Music, | auf die Heiligen | Weynachts-Feyertage, | und den Sonntag darauf, | 1720. | Ingleichen auf das Fest | Der Beschneidung Christi, | den darauf folgenden Sonntag, | Das Fest der Offenbahrung, | und den Sonntag darauf, | des 1721sten Jahres. | Leipzig, | gedruckt bey Immanuel Tietzen.

- Glöckner 2000, p. 117

- See:

- Glöckner 2000

- Dürr 1977, p. 57

- Buelow 2001

- Palisca, Claude V. (1991), Baroque Music (3rd ed.), Prentice-Hall, p. 321

- Küster 1999

- D-HAmi Ms. 165 at Bach Digital website

- D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 464, Fascicle 1 at Bach Digital website

- Waldersee 1884, pp. XV–XXI.

- PL-Wu RM 5908, Fascicle 5 at Bach Digital website

- RISM No. 300512416

- Mosewius 1845, p. 20

- Hilgenfeldt 1950, p. 99

- Bitter 1865, Vol. II p. XCVII

- Spitta 1873, pp. 480–485 and endnote 21 pp. 797–798 (English translation: Spitta 1899, Vol. I, pp. 487–491 and endnote 20 pp. 630–631)

- Lane Poole 1882, p. 131

- Talle 2013, p. 50

- Buelow 2004, pp. 566–567

- Zohn 2001, see

- For further commentary on Spitta's comparison of Telemann and Bach, see also

- Hirschmann 2013, p. 6

- Payne 1999, p. 4

- Swack 1992, p. 139

- Swack 1992, p. 139.

- Sandberger 1997, pp. 188–189

- Waldersee 1884

- Schering 1913, p. 133.

- See:

- Dürr 1977, pp. 209–211

- Dürr 2006

- "Uns ist ein Kind geboren". Bach Digital (in German). Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- Erler 2015.

- Simon Crouch. Uns ist ein Kind geboren (Unto us a child is born): Cantata 142. Classical Net, 1998.

- Schering 1918, p. XLIV.

- Schmieder, Dürr, and Kobayashi 1998, p. 459.

- Glöckner 2000.

- "Cantata BWV 142 Uns ist ein Kind Geoboren". Bach Cantatas Website. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- See:

- Zedler 2009

- Whittaker 1959, pp. 160–161

- "Bach Bibliography".

- Boyd 1999

- Laster 2005, p. 11.

References

- Bitter, Karl Hermann. Johann Sebastian Bach. Berlin: Schneider, 1865. Vol. 1 – Vol. 2 (in German)

- Boyd, Malcolm (1999), "The Wise Virgins", in Malcolm Boyd (ed.), Bach, Oxford Composer Companion, Oxford University Press

- Buelow, George J. (2001), "Johann Kuhnau", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.15642

- Daniels, David (2005). Orchestral Music: A Handbook. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 146166425X.

- Dürr, Alfred (1977), Studien über die frühen Kantaten Johann Sebastian Bachs (in German) (2nd ed.), Breitkopf & Härtel, pp. 57–58, 209–211, ISBN 3765101303

- Dürr, Alfred (2006), "Appendix: doubtful and spurious cantatas", The cantatas of J. S. Bach, translated by Richard Douglas P. Jones, Oxford University Press, p. 926, ISBN 0-19-929776-2

- Erler, David (2015), "Johann Kuhnau" (PDF), Abendmusiken in der Predigerkirche, pp. 8–9, retrieved 23 January 2017

- Glöckner, Andreas (2000), Johann Sebastian Bach, Varia: Kantaten, Quodlibet, Einzelsätze, Bearbeitungen. Critical commentary, Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke (NBA) (in German), I/41, Bärenreiter, pp. 117–118

- Hilgenfeldt, Carl L. Johann Sebastian Bach's Leben, Wirken und Werke: ein Beitrag zur Kunstgeschichte des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts. Leipzig: Friedrich Hofmeister, 1850 (in German)

- Küster, Konrad (1999), "Erdmann Neumeister", in Malcolm Boyd (ed.), Bach, Oxford Composer Companion, Oxford University Press, pp. 314–315

- Lane Poole, Reginald. Sebastian Bach. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, 1882.

- Laster, James (2005). Catalogue of Music for Organ and Instruments. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810852993.

- Johann Theodor Mosewius, Johann Sebastian Bach in seinen Kirchen-Cantaten und Choralgesängen. Berlin: T. Trautwein, 1845.

- Sandberger, Wolfgang. Das Bach-Bild Philipp Spittas: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Bach-Rezeption im 19. Jahrhundert. Vol. 39 of supplement to the Archiv für Musikwissenschaft, ISSN 0570-6769. Franz Steiner Verlag, 1997. ISBN 9783515070089 (in German)

- Schering, Arnold (1913). Neue Bachgesellschaft. "Beiträge zur Bachkritik" [Contributions to Bach-criticism]. Bach-Jahrbuch (in German). Breitkopf & Härtel. 1912 (9): 124–133. doi:10.13141/bjb.v1912.

- Schering, Arnold (1918). "Vorwort". Sebastian Knüpfer, Johann Schelle, Johann Kuhnau: Ausgewählte Kirchenkantaten. Denkmäler deutscher Tonkunst: Erste Folge (in German). 58–59. Breitkopf & Härtel. pp. V–LII.

- Schmieder, Wolfgang, Alfred Dürr, and Yoshitake Kobayashi (eds.). 1998. Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis: Kleine Ausgabe (BWV2a). Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel. ISBN 978-3765102493.(in German)

- Spitta, Philipp. Johann Sebastian Bach, Erster Band. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1873. (in German)

- Spitta, Philipp, translated by Clara Bell and J. A. Fuller Maitland. Johann Sebastian Bach: His Work and Influence on the Music of Germany, 1685–1750 in three volumes. Novello & Co, 1884–1885. Vol. 1 (1899 edition)

- Swack, Jeanne (1992), "Telemann Research Since 1975", Acta Musicologica, 64 (2): 139–164, doi:10.2307/932913, JSTOR 932913

- Terry, C. S. (1920). "Appendix III: The Bachgesellschaft Editions of Bach's Works", pp. 225–286 in Johann Sebastian Bach: His Life, Art, and Work. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe; London: Constable

- Unger, Melvin P. (1996). Handbook to Bach's Sacred Cantata Texts: An Interlinear Translation with Reference Guide to Biblical Quotations and Allusions. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 1461659051.

- Waldersee, Paul Graf von, ed. (1884), "Cantate Am ersten Weinachtsfesttage: 'Uns ist ein Kind geboren', N° 142", Joh. Seb. Bach's Kirchenkantaten: fünfzehnter Band – N°. 141–150, Johann Sebastian Bach's Werke: Herausgegeben von der Bach-Gesellschaft zu Leipzig (in German), 30, Breitkopf & Härtel, pp. 17–42 (and "Vorwort" pp. XV–XXI)

- Whittaker, William Gillies (1959), The Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach: sacred and secular, Volume I, Oxford University Press

- Zedler, Günther (2009), Die erhaltenen Kantaten Johann Sebastian Bachs (Spätere Sakrale- und Weltliche Werke): Besprechungen in Form von Analysen - Erklärungen - Deutungen (in German), Perfect Paperback, pp. 297–298, ISBN 978-3839137734