Arisierpeton

Arisierpeton is an extinct genus of synapsids from the Early Permian Garber Formation (Sumner Group) of Richards Spur, Oklahoma. It contains a single species, Arisierpeton simplex.[1]

| Arisierpeton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Premaxilla of the holotype specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | †Caseasauria |

| Family: | †Caseidae |

| Genus: | †Arisierpeton Reisz, 2019 |

| Species: | †A. simplex |

| Binomial name | |

| †Arisierpeton simplex Reisz, 2019 | |

Etymology

The generic name honours Mr. Giuseppe Alberto Arisi, who found the material. The specific epithet refers to the relatively simpler morphology of the marginal dentition than in other Permian caseids.[1]

Description

The holotype, GAA 00225-1, is a nearly complete right premaxilla. Several other specimens have been referred including: GAA 00242, a right premaxilla; GAA 00239, a right premaxillary fragment; GAA 00207, a left maxillary fragment; GAA 00225-2, a right maxillary fragment; GAA 00240, a left maxillary fragment with two teeth and fragments of two other teeth; GAA 00246-1, a partial left dentary with eight teeth; GAA 00246-2, a partial right dentary with 12 teeth or parts of teeth and GAA 00244, a series of three dorsal vertebrae. [1]

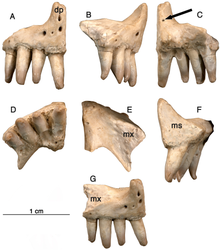

Premaxilla

The premaxilla show some similarities with Oromycter, another species of caseid from Richards Spur, including the presence of a massive, thick dorsal or nasal process, a small vomerine or palatal process, broad central portion, and a wide maxillary process with a large dorsally located sutural surface for the anterior process of the maxilla. The premaxilla also bears an anteriorly tilted dorsal or nasal process which is a key characteristic of Caseidae.[1]

There is also a foramen that opens dorsally at the base of the dorsal process which is substantially larger in Oromycter. An autapomorphy of Arisierpeton is the presence of four premaxillary teeth all of the same size unlike most other caseasaurs, which have three or two premaxillary teeth, often with the first tooth being the largest tooth in the marginal dentition.[1]

Maxillae

The maxillary dorsal process may have been slenderly built, and is similar in some respects to the observed anatomy in Oromycter. A modest anterodorsal process of the maxilla, is present at the level of the internal narial border of the bone medially. The dorsal terminus is broken in the more complete maxillary fragment, making it difficult to determine its original height. In contrast to Oromycter, the preserved base of the narial border of the dorsal process is wide and rounded, suggesting that an anterior maxillary shelf may have been present on the complete maxilla, the shape of the maxilla in this region also suggests that there may have been one. The morphology of the maxilla represents a more derived condition than that seen in Oromycter, where the anterior edge of the dorsal process is a sharp ridge, and the distinctive anterolateral narial shelf is restricted to the lacrimal bone. On the anterior lateral surface of the maxilla a single large anteriorly oriented foramen is present in Arisierpeton, instead of a series of relatively large labial foramina situated along the external surface of the bone. External surface sculpturing is also more modest than in Oromycter and is restricted to faint grooves associated with small foramina on the surface of the bone.[1]

Dentary

Assignment of two dentaries to a caseid is based on the shape of the symphyseal area. As in other caseids, the dorsal edge of the dentary bone curves ventrally near the symphysis, and forms an acute angle with the ventral edge of the bone. This results in a substantially more slender dentary bone near the symphysis than in the rest of the bone. As in other caseids, this is related to the presence of a well-developed anterior process of the splenial bone, one that contributes to a large portion of the symphysis medially. Although the dentary bones assigned are nearly complete anteriorly, their morphology cannot confirm the entire depth or height of the lower jaw at the symphysis. This is because the dentary contributes only to the dorsal half of the symphysis in caseids, and the splenial most likely contributed to the symphysis, as it formed the lower part of the symphyseal region of the mandible. The assignment of these dentaries to Arisierpeton is based mainly on dental features, and to some extent on the labial surface characteristics of the bone. The teeth of these dentaries are identical to those found on the maxillae. In addition, the surface characteristics of the labial side of the dentaries are similar to those of the maxillae, showing little sculpturing, and occasional small foramina. A well-developed, anteriorly extending Meckelian canal is formed by the dentary bone, below which it would be attached to the splenial by sutures.[1]

Dentition

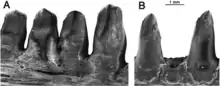

Most of the premaxillary teeth on all the known specimens are damaged near their tips but show clear evidence of tapering crownward. However, all of the preserved teeth also show that they are somewhat spatulate towards the tip of the crown and are unlikely to have had a pointed apex.[1]

Most maxillary teeth are damaged in some way. Unfortunately, the preserved maxillary tooth rows are too short to determine if heterodonty was present. All the teeth show the typical caseid morphology of having lingually curved crowns, with little or no recurvature. An un-erupted tooth is preserved in the partially resorbed tooth in GAA 00240. As is typical of teeth in their early stages of development, prior to implantation, only the enamel cap is preserved, a simple conical structure. Although difficult to discern, a small secondary cusp is present along the posterior edge of the cap. The tooth immediately anterior to this un-erupted tooth has a similar superficial morphology as those on the premaxilla, with vertical fluting lingually on the enamel surface. Unfortunately, most of the teeth have lost their crown tips, making it difficult to determine if they were also tricuspid. However, the arrangement of the fluting suggests that there also was a central cone in these teeth and possibly two accessory cusps, or at least incipient accessory cusps.[1]

The anterior teeth of the dentary lean forward, as in all caseids. The intact teeth in GAA 00246-2 are smaller than the teeth anterior and posterior to them, and they carry the same kind of vertical fluting lingually as seen in the upper teeth. The apex of each tooth carries anterior and posterior carinae, with a slight hint of an accessory cusp associated with the fanning of the anterior fluting from the central cone of tooth. There is no evidence of a posterior cusp where the fluting extends to the posterior carina. These teeth also appear to have a slightly posteriorly tilted central cone, but in typical caseid fashion there is clear evidence of a pronounced lingual tilt to the crown. As far as can be determined, all of the dentary teeth conform to this pattern, although one tooth at tooth position 8 in GAA 00246-1, although slightly damaged at the tip, does appear to have both anterior and posterior cusps. In all cases the teeth are more slender than in the dentaries of Oromycter and have more modest lingual shoulders at the base of the crown. [1]

Overall, it appears that the dentition in Arisierpeton shows some modifications in tooth shape and crown outline from the primitive amniote condition seen in the basal caseid Eocasea and in eothyridid caseasaurians. The teeth show little or no recurvature, but instead have some medial or lingual curvature apically. The crowns, when preserved, show some fluting and occasional carinae, which are sometimes sufficiently well developed for the formation of a tricuspid terminus, somewhat reminiscent of the condition seen in Cotylorhynchus. However, the kind of bulging of the lingual side of the tooth below the crown seen in Cotylorhynchus, and geologically younger caseids is only modestly developed in Arisierpeton.[1]

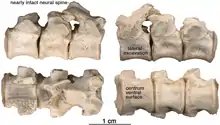

Vertebrae

The string of three posterior dorsal vertebrae GAA 00244, were found in the same pocket as the dentigerous elements, but their association with the holotype and other referred specimens is tentative. The vertebrae have the typical cylindrical, spool-shaped centra, with shallow lateral excavations, but the most striking feature of the centra is the presence of flat ventral surfaces between the rounded anterior and posterior articular surface. The centra are solidly fused to the neural arches, which carry well-developed, massive, transverse processes, short zygapophyseal surfaces, and slender, presumably anteroposteriorly short, simple neural spines. The transverse processes are short and stout, and were not fused to the ribs. The size of the transverse processes indicate that these are most likely posterior dorsal vertebrae. A pair of small excavations are present dorsally on the neural arch, between and slightly posterior to the prezygapophyses. There is no evidence of ventral excavation of the centra for intercentra, a common feature of caseid posterior dorsal vertebrae. Thus, the morphology of the centra and neural arches are entirely in agreement with known caseid morphology. They can be assigned with confidence to a small caseid. However, their assignment to Arisierpeton is tentative and based on co-occurrence and size, and there are no recognizable diagnostic features on the centra below the family level.[1]

References

- Riesz, Robert R. "A small caseid synapsid, Arisierpeton simplex gen. et sp. nov., from the early Permian of Oklahoma, with a discussion of synapsid diversity at the classic Richards Spur locality". PeerJ. 7: e6615. doi:10.7717/peerj.6615. PMC 646239. PMID 30997285. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License