Balance shaft

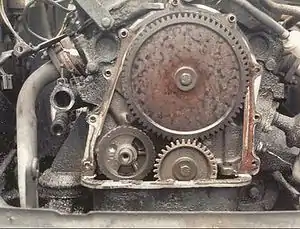

Balance shafts are used in piston engines to reduce vibration by cancelling out unbalanced dynamic forces. The balance shafts have eccentric weights and rotate in opposite direction to each other, which generates a net vertical force.

The balance shaft was invented and patented by British engineer Frederick W. Lanchester in 1904. It is most commonly used in inline-four and V6 engines used in automobiles and motorcycles.

Overview

_031.jpg.webp)

The operating principle of a balance shaft system is that two shafts carrying identical eccentric weights rotate in opposite directions at twice the engine speed. The phasing of the shafts is such that the centrifugal forces produced by the weights cancel the vertical second-order forces (at twice the engine RPM) produced by the engine.[1] The horizontal forces produced by the balance shafts are equal and opposite, and so cancel each other.

The balance shafts do not reduce the vibrations experienced by the crankshaft. [2]

Applications

Two-cylinder engines

Numerous motorcycle engines— particularly straight-twin engines— have employed balance shaft systems, for example the Yamaha TRX850 and Yamaha TDM850 engines have a 270° crankshaft with a balance shaft. An alternative approach, as used by the BMW GS parallel-twin, is to use a 'dummy' connecting rod which moves a hinged counterweight.

Four-cylinder engines

Balance shafts are often used in inline-four engines, to reduce the second-order vibration (a vertical force oscillating at twice the engine RPM) that is inherent in the design of a typical inline-four engine. This vibration is generated because the movement of the connecting rods in an even-firing inline-four engine is not symmetrical throughout the crankshaft rotation; thus during a given period of crankshaft rotation, the descending and ascending pistons are not always completely opposed in their acceleration, giving rise to a net vertical force twice in each revolution (which increases quadratically with RPM).[3]

The amount of vibration also increases with engine displacement, resulting in balance shafts often being used in inline-four engines with displacements of 2.2 L (134 cu in) or more. Both an increased stroke or bore cause an increased secondary vibration; a larger stroke increases the difference in acceleration and a larger bore increases the mass of the pistons.

The Lanchester design of balance shaft systems was refined with the Mitsubishi Astron 80, an inline-four car engine introduced in 1975. This engine was the first to locate one balance shaft higher than the other, to counteract the second order rolling couple (i.e. about the crankshaft axis) due to the torque exerted by the inertia caused by increases and decreases in engine speed.[4][5]

In a flat-four engine, the forces are cancelled out by the pistons moving in opposite directions. Therefore balance shafts are not needed in flat-four engines.

Five-cylinder engines

Balance shaft are also used in Straight-five engines such as GM Vortec 3700.

Six-cylinder engines

In a straight-six engine and flat-six engine, the rocking forces are naturally balanced out, therefore balance shafts are not required.

V6 engines are inherently unbalanced, regardless of the V-angle. Any inline engine with an odd number of cylinders has a primary imbalance, which causes an end-to-end rocking motion. As each cylinder bank in a V6 has three cylinders, each cylinder bank experiences this motion.[6] Balance shaft(s) are used on various V6 engines to reduce this rocking motion.

See also

References

- "Engine Balance and the Balance Shafts". www.zzperformance.com. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- "Weighing the Benefits of Engine Balancing". www.babcox.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2009. Retrieved 12 December 2004.

- "Shaking forces of twin engines", Vittore Cossalter, Dinamoto.it

- Carney, Dan (2014-06-10). "Before they were carmakers". UK: BBC. Retrieved 2018-11-01.

- Nadel, Brian (June 1989). "Balancing Act". Popular Science. p. 52.

- "The Physics of: Engine Cylinder-Bank Angles". www.caranddriver.com. 14 January 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2019.