Battle of Flint River

The Battle of Flint River was a failed attack by Spanish and Apalachee Indian forces against Creek Indians in October 1702 in what is now the state of Georgia. The battle was a major element in ongoing frontier hostilities between English traders from the Province of Carolina and Spanish Florida, and it was a prelude to more organized military actions of Queen Anne's War.

| Battle of Flint River | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Queen Anne's War | |||||||

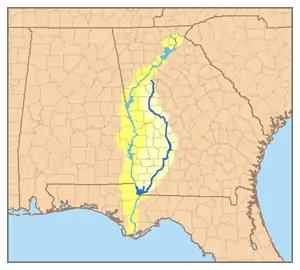

This detail of an early 18th-century map shows the approximate location of the battle on the Flint River. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Apalachee |

Creek Apalachicola | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Francisco Romo de Uriza | Anthony Dodsworth | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 800, mostly Indian | 400, mostly Indian | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| most killed or captured | unknown | ||||||

The Creeks, assisted by a small number of Englishmen led by trader Anthony Dodsworth, ambushed the invaders on the banks of the Flint River. More than half of the Spanish-Indian force was killed or captured. Both English and Spanish authorities reacted to the battle by accelerating preparations that culminated in the Siege of St. Augustine in November 1702.

Background

English and Spanish colonization efforts in southeastern North America began coming into conflict as early as the middle of the 17th century. The English founding of the Province of Carolina in 1663 and Charles Town (present-day Charleston, South Carolina) in 1670 significantly raised tensions with the Spanish who had long been established in Florida.[1] Traders and slavers from the new province penetrated into Spanish Florida, leading to raiding and reprisal expeditions on both sides.[2] In 1700, Carolina's governor, Joseph Blake, threatened the Spanish that English claims to Pensacola, established by the Spanish in 1698, would be enforced.[3] Carolina traders such as Anthony Dodsworth and Thomas Nairne had established alliances with Creek Indians in the upper watersheds of rivers draining into the Gulf of Mexico, who they supplied with arms and from whom they purchased slaves and animal pelts.[2]

The Spanish population of Florida at the time was fairly small. Since its founding in the 16th century, the Spanish had set up a network of missions whose primary purpose was to pacify the local Indian population and convert them to Roman Catholicism. In the Apalachee region (roughly present-day western Florida and southwestern Georgia) there were 14 mission communities with a total population in 1680 of about 8,000. Many, but not all, of these communities were populated by the Apalachee; others were from different tribes that had migrated southward to the area.[4] The Spanish had a policy of not arming these Indians with muskets, and the Apalachee missions suffered from English and Creek raids in 1701.[5]

In January 1702 Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, the French founder of Mobile, warned the Spanish commander at Pensacola that he should properly arm the Apalachees and engage in a vigorous defense against English incursions into Spanish territory. D'Iberville even offered equipment and supplies for the purpose.[6] Following the destruction by raiders of the Timucuan mission of Santa Fé de Toloca in May 1702, Spanish Florida's Governor Joseph de Zúñiga y Zérda authorized an expedition into the Creek territories.[5]

Battle

Zúñiga ordered Don Francisco Romo de Uriza, a Spanish captain, to San Luis de Apalachee, where he raised a force of about 800 Apalachee and Spanish from the surrounding mission communities.[5] Uriza's report has not been found, so a breakdown of his force is not presently known.[7] Word of this reached the Apalachicola community of Achita, where Carolina trader Anthony Dodsworth (referred to in Spanish documents as "Don Antonio") was meeting with the local tribes. According to a report an Indian woman made to Manuel Solano, the deputy governor at San Luis, about 400 warriors, principally Apalachicolas and Chiscas, went with Dodsworth, two other white men, and two blacks, to meet the Uriza's force. They left Achita on roughly October 7, the same day Uriza left Apalachee.[8] The exact date of the battle is unknown; the woman reporting to Solana saw the battlefield on October 18,[8] the day Uriza and the remnants of his force returned to the Apalachee town of Bacacua.[9]

Dodsworth assembled his force, which numbered about 500, with the blessing of the Apalachicola chief Emperor Brim.[10] The two forces met near the Flint River when the Apalachee made a predawn attack on the Apalachicola camp. Anticipating the possibility of this sort of attack, Dodsworth and the Apalachicolas had arranged their blankets to appear occupied and concealed themselves near the camp. When the Apalachee attacked the false camp, the Apalachicolas fell upon them.[11] With the superiority of their weapons, the British-supported Indians routed the Spanish force. Uriza was reported to have only 300 men when he returned to Apalachee.[9]

Aftermath

The defeat immediately put Zúñiga on the defensive. He ordered the fort at San Luis to be completed and adequate supplies for a siege laid in.[11] The battle further stirred up passions in Charles Town, where Governor James Moore had already secured approval for an expedition against St. Augustine after learning that war had formally been declared in Europe between England and Spain.[12] His expedition departed Charles Town in November and failed in its objective, although Spanish-Indian mission communities in Guale Province were destroyed in the process.[13] Moore, in 1704, led an expedition against the Apalachee missions that virtually wiped them out.[11] By the end of Queen Anne's War in 1713, the English had practically depopulated present-day Georgia of Spaniards and their allied Indian tribes, leaving the Spanish in control of little more than St. Augustine and Pensacola.[14]

Two widely separated highway markers have been erected in Georgia to commemorate the battle. The Georgia Historical Commission erected a highway marker in central Georgia at 31.960667°N 83.910967°W in Crisp County near Georgia Veterans State Park in 1965,[15] and the Historic Chattahoochee Commission, in 1985, placed a marker at 30.913148°N 84.5672°W in the southern Georgia town of Bainbridge.[16]

Notes

- Arnade (1962), p. 31

- Crane (1919), p. 381

- Crane (1919), p. 384

- Boyd et al, p. 10

- Crane (1956), p. 74

- Crane (1956), p. 73

- Boyd (1953), p. 471

- Boyd (1953), p. 469

- Boyd (1953), p. 470

- Pearson, p. 57

- Pearson, p. 58

- Crane (1919), p. 76

- Arnade (1959), pp. 14–15

- Arnade (1962), pp. 35–36

- "GeorgiaInfo: Spanish-Indian Battle Marker". Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- "Georgia Historical Society: Battle of 1702 Marker". Georgia Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

References

| Library resources about Battle of Flint River |

- Arnade, Charles W (1959). The Siege of St. Augustine 1702. University of Florida Monographs: Social Sciences #3. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press. OCLC 1447747.

- Arnade, Charles W (1962). "The English Invasion of Spanish Florida, 1700–1706". The Florida Historical Quarterly. Florida Historical Society. 41 (1): 29–37. JSTOR 30139893.

- Boyd, Mark F; Smith, Hale G; Griffin, John W (1999) [1951]. Here They Once Stood: the Tragic End of the Apalachee Missions. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-1725-9. OCLC 245840026.

- Boyd, Mark F (1953). "Further Consideration of the Apalachee Missions". The Americas. Academy of American Franciscan History. 9 (4): 459–480. JSTOR 978405.

- Crane, Verner W (1919). "The Southern Frontier in Queen Anne's War". The American Historical Review. 24 (3): 379–395. doi:10.1086/ahr/24.3.379. JSTOR 1835775.

- Crane, Verner W (1956) [1929]. The Southern Frontier, 1670–1732. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015051125113. OCLC 631544711.

- Pearson, Fred Lamar, Jr (1978). "Anglo-Spanish Rivalry in the Chattahoochee Basin and West Florida, 1685–1704". The South Carolina Historical Magazine. Vol. 79 no. 1. South Carolina Historical Society. pp. 50–59. JSTOR 27567478.

External links

- Battle of 1702 historical marker