Siege of Port Royal (1707)

The Siege of Port Royal in 1707 was two separate attempts by English colonists from New England to conquer Acadia (roughly the present-day Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) by capturing its capital Port Royal (now Annapolis Royal) during Queen Anne's War. Both attempts were made by colonial militia, and were led by men inexperienced in siege warfare. Led by Acadian Governor Daniel d'Auger de Subercase, the French troops at Port Royal easily withstood both attempts, assisted by irregular Acadians and the Wabanaki Confederacy outside the fort.

| Siege of Port Royal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Queen Anne's War | |||||||

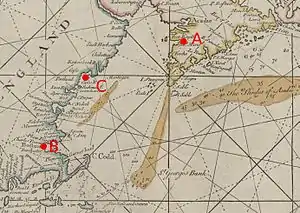

Annotated detail from a 1713 map showing eastern New England and southern Nova Scotia/Acadia. Port Royal is at A, Boston at B, and Casco Bay at C. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Mi'kmaq militia[1] | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

John March Francis Wainwright Captain Charles Stuckley, RN Winthrop Hilton Cyprian Southack[2] |

Daniel d'Auger de Subercase Bernard-Anselme d'Abbadie de Saint-Castin Pierre Morpain Pierre Maisonnat dit Baptiste Antoine Gaulin[3] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1,150 provincial soldiers (first siege)[4] 850 provincial soldiers (second siege)[5] |

160 troupes de la marine 60 Acadian militia 100 Wabanaki[6] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 16 killed; 16 wounded;[7] reports vary widely[8] | At least 5 killed; 20 wounded[9] reports vary widely[10] | ||||||

The first siege began on June 6, 1707, and lasted 11 days. The English colonel, John March, was able to establish positions near Port Royal's fort, but his engineer claimed the necessary cannons could not be landed, and the force withdrew amid disagreements in the war council. The second siege began August 22, and was never able to establish secure camps, owing to spirited defensive sorties organized by Acadian Governor Daniel d'Auger de Subercase.

The siege attempts were viewed as a debacle in Boston, and the expedition's leaders were jeered upon their return. Port Royal was captured in 1710 by a larger force that included British Army troops; that capture marked the end of French rule in peninsular Acadia.

Background

Port Royal (Habitation) was the capital of the French colony of Acadia until its destruction in 1613 by English raiders led by Samuel Argall.[11] A new Port Royal was established in the 1630s on the site the Scottish Charlesfort at what is today Annapolis Royal. The settlement was attacked several times by the English, including the 1690 capture by forces from the Province of Massachusetts Bay, although it was restored to France by the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick.[12] It fell for the last time to the British in 1710.

French preparations

With the outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1702, colonists on both sides again prepared for conflict. Acadia's governor, Jacques-François de Monbeton de Brouillan, had, in anticipation of war, already begun construction of a stone and earth fort in 1701, which was largely completed by 1704.[13] Following a French raid on Deerfield on the Massachusetts frontier in February 1704, the English in Boston organized a raid against Acadia the following May. Led by Benjamin Church, they raided Grand Pré and other Acadian communities.[14] English and French accounts differ on whether Church's expedition mounted an attack on Port Royal. Church's account indicates that they anchored in the harbour and considered making an attack, but ultimately decided against the idea; French accounts claim that a minor attack was made.[15]

When Daniel d'Auger de Subercase became governor of Acadia in 1706, he went on the offensive, encouraging Indian raids against English targets in New England. He also encouraged privateering from Port Royal against English colonial shipping. The privateers were highly effective; the English fishing fleet on the Grand Banks was reduced by 80 percent between 1702 and 1707, and some English coastal communities were raided.[16]

New England preparations

English merchants in Boston had long traded with Port Royal, and some of this activity had continued even after the war began.[17] Some of these merchants, notably Samuel Vetch, were closely associated with Massachusetts Bay's Governor Joseph Dudley, and by 1706 outrage began growing in the colonial assembly over the matter. Vetch chose to deal with these allegations by going to London to press a case for a military expedition against New France, while Dudley, who had previously requested such support without response, chose to demonstrate his anti-French sentiment by organizing an expedition against Port Royal using mostly colonial resources.[18] In March 1707 he revived an idea he had first developed in 1702 that called for provincial militia to man an expedition supported by resources of the Royal Navy that were locally available.[19] His proposal was approved by the assembly on 21 March. Colonial popular opinion was divided on the need for the expedition: some ministers argued in its favour from the pulpit, while Cotton Mather "Pray'd God not to carry his people hence."[20]

Massachusetts raised two full regiments, totalling nearly 1,000 men; New Hampshire provided 60 men, Rhode Island provided 80, and a company of Indians from Cape Cod was also recruited.[4][21] Recruiting was difficult in Massachusetts due to the lack of enthusiasm for the endeavour, and authorities were forced to draft men to fill the ranks.[22] Connecticut was also asked to contribute to the expedition, but declined, citing bad feeling over the return of Port Royal by treaty after its capture in 1690.[23] The force, which was placed under the command of Massachusetts Colonel John March, totalled 1,150 soldiers and 450 sailors, and was carried by a fleet of 24 ships, including the 50 gun man of war Deptford under the command of Captain Charles Stuckley, and the 24 gun colonial Province Galley of Cyprian Southack.[4][22] (March took a former prisoner of the Maliseet, John Gyles as his translator.)[24]

First siege

The English fleet arrived outside the channel of the Port Royal harbour on June 6, and troops were landed the next day. Governor Subercase's defence force at the time consisted of 100 troupes de la marine that had fortuitously been reinforced by the recent arrival of another 60 who were due to take command of a recently built frigate. Just hours before the English arrival he had also welcomed about 100 Abenaki Indians led by the young Bernard-Anselme d'Abbadie de Saint-Castin. As soon as the English ships were spotted, Subercase also called out the local militia, mustering about 60 men.[6]

Colonel March landed with about 700 men to the north of the fort, and another 300 to its south under the command of Colonel Samuel Appleton, with the goal of establishing a siege line around the fort.[6] Both forces were landed too far from the fort and spent the rest of the day marching toward it. Subercase sent a small force to the south on the morning of the 8th, who were driven back toward the fort by Appleton.[25] Subercase himself led a larger contingent to the north, where he established an ambush at a river March's force would have to cross. After a sharp battle in which Subercase's horse was shot out from under him, the defenders were pushed back into the fort.[26]

The New Englanders established camps about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from the fort. Subercase sent parties out of the fort to harass English foraging parties, giving rise to rumors that additional militia forces were en route from northern Acadia. The English managed to advance their lines closer to the fort, but their engineer, Colonel John Redknap, did not believe the expedition's heavy cannons could be landed safely, because they "must pass within command of the fort".[5] This led to disagreements between March, Redknap, and Stuckley which spelled the end of the expedition. After a final assault on June 16, which French accounts describe as a failed attempt to take the fort, and English accounts say was merely an attempt to destroy some buildings outside the fort, the expedition embarked on its ships and sailed off on the 17th. March directed the fleet to sail for Casco Bay (near present-day Portland, Maine).[27][28]

Interlude

From Casco Bay Colonel March sent a letter to Boston, in which he laid the blame for the expedition's failure on Stuckley and Redknap.[27] News of the failure preceded his messengers, and they were met upon their arrival by a jeering crowd of women and children.[29] Colonel Redknap, one of the messengers, was able to convince Governor Dudley that he had acted within his orders, and blame was generally attached to March for the failure.[30] Dudley issued orders to March that the fleet should stay put, with all men remaining aboard under penalty of death, while his council considered the next step. Dudley eventually sent reinforcements and a three-man commission (including two militia colonels and John Leverett, a lawyer with no military experience) to oversee affairs, and ordered the expedition to make a second attack.[29] Despite the orders, desertion from the fleet was high, and the force was reduced to about 850 when it sailed for Port Royal in late August. Colonel March resigned the expedition command and was replaced by Colonel Francis Wainwright.[29]

Governor Subercase was forewarned of the second attempt, and had erected additional defenses to impede the attackers' approaches.[29] He was also reinforced by the fortuitous arrival of the Intrepide, a French frigate under the command of Pierre Morpain.[31] His crew was added to the defences, and captured prize ships he brought with him provided needed provisions for the fort.[29]

Second siege

The English fleet arrived near Port Royal on August 21, and Wainwright landed his troops about 2 miles (3.2 km) below (south of) the fort the next day and marched them to a position about 1 mile (1.6 km) north of the fort.[29] This area, where March had previously camped, was one of the areas near which Subercase had thrown up additional defensive earthworks.[32] On August 23 Wainwright sent a detachment of 300 to clear a path for the heavy cannon; this attempt was repulsed by forces sent out by Subercase to harass them. Using guerrilla-style tactics and fire from the fort's cannons, they forced the English to retreat to their camp.[31] This defeat apparently had a significant effect on English morale; Wainwright wrote that his camp was "surrounded with enemies and judging it unsafe to proceed on any service without a company of at least one hundred men."[31] In what was probably the most serious clash, an English party cutting brush was ambushed by a French and Indian force, and nine of the party were killed. The situation got so bad in the English camp that on the 27th they withdrew to a camp protected by their ships' guns.[33] The camp was not properly fortified, and the Englishmen were constantly subjected to sniping and attacks from swarming French and Indians.[34] When Wainwright made a second landing at another point on August 31, Subercase himself led 120 soldiers out of the fort. About 70 men engaged the New Englanders in hand-to-hand combat, which was fought with axes and musket butts. Saint-Castin and almost 20 of his men were wounded while five others were killed.[9] The next day, September 1, the English reembarked on their ships, and sailed back to Boston.[34] The French in their reports claimed to have killed as many as 200 men, but English sources claim only about 16 killed and 16 wounded in the siege.[9][35]

Aftermath

The expedition's return to Boston was also met with jeers. Dudley's commissioners were sarcastically called "the three Port Royal worthies" and "the three champions".[36] Dudley's reports of the affair minimized its failings, pointing out that many plantations around Port Royal had been destroyed during the two sieges.[37] Dudley also refused to make inquiries into the expedition's failure, fearing the blame would be placed on him.[38]

Subercase, concerned that the British might return the following year, worked to strengthen the fortifications at Port Royal. He also built a small warship to assist in the colony's defenses, and convinced Morpain to raid New England shipping.[39] The privateer was so successful that by the end of 1708 Port Royal was overcrowded with prisoners from the captured prizes.[40]

None of this helped save Port Royal from the next attack, since France failed to send any significant support, while the British mobilized larger and better-organized forces. Samuel Vetch, with support from Dudley, Boston merchants, and the New England fishing community, successfully lobbied Queen Anne for military support for an expedition to conquer all of New France in 1709.[41][42] This prompted the colonists to mobilize in the expectation that troops would arrive from England; their efforts were aborted when the promised military support failed to materialize. Vetch and Francis Nicholson returned to England in its aftermath, and again secured promises of military support for an attempt on Port Royal in 1710.[43] In the summer of 1710, a fleet arrived in Boston carrying 400 marines.[44] Augmented by colonial regiments, this force captured Port Royal after a third siege in 1710.[45]

See also

Notes

- Penhallow, p.51

- http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~pattyrose/engel/gen/fg08/fg08_314.htm

- Lee, David (1979) [1969]. "Gaulin, Antoine". In Hayne, David (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. II (1701–1740) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Drake, p. 227

- Griffiths (2005), p. 216.

- Griffiths (2005), p. 215.

- Winthrop Hilton's Journal

- Griffiths (2005), pp. 216–217.

- Dunn, p. 74

- Griffiths (2005), pp. 216-217.

- MacVicar, pp. 13–29

- MacVicar, pp. 41–44

- Baudry, René (1979) [1969]. "Monbeton de Brouillan, Jacques-François de". In Hayne, David (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. II (1701–1740) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Drake, pp. 193–202

- Drake, p. 202

- Faragher, p. 113

- Peckham, p. 66

- Rawlyk, p. 100

- Rawlyk, pp. 93, 100

- Rawlyk, p. 101

- Peckham, p. 67

- Rawlyk, p. 102

- Kimball, p. 120

- MacNutt, W. S. (1974). "Gyles, John". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- MacVicar, p. 51

- MacVicar, p. 52

- MacVicar, p. 53

- Drake, p. 233

- MacVicar, p. 54

- Kimball, p. 122

- Griffiths (2005), p. 217.

- Drake, p. 234

- MacVicar, p. 55

- MacVicar, p. 56

- Drake, p. 235

- Drake, p. 236

- Kimball, p. 123

- Rawlyk, p. 106

- Pothier, Bernard (1974). "Morpain, Pierre". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- MacVicar, pp. 58–59

- MacVicar, p. 60

- Rawlyk, p. 116

- Drake, pp. 250–256

- Rawlyk, p. 118

- MacVicar, pp. 62–64

References

- Drake, Samuel Adams (1910) [1897]. The Border Wars of New England. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. OCLC 2358736.

- Dunn, Brenda (2004). A History of Port-Royal/Annapolis Royal 1605–1800. Halifax, NS: Nimbus. ISBN 978-1-55109-484-7. OCLC 54775638.

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05135-3. OCLC 217980421.

- Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. Norman, Oklahoma: Oklahoma University Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3. OCLC 159919395.

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.

- Kimball, Everett (1911). The Public Life of Joseph Dudley. New York: Longmans, Green and Co. OCLC 1876620.

- MacVicar, William (1897). A Short History of Annapolis Royal: the Port Royal of the French, From its Settlement in 1604 to the Withdrawal of the British Troops in 1854. Toronto: Copp, Clark. OCLC 6408962.

- Peckham, Howard (1964). The Colonial Wars, 1689–1762. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 1175484.

- Plank, Geoffrey (2001). An Unsettled Conquest. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1869-5. OCLC 424128960.

- Rawlyk, George (1973). Nova Scotia's Massachusetts. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-0142-3. OCLC 1371993.

- Reid, John; Basque, Maurice; Mancke, Elizabeth; Moody, Barry; Plank, Geoffrey; Wicken, William (2004). The 'Conquest' of Acadia, 1710: Imperial, Colonial, and Aboriginal Constructions. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-3755-8. OCLC 249082697.