Capture of Martinpuich

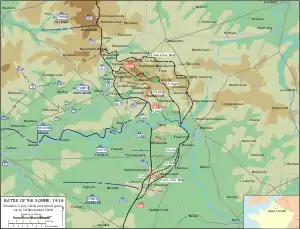

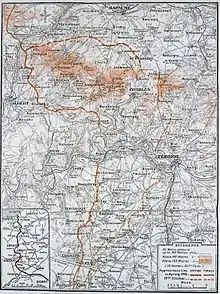

The Capture of Martinpuich took place on 15 September 1916. Martinpuich is situated 18 miles (29 km) south of Arras, near the junction of the D 929 and D 6 roads, opposite Courcelette, in the Pas-de-Calais, France. The village lies south of Le Sars, west of Flers and north-west of High Wood. In September 1914, during the Race to the Sea, the divisions of the German XIV Corps advanced on the north bank of the Somme westwards towards Albert and Amiens, passing through Martinpuich. The village became a backwater until 1916, when the British and French began the Battle of the Somme (1 July – 13 November) and was the site of several air operations by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), which attacked German supply dumps in the vicinity.

| Capture of Martinpuich | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Somme, First World War | |||||||

Battle of the Somme 1 July – 18 November 1916 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Douglas Haig |

Erich Falkenhayn Crown Prince Rupprecht | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1 division | 1 regiment | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,854 | c. 700 prisoners | ||||||

Martinpuich | |||||||

The 15th (Scottish) Division of the Fourth Army captured the village on 15 September, during the Battle of Flers–Courcelette (15–22 September). Several hundred prisoners of the 3rd Bavarian Division and the 45th Reserve Division were taken and after the village was captured, the pre-war light railway was repaired. The village was lost on 25 March 1918, during the German spring offensive (Operation Michael) and was recaptured for the last time on 25 August, by the British 21st Division.

Background

1914–1915

Troops of the 4th Bavarian Division reached Martinpuich on 27 September, during the Battle of Albert (25–29 September 1914) and the 28th (Baden) Reserve Division advanced on the south side of the Bapaume–Albert road, through the village towards Fricourt on 28 September.[1] Operations on the Somme south of the Ancre diminished in 1915, with only trench raids and night patrols undertaken. A tacit understanding developed that if the Germans bombarded Aveluy and Mesnil, Martinpuich and Courcelette were bombarded in retaliation.[2]

1916

On 25 July, a German machine-gun detachment saw an RFC aircraft flying low from Martinpuich, shot it down and collected a prize of ℳ 350. During the Battle of Pozières (23 July – 3 September) Martinpuich became a transit point for German reinforcements moving to the front and for the evacuation of wounded.[3] On 30 July, a raid on the village by 23 Squadron Royal Flying Corps (RFC) caused a huge explosion, which sent clouds of smoke high into the air and caused a blaze which was still burning when the squadron raided the village late the next morning.[4]

Prelude

British offensive preparations

German positions in the neighbourhood of Martinpuich were systematically bombarded by the guns of III Corps, results being reviewed by the examination of photographs taken by reconnaissance aircrews. The field batteries concentrated on wire cutting, which was observed by ground and air observers and German artillery, directed by observers in High Wood retaliated with great accuracy.[5] Working parties of the 15th (Scottish) Division managed to dig four jumping off trenches beyond the front line, called Egg, Bacon, Ham and Liver. Dumps of bombs and ammunition were accumulated, dressing stations were built and water supplies established.[6]

To hold the line while the 45th Brigade and 46th Brigade were practising the attack, the 44th Brigade of the 15th (Scottish) Division, the 103rd Brigade of the 34th Division and its pioneer battalion, the 18th Northumberland Fusiliers, took over the line on 7 September. Next day, two companies of the 9th Black Watch attacked from Bethell Sap to a German trench running from the north-west of High Wood, during an attack on the wood by the 1st Division, took thirty prisoners from Bavarian Infantry Regiment 18 and defeated a powerful German counter-attack. After the 1st Division was repulsed the party withdrew, having lost 98 casualties. The 45th and 46th brigades spent eight days rehearsing the attack on ground marked to resemble the terrain south of Martinpuich. Three days before the attack, two battalions of the 23rd Division were attached to the 15th (Scottish) Division as reinforcements. During the night of 14/15 September, the attacking battalions made their way to Egg, Bacon, Ham and Liver trenches.[7]

British plan of attack

For the Fourth Army attack, the first objective (green line) was set 600 yd (550 m) forward at the Switch Line and the connecting lines which covered Martinpuich. The second objective (brown line) was 500–800 yd (460–730 m) further on in the 15th (Scottish) Division area, among more defences between Martinpuich and Flers. The final objective (blue line) was another 350 yd (320 m) on for the 15th (Scottish) Division, which would envelop the village, outflank German artillery positions around Le Sars and gain touch with the right flank of the Reserve Army. III Corps had the field artillery of the 15th, 23rd, 47th, 50th and 55th divisions, with two hundred and twenty-eight 18-pounder field guns and sixty-four 4.5-inch howitzers, distributed around Mametz Wood, Caterpillar and Sausage valleys, in the vicinity of La Boisselle.[lower-alpha 1] Eight tanks were allotted to III Corps; two nights before the attack, the tanks were to move to corps assembly areas 1–2 miles (1.6–3.2 km) from the front line, move up to the departure points in the front line the next night, while the assembly was disguised by aircraft flying overhead and the tanks navigated by the light of the full moon.[8]

The 45th Brigade was to attack on the right with two battalions, two in support and a battalion of the 23rd Division in reserve. The 46th Brigade on the left was to attack with three battalions, one in support and in reserve, another attached battalion of the 23rd Division. A section of an engineer field company was to accompany each brigade. The 44th Brigade was to be held in reserve and four tanks of D Company, Heavy Section, Machine Gun Corps were to assist the infantry. To maintain secrecy, aircraft were arranged to fly over the German lines again, to drown the sound of the tank engines as they moved into position. Artillery support was planned by Brigadier-General Fasson, the divisional CRA, who had the divisional artillery and brigades of the 1st and 23rd divisional artilleries for a creeping barrage moving at 50 yd (46 m) per minute, except for a tank lane 100 yd (91 m) wide, to avoid hitting the tanks as they advanced. A preparatory bombardment was to begin on 12 September but no hurricane bombardment was to be fired at zero hour (6:20 a.m.), the tanks and the creeping barrage being relied on to keep the Germans under cover. Three objectives had been set, with the last one along the southern fringe of Martinpuich but a late amendment on 14 September, required the leading battalions to probe forwards three hours after zero, if the initial attack succeeded.[9]

German defensive preparations

In late June 1916, as the British preparatory bombardment for the Battle of the Somme fell on the north bank of the Somme, German regimental headquarters in villages were made uninhabitable and French civilians in Martinpuich and other villages were moved away. On 26 and 27 June, a British chlorine gas discharge passed over the rearward villages and reached as far as Bapaume.[10] In September 1916, Martinpuich was held by Bavarian Infantry Regiment 17 BIR 17) of the 3rd Bavarian Division. West and south of the village lay Hook Trench the Tangles trenches and Bottom Trench. Running west from the village was Factory Lane.[11] In early September, Rupprecht found that frequent relief of troops opposite the British were essential and stripped fresh divisions and other units from the other armies of his army group. Rupprecht moved the 85th Reserve Brigade and the 45th Reserve Division from the 4th Army in Flanders, into the area between Thiepval and Martinpuich. After General Erich von Falkenhayn was superseded as the Chief of the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, the German General Staff) on 29 August, Generals Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff visited the Western Front and ordered an end to offensive operations at the Battle of Verdun and the reinforcement of the Somme front. Tactics were reviewed and a more "elastic" defence was advocated, to replace the defence of tactically unimportant ground and routine counter-attack of break-ins of German positions.[12]

Battle

15 September

| Day | Rain mm |

Max–Min Temp (°F) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 7th | 0.0 | 70°–54° | fine |

| 8th | 0.0 | 70°–55° | fine dull |

| 9th | 5 | 75°–57° | rain |

| 10th | 1 | 68°–57° | dull |

| 11th | 0.1 | 66°–54° | dull |

| 12th | 0.0 | 72°–55° | fine |

| 13th | 0.0 | 72°–52° | dull |

| 14th | 0.0 | 61°–41° | wind |

| 15th | 0.0 | 59°–43° | haze |

| 16th | 0.0 | 66°–41° | sun |

At 6:20 a.m. the 45th Brigade on the right made a rapid advance through The Cutting, Tangle South Trench and Tangle Trench, which fell easily and took several prisoners; the final objective was reached just after 7:00 a.m.[7] The front of the II Bavarian Corps disappeared in black smoke and a staff officer of Reserve Infantry Regiment 231 (RIR 231) received reports from Bavarian Infantry Regiment 17 (BIR 17), that the British had broken through in the mist and later that they were advancing through Martinpuich in large groups, before the telephone line was cut.[14] The 46th Brigade on the left could not attack parallel to the objective, due to the angle of the creeping barrage, the first objective at the sunken road being about 45° from the start line. (The unusual plan for the creeping barrage was necessary to maintain its synchronisation with the barrage on the 2nd Canadian Division front, which had a slower-moving barrage.)[7] The left-hand battalion had to veer left from the start and the centre battalion advanced 500 yd (460 m), then two companies half-turned left and the right two companies headed straight on to the objective. The centre battalion also had to capture Bottom Trench en route, while the right-hand battalion took part of Bottom Trench and Tangle Trench.[15]

Observers of 34 Squadron watched the attack and by 9:30 a.m., reported that the Scottish were on the southern edge of the village.[16] BIR 17 managed to establish a weak defence along the Sunken Road and the southern edge of Martinpuich and isolated parties fought on but the defence collapsed as soon as the Scottish troops pressed on to the second objective.[17] The first objective had been secured at 6:45 a.m. and the advance to the final objective began. Few casualties had been incurred but the number increased when some parties overran the creeping barrage, which was moving at 50 yd (46 m) per minute and German artillery and machine-gun fire increased. The defenders appeared to have been surprised and many prisoners were taken, particularly on the 46th Brigade front. The new line ran from the junction with the 50th Division at Tangle South, along Tangle Trench, then the southern fringe of Martinpuich to the Factory Line, where touch was gained with the 2nd Canadian Division[15]

After receiving reconnaissance reports that the south end of the village was empty, McCracken ordered the attacking brigades forward at noon to occupy Martinpuich and establish posts to the north, westwards of the Martinpuich–Eaucourt l'Abbaye road and down Push Alley to connect with the 2nd Canadian Division. The advance began at 3:00 p.m. and on the right, the 45th Brigade support battalion moved up on the right flank of the brigade, opposite and parallel to the objective, pushed through the north-east of the village to a hill and after a bombing fight, forced 189 survivors to surrender. A line of strong points were dug, from Gun Pit Trench eastwards around the village to Prue Trench, then to the boundary with the 50th Division on the right. Prue Trench was vacant, because the 50th Division troops had retired from the trench due to German artillery fire, leaving the 45th Brigade flank uncovered except by a machine-gun post, until the 50th Division reoccupied the trench later in the day. On the left flank, the 46th Brigade advance to Push Alley was barely opposed. During the night, German stores captured in the village were used to consolidate the captured ground; a trench was dug to connect the new line north of the village with Prue Trench and barbed wire found in the village was laid in front of the new defences.[18] Several battalions of the 50th Reserve Division counter-attacked at 5:30 p.m., between High Wood and Martinpuich but no attempt was made on the village.[19]

16 September

Two small counter-attacks were made by German troops in the early hours of 16 September and repulsed. An artillery officer visiting the front line, reported that German trenches were unoccupied. Patrols from two battalions went forward to investigate and returned having suffered many losses, the trenches having been full of troops; it was alleged that the gunner officer had misread his map. Later on, the 46th Brigade pushed the left flank up to the Albert–Bapaume road and in the afternoon, began to dig a line of advanced posts about 200 yd (180 m) in front of the new position.[20]

Aftermath

Analysis

In 1926, J. Stewart and John Buchan, the 15th Division historians, called the attack on Martinpuich a well planned and executed operation, in which infantry, artillery and engineers had worked together and inflicted a serious blow on the defenders, for relatively few casualties. An officer of BIR 17 wrote that the defensive barrage had been "a complete failure" and that close co-operation of the opposing infantry and artillery, was a result of the "remarkable achievements of their aviators", who watched the progress of the attack. Artillery observers had advanced with the infantry and established posts with telephones in a few hours.[21] A huge amount of engineer stores were found in the village and 13 machine-guns, three heavy howitzers, thee field guns and a trench mortar were captured.[22]

One of the two tanks which operated on the 15th Division front reached Bottom Trench, engaged German troops there and at Tangle Trench, then engaged machine-gunners in the village, before returning to refuel, after which it hauled small-arms ammunition forward; the second tank was knocked out before it reached the departure point. A tank allotted to the 50th Division on the right, knocked out three machine-guns on the east side of Martinpuich.[23] From 16–17 September, the division consolidated, digging communication trenches from the old front line, building bomb and ammunition stores and worked on dug outs; on 18 September, the 23rd Division began to relieve the 15th Division.[22] As Bavarian prisoners saw the accumulation of material behind the British front, they doubted that Germany could prevail against the plenty of the Allies but also felt sure that with similar resources, they would have been able to persist with the offensive and win the war.[24]

Casualties

The 15th Division had 1,854 casualties from 15–16 September and about 600–700 German prisoners were taken from RIR 133 of the 24th Reserve Division, RIR 111, BIR 17, 18 and 23 of the 3rd Bavarian Division, plus several artillerymen and machine-gunners of the 45th Reserve Division.[22][25]

Subsequent operations

An advanced dressing station was built in the village and late in 1916, a light Decauville railway was repaired and sidings installed, to run from Peake Woods near La Boisselle to the village. A regular service was started by petrol locomotive up Gun Pit Road and a walkway was built alongside.[26] On 2 November, Crown Prince Rupprecht the German army group commander on the Somme, wrote in his diary that the British were digging in west of Delville Wood to Martinpuich and Courcelette, which suggested that winter quarters were being built and that only minor operations were contemplated. Infantry attacks diminished but British artillery fire was constant, against which the large number of German guns in the area could only make a limited reply, due to a chronic shortage of ammunition. German counter-attacks were cancelled because of troop shortages.[27] Martinpuich was lost on 25 March 1918 during Operation Michael, the German spring offensive.[28] The village was recaptured for the last time by the 17th (Northern) Division on 25 August, during the Second Battle of Bapaume.[29]

Notes

- Five heavy and siege artillery groups had twenty-eight 6-inch howitzer, sixteen 8-inch howitzer, twelve 9.2-inch howitzer, one 15-inch howitzer, eight 4.7-inch guns, forty 60-pounder gun, ten 6-inch gun, one 9.2-inch gun and a 12-inch gun in Sausage Valley and around Fricourt.[8]

Footnotes

- Sheldon 2006, pp. 26, 28.

- Sheldon 2006, p. 85.

- Sheldon 2006, pp. 218, 234.

- Jones 2002, p. 257.

- Miles1992, pp. 297–298.

- Stewart & Buchan 2003, pp. 86–87.

- Stewart & Buchan 2003, p. 89.

- Miles1992, pp. 289, 293, 296.

- Stewart & Buchan 2003, pp. 88–89.

- Duffy 2007, p. 125.

- Gliddon 1987, p. 312.

- Miles1992, pp. 423–424.

- Gliddon 1987, pp. 419–421.

- Sheldon 2006, p. 290.

- Stewart & Buchan 2003, pp. 89–90.

- Jones 2002, p. 273.

- Sheldon 2006, p. 292.

- Stewart & Buchan 2003, pp. 91–92.

- Rogers 2010, p. 122.

- Stewart & Buchan 2003, pp. 92–93.

- Duffy 2007, p. 233.

- Stewart & Buchan 2003, p. 93.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 105–107.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 122–123.

- Miles1992, p. 337.

- Gliddon 1987, p. 313.

- Sheldon 2006, p. 371.

- Edmonds, Davies & Maxwell-Hyslop 1995, p. 479.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 268–269.

References

Books

- Duffy, C. (2007) [2006]. Through German Eyes: The British and the Somme 1916 (Phoenix ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2202-9.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Davies, H. R.; Maxwell-Hyslop, R. G. B. (1995) [1935]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-219-7.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1947]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: 8th August – 26th September The Franco-British Offensive. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. IV (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-191-6.

- Gliddon, G. (1987). When the Barrage Lifts: A Topographical History and Commentary on the Battle of the Somme 1916. Norwich: Gliddon Books. ISBN 978-0-947893-02-6.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. II (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-413-0. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- McCarthy, C. (1995) [1993]. The Somme: The Day-by-Day Account (Arms & Armour Press ed.). London: Weidenfeld Military. ISBN 978-1-85409-330-1.

- Miles, W. (1992) [1938]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916, 2nd July 1916 to the End of the Battles of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-901627-76-6.

- Rogers, D., ed. (2010). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-906033-76-7.

- Sheldon, J. (2006) [2005]. The German Army on the Somme 1914–1916 (Pen & Sword Military ed.). London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-1-84415-269-8.

- Stewart, J.; Buchan, J. (2003) [1926]. The Fifteenth (Scottish) Division 1914–1919 (Naval & Military Press ed.). Edinburgh: Wm. Blackwood and Sons. ISBN 978-1-84342-639-4.

Further reading

- Browne, D. G. (1920). The Tank in Action. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. OCLC 699081445.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-185-7.

- Fuller, J. F. C. (1920). Tanks in the Great War, 1914–1918. New York: E. P. Dutton. OCLC 559096645.

- Haigh, R. (1918). Life in a Tank. New York: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1906675.

- Philpott, W. (2009). Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme and the making of the Twentieth Century (1st ed.). London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0108-9.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (2005). The Somme. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10694-7.

- Watson, W. H. L. (1920). A Company of Tanks. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. OCLC 262463695.

- Williams-Ellis, A.; Williams-Ellis, C. (1919). The Tank Corps. New York: G. H. Doran. OCLC 317257337.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Capture of Martinpuich. |