Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt

Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt was a German front-line fortification, west of the village of Beaumont Hamel on the Somme. The redoubt was built after the end of the Battle of Albert (25–29 September 1914), and as French and later British attacks on the Western Front became more formidable, the Germans added fortifications and trench positions near the original lines around Hawthorn Ridge. At 7:20 a.m. on 1 July 1916, the British fired a huge mine beneath the Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt. Sprung ten minutes before zero hour, it was one of 19 mines detonated on the first day of the Battle of the Somme; the detonation of this mine was filmed by Geoffrey Malins. The attack on the redoubt by part of the 29th Division of VIII Corps (Lieutenant-General Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston) was a costly failure.

| Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Somme, in the First World War | |||||||

Trench Map showing Hawthorn ridge and crater at top left | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Hawthorn Ridge | |||||||

Hunter-Weston had ordered the mine to be fired early to protect the advancing infantry from falling debris but this also gave the Germans time to occupy the rear lip of the mine crater. When British parties advanced across no man's land to occupy the crater, they were engaged by German small-arms fire. A few British soldiers reached the objective but at noon they were ejected by a German counter-attack. The success of the German defence of the Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt crater contributed to the failure of the British attack on the rest of the VIII Corps front.

The British reopened the tunnel beneath the Hawthorn Ridge crater three days later and reloaded the mine with explosives for the Battle of the Ancre (13–18 November). The new mine was fired on 13 November in support of an attack on Beaumont-Hamel by the 51st (Highland) Division of V Corps. The Scottish infantry advanced from a trench 250 yd (230 m) from the German lines, half the distance of 1 July, with the support of tanks, an accurate creeping barrage and an overhead machine-gun barrage. Beaumont-Hamel was captured and 2,000 German prisoners taken.

Background

1914–1915

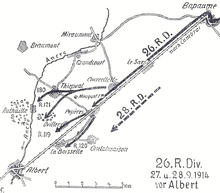

The 26th (Württemberg) Reserve Division (Generalmajor Franz von Soden) of the XIV Reserve Corps, arrived on the Somme in late September 1914, attempting to advance westwards towards Amiens. By 7 October, the advance had ended and temporary scrapes had been occupied. Fighting in the area from the Somme north to the Ancre, subsided into minor line-straightening attacks by both sides.[1][2] Underground warfare began on the Somme front, which continued when the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) took over from the French Second Army at the end of July 1915.[3] Miners brought from Germany late in 1914 tunnelled under Beaumont-Hamel and the vicinity to excavate shelters in which infantry companies could shelter and against which even heavy artillery could cause little damage.[4]

On the Somme front, a construction plan of January 1915, by which Falkenhayn intended to provide the western armies with a means to economise on infantry, had been completed. Barbed-wire obstacles had been enlarged from one belt 5–10 yd (4.6–9.1 m) wide to two belts 30 yd (27 m) wide and about 15 yd (14 m) apart. The front line had been increased from one trench to three, 150–200 yd (140–180 m) apart, the first trench (Kampfgraben) to be occupied by sentry groups, the second (Wohngraben) to accommodate the front-trench garrison and the third trench for local reserves. The trenches were traversed and had sentry-posts in concrete recesses built into the parapet. Dugouts had been deepened from 6–9 ft (1.8–2.7 m) to 20–30 ft (6.1–9.1 m), 50 yd (46 m) apart and large enough for 25 men. An intermediate line of strong points (the Stützpunktlinie) about 1,000 yd (910 m) behind the front line had also been built. Communication trenches ran back to the reserve line, renamed the second line, which was as well built and wired as the first line. The second line was built beyond the range of Allied field artillery, to force an attacker to stop and move field artillery forward before assaulting the line.[5]

1915–1916

On New Year's Eve 1915, a small mine was sprung under Redan Ridge north of Beaumont-Hamel, followed by German mine explosions on 2, 8 and 9 January. British mines were blown on 16, 17 and 18 January 1916 and both sides sprung mines in February; the Germans then dug a defensive gallery parallel to the front line to prevent surprises.[6] On the night of 6/7 April a German raid by II Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 119 (RIR 119) took place near Y Ravine, against the 2nd South Wales Borderers of the 29th Division and caused 112 casualties, for a loss of three killed and one man wounded. A big raid by the British on 30 April was seen by alert defenders and repulsed by small-arms fire and artillery as soon as it began. A report by the local German commander, showed that the preparations for the raid had been noticed a week before the attempt.[7]

After the Second Battle of Champagne in 1915, construction of a third line another 3,000 yd (2,700 m) back from the Stützpunktlinie had been begun in February 1916 and was nearly complete on the Somme front by 1 July.[5] Divisional sectors north of the Albert–Bapaume road were about 3.75 mi (6.04 km) wide.[8] German artillery was organised in a series of Sperrfeuerstreifen (barrage sectors). A telephone system was built with lines buried 6 ft (1.8 m) deep, for 5 mi (8.0 km) behind the front line, to connect the front line to the artillery. The Somme defences had two inherent weaknesses which the rebuilding had not remedied: The first was that the front trenches were on a forward slope, lined by white chalk from the subsoil and easily seen by ground observers. The second was that the defences were crowded towards the front trench, with a regiment having two battalions near the front-trench system and the reserve battalion divided between the Stützpunktlinie and the second line, all within 2,200 yd (1.3 mi; 2.0 km) of the front line, accommodated in the new deep dugouts.[9]

Prelude

German defensive preparations

The headwaters of the Ancre river flow west to Hamel through the Ancre valley, past Miraumont, Grandcourt, Beaucourt and St. Pierre Divion. On the north bank, pointing south-east, lie the Auchonvillers spur, with a lower area known as Hawthorn Ridge, Beaucourt spur descending from Colincamps and Grandcourt spur crowned with the village of Serre. Shallow valleys link the spurs, the village of Beaumont-Hamel lies in the valley between Auchonvillers and Beaucourt spurs. A branch in the valley known as Y Ravine lies on the side of Hawthorn Ridge. In 1916, the front of VIII Corps lay opposite the line from Beaucourt to Serre, facing the series of ridges and valleys, beyond the German positions to the east. The German front line ran along the eastern slope of Auchonvillers spur, round the west end of Y Ravine to Hawthorn Ridge, across the valley of Beaumont-Hamel to the part of Beaucourt spur known as Redan Ridge, to the top of the Beaucourt valley to Serre. An intermediate line known to the British as Munich Trench began at Beaucourt Redoubt and ran north to Serre. The second position ran from Grandcourt to Puisieux and the third position was 3 mi (4.8 km) further back.[10]

.png.webp)

No man's land was about 500 yd (460 m) wide from the Ancre northwards and narrowed to about 200 yd (180 m) beyond the redoubt on Hawthorn Ridge. The ground was flat and unobstructed, except for a sunken road from the Auchonvillers–Beaumont-Hamel road and a low bank near the German front trench. The German front had several shallow salients, flanks, a bastion at the west end of Y Ravine and cover in the valleys to the east. Beaumont-Hamel commanded the valley, which the VIII Corps divisions were to cross and had been fortified. Beaucourt Ridge further back, gave a commanding view to German artillery observers, who could see the gun flashes of British field artillery, despite the guns being dug in. British observers could not see beyond the German support trenches and the convex slope on the British side of no man's land, made it difficult for heavy artillery to hit the front position, parts of which was untouched by the preliminary bombardment.[10]

As signs of an Allied offensive increased during 1916, the lessons of the Second Battle of Artois and the Battle of Hébuterne in 1915, were incorporated into the defences of the Somme front.[11][lower-alpha 1] Observation posts were built in each defence sector, more barbed wire was laid and more Moritz telephone interception stations were installed, at the same time that more emphasis was laid on German telephone security. In early March and from 15–19 May, the chief engineer of the 2nd Army inspected the first position in the area of the 26th Reserve Division; only in the area of RIR 119 at Beaumont-Hamel and the trenches to the west around Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt, were there enough shell-proof concrete posts. German infantry made a great effort to gather intelligence, patrol and raid the British lines to snatch prisoners; the British became more experienced in responding to local attacks and began to use the same tactics. In May, Soden wrote that at least 10,000 rounds of artillery ammunition were necessary, to ensure the success of a raid. On the night of 10/11 June, a raiding party of RIR 119 failed to get forward, when the German artillery fired short.[12]

British offensive preparations

_mine%252C_Beaumont-Hamel.jpg.webp)

Special arrangements were made by the 29th Division to capture Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt. Three tunnels were dug under no man's land by tunnellers of the Royal Engineers. The first tunnel was to be a communication link to the Sunken Lane (shown in the film The Battle of the Somme, released in August 1916). British units had just moved into the Sunken Lane and the tunnel constructed by 252nd Tunnelling Company served to link it with the old British front line. In the early hours of 1 July, the 1st Battalion, The Lancashire Fusiliers were to use it to reach the Sunken Lane, ready to attack Beaumont-Hamel. Two other tunnels, First Avenue and Mary, named after the communications trenches leading into them, were Russian saps dug to within 30 yd (27 m) of the German front line, ready to be opened at 2:00 a.m. on 1 July, as emplacements for batteries of Stokes mortars.[13][14]

The 252nd Tunnelling Company placed mine H3 north of First Avenue and Mary, beneath the German stronghold on the ridge. The miners had dug a gallery for about 1,000 yd (910 m) from the British lines about 57 ft (17 m) underground beneath Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt on the crest of the ridge and charged it with 40,000 lb (18 long tons; 18,000 kg) of Ammonal. The VIII Corps commander, Lieutenant-General Aylmer Hunter-Weston, wanted the mine to be sprung four hours before the offensive began, so that the crater could be captured and consolidated in time for the alarm on the German side to have died down.[lower-alpha 2] On 15 June, the Fourth Army headquarters, ruled that all the mines on 1 July should be blown no later than eight minutes before zero; an unsatisfactory compromise was reached with Hunter-Weston to detonate the Hawthorn Redoubt mine ten minutes before zero hour.[16]

An earlier detonation of the H3 mine in the VIII Corps sector was expected to divert German attention to the north bank of the Ancre, which would help the attacks of X Corps and XV Corps further south, where success was more important. Opinion in the 29th Division was that time was needed for the débris from the great mine to fall to earth, although it was demonstrated that all but dust had returned to the ground within twenty seconds. Firing the mine early conformed to the plan to occupy the crater quickly but it required the heavy artillery bombardment of the redoubt and adjacent trenches to lift during the assault. All of the VIII Corps heavy artillery was ordered to lift at 7:20 a.m. and the field artillery to lift at 7:25 a.m. A light shrapnel barrage fired by the divisional field artillery was to continue on the front trench until zero hour; in the 29th Division sector, half of the guns were to lift three minutes early.[17]

British plan of attack

The 29th and 4th divisions were to advance east across the valley of Beaumont-Hamel to an intermediate line on Beaucourt spur and then advance to the second position in 3 1⁄2 hours. British artillery fire would lift off the German front trench at zero hour and the field artillery was to move eastwards in six lifts, from the first objective 15–20 minutes after zero and then lift in succession after about twenty minutes on each of the further objectives, the heavy artillery lifting five minutes earlier each time. The divisional field artillery was to lift for 100 yd (91 m) as each infantry advance began and then move east at 50 yd (46 m) per minute. Each division was to reserve two 18-pounder batteries ready to advance at short notice; visual signalling, runners, flares, signals to contact patrol aircraft, wide-angle signalling lamps were provided. Bombers (hand-grenade specialists in the infantry) carried flags to mark the front line.[18]

Battle

1 July

_1.jpg.webp)

A witness to the detonation of the Hawthorn Ridge mine was British cinematographer Geoffrey Malins, who filmed the 29th Division attack. Malins set up on the side of the White City trenches, about 0.5 mi (0.80 km) from Hawthorn Ridge, ready for the explosion at 7:20 a.m.,

The ground where I stood gave a mighty convulsion. It rocked and swayed. I gripped hold of my tripod to steady myself. Then for all the world like a gigantic sponge, the earth rose high in the air to the height of hundreds of feet. Higher and higher it rose, and with a horrible grinding roar the earth settles back upon itself, leaving in its place a mountain of smoke.

— Geoffrey Malins[19]

As soon as the mine blew, the bombardment on the German front line by heavy artillery lifted and Stokes mortars, which had been placed in advanced sites, along with four more in the sunken lane in no man's land, began a hurricane bombardment on the front trench. The regimental history of RIR 119 recorded that

... there was a terrific explosion which for the moment completely drowned out the thunder of the artillery. A great cloud of smoke rose up from the trenches of No 9 Company, followed by a tremendous shower of stones.... The ground all round was white with the debris of chalk, as if it had been snowing and a gigantic crater, over fifty yards in diameter and some sixty feet deep gaped like an open wound in the side of the hill.

— RIR 119 historian[20]

_2.jpg.webp)

and that the detonation was the signal for the German infantry to stand to at the shelter entrances. Two platoons of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (86th Brigade, 29th Division) with four machine-guns and four Stokes mortars, rushed the crater. As the British troops reached the near lip, they were engaged by small arms fire from the far lip and the flanks. At least three Gruppen of the 1st Platoon (Leutnant Renz) and the members of the 2nd Platoon (Leutnant Böhm) on the left side of the platoon area had been killed in the mine explosion. The entrances to the 3rd Platoon (Leutnant Breitmeyer) and some of the 2nd Platoon Unterstände (underground shelters) caved in and only two Gruppen escaped. The rest of the 9th Company in a Stollen (deep-mined dug-outs) survived but the entrances were blocked and the troops inside were not rescued until after the British attack.[21][22]

The detonation was swiftly followed by a German counter-barrage and in the next few minutes, German machine-guns opened fire all along the front. The British divisions forming up in no man's land to reach the jumping-off position 100 yd (91 m) short of the German front line, were caught in the machine-gun fire and suffered many casualties. German troops occupied the far lip of the crater at the Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt, turned machine-guns and trench mortars to the right and left flanks and fired into the British troops as they tried to advance. The attack on the redoubt and the rest of the VIII Corps front collapsed and was a costly failure. By 8:30 a.m., the only ground held by the 29th Division was the western lip of the crater. Two German platoons bombed from shell-hole to shell-hole towards the crater, forcing the survivors to retire to the British front line.[23] RIR 119 suffered 292 casualties, most in the mine explosion beneath the redoubt. Casualties in the 86th Brigade were 1,969, of whom 613 were killed and 81 were reported missing.[24][22]

13 November

_Division_objectives_at_Beaumont_Hamel%252C_November_1916.png.webp)

After the detonation of the Hawthorn Ridge mine on 1 July, the Royal Engineers began work on a new mine, loaded with 30,000 lb (13 long tons; 14,000 kg) of ammonal, which was placed beneath the crater of the first explosion. On 13 November 1916, two brigades of the 51st (Highland) Division attacked the first objective (green line) at Station road and Beaumont-Hamel, then the final objective (yellow line) at Frankfort Trench, with three battalions, the fourth providing carrying parties. Six minutes before zero, the leading battalion of the right brigade moved beyond the British wire and advanced when the new mine at Hawthorn Crater was blown.[25]

The Scottish troops moved past the east end of Y Ravine and reached the first objective at 6:45 a.m., with a stray party from the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division. The battalion pushed on and then withdrew slightly to Station Road. On the left, fire from Y Ravine held up the advance and at 7:00 a.m. another battalion reinforced the attack. Troops skirted the ravine to the north and early in the afternoon a battalion from the reserve brigade attacked Beaumont-Hamel from the south, joined by troops in the vicinity. The left flank brigade was held up by uncut wire to the south of Hawthorn Crater and by massed machine-gun fire north of the Auchonvillers–Beaumont-Hamel road. Two tanks were sent up, one bogging between the German front and support lines and the other north of the village. Consolidation began and three battalions were withdrawn to the German reserve line and reinforced at 9:00 p.m., while one battalion formed a defensive flank to the south, as the positions reached by the 63rd Division on the right were unknown.[26]

Aftermath

Analysis

The detonation of the Hawthorn Ridge mine, ten minutes before the general attack commenced, was not considered to be the main cause of the lack of surprise on 1 July. Lanes had been cut through the British wire, bridges had been placed over rear trenches several days earlier; a bombardment had been fired at 5:00 a.m. each morning for a week. Zero Day was not known to the Germans but the imminence of the expected attack was made evident by the springing of the mine. The lifting of the heavy artillery bombardment made it safe for the Germans to emerge and occupy the front defences, despite the surface destruction caused by the preliminary bombardment and the cutting of much of the wire.[27] The Hawthorn Ridge sector was not attacked again until 13 November, during the Battle of the Ancre. For this attack another mine was laid beneath Hawthorn Ridge, this time containing 30,000 lb (13 long tons; 14,000 kg) of explosives and Hawthorn Ridge as well as Beaumont-Hamel were captured.[28]

The 51st Division had attacked from 250 yd (230 m), obscured by fog and supported by tanks, a creeping barrage and a machine-gun barrage, which caught German infantry in the open and the Highlanders took 2,000 prisoners. An analysis by the German 1st Army concluded that the positions were lost because of weeks of bombardment, part of which was from the flank and rear of the position, although the original deep-mined dug-outs survived. The British fired a hurricane bombardment each morning to lull the defenders with familiarity and the attack began in the morning after a short period of drumfire. Fog reduced the effect of the German counter-barrage and the front-line infantry were left to repulse the first attack. The 12th Division was severely criticised and the number of recruits in the division from Polish Upper Silesia was blamed. Troops had been slow to emerge from cover and were overrun, no initiative being shown by unit leaders or the divisional command, which failed to act until the 1st Army headquarters intervened.[29]

Notes

- From 7–13 June 1915, the Second Army attacked a German salient on a 1.2 mi (1.9 km) front at Toutvent Farm near Serre, against the 52nd Division and gained 980 yd (900 m) on a 1.2 mi (2 km) front, leaving a salient known as the Heidenkopf north of the Auchonvillers–Beaumont-Hamel road, at a cost of 10,351 casualties, 1,760 being killed; German casualties were c. 4,000 men.[11]

- The plan was quashed at the headquarters of the British Expeditionary Force (GHQ) after the Inspector of Mines pointed out that the British had never managed to reach a mine crater before the Germans and that the mine should be detonated at zero hour.[15]

Footnotes

- Sheldon 2006, pp. 28–30, 40–41.

- Duffy 2007, p. 149.

- Sheldon 2006, p. 65.

- Duffy 2007, p. 143.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 100–101.

- Sheldon 2006, pp. 62, 98.

- Sheldon 2006, pp. 108–109.

- Duffy 2007, p. 122.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 100–103.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 424–425.

- Humphries & Maker 2010, p. 199.

- Sheldon 2006, pp. 112–115.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 429–431.

- Gliddon 2016, p. 78.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 430.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 429–430.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 430–431.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 426–429.

- Malins 1920, p. 163.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 431.

- Whitehead 2013, pp. 35–36.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 452.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 431–437, 452.

- Whitehead 2013, p. 57.

- Bewsher 1921, p. 100.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 152–153.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 432.

- Miles 1992, pp. 476–527.

- Duffy 2007, pp. 258–260.

References

- Bewsher, F. W. (1921). The History of the 51st (Highland) Division, 1914–1918 (online ed.). Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons. OCLC 855123826.

- Duffy, C. (2007) [2006]. Through German Eyes: The British and the Somme 1916 (Phoenix ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2202-9.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-185-5.

- Gliddon, G. (2016). Somme 1916: A Battlefield Companion. Stroud: History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-6732-7.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2010). Germany's Western Front, 1915: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. II. Waterloo Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-259-4.

- Malins, G. H. (1920). How I filmed the War: A Record of the Extraordinary Experiences of the Man Who Filmed the Great Somme Battles, etc. London: Herbert Jenkins. OCLC 246683398. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013.

- McCarthy, C. (1995) [1993]. The Somme: The Day-by-Day Account (Arms & Armour Press ed.). London: Weidenfeld Military. ISBN 978-1-85409-330-1.

- Miles, W. (1992) [1938]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: 2nd July 1916 to the End of the Battles of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-901627-76-6.

- Sheldon, J. (2006) [2005]. The German Army on the Somme 1914–1916 (Pen & Sword Military ed.). London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-1-84415-269-8.

- Whitehead, R. J. (2013). The Other Side of the Wire: The Battle of the Somme. With the German XIV Reserve Corps, 1 July 1916. II. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-907677-12-0.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, NY ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

Further reading

- Gillon, S. (2002) [1925]. The Story of 29th Division: A Record of Gallant Deeds (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Thos Nelson & Sons. ISBN 978-1-84342-265-5.

- Jones, Simon (2010). Underground Warfare 1914-1918. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-962-8.

- Whitehead, R. J. (2013a) [2010]. The Other Side of the Wire: The Battle of the Somme. With the German XIV Reserve Corps: September 1914 – June 1916. I (pbk. ed.). Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-908916-89-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt. |