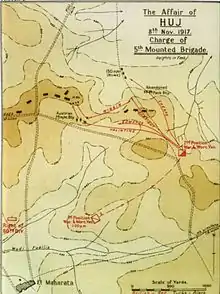

Charge at Huj

The Charge at Huj (8 November 1917), (also known by the British as the Affair of Huj), was an engagement between forces of the British Empire' Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) and the Ottoman Turkish Empire's,[nb 1] Yildirim Army Group during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War. It took place during the Pursuit phase of the Southern Palestine Offensive which eventually captured Jerusalem a month later.

| Charge at Huj | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I | |||||||

Charge at Huj, by Lady Butler | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Worcestershire Yeomanry Warwickshire Yeomanry | Part of XXI Corps | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

26 dead 40 wounded |

100+ dead 70 prisoners 11 artillery guns 4 machine guns captured | ||||||

The charge was carried out by units of the 5th Mounted Brigade, against a rearguard position of German, Austrian and Turkish artillery and infantry armed with machine guns. The charge was successful and the British captured the position, seventy prisoners, eleven pieces of artillery and four machine guns. However British casualties were heavy; of the 170 men taking part, twenty-six were killed and forty wounded. They also had 100 horses killed.

The charge is claimed to be one of the last British cavalry charges and was immortalised in a watercolour painting by the noted British artist Lady Butler.

Background

Huj is a Palestinian Arab village located 9.3 miles (15.0 km) north east of Gaza. During the Third Battle of Gaza, under pressure from the British attack, the majority of the Turkish forces from XXI Corps, had withdrawn from the area on 5 November. At around 14:00 8 November 1917, the following British forces with the 60th (2/2nd London) Division in the lead were stopped by artillery fire from a strong rearguard position on a ridge of high ground to the south of Huj.[2] The Turkish rearguard had been established to protect the withdrawal of the Eighth Army headquarters, and was composed of German, Austrian and Turkish artillery, around 300 infantry and six machine guns.[3][4] Aware that his infantry division alone would have problems taking the position, the 60th Division commander requested assistance from mounted troops.[5]

Attack

The only mounted troops in the area were 170 yeomanry - two full squadrons and two half squadrons from the Worcestershire and Warwickshire Yeomanry - part of the British 5th Mounted Brigade in the Australian Mounted Division. The squadrons manoeuvred under cover to a forming up point 1,000 yd (910 m) on the British right.[5] Advancing under cover of the terrain they got to within 300 yd (270 m) of the position, drew their swords and charged. The Warwickshire Yeomanry squadron attacked the main force of Turkish infantry, then turned and attacked the gun line.[6] The regiment's other half squadron and the Worcestershire Yeomanry squadron attacked the guns from the front,[6] while the remaining troops attacked an infantry position located at the rear behind the main force.[5]

The German and Austrian artillerymen carried on firing until the horsemen were around 20 yd (18 m) away then some took cover underneath their guns. Those who remained standing were mostly stabbed by the swords of the attacking British, while others running away from the guns escaped injury by lying on the ground.[6][7]

The only officer of the Worcestershire Yeomanry to escape uninjured Lieutenant Mercer described the charge;

Machine guns and rifles opened up on us the moment we topped the rise behind which we had formed up. I remember thinking that the sound of crackling bullets was just like hailstorm on a iron-roofed building, so you may guess what the fusillade was....A whole heap of men and horses went down twenty or thirty yards from the muzzles of the guns. The squadron broke into a few scattered horsemen at the guns and seemed to melt away completely. For a time I, at any rate, had the impression that I was the only man left alive. I was amazed to discover we were the victors.[6]

All three charges were successful and the main force of infantry withdrew leaving the guns undefended apart from their crews. The yeomanry captured seventy prisoners, eleven artillery guns and four machine guns. British casualties amounted to twenty-six men dead, including three squadron commanding officers, and forty wounded, 100 horses were also killed in the charge.[5]

Aftermath

The charge opened the way for the British forces to continue the advance, as it had destroyed the last of the Turkish strength south of the village of Huj which was captured later that day. No large groups of Turkish soldiers were cut off.[8] However both British yeomanry regiments contingents were in no position to continue the pursuit of the withdrawing Turkish forces.[4] The pursuit was further hampered by problems with watering horses and lack of supplies, both of which were hindered by the weather.[8] The British forces, from the Australian Mounted Division, did not follow up until the 9/10 November.[9]

The charge at Huj has been called "the last great charge of the British cavalry."[10] It has since been immortalised in a watercolour painting by the noted British artist Lady Butler which hangs in the Warwickshire Yeomanry Museum.[11]

Major Oscar Teichman, the Medical Officer for the Worcestershire Yeomanry writing in the Cavalry Journal in 1936 said;[5]

The Charge at Huj had it occurred in a minor war would have gone down to history like the Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava. In the Great War when gallant deeds were being enacted on all fronts almost daily it was merely an episode, but as the Official Historian remarks, for sheer bravery, the episode remains unmatched.

Visitors to the Warwickshire Yeomanry Museum located in the Court House, Jury Street, Warwick, can inspect the 75mm Model 1903 Turkish Field Gun number 488 manufactured by Friedrich Krupp, Essen, and marked to the 1/1 Warwickshire Yeomanry. This trophy gun ended up on display at Kaitangata, New Zealand circa 1921, and was finally donated by the Fox Family of Invercargill, New Zealand, to the Warwickshire Yeomanry Museum for public display in 2001. The return of the Warwickshire Yeomanry's trophy gun also served to reinforce the enduing links between 2nd New Zealand Division and the regiment which were forged in 1942, during and after the Battle of El Alamein, when the Warwickshire Yeomanry provided invaluable tank support for the New Zealand advance.

References

- Footnotes

- At the time of the First World War, the modern Turkish state did not exist, and instead it was part of the Ottoman Turkish Empire. While the terms have distinct historical meanings, within many English-language sources the term "Turkey" and "Ottoman Empire" are used synonymously, although many academic sources differ in their approaches.[1] The sources used in this article predominately use the term "Turkey".

- Citations

- Fewster, Basarin, Basarin 2003, pp.xi–xii

- Bruce, p.144

- Bruce, p.143

- Grainger, p.156

- Rickard, J. "Affair of Huj". History of war. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- Bruce, p.145

- Bruce, p.146

- Field Marshal Lord Carver, p.218.

- Wavell, p.150

- "Jack Parsons' Collection". Worcester City Museum. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- "Affair of Huj". Warwickshire Yeomanry Museum. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- Bibliography

- Bruce, Anthony (2002). The Last Crusade: The Palestine Campaign in the First World War. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5432-2.

- Field Marshal Lord Carver (2003). The National Army Museum Book of the Turkish Front. London: Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-49108-2.

- Fewster, Kevin; Basarin, Vecihi; Basarin, Hatice Hurmuz (2003). Gallipoli: The Turkish Story. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-045-5.

- Grainger, John D. (2006). The Battle for Palestine 1917. Ipswich: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-263-8.

- Wavell, Archibald Percival (1941). The Palestine Campaigns. Edinburgh: Constable. OCLC 4982054.