Cheshire

Cheshire (/ˈtʃɛʃər, -ɪər/ CHESH-ər, -eer;[2] (Welsh: Sir Gaer) archaically the County Palatine of Chester)[3] is a county in the north west of England, bordering Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south, and Flintshire and Wrexham County Borough in Wales to the west. Cheshire's county town is the City of Chester (79,645); the largest town is Warrington (210,014).[4] Other major towns include Crewe (75,000), Runcorn (61,789), Widnes (61,464), Ellesmere Port (55,715), Macclesfield (52,044), Winsford (33,700) and Northwich (19,924).[5][6][7]

Cheshire

Sir Gaer County Palatine of Chester | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motto(s): Jure Et Dignitate Gladii ("By the Right and Dignity of the Sword") | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates: 53°10′N 2°35′W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constituent country | England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Region | North West | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Established | Ancient | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (Greenwich Mean Time) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+01:00 (British Summer Time) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Members of Parliament | List of MPs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Police | Cheshire Constabulary | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The county covers 905 square miles (2,344 km2) and has a population of around 1 million. It is mostly rural, with a number of small towns and villages supporting the agricultural and other industries which produce Cheshire cheese, salt, chemicals and silk.[8]

Toponymy

Cheshire's name was originally derived from an early name for Chester, and was first recorded as Legeceasterscir in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,[9] meaning "the shire of the city of legions".[10] Although the name first appears in 980, it is thought that the county was created by Edward the Elder around 920.[10] In the Domesday Book, Chester was recorded as having the name Cestrescir (Chestershire), derived from the name for Chester at the time.[9] A series of changes that occurred as English itself changed, together with some simplifications and elision, resulted in the name Cheshire, as it occurs today.

Because of the historically close links with the land bordering Cheshire to the west, which became modern Wales, there is a history of interaction between Cheshire and North Wales. The Domesday Book records Cheshire as having two complete Hundreds (Atiscross and Exestan) that later became the principal part of Flintshire. Additionally, another large portion of the Duddestan Hundred later became known as Maelor Saesneg when it was transferred to North Wales.[11] For this and other reasons, the Welsh language name for Cheshire (Swydd Gaerlleon) is sometimes used.[12]

History

Earldom

.svg.png.webp)

After the Norman conquest of 1066 by William I, dissent and resistance continued for many years after the invasion. In 1069 local resistance in Cheshire was finally put down using draconian measures as part of the Harrying of the North. The ferocity of the campaign against the English populace was enough to end all future resistance. Examples were made of major landowners such as Earl Edwin of Mercia, their properties confiscated and redistributed amongst Norman barons.

The earldom was sufficiently independent from the kingdom of England that the 13th-century Magna Carta did not apply to the shire of Chester, so the earl wrote up his own Chester Charter at the petition of his barons.[14]

County Palatine

William I made Cheshire a county palatine and gave Gerbod the Fleming the new title of Earl of Chester. When Gerbod returned to Normandy in about 1070, the king used his absence to declare the earldom forfeit and gave the title to Hugh d'Avranches (nicknamed Hugh Lupus, or "wolf"). Because of Cheshire's strategic location on the Welsh Marches, the Earl had complete autonomous powers to rule on behalf of the king in the county palatine.

Hundreds

Cheshire in the Domesday Book (1086) is recorded as a much larger county than it is today. It included two hundreds, Atiscross and Exestan, that later became part of North Wales. At the time of the Domesday Book, it also included as part of Duddestan Hundred the area of land later known as English Maelor (which used to be a detached part of Flintshire) in Wales.[15] The area between the Mersey and Ribble (referred to in the Domesday Book as "Inter Ripam et Mersam") formed part of the returns for Cheshire.[16][17] Although this has been interpreted to mean that at that time south Lancashire was part of Cheshire,[17][18] more exhaustive research indicates that the boundary between Cheshire and what was to become Lancashire remained the River Mersey.[19][20][21] With minor variations in spelling across sources, the complete list of hundreds of Cheshire at this time are: Atiscross, Bochelau, Chester, Dudestan, Exestan, Hamestan, Middlewich, Riseton, Roelau, Tunendune, Warmundestrou and Wilaveston.[22]

Feudal baronies

There were 8 feudal baronies in Chester, the barons of Kinderton, Halton, Malbank, Mold, Shipbrook, Dunham-Massey, and the honour of Chester itself. Feudal baronies or baronies by tenure were granted by the Earl as forms of feudal land tenure within the palatinate in a similar way to which the king granted English feudal baronies within England proper. An example is the barony of Halton.[23] One of Hugh d'Avranche's barons has been identified as Robert Nicholls, Baron of Halton and Montebourg.[24]

North Mersey to Lancashire

In 1182, the land north of the Mersey became administered as part of the new county of Lancashire, resolving any uncertainty about the county in which the land "Inter Ripam et Mersam" was.[25] Over the years, the ten hundreds consolidated and changed names to leave just seven—Broxton, Bucklow, Eddisbury, Macclesfield, Nantwich, Northwich and Wirral.[26]

Principality: Merging of Palatine and Earldom

_Comitatus_(Romanis_Legionibus_et_Colonys_olim_infignis)_vera_et_abfoluta_effigies._Chriftophorus_Saxton_defcripfit._Francifcus_Scatterus_fculpfit_Anno_Dno_1577._RMG_L8558-001.jpg.webp)

In 1397 the county had lands in the march of Wales added to its territory, and was promoted to the rank of principality. This was because of the support the men of the county had given to King Richard II, in particular by his standing armed force of about 500 men called the "Cheshire Guard". As a result, the King's title was changed to "King of England and France, Lord of Ireland, and Prince of Chester". No other English county has been honoured in this way, although it lost the distinction on Richard's fall in 1399.[27]

District

Through the Local Government Act 1972, which came into effect on 1 April 1974, some areas in the north became part of the metropolitan counties of Greater Manchester and Merseyside.[28] Stockport (previously a county borough), Altrincham, Hyde, Dukinfield and Stalybridge in the north-east became part of Greater Manchester. Much of the Wirral Peninsula in the north-west, including the county boroughs of Birkenhead and Wallasey, joined Merseyside as the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral. At the same time the Tintwistle Rural District was transferred to Derbyshire. The area of south Lancashire not included within either the Merseyside or Greater Manchester counties, including Widnes and the county borough of Warrington, was added to the new non-metropolitan county of Cheshire.[29]

District and Unitary

Halton and Warrington became unitary authorities independent of Cheshire County Council on 1 April 1998, but remain part of Cheshire for ceremonial purposes and also for fire and policing.[30]

A referendum for a further local government reform connected with an elected regional assembly was planned for 2004, but was abandoned.

Unitary

As part of the local government restructuring in April 2009, Cheshire County Council and the Cheshire districts were abolished and replaced by two new unitary authorities, Cheshire East and Cheshire West and Chester. The existing unitary authorities of Halton and Warrington were not affected by the change.

Governance

Current

| Unit | Admin-HQ | Population (mid-2019 est.) | Area (km2) | Density (km2) | Head | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheshire East | Sandbach | 384,152 | 1,166 | 326 | |||

| Cheshire West & Chester | Winsford Ellesmere Port | 343,071 | 916.7 | 371 | |||

| Halton | Widnes | 129,410 | 79.08 | 1,624 | Rob Polhill | Labour | |

| Warrington | Warrington | 210,014 | 180.6 | 1,160 | Terry O'Neill | Labour | |

Cheshire has no county-wide elected local council, but it does have a Lord Lieutenant under the Lieutenancies Act 1997 and a High Sheriff under the Sheriffs Act 1887.

Local government functions apart from the Police and Fire/Rescue services are carried out by four smaller unitary authorities: Cheshire East, Cheshire West and Chester, Halton, and Warrington. All four unitary authority areas have borough status.

Policing and fire and rescue services are still provided across the county as a whole. The Cheshire Fire Authority consist of members of the four councils, while governance of Cheshire Constabulary is performed by the elected Cheshire Police and Crime Commissioner.

Winsford is a major administrative hub for Cheshire with the Police and Fire & Rescue Headquarters based in the town as well as a majority of Cheshire West and Chester Council. It was also home to the former Vale Royal Borough Council and Cheshire County Council.

Transition into a lieutenantcy

From 1 April 1974 the area under the control of the county council was divided into eight local government districts; Chester, Congleton, Crewe and Nantwich, Ellesmere Port and Neston, Halton, Macclesfield, Vale Royal and Warrington.[31][32] Halton (which includes the towns of Runcorn and Widnes) and Warrington became unitary authorities in 1998.[30][33] The remaining districts and the county were abolished as part of local government restructuring on 1 April 2009.[34] The Halton and Warrington boroughs were not affected by the 2009 restructuring.

On 25 July 2007, the Secretary of State Hazel Blears announced she was 'minded' to split Cheshire into two new unitary authorities, Cheshire West and Chester, and Cheshire East. She confirmed she had not changed her mind on 19 December 2007 and therefore the proposal to split two-tier Cheshire into two would proceed. Cheshire County Council leader Paul Findlow, who attempted High Court legal action against the proposal, claimed that splitting Cheshire would only disrupt excellent services while increasing living costs for all. A widespread sentiment that this decision was taken by the European Union long ago has often been portrayed via angered letters from Cheshire residents to local papers. On 31 January 2008 The Standard, Cheshire and district's newspaper, announced that the legal action had been dropped. Members against the proposal were advised that they may be unable to persuade the court that the decision of Hazel Blears was "manifestly absurd".

The Cheshire West and Chester unitary authority covers the area formerly occupied by the City of Chester and the boroughs of Ellesmere Port and Neston and Vale Royal; Cheshire East now covers the area formerly occupied by the boroughs of Congleton, Crewe and Nantwich, and Macclesfield. The changes were implemented on 1 April 2009.[35][36]

Congleton Borough Council pursued an appeal against the judicial review it lost in October 2007. The appeal was dismissed on 4 March 2008.[37]

Geography

Physical

Cheshire covers a boulder clay plain separating the hills of North Wales and the Peak District (the area is also known as the Cheshire Gap). This was formed following the retreat of ice age glaciers which left the area dotted with kettle holes, locally referred to as meres. The bedrock of this region is almost entirely Triassic sandstone, outcrops of which have long been quarried, notably at Runcorn, providing the distinctive red stone for Liverpool Cathedral and Chester Cathedral.

The eastern half of the county is Upper Triassic Mercia Mudstone laid down with large salt deposits which were mined for hundreds of years around Winsford. Separating this area from Lower Triassic Sherwood Sandstone to the west is a prominent sandstone ridge known as the Mid Cheshire Ridge. A 55-kilometre (34 mi) footpath,[38] the Sandstone Trail, follows this ridge from Frodsham to Whitchurch passing Delamere Forest, Beeston Castle and earlier Iron Age forts.[39]

The highest point (county top) of the historic county of Cheshire is Black Hill (582 m (1,909 ft)) near Crowden in the Cheshire Panhandle, a long eastern projection of the county along the northern side of Longdendale, and on the border with the West Riding of Yorkshire (Black Hill is now the highest point in the ceremonial county of West Yorkshire).

Within the current ceremonial county and the unitary authority of Cheshire East the highest point is Shining Tor on the Derbyshire/Cheshire border between Macclesfield and Buxton, at 559 metres (1,834 ft) above sea level. After Shining Tor, the next highest point in Cheshire is Shutlingsloe, at 506 metres (1,660 ft) above sea level. Shutlingshoe lies just to the south of Macclesfield Forest and is sometimes humorously referred to as the "Matterhorn of Cheshire" thanks to its distinctive steep profile.

Green belt

Cheshire contains portions of two green belt areas surrounding the large conurbations of Merseyside and Greater Manchester (North Cheshire Green Belt, part of the North West Green Belt) and Stoke-on-Trent (South Cheshire Green Belt, part of the Stoke-on-Trent Green Belt), these were first drawn up from the 1950s. Contained primarily within Cheshire East[40] and Chester West & Chester,[41] with small portions along the borders of the Halton[42] and Warrington[43] districts, towns and cities such as Chester, Macclesfield, Alsager, Congleton, Northwich, Ellesmere Port, Knutsford, Warrington, Poynton, Disley, Neston, Wilmslow, Runcorn, and Widnes are either surrounded wholly, partially enveloped by, or on the fringes of the belts. The North Cheshire Green Belt is contiguous with the Peak District Park boundary inside Cheshire.

Borders

The ceremonial county borders Merseyside, Greater Manchester, Derbyshire, Staffordshire and Shropshire in England along with Flintshire and Wrexham in Wales, arranged by compass directions as shown in the table. below. Cheshire also forms part of the North West England region.[44]

Demography

Population

Based on the Census of 2001, the overall population of Cheshire East and Cheshire West and Chester is 673,781, of which 51.3% of the population were male and 48.7% were female. Of those aged between 0–14 years, 51.5% were male and 48.4% were female; and of those aged over 75 years, 62.9% were female and 37.1% were male.[45] This increased to 699,735 at the 2011 Census.[46][47] The population for 2021 is forecast to be 708,000.[48]

In 2001, the population density of Cheshire East and Cheshire West and Chester was 32 people per km2, lower than the North West average of 42 people/km2 and the England and Wales average of 38 people/km2. Ellesmere Port and Neston had a greater urban density than the rest of the county with 92 people/km2.[45]

Population change

| Population totals for Cheshire East and Cheshire West and Chester | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | Year | Population | Year | Population | ||

| 1801 | 124,570 | 1881 | 303,315 | 1961 | 533,642 | ||

| 1811 | 141,672 | 1891 | 324,494 | 1971 | 605,918 | ||

| 1821 | 167,730 | 1901 | 343,557 | 1981 | 632,630 | ||

| 1831 | 191,965 | 1911 | 364,179 | 1991 | 656,050 | ||

| 1841 | 206,063 | 1921 | 379,157 | 2001 | 673,777 | ||

| 1851 | 224,739 | 1931 | 395,717 | 2011 | 699,735 | ||

| 1861 | 250,931 | 1941 | 431,335 | ||||

| 1871 | 277,123 | 1951 | 471,438 | ||||

| Pre-1974 statistics were gathered from local government areas that now comprise Cheshire Source: Great Britain Historical GIS.[49] | |||||||

Ethnicity

In 2001, ethnic white groups accounted for 98% (662,794) of the population, and 10,994 (2%) in ethnic groups other than white.

Of the 2% in non-white ethnic groups:

- 3,717 (34%) belonged to mixed ethnic groups

- 3,336 (30%) were Asian or Asian British

- 1,076 (10%) were Black or Black British

- 1,826 (17%) were of Chinese ethnic groups

- 1,039 (9%) were of other ethnic groups.[50]

Religion

In the 2001 Census, 81% of the population (542,413) identified themselves as Christian; 124,677 (19%) did not identify with any religion or did not answer the question; 5,665 (1%) identified themselves as belonging to other major world religions; and 1,033 belonged to other religions.[50]

The boundary of the Church of England Diocese of Chester follows most closely the pre-1974 county boundary of Cheshire, so it includes all of Wirral, Stockport, and the Cheshire panhandle that included Tintwistle Rural District council area.[51] In terms of Roman Catholic church administration, most of Cheshire falls into the Roman Catholic Diocese of Shrewsbury.[52]

Economy

Cheshire has a diverse economy with significant sectors including agriculture, automotive, bio-technology, chemical, financial services, food and drink, ICT, and tourism. The county is famous for the production of Cheshire cheese, salt and silk. The county has seen a number of inventions and firsts in its history.

A mainly rural county, Cheshire has a high concentration of villages. Agriculture is generally based on the dairy trade, and cattle are the predominant livestock. Land use given to agriculture has fluctuated somewhat, and in 2005 totalled 1558 km2 over 4,609 holdings.[53] Based on holdings by EC farm type in 2005, 8.51 km2 was allocated to dairy farming, with another 11.78 km2 allocated to cattle and sheep.

The chemical industry in Cheshire was founded in Roman times, with the mining of salt in Middlewich and Northwich. Salt is still mined in the area by British Salt. The salt mining has led to a continued chemical industry around Northwich, with Brunner Mond based in the town. Other chemical companies, including Ineos (formerly ICI), have plants at Runcorn. The Essar Refinery (formerly Shell Stanlow Refinery) is at Ellesmere Port. The oil refinery has operated since 1924 and has a capacity of 12 million tonnes per year.

Crewe was once the centre of the British railway industry, and remains a major railway junction. The Crewe railway works, built in 1840, employed 20,000 people at its peak, although the workforce is now less than 1,000. Crewe is also the home of Bentley cars. Also within Cheshire are manufacturing plants for Jaguar and Vauxhall Motors in Ellesmere Port. The county also has an aircraft industry, with the BAE Systems facility at Woodford Aerodrome, part of BAE System's Military Air Solutions division. The facility designed and constructed Avro Lancaster and Avro Vulcan bombers and the Hawker-Siddeley Nimrod. On the Cheshire border with Flintshire is the Broughton aircraft factory, more recently associated with Airbus.

Tourism in Cheshire from within the UK and overseas continues to perform strongly. Over 8 million nights of accommodation (both UK and overseas) and over 2.8 million visits to Cheshire were recorded during 2003.[54]

At the start of 2003, there were 22,020 VAT-registered enterprises in Cheshire, an increase of 7% since 1998, many in the business services (31.9%) and wholesale/retail (21.7%) sectors. Between 2002 and 2003 the number of businesses grew in four sectors: public administration and other services (6.0%), hotels and restaurants (5.1%), construction (1.7%), and business services (1.0%).[54] The county saw the largest proportional reduction between 2001 and 2002 in employment in the energy and water sector and there was also a significant reduction in the manufacturing sector. The largest growth during this period was in the other services and distribution, hotels and retail sectors.[54]

Cheshire is considered to be an affluent county.[55][56] However, towns such as Crewe and Winsford have significant deprivation.[57] The county's proximity to the cities of Manchester and Liverpool means counter urbanisation is common. Cheshire West has a fairly large proportion of residents who work in Liverpool and Manchester, while the town of Northwich and area of Cheshire East falls more within Manchester's sphere of influence.

Education

All four local education authorities in Cheshire operate only comprehensive state school systems. When Altrincham, Sale and Bebington were moved from Cheshire to Trafford and Merseyside in 1974, they took some former Cheshire selective schools. There are two universities based in the county, the University of Chester and the Chester campus of The University of Law. The Crewe campus of Manchester Metropolitan University was scheduled to close in 2019.[58]

Culture, media and sport

Cheshire has one Football League team, Crewe Alexandra, who play in League One. Chester, a phoenix club formed in 2010 after ex-Football League club Chester City was dissolved, competes in the National League North. Northwich Victoria, another ex-League team who were founder members of the Football League Division Two in 1892/1893, now represent Cheshire in the Northern Premier League along with Nantwich Town, Warrington Town and Witton Albion. Macclesfield Town formerly played in the National League, but went into liquidation in 2020.[59]

Warrington Wolves and the Widnes Vikings are the premier Rugby League teams in Cheshire and play in the Super League and Championship respectively. There are also numerous junior clubs in the county, including Chester Gladiators. Cheshire County Cricket Club is one of the clubs that make up the Minor counties of English and Welsh cricket. Cheshire also is represented in the highest level basketball league in the UK, the BBL, by Cheshire Phoenix (formerly Cheshire Jets). Each May, Europe's largest motorcycle event, the Thundersprint, is held in Northwich.[60]

The county has been home to many notable sports people and athletes. Many Premier League footballers have lived in Cheshire, including Dean Ashton, Seth Johnson, Michael Owen, Jesse Lingard and Wayne Rooney. Other local athletes include cricketer Ian Botham, marathon runner Paula Radcliffe, oarsman Matt Langridge, hurdler Shirley Strong, sailor Ben Ainslie, cyclist Sarah Storey and mountaineer George Mallory, who died in 1924 on Mount Everest. Cheshire has also produced a military hero in Norman Cyril Jones, a World War I flying ace who won the Distinguished Flying Cross.[61]

The county has produced several notable popular musicians, including Gary Barlow (Take That, born and raised in Frodsham), Van McCann (Catfish and the Bottlemen), Harry Styles (raised in Holmes Chapel), John Mayall (John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers),[62] Ian Astbury (The Cult), Tim Burgess (Charlatans), Ian Curtis (Joy Division) and Hooton Tennis Club. Matthew Healy, lead singer of The 1975, met his three bandmates at Wilmslow High School in Wilmslow.[63] Concert pianist Stephen Hough, singer Thea Gilmore and her producer husband Nigel Stonier also reside in Cheshire.

The county has also been home to several writers, including Hall Caine (1853–1931), popular romantic novelist and playwright; Alan Garner; Victorian novelist Elizabeth Gaskell, whose novel Cranford features her home town of Knutsford; and most famously Lewis Carroll, born and raised in Daresbury, hence the Cheshire Cat (a fictional cat popularised by Carroll in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and known for its distinctive mischievous grin). Artists from the county include ceramic artist Emma Bossons and sculptor and photographer Andy Goldsworthy. Actors from Cheshire include Tim Curry, who originated the role of Dr. Frank-N-Furter in The Rocky Horror Show; Daniel Craig, the sixth James Bond; Dame Wendy Hiller; and Lewis McGibbon, best known for his role in Millions.

Local radio stations in the county include Dee 106.3, Capital and Smooth Radio for Chester and West Cheshire, Silk FM for the east of the county, Signal 1 and The Cat 107.9 for the south, Wire FM for Warrington and Wish FM, which covers Widnes. Cheshire is one of the only counties (along with County Durham, Dorset and Rutland) that does not have its own designated BBC Radio station. The majority of the county (south and east) are covered by BBC Radio Stoke, while BBC Radio Merseyside tends to cover the west.[64] The BBC directs readers to Stoke and Staffordshire when Cheshire is selected on their website.[65] The BBC covers the west with BBC Radio Merseyside, the north and east with BBC Radio Manchester and the south with BBC Radio Stoke. There were plans to launch BBC Radio Cheshire, but those were shelved in 2007 after a lower than expected BBC licence fee settlement.

The Royal Cheshire Show, an annual agricultural show, has taken place for the last 175 years and includes exhibitions, games and competitions.[66]

Modern county emblem

As part of a 2002 marketing campaign, the plant conservation charity Plantlife chose the cuckooflower as the county flower.[67] Previously, a sheaf of golden wheat was the county emblem, a reference to the Earl of Chester's arms in use from the 12th century.

Landmarks

Prehistoric burial grounds have been discovered at The Bridestones near Congleton (Neolithic) and Robin Hood's Tump near Alpraham (Bronze Age).[68] The remains of Iron Age hill forts are found on sandstone ridges at several locations in Cheshire. Examples include Maiden Castle on Bickerton Hill, Helsby Hillfort and Woodhouse Hillfort at Frodsham. The Roman fortress and walls of Chester, perhaps the earliest building works in Cheshire remaining above ground, are constructed from purple-grey sandstone.

The distinctive local red sandstone has been used for many monumental and ecclesiastical buildings throughout the county: for example, the medieval Beeston Castle, Chester Cathedral and numerous parish churches. Occasional residential and industrial buildings, such as Helsby railway station (1849),[69] are also in this sandstone.

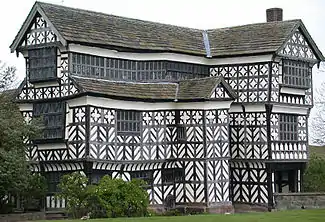

Many surviving buildings from the 15th to 17th centuries are timbered, particularly in the southern part of the county. Notable examples include the moated manor house Little Moreton Hall, dating from around 1450, and many commercial and residential buildings in Chester, Nantwich and surrounding villages.

Early brick buildings include Peover Hall near Macclesfield (1585), Tattenhall Hall (pre-1622), and the Pied Bull Hotel in Chester (17th-century). From the 18th century, orange, red or brown brick became the predominant building material used in Cheshire, although earlier buildings are often faced or dressed with stone. Examples from the Victorian period onwards often employ distinctive brick detailing, such as brick patterning and ornate chimney stacks and gables. Notable examples include Arley Hall near Northwich, Willington Hall[70] near Chester (both by Nantwich architect George Latham) and Overleigh Lodge, Chester. From the Victorian era, brick buildings often incorporate timberwork in a mock Tudor style, and this hybrid style has been used in some modern residential developments in the county. Industrial buildings, such as the Macclesfield silk mills (for example, Waters Green New Mill), are also usually in brick.

Settlements

The county is home to some of the most affluent areas of northern England, including Alderley Edge, Wilmslow, Prestbury, Tarporley and Knutsford, named in 2006 as the most expensive place to buy a house in the north of England. The former Cheshire town of Altrincham was in second place. The area is sometimes referred to as The Golden Triangle on account of the area in and around the aforementioned towns and villages.[71]

Parts of Cheshire away from the affluent areas, such as those around Blacon, Crewe, Ellesmere Port and Winsford, are among the top 5% most deprived areas in Northern England; the price of an average four-bedroom detached house in Knutsford is around £470,000 compared to £220,000 in Winsford and Ellesmere Port.

The cities and towns in Cheshire are:

| Ceremonial county | District | Centre of administration | Other towns or cities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheshire | Cheshire East (unitary) | Sandbach | Alderley Edge, Alsager, Bollington, Crewe, Congleton, Handforth, Knutsford, Macclesfield, Middlewich, Nantwich, Poynton, Wilmslow |

| Cheshire West and Chester (unitary) | Chester | Ellesmere Port, Frodsham, Malpas, Neston, Northwich, Saltney (eastern part), Tarporley, Tarvin, Winsford | |

| Halton (unitary) | Widnes | Runcorn | |

| Warrington (unitary) | Warrington | Birchwood, Culcheth, Grappenhall, Lymm |

Some settlements which were historically part of the county now fall under the counties of Derbyshire, Merseyside and Greater Manchester:[29][72][73][74]

| Derbyshire | Crowden, Newtown, Tintwistle, Whaley Bridge (western part), Woodhead |

|---|---|

| Greater Manchester | Altrincham, Bramhall, Bredbury, Cheadle, Cheadle Hulme, Dukinfield, Gatley, Hale, Hazel Grove, Hyde, Marple, Mossley (part), Partington, Romiley, Sale, Stalybridge, Stockport, Woodley, Wythenshawe |

| Merseyside | Bebington, Birkenhead, Brimstage, Bromborough, Eastham, Greasby, Heswall, Hoylake, Irby, Moreton, New Ferry, Port Sunlight, Upton, Wallasey, West Kirby |

Transport

Buses

Bus transport in Cheshire is provided by various operators. The major bus operator in the Cheshire area is Arriva North West. Other operators in Cheshire include Stagecoach Chester & Wirral, Halton Transport and Network Warrington.

There are also several operators based outside of Cheshire, who either run services wholly within the area or services which start from outside the area. Companies include Arriva Buses Wales, BakerBus, High Peak, First Greater Manchester, D&G bus and Stagecoach Manchester.

Some services are run under contract to Cheshire West and Chester, Cheshire East, Borough of Halton and Warrington Councils.

Railway

The main railway line through the county is the West Coast Main Line. Trains on the main London to Scotland line call at Crewe (in the south of the county) and Warrington Bank Quay (in the north of the county). Trains stop at Crewe and Runcorn on the Liverpool branch of the WCML; Crewe and Macclesfield are each hourly stops on the two Manchester branches.

The major interchanges are:

- Crewe (the biggest station in Cheshire) for trains to London Euston, Glasgow Central, Edinburgh Waverley, Manchester Piccadilly and Liverpool Lime Street (via the WCML). Trains on other routes travel to Wales, the Midlands (Birmingham, Stoke and Derby) as well as suburban services to Manchester Piccadilly, Chester and Liverpool Lime Street.

- Warrington stations (Central and Bank Quay) for suburban services to Manchester Piccadilly, Chester and Liverpool Lime Street and regional express services to North Wales, London, Scotland, Yorkshire, the East Coast and the East Midlands

- Chester for urban services (via Merseyrail) to Liverpool Central, suburban services to Manchester, Warrington, Wrexham General and rural Cheshire and express services to Llandudno, Holyhead, Birmingham, the West Midlands, London and Cardiff and, from May 2019, to Leeds.

In the east of Cheshire, Macclesfield station is served by Avanti West Coast, CrossCountry and Northern, on the Manchester–London line. Services from Manchester to the south coast frequently stop at Macclesfield.

Road

Cheshire has 3,417 miles (5,499 km) of roads, including 214 miles (344 km) of the M6, M62, M53 and M56 motorways; there are 23 interchanges and four service areas. The M6 motorway at the Thelwall Viaduct carries 140,000 vehicles every 24 hours.[75]

Waterways

Chester Weir on the River Dee

Chester Weir on the River Dee Canal cutting by Chester city walls

Canal cutting by Chester city walls

The Cheshire canal system includes several canals originally used to transport the county's industrial products (mostly chemicals). Nowadays they are mainly used for tourist traffic. The Cheshire Ring is formed from the Rochdale, Ashton, Peak Forest, Macclesfield, Trent and Mersey and Bridgewater canals.

The Manchester Ship Canal is a wide, 36-mile (58 km) stretch of water opened in 1894. It consists of the rivers Irwell and Mersey made navigable to Manchester for seagoing ships leaving the Mersey estuary. The canal passes through the north of the county via Runcorn and Warrington.

List of rivers and canals

See also

- Outline of England

- Cheshire (UK Parliament constituency), historical list of MPs for Cheshire constituency

- Healthcare in Cheshire

- Custos Rotulorum of Cheshire – Keepers of the Rolls

- Lord Lieutenant of Cheshire

- High Sheriff of Cheshire

- Cheshire Cat

- Cheshire cheese

- List of parks and open spaces in Cheshire

- Places to visit, stay, shop and eat in Cheshire

- Constable of Chester

Notes and references

Notes

- "No. 62943". The London Gazette. 13 March 2020. p. 5161.

- "Cheshire" Archived 21 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- "Relationships / unit history of Cheshire". A Vision of Britain through Time website. Archived from the original on 6 May 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- "Cheshire County Council". Cheshire County Council website. Archived from the original on 27 February 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- "Cheshire County Council Map" (PDF). Cheshire County Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- "Towns & Villages in Cheshire - Visitcheshire.com". www.visitcheshire.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- "2011 Census results: Overview Profile: Northwich Town Council; downloaded from Cheshire West and Chester: Population Profiles, 16 May 2019". Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Ingham, A. (1920). Cheshire: Its Traditions and History. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Harris, B. E. and Thacker, A. T. (1987). p. 237.

- Crosby, A. (1996). page 31.

- Harris, B.E. and Thacker, A.T. (1987). pp. 340–341.

- Welsh dictionary entry for Cheshire. www.geriadur.net website (Welsh-English / English-Welsh On-line Dictionary). Department of Welsh, University of Wales, Lampeter. Accessed on 21 February 2008

- "Wrexham County Borough Council: The Princes and the Marcher Lords". Wrexham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- Hewitt, Herbert James (1929). Mediaeval Cheshire: An Economic and Social History of Cheshire in the Reigns of the Three Edwards. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 9.

- Davies, R. (2000). The Age of Conquest: Wales 1063–1415.

- Morgan (1978). pp.269c–301c,d.

- Sylvester (1980). p. 14.

- Roffe (2000)

- Harris and Thacker (1987) write on page 252:

Certainly there were links between Cheshire and south Lancashire before 1000, when Wulfric Spot held lands in both territories. Wulfric's estates remained grouped together after his death when they were left to his brother Aelfhelm, and indeed there still seems to have been some kind of connexion in 1086, when south Lancashire was surveyed together with Cheshire by the Domesday commissioners. Nevertheless, the two territories do seem to have been distinguished from one another in some way and it is not certain that the shire-moot and the reeves referred to in the south Lancashire section of Domesday were the Cheshire ones.

- Phillips and Phillips (2002); pp. 26–31.

- Crosby, A. (1996) writes on page 31:

The Domesday Survey (1086) included south Lancashire with Cheshire for convenience, but the Mersey, the name of which means 'boundary river' is known to have divided the kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia and there is no doubt that this was the real boundary.

- Harris, B. E., and Thacker, A. T. (1987); pages 340–341.

- Sanders, I.J. English Baronies, a Study of their Origin and Descent 1086–1327, Oxford, 1960, p.138, refers to the "Lord" of Halton being the hereditary constable of the County Palatine of Chester, but omits Halton from both his lists of English feudal baronies

- Crosby, A. A History of Cheshire; Norman Chapter

- George, D. (1991). Lancashire. Archived from the original on 1 September 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "Cheshire ancient divisions". Vision of Britain website. Archived from the original on 6 May 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- Davies, R. R. 'Richard II and the Principality of Chester' in The Reign of Richard II: Essays in Honour of May McKisack, ed. F. R. H. Du Boulay and Caroline Baron (1971)

- Jones, B.; et al. (2004). Politics UK.

- Local Government Act 1972

- "The Cheshire (Boroughs of Halton and Warrington) (Structural Change) Order 1996". Office of Public Sector Information. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- Vision of Britain Archived 6 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine – Divisions of Cheshire

- Cheshire County Council Archived 5 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine – Map of Cheshire districts

- "The Lord Lieutenant of Cheshire". Cheshire County Council. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- "Cheshire (Structural Changes) Order 2008". Opsi.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 17 May 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "BBC News, 25 July 2007 – County split into two authorities". BBC News. 25 July 2007. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "The Cheshire (Structural Changes) Order 2008". Office of Public Sector Information. Archived from the original on 23 December 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- "Unitary legal fight over in 60 seconds". LocalGov.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- Archived 2 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Walking Cheshire's Sandstone Trail". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011.

- "Cheshire East Council Green Belt Assessment Update 2015 – Final Consolidated Report". Cheshire East Council.

- "Local Plan – Green Belt Study Part One". Cheshire West and Chester Council.

- "Widnes and Hale Green Belt Study" (PDF). www3.halton.gov.uk. Halton Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Warrington Borough Council Green Belt Assessment Final Report Final – 21 October 2016" (PDF). www.warrington.gov.uk. Warrington Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Local Authorities". Government Offices of the North West. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- "Census 2001 – Population" (PDF). Cheshire Census Consortium. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- "2011 Census: Helping tomorrow take shape". Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

A population estimate for Cheshire East of 370,127

- "2011 Census Cheshire West". Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

329,608 residents in Cheshire West and Chester

- "CCC Long Term Population Forecasts" (PDF). Cheshire County Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- A Vision of Britain through Time. "Cheshire Modern (post 1974) County: Total Population". Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- "Key Statistics Interim Profile" (PDF). Cheshire County Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- Chester Diocese (Church of England). Archived 31 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Official website. Accessed on 30 September 2007.

- Diocese of Shrewsbury (Roman Catholic). Archived 29 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Official website. Accessed on 30 September 2007.

- "Agricultural Holdings – Land and Employment – Cheshire – 2002 to 2005" (PDF). Cheshire County Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2007. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- "Cheshire Economy (page 64)" (PDF). Cheshire County Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- "Top Ten Most Affluent Villages in the UK". The Telegraph. 17 February 2017. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- "Chester Named Top Place to Live in UK". The Chester Chronicle. 21 September 2015. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- "Area Profile" (PDF). Cheshire East Council. Cheshire East Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- McCann, Phil (25 November 2016). "Crewe's university campus set to shut". BBC. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- "Silkmen expelled from National League". BBC Sport. 29 September 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- "The Thundersprint". Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- Shores, et al, p. 217.

- John Mayall biographical details. Archived 26 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine www.johnmayall.com website. Accessed on 21 February 2008.

- Bono, Salvatore. "Speaking With Your New Favorite Band – The 1975". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- "BBC Radio Cheshire – Radio – Digital Spy Forums". Forums.digitalspy.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "BBC News – Stoke & Staffordshire". Bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "About The Royal Cheshire County Show | The Royal Cheshire County Show". The Royal Cheshire County Show 2016. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- "Things to do – Plantlife in your area – North-west England". Plantlife. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- "Cheshire County Council: Revealing Cheshire's Past". .cheshire.gov.uk. 1 September 2004. Archived from the original on 17 November 2004. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1261746)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1137030)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Why Cheshire fat cats smile". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2006.

- Chandler, J. (2001). Local Government Today.

- "Cheshire ancient county boundaries". Vision of Britain website. Archived from the original on 6 May 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- "Cheshire 1974 boundaries". Vision of Britain website. Archived from the original on 6 May 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- "Road policing". Cheshire Police website. Archived from the original on 5 November 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

Bibliography

- Crosby, A. (1996). A History of Cheshire. (The Darwen County History Series.) Chichester, UK: Phillimore & Co ISBN 0-85033-932-4.

- Harris, B. E., and Thacker, A. T. (1987). The Victoria History of the County of Chester. (Volume 1: Physique, Prehistory, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Domesday). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-722761-9.

- Morgan, P. (Ed.) (1978). Domesday Book. Volume 26: Cheshire. Chichester, Sussex: Phillmore and Company Limited. ISBN 0-85033-140-4.

- Phillips, A. D. M., and Phillips, C. B. (Eds.) (2002). A New Historical Atlas of Cheshire. Chester, UK: Cheshire County Council and Cheshire Community Council Publications Trust. ISBN 0-904532-46-1.

- Shores, Christopher; Franks, Norman; Guest, Russell (1990). Above the Trenches: A Complete Record of the Fighter Aces and Units of the British Empire Air Forces 1915–1920. Grub Street. ISBN 0-948817-19-4, ISBN 978-0-948817-19-9.

- Sylvester, D. (1980). A History of Cheshire, (The Darwen County History Series.) (Second Edition, original publication date, 1971). London and Chichester, UK: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0-85033-384-9.

Further reading

- Beck, J. (1969). Tudor Cheshire. (Volume 7 of Cheshire Community Council Series: A History of Cheshire). Series Editor: J. J. Bagley. Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council.

- Bu'Lock, J. D. (1972). Pre-Conquest Cheshire 383–1066. (Volume 3 of Cheshire Community Council Series: A History of Cheshire). Series Editor: J. J. Bagley. Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council.

- Dore, R.N. (1966). The Civil Wars in Cheshire. (Volume 8 of Cheshire Community Council Series: A History of Cheshire). Series Editor: J. J. Bagley. Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council.

- Driver, J. T. (1971). Cheshire in the Later Middle Ages 1399–1540. (Volume 6 of Cheshire Community Council Series: A History of Cheshire). Series Editor: J. J. Bagley. Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council.

- Harris, B. E. (1979). 'The Victoria History of the County of Chester. (Volume 2). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-722749-X.

- Harris, B. E. (1980). 'The Victoria History of the County of Chester. (Volume 3). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-722754-6.

- Hewitt, H. J. (1967). Cheshire Under the Three Edwards. (Volume 5 of Cheshire Community Council Series: A History of Cheshire). Series Editor: J. J. Bagley. Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council.

- Higham, N. J. (1993). The Origins of Cheshire. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3160-5.

- Hodson, J. H. (1978). Cheshire, 1660–1780: Restoration to Industrial Revolution. (Volume 9 of Cheshire Community Council Series: A History of Cheshire). Series editor: J. J. Bagley. Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council. ISBN 0-903119-11-0.

- Husain, B. M. C. (1973). Cheshire Under the Norman Earls 1066–1237. (Volume 4 of Cheshire Community Council Series: A History of Cheshire). Series editor: J. J. Bagley. Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council.

- Morgan, V., and Morgan, P. (2004). Prehistoric Cheshire. Ashbourne, Derbyshire: Landmark Publishing Company. ISBN 1-84306-140-6.

- Scard, G. (1981). Squire and Tenant: Rural Life in Cheshire 1760–1900. (Volume 10 of Cheshire Community Council Series: A History of Cheshire). Series editor: J. J. Bagley. Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council. ISBN 0-903119-13-7.

- Scholes, R. (2000). The Towns and Villages of Britain: Cheshire. Wilmslow, Cheshire: Sigma Press. ISBN 1-85058-637-3.

- Starkey, H. F. (1990). "Old Runcorn". Halton Borough Council. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). - Sylvester. D., and Nulty, G. (1958). The Historical Atlas of Cheshire. (Third Edition) Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council.

- Thompson, F. H. (1965). Roman Cheshire. (Volume 2 of Cheshire Community Council Series: A History of Cheshire). Series Editor: J. J. Bagley. Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council.

- Tigwell, R. E. (1985). Cheshire in the Twentieth Century. (Volume 11 of Cheshire Community Council Series: A History of Cheshire). Series Editor: J. J. Bagley. Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council.

- Varley, W. J. (1964). Cheshire Before the Romans. (Volume 1 of Cheshire Community Council Series: A History of Cheshire). Series Editor: J. J. Bagley. Chester, UK: Cheshire Community Council.

- Youngs, F. A. (1991). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England. (Volume 1: Northern England). London: Royal Historical Society. ISBN 0-86193-127-0.

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)