Conjugate acid

A conjugate acid, within the Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, is a chemical compound formed when an acid donates a proton (H+) to a base—in other words, it is a base with a hydrogen ion added to it, as in the reverse reaction it loses a hydrogen ion. On the other hand, a conjugate base is what is left over after an acid has donated a proton during a chemical reaction. Hence, a conjugate base is a species formed by the removal of a proton from an acid, as in the reverse reaction it is able to gain a hydrogen ion.[1] Because some acids are capable of releasing multiple protons, the conjugate base of an acid may itself be acidic.

In summary, this can be represented as the following chemical reaction:

- Acid + Base ⇌ Conjugate Base + Conjugate Acid

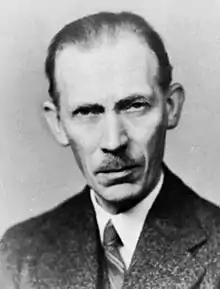

Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted and Martin Lowry introduced the Brønsted–Lowry theory, which proposed that any compound that can transfer a proton to any other compound is an acid, and the compound that accepts the proton is a base. A proton is a nuclear particle with a unit positive electrical charge; it is represented by the symbol H+ because it constitutes the nucleus of a hydrogen atom,[2] that is, a hydrogen cation.

A cation can be a conjugate acid, and an anion can be a conjugate base, depending on which substance is involved and which acid–base theory is the viewpoint. The simplest anion which can be a conjugate base is the solvated electron whose conjugate acid is the atomic hydrogen.

Acid-base reactions

In an acid-base reaction, an acid plus a base reacts to form a conjugate base plus a conjugate acid:

Conjugates are formed when an acid loses a hydrogen proton or a base gains a hydrogen proton. Refer to the following figure:

We say that the water molecule is the conjugate acid of the hydroxide ion after the latter received the hydrogen proton donated by ammonium. On the other hand, ammonia is the conjugate base for the acid ammonium after ammonium has donated a hydrogen ion towards the production of the water molecule. We can also refer to OH- as a conjugate base of H

2O, since the water molecule donates a proton towards the production of NH+

4 in the reverse reaction, which is the predominating process in nature due to the strength of the base NH

3 over the hydroxide ion. Based on this information, it is clear that the terms "Acid", "Base", "conjugate acid", and "conjugate base" are not fixed for a certain chemical species; but are interchangeable according to the reaction taking place.

Strength of conjugates

The strength of a conjugate acid is directly proportional to its dissociation constant. If a conjugate acid is strong, its dissociation will have a higher equilibrium constant and the products of the reaction will be favored. The strength of a conjugate base can be seen as the tendency of the species to "pull" hydrogen protons towards itself. If a conjugate base is classified as strong, it will "hold on" to the hydrogen proton when in solution and its acid will not dissociate.

If a species is classified as a strong acid, its conjugate base will be weak.[3] An example of this case would be the dissociation of hydrochloric acid HCl in water. Since HCl is a strong acid (it dissociates to a great extent), its conjugate base (Cl−

) will be a weak conjugate base. Therefore, in this system, most H+

will be in the form of a hydronium ion H

3O+

instead of attached to a Cl− anion and the conjugate base will be weaker than a water molecule.

On the other hand, if a species is classified as a weak acid its conjugate base will not necessarily be a strong base. Consider that acetate, the conjugate base of acetic acid, has a base dissociation constant (Kb) of approximately 5.6x10−10, making it a weak base. In order for a species to have a strong conjugate base it has to be a very weak acid, like water for example.

Identifying conjugate acid-base pairs

The acid and conjugate base as well as the base and conjugate acid are known as conjugate pairs. When finding a conjugate acid or base, it is important to look at the reactants of the chemical equation. In this case, the reactants are the acids and bases, and the acid corresponds to the conjugate base on the product side of the chemical equation; as does the base to the conjugate acid on the product side of the equation.

To identify the conjugate acid, look for the pair of compounds that are related. The acid–base reaction can be viewed in a before and after sense. The before is the reactant side of the equation, the after is the product side of the equation. The conjugate acid in the after side of an equation gains a hydrogen ion, so in the before side of the equation the compound that has one less hydrogen ion of the conjugate acid is the base. The conjugate base in the after side of the equation lost a hydrogen ion, so in the before side of the equation, the compound that has one more hydrogen ion of the conjugate base is the acid.

Consider the following acid–base reaction:

- HNO

3 + H

2O → H

3O+

+ NO−

3

Nitric acid (HNO

3) is an acid because it donates a proton to the water molecule and its conjugate base is nitrate (NO−

3). The water molecule acts as a base because it receives the Hydrogen Proton and its conjugate acid is the hydronium ion (H

3O+

).

| Equation | Acid | Base | Conjugate base | Conjugate acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HClO 2 + H 2O → ClO− 2 + H 3O+ | HClO 2 | H 2O | ClO− 2 | H 3O+ |

| ClO− + H 2O → HClO + OH− | H 2O | ClO− | OH− | HClO |

| HCl + H 2PO− 4 → Cl− + H 3PO 4 | HCl | H 2PO− 4 | Cl− | H 3PO 4 |

Applications

One use of conjugate acids and bases lies in buffering systems, which include a buffer solution. In a buffer, a weak acid and its conjugate base (in the form of a salt), or a weak base and its conjugate acid, are used in order to limit the pH change during a titration process. Buffers have both organic and non-organic chemical applications. For example, besides buffers being used in lab processes, our blood acts as a buffer to maintain pH. The most important buffer in our bloodstream is the carbonic acid-bicarbonate buffer, which prevents drastic pH changes when CO

2 is introduced. This functions as such:

Furthermore, here is a table of common buffers.

Buffering agent pKa Useful pH range Citric acid 3.13, 4.76, 6.40 2.1 - 7.4 Acetic acid 4.8 3.8 - 5.8 KH2PO4, 7.2 6.2 - 8.2 CHES 9.3 8.3–10.3 Borate 9.24 8.25 - 10.25

A second common application with an organic compound would be the production of a buffer with acetic acid. If acetic acid, a weak acid with the formula CH

3COOH, was made into a buffer solution, it would need to be combined with its conjugate base CH

3COO−

in the form of a salt. The resulting mixture is called an acetate buffer, consisting of aqueous CH

3COOH and aqueous CH

3COONa. Acetic acid, along with many other weak acids, serve as useful components of buffers in different lab settings, each useful within their own pH range.

An example with an inorganic compound would be the medicinal use of lactic acid’s conjugate base known as lactate in Lactated Ringer's solution and Hartmann's solution. Lactic acid has the formula C

3H

6O

6 and its conjugate base is used in intravenous fluids that consist of sodium and potassium cations along with lactate and chloride anions in solution with distilled water. These fluids are commonly isotonic in relation to human blood and are commonly used for spiking up the fluid level in a system after severe blood loss due to trauma, surgery, or burn injury.

Table of acids and their conjugate bases

Tabulated below are several examples of acids and their conjugate bases; notice how they differ by just one proton (H+ ion). Acid strength decreases and conjugate base strength increases down the table.

| Acid | Conjugate base |

|---|---|

| H 2F+ Fluoronium ion |

HF Hydrogen fluoride |

| HCl Hydrochloric acid | Cl− Chloride ion |

| H2SO4 Sulfuric acid | HSO− 4 Hydrogen sulfate ion |

| HNO3 Nitric acid | NO− 3 Nitrate ion |

| H3O+ Hydronium ion | H2O Water |

| HSO− 4 Hydrogen sulfate ion |

SO2− 4 Sulfate ion |

| H3PO4 Phosphoric acid | H2PO− 4 Dihydrogen phosphate ion |

| CH3COOH Acetic acid | CH3COO− Acetate ion |

| HF Hydrofluoric acid | F− Fluoride ion |

| H2CO3 Carbonic acid | HCO− 3 Hydrogen carbonate ion |

| H2S Hydrosulfuric acid | HS− Hydrogen sulfide ion |

| H2PO− 4 Dihydrogen phosphate ion |

HPO2− 4 Hydrogen phosphate ion |

| NH+ 4 Ammonium ion |

NH3 Ammonia |

| H2O Water (pH=7) | OH− Hydroxide ion |

| HCO− 3 Hydrogencarbonate (bicarbonate) ion |

CO2− 3 Carbonate ion |

Table of bases and their conjugate acids

In contrast, here is a table of bases and their conjugate acids. Similarly, base strength decreases and conjugate acid strength increases down the table.

| Base | Conjugate acid |

|---|---|

| C 2H 5NH 2 Ethylamine |

C 2H 5NH+ 3 Ethylammonium ion |

| CH 3NH 2 Methylamine |

CH 3NH+ 3 Methylammonium ion |

| NH 3 Ammonia |

NH+ 4 Ammonium ion |

| C 5H 5N Pyridine |

C 5H 6N+ Pyridinium |

| C 6H 5NH 2 Aniline |

C 6H 5NH+ 3 Phenylammonium ion |

| C 6H 5CO− 2 Benzoate ion |

C 6H 6CO 2 Benzoic acid |

| F− Fluoride ion |

HF Hydrogen fluoride |

| PO3− 4 Phosphate ion |

HPO2− 4 Hydrogen phosphate ion |

| OH− Hydroxide ion | H2O Water (neutral, pH 7) |

References

- Zumdahl, Stephen S., & Zumdahl, Susan A. Chemistry. Houghton Mifflin, 2007, ISBN 0618713700

- "Brønsted–Lowry theory | chemistry". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-02-25.

- "Strength of Conjugate Acids and Bases Chemistry Tutorial". www.ausetute.com.au. Retrieved 2020-02-25.