DV

DV is a format for storing digital videos. It was launched in 1995 with joint efforts of leading producers of video camera recorders. It is the foundation of the MiniDV format.

The original DV specification, known as Blue Book, was standardized within the IEC 61834 family of standards. These standards define common features such as physical videocassettes, recording modulation method, magnetization, and basic system data in part 1. Part 2 describes the specifics of video systems supporting 525-60 for NTSC and 625-50 for PAL.[1] The IEC standards are available as publications sold by IEC and ANSI.

In 2003,[2] DV was joined by a successor format HDV, which used the same tape format with a different video codec. Some cameras at the time had the ability to switch between DV and HDV recording modes.

All tape-based and optical disc-based video formats have become obsolete as cameras recording on memory cards and solid-state drives have become the norm since they offer increased ruggedness, speed and storage space which allows for higher bitrate and resolution video, although the DV encoding standard is sometimes still used.

DV compression

DV uses lossy compression of video while audio is stored uncompressed.[3] An intraframe video compression scheme is used to compress video on a frame-by-frame basis with the discrete cosine transform (DCT).

Closely following the ITU-R Rec. 601 standard, DV video employs interlaced scanning with the luminance sampling frequency of 13.5 MHz. This results in 480 scanlines per complete frame for the 60 Hz system, and 576 scanlines per complete frame for the 50 Hz system. In both systems the active area contains 720 pixels per scanline, with 704 pixels used for content and 16 pixels on the sides left for digital blanking. The same frame size is used for 4:3 and 16:9 frame aspect ratios, resulting in different pixel aspect ratios for fullscreen and widescreen video.[4][5]

Prior to the DCT compression stage, chroma subsampling is applied to the source video in order to reduce the amount of data to be compressed. Baseline DV uses 4:1:1 subsampling in its 60 Hz variant and 4:2:0 subsampling in the 50 Hz variant. Low chroma resolution of DV (compared to higher-end digital video formats) is a reason this format is sometimes avoided in chroma keying applications, though advances in chroma keying techniques and software have made producing quality keys from DV material possible.[6][7]

Audio can be stored in either of two forms: 16-bit Linear PCM stereo at 48 kHz sampling rate (768 kbit/s per channel, 1.5 Mbit/s stereo), or four nonlinear 12-bit PCM channels at 32 kHz sampling rate (384 kbit/s per channel, 1.5 MBit/s for four channels). In addition, the DV specification also supports 16-bit audio at 44.1 kHz (706 kbit/s per channel, 1.4 Mbit/s stereo), the same sampling rate used for CD audio.[8] In practice, the 48 kHz stereo mode is used almost exclusively.

Digital Interface Format

The audio, video, and metadata are packaged into 80-byte Digital Interface Format (DIF) blocks which are multiplexed into a 150-block sequence. DIF blocks are the basic units of DV streams and can be stored as computer files in raw form or wrapped in such file formats as Audio Video Interleave (AVI), QuickTime (QT) and Material Exchange Format (MXF).[9][10] One video frame is formed from either 10 or 12 such sequences, depending on scanning rate, which results in a data rate of about 25 Mbit/s for video, and an additional 1.5 Mbit/s for audio. When written to tape, each sequence corresponds to one complete track.[4]

Baseline DV employs unlocked audio. This means that the sound may be +/- ⅓ frame out of sync with the video. However, this is the maximum drift of the audio/video synchronization; it is not compounded throughout the recording.

Variants

Sony and Panasonic created their proprietary versions of DV aimed toward professional & broadcast users, which use the same compression scheme, but improve on robustness, linear editing capabilities, color rendition and raster size.

All DV variants except for DVCPRO Progressive are recorded to tape within interlaced video stream. Film-like frame rates are possible by using pulldown. DVCPRO HD supports native progressive format when recorded to P2 memory cards.

DVCPRO

DVCPRO, also known as DVCPRO25, is a variation of DV developed by Panasonic and introduced in 1995 for use in electronic news gathering (ENG) equipment.

Unlike baseline DV, DVCPRO uses locked audio and 4:1:1 chroma subsampling for both 50 Hz and 60 Hz variants to decrease generation losses.[11] Audio is available in 16-bit/48 kHz precision.

When recorded to tape, DVCPRO uses wider track pitch - 18 μm vs. 10 μm of baseline DV, which reduces the chance of dropout errors during recording. Two extra longitudinal tracks provide support for audio cue and for timecode control. Tape is transported 80% faster compared to baseline DV, resulting in shorter recording time. Long Play mode is not available.

DVCAM

In 1996 Sony responded with its own professional version of DV called DVCAM.[12]

Like DVCPRO, DVCAM uses locked audio, which prevents audio synchronization drift that may happen on DV if several generations of copies are made.[13]

When recorded to tape, DVCAM uses 15 μm track pitch, which is 50% wider compared to baseline. Accordingly, tape is transported 50% faster, which reduces recording time by one third compared to regular DV. Because of the wider track and track pitch, DVCAM has the ability to do a frame-accurate insert edit, while regular DV may vary by a few frames on each edit compared to the preview.

DVCPRO50

DVCPRO50 was introduced by Panasonic in 1997 for high-value electronic news gathering and digital cinema, and is often described as two DV codecs working in parallel.

The DVCPRO50 doubles the coded video data rate to 50 Mbit/s. This has the effect of cutting total record time of any given storage medium in half. Chroma resolution is improved by using 4:2:2 chroma subsampling.

DVCPRO50 was used in many productions where high definition video was not required. For example, BBC used DVCPRO50 to record high-budget TV series, such as Space Race (2005) and Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire (2006).

A similar format, D-9, offered by JVC, uses videocassettes with the same form-factor as VHS.

Comparable high quality standard definition digital tape formats include Sony's Digital Betacam, launched in 1993, and MPEG IMX, launched in 2001.

DVCPRO Progressive

DVCPRO Progressive was introduced by Panasonic for news gathering, sports journalism and digital cinema. It offered 480 or 576 lines of progressive scan recording with 4:2:0 chroma subsampling and four 16-bit 48 kHz PCM audio channels. Like HDV-SD, it was meant as an intermediate format during the transition time from standard definition to high definition video.[14][15]

The format offered six modes for recording and playback: 16:9 progressive (50 Mbit/s), 4:3 progressive (50 Mbit/s), 16:9 interlaced (50 Mbit/s), 4:3 interlaced (50 Mbit/s), 16:9 interlaced (25 Mbit/s), 4:3 interlaced (25 Mbit/s).[16]

The format has been superseded with DVCPRO HD.

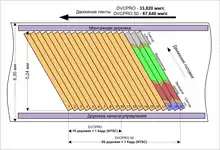

DVCPRO HD

DVCPRO HD, also known as DVCPRO100 is a high-definition video format that can be thought of as four DV codecs that work in parallel. Video data rate depends on frame rate and can be as low as 40 Mbit/s for 24 frame/s mode and as high as 100 Mbit/s for 50/60 frame/s modes. Like DVCPRO50, DVCPRO HD employs 4:2:2 color sampling.

DVCPRO HD uses smaller raster size than broadcast high definition television: 960x720 pixels for 720p, 1280x1080 for 1080/59.94i and 1440x1080 for 1080/50i. Similar horizontal downsampling (using rectangular pixels) is used in many other magnetic tape-based HD formats such as HDCAM. To maintain compatibility with HDSDI, DVCPRO100 equipment upsamples video during playback.

Variable framerates (from 4 to 60 frame/s) are available on VariCam camcorders. DVCPRO HD equipment offers backward compatibility with older DV/DVCPRO formats.

When recorded to tape in standard-play mode, DVCPRO HD uses the same 18 μm track pitch as other DVCPRO flavors. A long play variant, DVCPRO HD-LP, doubles the recording density by using 9 μm track pitch.

DVCPRO HD is codified as SMPTE 370M; the DVCPRO HD tape format is SMPTE 371M, and the MXF Op-Atom format used for DVCPRO HD on P2 cards is SMPTE 390M.

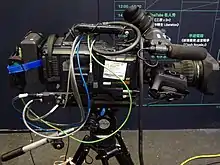

While technically DVCPRO HD is a direct descendant of DV, it is used almost exclusively by professionals. Tape-based DVCPRO HD cameras exist only in shoulder mount variant.

A similar format, Digital-S (D-9 HD), was offered by JVC and used videocassettes with the same form-factor as VHS.

The main competitor to DVCPRO HD was HDCAM, offered by Sony. It uses a similar compression scheme but at higher bitrate.

Progressive recording

Tape-based DV variants, except for DVCPRO Progressive, do not support native progressive recording, therefore progressively acquired video is recorded within interlaced video stream using pulldown. The same technique is used in television industry to broadcast movies. Progressive-scan DV camcorders for 60 Hz market record 24-frame/s video using 2-3 pulldown and 30-frame/s video using 2-2 pulldown. Progressive-scan DV camcorders for 50 Hz market record 25-frame/s video using 2-2 pulldown.

Progressive video can be recorded with interlaced delivery in mind, in which case high-frequency information between fields is blended to suppress interline twitter. If the goal is progressive-scan distribution like Web videos, progressive-scan DVD-video or filmout, then no filtering is applied. Video recorded with 2-2 pulldown and no vertical filtering is conceptually identical to progressive segmented frame.

Consumer-grade DV camcorders capable of progressive recording usually offer only 2-2 pulldown scheme because of its simplicity. Such a video can be edited as either interlaced or progressive and does not require additional processing aside of treating every pair of fields as one complete frame. Canon and Panasonic call this format Frame Mode, while Sony calls it Progressive Scan recording. 24 frame/s recording is available only on professional DV camcorders and requires pulldown removal if editing at native frame rate is required.

DVCPRO HD supports native progressive recording at 50 or 60 frame/s in 720p mode. To record video acquired at 24, 25 or 30 frame/s frame repeating is used. Frame repeating is similar to field repeating used in interlaced video, and is also called pulldown sometimes.

Recording media

Magnetic tape

| |

DV cassettes: DVCAM-L, DVCPRO-M, MiniDV | |

| Media type | Video recording media |

|---|---|

| Encoding | DV |

| Read mechanism | Helical scan |

| Write mechanism | Helical scan |

| Usage | Camcorders |

| Released | 1995 |

DV was originally designed for recording onto magnetic tape. Tape is enclosed into videocassette of four different sizes: small, medium, large and extra-large. All DV cassettes use ¼ inch (6.35 mm) wide tape.

Small cassettes, also known as S-size or MiniDV cassettes, had been intended for amateur use, but have become accepted in professional productions as well. MiniDV cassettes are used for recording baseline DV, DVCAM, and HDV. These cassettes come in lengths up to about 13 GB for 63 minutes of DV or HDV video.[17] When recording in DVCAM, these cassettes hold up to 41 minutes of video. There are some 83-minute versions but these use thinner tape than the 63-minute ones, and Panasonic advised against playing these cassettes in DVCPRO decks.

Medium or M-size cassettes, which are about the size of Video8/Hi8/Digital8 cassettes, are used in professional Panasonic equipment and are often called DVCPRO tapes. Panasonic video recorders that accept medium cassette can play back from and record to medium cassette in different flavors of DVCPRO format; they will also play small cassettes containing DV or DVCAM recording via an adapter. These cassettes come in lengths up to 66 minutes for DVCPRO, 33 minutes for DVCPRO50 and DVCPRO HD-LP, and 16 minutes for the original DVCPRO HD.

Large or L-size cassettes are accepted by most standalone DV tape recorders and are used in many shoulder-mount camcorders. Consumer DV VCRs were made which could record onto these cassettes, but despite the capabilities of the format, these never gained widespread popularity among consumers. The L-size cassette can be used in both Sony and Panasonic equipment; nevertheless, they are often called DVCAM tapes. Older Sony decks would not play large cassettes with DVCPRO recordings, but newer models can play these and M-size DVCPRO cassettes. These cassettes come in lengths up to 276 minutes of DV or HDV video (or 184 minutes for DVCAM) which is more data than what VHS, S-VHS, D-VHS, Video8, Hi8 and Digital8 are capable of, and unlike the VHS formats and Digital8 which use thinner tape for their longest-length variants, the 276-minute DV cassette is able to use the same tape as its shorter-length variants. On the DVCPRO side, these cassettes have nearly double the tape capacity of their M-size counterparts, with lengths up to 126 minutes for DVCPRO, 64 minutes for DVCPRO50 and DVCPRO HD-LP, and 32 minutes for the original DVCPRO HD. A thin-tape 184/92/46-minute version was also released.

Extra-large cassettes or XL-size have been designed for use in Panasonic equipment and are sometimes called DVCPRO XL. These cassettes are not widespread, and only two models of standalone Panasonic tape recorders can accept them. Each XL-size cassette holds nearly double the amount of tape as the full-length L-size cassettes with a capacity of 252 minutes of DVCPRO video or 126 minutes of DVCPRO50 or DVCPRO HD-LP video.

Technically, any DV cassette can record any variant of DV video. Nevertheless, manufacturers often label cassettes with DV, DVCAM, DVCPRO, DVCPRO50 or DVCPRO HD and indicate recording time with regards to the label posted. Cassettes labeled as DV indicate recording time of baseline DV; another number can indicate recording time of Long Play DV. Cassettes labeled as DVCPRO have a yellow tape door and indicate recording time when DVCPRO25 is used; with DVCPRO50 the recording time is half, with DVCPRO HD it is a quarter. Cassettes labeled as DVCPRO50 have a blue tape door and indicate recording time when DVCPRO50 is used. Cassettes labeled as DVCPRO HD have a red tape door and indicate recording time when DVCPRO HD-LP format is used; a second number may be used for DVCPRO HD recording, which will be half as long.

Panasonic stipulated use of a particular magnetic-tape formulation—metal particle (MP)—as an inherent part of its DVCPRO family of formats. Regular DV tape uses Metal Evaporate (ME) formulation (which, as the name suggests, uses physical vapor deposition to deposit metal onto the tape[18]), which was pioneered for use in Hi8 camcorders. Early Hi8 ME tape was plagued with excessive dropouts, which forced many shooters to switch to more expensive MP tape. After the technology improved, the dropout rate was greatly reduced, nevertheless Panasonic deemed ME formulation not robust enough for professional use. Tape-based professional Panasonic DVCPRO camcorders and decks only record onto DVCPRO-branded cassettes, effectively preventing use of ME tape.

File-based media

With proliferation of tapeless camcorder video recording, DV video can be recorded on optical discs, solid state flash memory cards and hard disk drives and used as computer files. In particular:

- Sony XDCAM family of cameras can record DV onto either Professional Disc or SxS memory cards.

- Panasonic DVCPRO HD and AVC-Intra camcorders can record DV (as well as DVCPRO) onto P2 cards.

- Some Panasonic AVCHD camcorders (AG-HMC80, AG-AC130, AG-AC160) record DV video onto Secure Digital memory cards.

- JVC GY-HM750 can be set to standard definition mode and in this case will record '.AVI or .MOV SD legacy format' video onto SDHC cards. For clarity - and contrary to what has previously been written, the camera does not natively support SxS memory cards, has no slots for them and requires an optional add-on recorder (or 'adapter' as JVC call it) to achieve this - basically this camera is an 'XDCAM EX' High definition unit and the add-on SxS recorder was only made available to achieve better compatibility in facilities which were Sony based.

- Most DV and HDV camcorders can feed live DV stream over IEEE 1394 interface to an external file-based recorder.

Video is stored either as native DIF bitstream or wrapped into an audio/video container such as AVI, QuickTime or MXF.

- DV-DIF is the raw form of DV video. The files usually have extensions *.dv or *.dif.

- DV-AVI is Microsoft's implementation of DV video file, which is wrapped into an AVI container. Two variants of wrapping are available: with Type 1 the multiplexed audio and video is saved into the video section of a single AVI file, with Type 2 video and audio are saved as separate streams in an AVI file (one video stream and one to four audio streams). This container is used primarily on Windows-based computers, though Sony offers two tapeless recorders, the HDD-based HVR-DR60[19] and the CompactFlash-based HVR-MRC1K,[20] for use with DV/HDV camcorders that can record in DV-AVI format either making a file-based copy of the tape or bypassing tape recording altogether. Panasonic AVCHD camcorders use Type 2 DV-AVI for recording DV video onto Secure Digital memory card.[21]

- QuickTime-DV is DV video wrapped into QuickTime container. This container is used primarily on Apple computers.

- MXF-DV wraps DV video into MXF container, which is presently used on P2-based camcorders (Panasonic) and on XDCAM/XDCAM EX camcorders (Sony).

Connectivity

Nearly all DV camcorders and decks have IEEE 1394 (FireWire, i.LINK) ports for digital video transfer. This is usually a two-way port, so that DV video data can be output to a computer (DV-out), or input from either a computer or another camcorder (DV-in). The DV-in capability makes it possible to copy edited DV video from a computer back onto tape, or make a lossless copy between two mutually connected DV camcorders. However, models made for sale in the European Union usually had the DV-in capability disabled in the firmware by the manufacturer because the camcorder would be classified by the EU as a video recorder and would therefore attract higher duty;[22] a model which only had DV-out could be sold at a lower price in the EU.

When video is captured onto a computer it is stored in a container file, which can be either raw DV stream, AVI, WMV or QuickTime. Whichever container is used, the video itself is not re-encoded and represents a complete digital copy of what has been recorded onto tape. If needed, the video can be recorded back to tape to create a full and lossless copy of the original footage.

Some camcorders also feature a USB 2.0 port for computer connection. This port is usually used for transferring still images, but not for video transfer. Camcorders that offer video transfer over USB usually do not deliver full DV quality - usually it is 320x240 video, except for the Sony DCR-PC1000 camcorder and some Panasonic camcorders that provide transfer of a full-quality DV stream via USB by using the UVC protocol. Full-quality DV can also be captured via USB by using separate hardware that receives DV data from the camcorder over a FireWire cable and forwards it without any transcoding to the computer via a USB cable[23] - this can be particularly useful for capturing on modern laptop computers which frequently do not have a FireWire port or expansion slot but always have USB ports.

High end cameras and VTRs may have additional professional outputs such as SDI, SDTI or analog component video. All DV variants have a time code, but some older or consumer computer applications fail to take advantage of it.

Usage

The high quality of DV images, especially when compared to Video8 and Hi8 which were vulnerable to an unacceptable number of video dropouts and "hits", prompted the acceptance by mainstream broadcasters of material shot on DV. The low costs of DV equipment and their ease of use put such cameras in the hands of a new breed of videojournalists. Programs such as TLC's Trauma: Life in the E.R. and ABC News's Hopkins: 24/7 were shot on DV.

DVCPRO HD was the preferred high definition standard of BBC Factual.[24]

Application software support

Most DV players, editors and encoders only support the basic DV format, but not its professional versions. The exception to this being that most (not all) consumer Sony miniDV equipment will play mini-DVCAM tapes. DV Audio/Video data can be stored as raw DV data stream file (data is written to a file as the data is received over FireWire, file extensions are .dv and .dif) or the DV data can be packed into container files (ex: Microsoft AVI, Apple MOV). The DV meta-information is preserved in both file types.

Most Windows video software only supports DV in AVI containers, as they use Microsoft's avifile.dll, which only supports reading avi files. Mac OS X video software support both AVI and MOV containers.

- Apple Inc.'s iMovie: iMovie allows importing from HDV cameras since iMovie HD, which import in full quality, and DV cameras since iMovie 1, which decodes to half of the original quality, to preserve processing power.

- Apple Inc.'s Final Cut Pro: Final Cut Pro allows importing from all DV, HDV, and AVCHD (using the Apple Intermediate Codec or ProRes) cameras. It supports rewinding, fast-forwarding, pausing, stopping and playing from the computer.

- Apple Inc.'s QuickTime Player: QuickTime by default only decodes DV to half of the resolution to preserve processing power for editing capabilities. However, in the "Pro" version the setting "High Quality" under "Show Movie Properties" enables full resolution playback.

- The VLC media player (Free software): full decoding quality

- MPlayer (also with GUI under Windows and Mac OS X): full decoding quality

- muvee Technologies autoProducer 4.0: Allows editing using FireWire IEEE 1394

- Quasar DV codec (libdv) - open source DV codec for Linux

- DVswitch - open source linear editor for DV streams, with live streaming capabilities

- DV Analyzer - open source tool to analyze and detect errors and inconsistencies in DV streams (also extracts and reports the original recording date/time):

Mixing tapes from different manufacturers

There was considerable controversy solely based on hearsay over whether or not using tapes from different manufacturers could lead to dropouts.[25][26] Initially this was suggested around the conception of mostly MiniDV tapes in the mid to late 90s as the only two manufacturers of MiniDV tapes (Sony, who produce their tapes solely under the Sony brand; and Panasonic, who produce their own tapes under their Panasonic brand and outsources for TDK, Canon, etc.) used two different lubrication types for their cameras - Sony uses a 'wet' lubricant ('ME' or 'Metal Evaporated'), while Panasonic uses a 'dry' lubricant ('MP' or 'Metal Particle').

Though the controversy still remain standard practice for encouraging casual and professional camera operators alike not to mix brands of tapes (as the different lubrication formulations can cause or encourage tape wear if not cleaned by a cleaning cassette), no significant problems have occurred for the last few years - meaning that switching tapes is acceptable, though sticking to one brand (and cleaning the heads with a cleaning cassette before doing so) is highly recommended.

A research undertaken by Sony claimed that there was no hard evidence of the above statement. The only evidence claimed was that using ME tapes in equipment designed for MP tapes can cause tape damage and hence dropouts.[27] Sony has done a significant amount of internal testing to simulate head clogs as a result of mixing tape lubricants, and has been unable to recreate the problem. Sony recommends using cleaning cassettes once every 50 hours of recording or playback. For those who are still skeptical, Sony recommends cleaning video heads with a cleaning cassette before trying another brand of tape.

References

- Recording – Helical-scan digital videocassette recording system using 6,35 mm magnetic tape for consumer use

- "HV10 - Canon Camera Museum". global.canon. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "DV Q&A Our Expert Answers Your Questions". Videomaker magazine. Videomaker, Inc. October 1999.

- "DVCAM format overview" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011.

- "Digital Video and Field Order". dvmp.co.uk.

- fxguide.com

- "The DV, DVCAM, & DVCPRO Formats -- tech details, FAQ, and links". adamwilt.com.

- Puhovski, Nenad (April 2000). "DV – A SUCCESS STORY". www.stanford.edu. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- "DV-DIF (Digital Video Digital Interface Format)". digitalpreservation.gov.

- "DV format". debian.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- "The DV, DVCAM, & DVCPRO Formats -- tech details, FAQ, and links". adamwilt.com.

- https://cvp.com/pdf/sony_dvcam_family.pdf

- "BBC Training: DV Tape Formats". Archived from the original on 11 June 2011.

- "Caporale Studios Shoots Feature Films with Panasonic 480p DVCPRO50 Camcorder". dvformat.com.

- 480p production systems Archived 21 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "AJ-PD900WP Operating instructions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- "Appendix B: Data Rates and Storage Needs for Various Digital Formats". The Filmmaker's Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide for the Digital Age (PDF). WestCityFilms.com (4th ed.).

- http://www.totalmedia.com/content/trivia-and-tips/what-is-metal-evaporated-tape.html

- "HVR-DR60 HDV hard disk recorder".

- "HVR-MRC1K Memory Recording Unit".

- "Panasonic AG-HMC80 operating instructions" (PDF).

- "Why is the DV input disabled on most digital camcorders sold in Europe?". 5 April 2001. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "How to Capture DV video via USB". dvmp.co.uk.

- HD at BBC

- "DV Tape FAQ". zenera.com.

- Adam J. Wilt. "Adam Wilt's Video Tidbits". adamwilt.com.

- The Truth About Tape Lubricant

External links

- Adam Wilt's DV page with in-depth technical information

- Technical Documentation on the storage of DV data in AVI files:

- DV Analyzer - open source tool to analyze and detect errors and inconsistencies in DV streams (also extracts and reports the original recording date/time):