Doris Lessing

Doris May Lessing CH OMG (née Tayler; 22 October 1919 – 17 November 2013) was a British-Zimbabwean (Rhodesian) novelist. She was born to British parents in Iran, where she lived until 1925. Her family then moved to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), where she remained until moving in 1949 to London, England. Her novels include The Grass Is Singing (1950), the sequence of five novels collectively called Children of Violence (1952–1969), The Golden Notebook (1962), The Good Terrorist (1985), and five novels collectively known as Canopus in Argos: Archives (1979–1983).

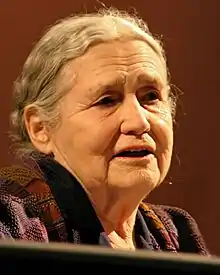

Doris Lessing | |

|---|---|

Lessing at the Lit Cologne literary festival in 2006 | |

| Born | Doris May Tayler 22 October 1919 Kermanshah, Iran |

| Died | 17 November 2013 (aged 94) London, England |

| Pen name | Jane Somers |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | British |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom |

| Period | 1950–2013 |

| Genre | Novel, short story, biography, drama, libretto, poetry |

| Literary movement | Modernism, postmodernism, Sufism, socialism, feminism, scepticism science fiction |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards | |

| Spouse | Frank Charles Wisdom

(m. 1939; div. 1943) |

| Children |

|

| Website | |

| dorislessing | |

Lessing was awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature. In awarding the prize, the Swedish Academy described her as "that epicist of the female experience, who with scepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilisation to scrutiny".[2] Lessing was the oldest person ever to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.[3][4][5]

In 2001, Lessing was awarded the David Cohen Prize for a lifetime's achievement in British literature. In 2008, The Times ranked her fifth on a list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945".[6]

Life

Early life

Lessing was born Doris May Tayler in Kermanshah, Iran, on 22 October 1919, to Captain Alfred Tayler and Emily Maude Tayler (née McVeagh), both British subjects.[7] Her father, who had lost a leg during his service in World War I, met his future wife, a nurse, at the Royal Free Hospital in London where he was recovering from his amputation.[8][9] The couple moved to Iran, for Alfred to take a job as a clerk for the Imperial Bank of Persia.[10][11]

In 1925, the family moved to the British colony of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to farm maize and other crops on about 1,000 acres (400 ha) of bush that Alfred bought. In the rough environment, his wife Emily aspired to lead an Edwardian lifestyle. It might have been possible had the family been wealthy; in reality, they were short of money and the farm delivered very little income.[12]

As a girl Doris was educated first at the Dominican Convent High School, a Roman Catholic convent all-girls school in the Southern Rhodesian capital of Salisbury (now Harare).[13] Then followed a year at Girls High School in Salisbury.[14] She left school at age 13 and was self-educated from then on. She left home at 15 and worked as a nursemaid. She started reading material that her employer gave her on politics and sociology[9] and began writing around this time.

In 1937, Doris moved to Salisbury to work as a telephone operator, and she soon married her first husband, civil servant Frank Wisdom, with whom she had two children (John, 1940–1992, and Jean, born in 1941), before the marriage ended in 1943.[9] Lessing left the family home in 1943, leaving the two children with their father.[1]

Move to London; political views

After the divorce, Doris's interest was drawn to the community around the Left Book Club, an organisation she had joined the year before.[12][15] It was here that she met her future second husband, Gottfried Lessing. They married shortly after she joined the group, and had a child together (Peter, 1946-2013), before they divorced in 1949. She did not marry again.[9] Lessing also had a love affair with RAF serviceman John Whitehorn (brother of journalist Katharine Whitehorn), who was stationed in Southern Rhodesia, and wrote him ninety letters between 1943 and 1949.[16]

Lessing moved to London in 1949 with her younger son, Peter, to pursue her writing career and socialist beliefs, but left the two older children with their father Frank Wisdom in South Africa. She later said that at the time she saw no choice: "For a long time I felt I had done a very brave thing. There is nothing more boring for an intelligent woman than to spend endless amounts of time with small children. I felt I wasn't the best person to bring them up. I would have ended up an alcoholic or a frustrated intellectual like my mother."[17]

As well as campaigning against nuclear arms, she was an active opponent of apartheid, which led her to being banned from South Africa and Rhodesia in 1956 for many years.[18] In the same year, following the Soviet invasion of Hungary, she left the British Communist Party.[19] In the 1980s, when Lessing was vocal in her opposition to Soviet actions in Afghanistan,[20] she gave her views on feminism, communism and science fiction in an interview with The New York Times.[10]

On 21 August 2015, a five-volume secret file on Lessing built up by the British intelligence agencies, MI5 and MI6, was made public[21] and placed in The National Archives. The file, which contains documents that are redacted in parts, shows Lessing was under surveillance by British spies for around twenty years, from the early-1940s onwards. Her associations with Communism and her anti-racist activism are reported[22] to be the reasons for the secret service interest in Lessing.

Literary career

At the age of fifteen, Lessing began to sell her stories to magazines.[23] Her first novel, The Grass Is Singing, was published in 1950.[12] The work that gained her international attention, The Golden Notebook, was published in 1962.[11] By the time of her death, she had published more than 50 novels, some under a pseudonym.[24]

In 1982, Lessing wrote two novels under the literary pseudonym Jane Somers to show the difficulty new authors face in trying to get their work printed. The novels were rejected by Lessing's UK publisher, but later accepted by another English publisher, Michael Joseph, and in the US by Alfred A. Knopf. The Diary of a Good Neighbour[25] was published in Britain and the US in 1983, and If the Old Could in both countries in 1984,[26] both as written by Jane Somers. In 1984, both novels were re-published in both countries (Viking Books publishing in the US), this time under one cover, with the title The Diaries of Jane Somers: The Diary of a Good Neighbour and If the Old Could, listing Doris Lessing as author.[27]

Lessing declined a damehood (DBE) in 1992 as an honour linked to a non-existent Empire; she had declined an OBE in 1977.[28] Later she accepted appointment as a Companion of Honour at the end of 1999 for "conspicuous national service".[29] She was also made a Companion of Literature by the Royal Society of Literature.[30]

In 2007, Lessing was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.[31] She received the prize at the age of 88 years 52 days, making her the oldest winner of the literature prize at the time of the award and the third-oldest Nobel laureate in any category (after Leonid Hurwicz and Raymond Davis Jr.).[32][33] She also was only the eleventh woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature by the Swedish Academy in its 106-year history.[34] In 2017, just 10 years later, her Nobel medal was put up for auction.[35][36] Previously only one Nobel medal for literature was sold at auction, for André Gide in 2016.[36]

Lessing was out shopping for groceries when the Nobel Prize announcement came. Arriving home to a gathering of reporters, she exclaimed, "Oh Christ!"[37] "I've won all the prizes in Europe, every bloody one, so I'm delighted to win them all. It's a royal flush."[38] She titled her Nobel Lecture On Not Winning the Nobel Prize and used it to draw attention to global inequality of opportunity, and to suggest that fiction writers can be involved in redressing those inequalities. Lessing wrote that "it is our imaginations which shape us, keep us, create us – for good and for ill. It is our stories that will recreate us, when we are torn, hurt, even destroyed."[39] The lecture was later published in a limited edition to raise money for children made vulnerable by HIV/AIDS. In a 2008 interview for the BBC's Front Row, she stated that increased media interest after the award had left her without time or energy for writing.[40] Her final book, Alfred and Emily, appeared in 2008.

Illness and death

During the late-1990s, Lessing suffered a stroke[41] which stopped her from travelling during her later years.[42] She was still able to attend the theatre and opera.[41] She began to focus her mind on death, for example asking herself if she would have time to finish a new book.[18][41] She died on 17 November 2013, aged 94, at her home in London, predeceased by her two sons, but was survived by her daughter, Jean, who lives in South Africa.[43]

She was remembered with a humanist funeral service.[44]

Fiction

Lessing's fiction is commonly divided into three distinct phases.

During her Communist phase (1944–56) she wrote radically about social issues, a theme to which she returned in The Good Terrorist (1985). Doris Lessing's first novel, The Grass Is Singing, as well as the short stories later collected in African Stories, are set in Southern Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe) where she was then living.

This was followed by a psychological phase from 1956 to 1969, including the Golden Notebook and the "Children of Violence" quartet.

Third came the Sufi phase, explored in her 70s work, and in the Canopus in Argos sequence of science fiction (or as she preferred to put it "space fiction") novels and novellas.

Lessing's Canopus sequence received a mixed reception from mainstream literary critics. John Leonard praised her 1980 novel The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five in The New York Times,[46] but in 1982 John Leonard wrote in reference to The Making of the Representative for Planet 8 that "[o]ne of the many sins for which the 20th century will be held accountable is that it has discouraged Mrs. Lessing... She now propagandises on behalf of our insignificance in the cosmic razzmatazz,"[47] to which Lessing replied: "What they didn't realise was that in science fiction is some of the best social fiction of our time. I also admire the classic sort of science fiction, like Blood Music, by Greg Bear. He's a great writer."[48] She attended the 1987 World Science Fiction Convention as its Writer Guest of Honor. Here she made a speech in which she described her dystopian novel Memoirs of a Survivor as "an attempt at an autobiography."[49]

The Canopus in Argos novels present an advanced interstellar society's efforts to accelerate the evolution of other worlds, including Earth. Using Sufi concepts, to which Lessing had been introduced in the mid-1960s by her "good friend and teacher" Idries Shah,[45] the series of novels also uses an approach similar to that employed by the early 20th century mystic G. I. Gurdjieff in his work All and Everything. Earlier works of "inner space" fiction like Briefing for a Descent into Hell (1971) and Memoirs of a Survivor (1974) also connect to this theme. Lessing's interest had turned to Sufism after coming to the realisation that Marxism ignored spiritual matters, leaving her disillusioned.[50]

Lessing's novel The Golden Notebook is considered a feminist classic by some scholars,[51] but notably not by the author herself, who later wrote that its theme of mental breakdowns as a means of healing and freeing one's self from illusions had been overlooked by critics. She also regretted that critics failed to appreciate the exceptional structure of the novel. She explained in Walking in the Shade that she modelled Molly partly on her good friend Joan Rodker, the daughter of the modernist poet and publisher John Rodker.[52]

Lessing did not like being pigeon-holed as a feminist author. When asked why, she explained:

What the feminists want of me is something they haven't examined because it comes from religion. They want me to bear witness. What they would really like me to say is, 'Ha, sisters, I stand with you side by side in your struggle toward the golden dawn where all those beastly men are no more.' Do they really want people to make oversimplified statements about men and women? In fact, they do. I've come with great regret to this conclusion.

Doris Lessing Society

The Doris Lessing Society is dedicated to supporting the scholarly study of Lessing's work. The formal structure of the Society dates from January 1977, when the first issue of the Doris Lessing Newsletter was published. In 2002 the Newsletter became the academic journal Doris Lessing Studies. The Society also organises panels at the Modern Languages Association (MLA) annual Conventions and has held two international conferences in New Orleans in 2004 and Leeds in 2007.[53]

Archives

Lessing's literary archive is held by the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, at the University of Texas at Austin. The 45 archival boxes of Lessing's materials at the Ransom Center contain nearly all of her extant manuscripts and typescripts up to 1999. Original material for Lessing's early books is assumed not to exist because she kept none of her early manuscripts.[54] The McFarlin Library at the University of Tulsa holds a smaller collection.[55]

The University of East Anglia's British Archive for Contemporary Writing holds Doris Lessing's personal archive: a vast collection of professional and personal correspondence, including the Whitehorn letters, a collection of love letters from the 1940s, written when Lessing was still living in Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia). The collection also includes forty years of personal diaries. Some of the archive remains embargoed during the writing of Lessing's official biography.[56]

Awards

- Somerset Maugham Award (1954)

- Prix Médicis étranger (1976)

- Austrian State Prize for European Literature (1981)

- Shakespeare-Preis der Alfred Toepfer Stiftung F. V. S., Hamburg (1982)

- WH Smith Literary Award (1986)

- Palermo Prize (1987)

- Premio Internazionale Mondello (1987)

- Premio Grinzane Cavour (1989)

- James Tait Black Memorial Prize for biography (1995)

- Los Angeles Times Book Prize (1995)

- Premi Internacional Catalunya (1999)[57]

- Order of the Companions of Honour (1999)

- Companion of Literature of the Royal Society of Literature (2000)

- David Cohen Prize (2001)

- Premio Príncipe de Asturias (2001)

- S.T. Dupont Golden PEN Award (2002)[58]

- Nobel Prize in Literature (2007)

- Order of Mapungubwe: Category II Gold (2008)[59]

List of works

|

|

References

- Stanford, Peter (22 November 2013). "Doris Lessing: A mother much misunderstood". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "NobelPrize.org". Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- Crown, Sarah."Doris Lessing wins Nobel prize", The Guardian, 11 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- Editors at BBC. "Author Lessing wins Nobel honour", BBC News, 23 October 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- Marchand, Philip. "Doris Lessing oldest to win literature award". Toronto Star, 12 October 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- (5 January 2008). "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945". Archived from the original on 25 April 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2008.. The Times. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- Hazelton, Lesley (11 October 2007). "Golden Notebook' Author Lessing Wins Nobel Prize". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- Carole Klein. "Doris Lessing". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- Liukkonen, Petri. "Doris Lessing". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008.

- Hazelton, Lesley (25 July 1982). "Doris Lessing on Feminism, Communism and 'Space Fiction'". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- "Author Lessing wins Nobel honour". BBC News. 11 October 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- "Biography". A Reader's Guide to The Golden Notebook and Under My Skin. HarperCollins. 1995. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- Carol Simpson Stern. Doris Lessing Biography. biography.jrank.org. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- Lessing, Doris (1994). Under My Skin: Volume One of My Autobiography, to 1949. London: Harper Collins. p. 147. ISBN 000255545X.

- Brief Chronology. A Home for the Highland Cattle & The Antheap. Broadview Press. 2003. ISBN 9781551113630. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- Flood, Alison (22 October 2008). "Doris Lessing donates revelatory letters to university". The Guardian.

- "Lowering the Bar. When bad mothers give us hope" Archived 30 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Newsweek, 6 May 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- Peter Guttridge (17 November 2013). "Doris Lessing: Nobel Prize-winning author whose work ranged from social and political realism to science fiction". The Independent. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Miller, Stephen (17 November 2013). "Nobel Author Doris Lessing Dies at 94". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- "Doris Lessing blows the veil of romanticism off Afghanistan", The Christian Science Monitor, 14 January 1988.

- Shirbon, Estelle, "British spies reveal file on Nobel-winner Doris Lessing", Reuters, 21 August 2015.

- Norton-Taylor, Richard, "MI5 spied on Doris Lessing for 20 years, declassified documents reveal", The Guardian, 21 August 2015.

- Lessing, Doris. "Biography (From the pamphlet: A Reader's Guide to The Golden Notebook & Under My Skin, HarperPerennial, 1995)".

- Kennedy, Maev (17 November 2013). "Doris Lessing dies aged 94". The Guardian.

- "The Diary of a Good Neighbour by Doris Lessing". Doris Lessing. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "If the Old Could by Doris Lessing". www.dorislessing.org.

- Hanft, Adam. "When Doris Lessing Became Jane Somers and Tricked the Publishing World (And Possibly Herself In the Process)". The Huffington Post, 10 November 2007. Updated 25 May 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- Flood, Alison (22 October 2008). "Doris Lessing donates revelatory letters to university". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "Doris Lessing interview". BBC Radio. Archived from the original (Audio) on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- "Companions of Literature list". Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- Rich, Motoko and Lyall, Sarah. "Doris Lessing Wins Nobel Prize in Literature". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- Hurwicz won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science in 2007 aged 90. Davis received the 2002 Physics Prize at 88 years 57 days. Their birth dates are shown in their biographies at the Nobel Prize web site, which states that the awards are given annually on 10 December.

- Pierre-Henry Deshayes. "Doris Lessing wins Nobel Literature Prize". Herald Sun. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- Reynolds, Nigel. "Doris Lessing wins Nobel prize for literature". The Telegraph. Retrieved 15 October 2007. Archived 14 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Valuable Books and Manuscripts". Cristies. 13 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- Alison Flood (7 December 2017). "Doris Lessing's Nobel medal goes up for auction". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- "Lessing's Legacy of Political Literature", CBS News, 12 October 2007.

- Hinckley, David. "Doris Lessing wins Nobel Prize for Literature". Daily News (New York). Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- "The Nobel Prize in Literature 2007". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- "Lessing: Nobel win a 'disaster'". BBC News. 11 May 2008. Retrieved 11 May 2008.

- Raskin, Jonah (June 1999). "The Progressive Interview: Doris Lessing". The Progressive (reprint). dorislessing.org. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Helen T. Verongos (17 November 2013). "Doris Lessing, Novelist Who Won 2007 Nobel, is Dead at 94". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "Author Doris Lessing dies aged 94", BBC. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "Humanists UK launches first ever funeral tribute archive". Humanists UK. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- Lessing, Doris. "On the Death of Idries Shah (excerpt from Shah's obituary in the London The Daily Telegraph)". dorislessing.org. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- https://www.nytimes.com/1980/03/27/archives/books-of-the-times-gentle-book.html Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- Leonard, John (7 February 1982). "The Spacing Out of Doris Lessing". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- Doris Lessing: Hot Dawns, interview by Harvey Blume in Boston Book Review

- "Guest of Honor Speech", in Worldcon Guest of Honor Speeches, edited by Mike Resnick and Joe Siclari (Deerfield, IL: ISFIC Press, 2006), p. 192.

- "Postcolonial Nostalgias: Writing, Representation and Memory", Volume 31 of Routledge research in postcolonial literatures, Dennis Walder, Taylor & Francis ltd, 2010, p92. ISBN 9780203840382.

- "Fresh Air Remembers 'Golden Notebook' Author Doris Lessing". NPR. 18 November 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- Scott, Lynda, "Lessing's Early and Transitional Novels: The Beginnings of a Sense of Selfhood", Deepsouth, vol. 4, no. 1 (Autumn 1998). Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "Doris Lessing Society". Doris Lessing Society.

- "Harry Ransom Center Holds Archive of Nobel Laureate Doris Lessing". hrc.utexas.edu. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- "Doris Lessing manuscripts". lib.utulsa.edu. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "Doris Lessing Archive". University of Tulsa. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- "Memòria del Departament de Cultura 1999" (PDF) (in Catalan). Generalitat de Catalunya. 1999. p. 38. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "Golden Pen Award, official website". English PEN. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- "National Orders Recipients 2008". South African History Online. 28 October 2008. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

Further reading

- Diski, Jenny (2016). In gratitude. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-408-87992-4.

- Fahim, Shadia S. (1995). Doris Lessing: Sufi Equilibrium and the Form of the Novel. Basingstoke, UK/New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan/St. Martins Press. ISBN 0-312-10293-3.

- Galin, Müge (1997). Between East and West: Sufism in the Novels of Doris Lessing. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-3383-8.

- Raschke, Debrah; Sternberg Perrakis, Phyllis; Singer, Sandra (2010). Doris Lessing: Interrogating the Times. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-1136-6.

- Ridout, Alice (2010). Contemporary Women Writers Look Back: From Irony to Nostalgia. London: Continuum International Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-3023-5.

- Ridout, Alice; Watkins, Susan (2009). Doris Lessing: Border Crossings. London: Continuum International Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-0416-8.

- Skille, Nan Bentzen (1977). Fragmentation and Integration. A Critical Study of Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook. University of Bergen.

- Watkins, Susan (2010). Doris Lessing. Manchester UP. ISBN 978-0-7190-7481-3.

- Wolfe, Graham (2019). Theatre-Fiction in Britain from Henry James to Doris Lessing: Writing in the Wings. Routledge. ISBN 9781000124361.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Doris Lessing. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Doris Lessing |

- Transcript of Doris Lessing's "Dame" rejection letter to the John Major Government

- Doris Lessing, Excerpts 'On Cats'

- Doris Lessing homepage created by Jan Hanford

- Doris Lessing at IMDb

- Doris Lessing at Curlie

- "The shadow of the fifth": patterns of exclusion in Doris Lessing’s The Fifth Child (Anne-Laure Brevet)

- List of Works

- Doris Lessing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Doris Lessing at British Council: Literature

- Doris Lessing on Nobelprize.org

with the Nobel Lecture December 7, 2007 On not winning the Nobel Prize

with the Nobel Lecture December 7, 2007 On not winning the Nobel Prize - Doris Lessing at Web of Stories (videos)

- Joyce Carol Oates on Doris Lessing

- Thomas Frick (Spring 1988). "Doris Lessing, The Art of Fiction No. 102". The Paris Review. Spring 1988 (106).

- Doris Lessing's papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Doris Lessing Archive, University of East Anglia

- University of Tulsa McFarlin Library's inventory of Doris Lessing manuscripts housed in Special Collections

- Doris Lessing Page at Guardian Unlimited

- Doris Lessing Society

- Doris Lessing, Author Who Swept Aside Convention, Is Dead at 94, by Helen T Virongos & Emma G. Fitzsimmons, New York Times, 2013-11-18. (Page A1, 2013-11-17).

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Cats in Literature – Doris Lessing