Fishery

A fishery is the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life.[1] Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farms, both in fresh water (about 10% of all catch) and the oceans (about 90%). About 500 million people worldwide are economically dependent on fisheries. 171 million tonnes of fish were produced in 2016, but overfishing is an increasing problem -- causing declines in some populations.[2] Recreational fishing is popular in many locations, particularly North America, Europe, New Zealand, and Australia.

Because of their economic and social importance, fisheries are governed by complex fishery management practices and legal regimes, that vary widely among country. Historically, fisheries were treated with a first-come first serve approach; however threats by human overfishing and environmental issues, have required increased regulation of fisheries to prevent conflict and increase profitable economic activity on the fishery. Modern jurisdiction over fisheries is often established by a mix of international treaties and local laws.

Declining fish populations, human pollution in the oceans, and destruction of important coastal ecosystems has introduced increasing uncertainty in important fisheries worldwide, threatening economic security and food security in many parts of the world. These challenges are further complicated by the changes in the ocean caused by climate change, which may extend the range of some fisheries while dramatically reducing the sustainability of other fisheries. International attention to these issues has been captured in Sustainable Development Goal 14 "Life Below Water" which sets goals for international policy focused on preserving coastal ecosystems and supporting more sustainable economic practices for coastal communities, including in their fishery and aquaculture practices.[3]

Definitions

According to the FAO, "...a fishery is an activity leading to harvesting of fish. It may involve capture of wild fish or raising of fish through aquaculture." It is typically defined in terms of the "people involved, species or type of fish, area of water or seabed, method of fishing, class of boats, purpose of the activities or a combination of the foregoing features".[4]

The definition often includes a combination of fish and fishers in a region, the latter fishing for similar species with similar gear types.[5][6] Some government and private organizations, especially those focusing on recreational fishing include in their definitions not only the fishers, but the fish and habitats upon which the fish depend.

Economic importance

Directly or indirectly, the livelihood of over 500 million people in developing countries depends on fisheries and aquaculture. Overfishing, including the taking of fish beyond sustainable levels, is reducing fish stocks and employment in many world regions.[7][8] A report by Prince Charles' International Sustainability Unit, the New York-based Environmental Defence Fund and 50in10 published in July 2014 estimated global fisheries were adding US$270 billion a year to global GDP, but by full implementation of sustainable fishing, that figure could rise by as much as US$50 billion.[9] In additional to commercial and subsistence fishing, recreational (sport) fishing is popular and economically important in many regions.[10]

The term fish

- In biology – the term fish is most strictly used to describe any animal with a backbone that has gills throughout life and has limbs, if any, in the shape of fins.[11] Many types of aquatic animals commonly referred to as fish are not fish in this strict sense; examples include shellfish, cuttlefish, starfish, crayfish and jellyfish. In earlier times, even biologists did not make a distinction—sixteenth century natural historians classified also seals, whales, amphibians, crocodiles, even hippopotamuses, as well as a host of marine invertebrates, as fish.[12]

- In fisheries – the term fish is used as a collective term, and includes mollusks, crustaceans and any aquatic animal which is harvested.[4]

- True fish – The strict biological definition of a fish, above, is sometimes called a true fish. True fish are also referred to as finfish or fin fish to distinguish them from other aquatic life harvested in fisheries or aquaculture.

Types

Fisheries are harvested for their value (commercial, recreational or subsistence). They can be saltwater or freshwater, wild or farmed. Examples are the salmon fishery of Alaska, the cod fishery off the Lofoten islands, the tuna fishery of the Eastern Pacific, or the shrimp farm fisheries in China. Capture fisheries can be broadly classified as industrial scale, small-scale or artisanal, and recreational.

Close to 90% of the world's fishery catches come from oceans and seas, as opposed to inland waters. These marine catches have remained relatively stable since the mid-nineties (between 80 and 86 million tonnes).[13] Most marine fisheries are based near the coast. This is not only because harvesting from relatively shallow waters is easier than in the open ocean, but also because fish are much more abundant near the coastal shelf, due to the abundance of nutrients available there from coastal upwelling and land runoff. However, productive wild fisheries also exist in open oceans, particularly by seamounts, and inland in lakes and rivers.

Most fisheries are wild fisheries, but farmed fisheries are increasing. Farming can occur in coastal areas, such as with oyster farms,[14] or the aquaculture of salmon, but more typically fish farming occurs inland, in lakes, ponds, tanks and other enclosures.

There are commercial fisheries worldwide for finfish, mollusks, crustaceans and echinoderms, and by extension, aquatic plants such as kelp. However, a very small number of species support the majority of the world's fisheries. Some of these species are herring, cod, anchovy, tuna, flounder, mullet, squid, shrimp, salmon, crab, lobster, oyster and scallops. All except these last four provided a worldwide catch of well over a million tonnes in 1999, with herring and sardines together providing a harvest of over 22 million metric tons in 1999. Many other species are harvested in smaller numbers.

Production

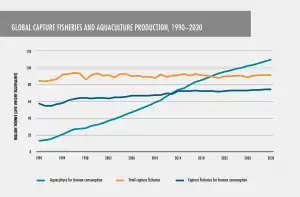

Total fish production in 2016 reached an all-time high of 171 million tonnes, of which 88 percent was utilized for direct human consumption, thanks to relatively stable capture fisheries production, reduced wastage and continued aquaculture growth. This production resulted in a record-high per capita consumption of 20.3 kg in 2016.[15] Since 1961 the annual global growth in fish consumption has been twice as high as population growth. While annual growth of aquaculture has declined in recent years, significant double-digit growth is still recorded in some countries, particularly in Africa and Asia.[15]

FAO predicts the following major trends for the period up to 2030:

- World fish production, consumption and trade are expected to increase, but with a growth rate that will slow over time.[15]

- Despite reduced capture fisheries production in China, world capture fisheries production is projected to increase slightly through increased production in other areas if resources are properly managed. Expanding world aquaculture production, although growing more slowly than in the past, is anticipated to fill the supply–demand gap.[15]

- Prices will all increase in nominal terms while declining in real terms, although remaining high.[15]

- Food fish supply will increase in all regions, while per capita fish consumption is expected to decline in Africa, which raises concerns in terms of food security.[15]

- Trade in fish and fish products is expected to increase more slowly than in the past decade, but the share of fish production that is exported is projected to remain stable.[15]

Management

The goal of Fisheries management is to produce sustainable biological, social, and economic benefits from renewable aquatic resources. Fisheries are classified as renewable because the organisms of interest (e.g., fish, shellfish, reptiles, amphibians, and marine mammals) usually produce an annual biological surplus that with judicious management can be harvested without reducing future productivity.[16] Fisheries management employs activities that protect fishery resources so sustainable exploitation is possible, drawing on fisheries science and possibly including the precautionary principle. Modern fisheries management is often referred to as a governmental system of appropriate management rules based on defined objectives and a mix of management means to implement the rules, which are put in place by a system of monitoring control and surveillance. A popular approach is the ecosystem approach to fisheries management.[17][18] According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), there are "no clear and generally accepted definitions of fisheries management".[19] However, the working definition used by the FAO and much cited elsewhere is:

The integrated process of information gathering, analysis, planning, consultation, decision-making, allocation of resources and formulation and implementation, with enforcement as necessary, of regulations or rules which govern fisheries activities in order to ensure the continued productivity of the resources and the accomplishment of other fisheries objectives.[19]

Law

Fisheries law is an emerging and specialized area of law. Fisheries law is the study and analysis of different fisheries management approaches such as catch shares e.g. Individual Transferable Quotas; TURFs; and others. The study of fisheries law is important in order to craft policy guidelines that maximize sustainability and legal enforcement.[20] This specific legal area is rarely taught at law schools around the world, which leaves a vacuum of advocacy and research. Fisheries law also takes into account international treaties and industry norms in order to analyze fisheries management regulations.[21] In addition, fisheries law includes access to justice for small-scale fisheries and coastal and aboriginal communities and labor issues such as child labor laws, employment law, and family law.[22]

Another important area of research covered in fisheries law is seafood safety. Each country, or region, around the world has a varying degree of seafood safety standards and regulations. These regulations can contain a large diversity of fisheries management schemes including quota or catch share systems. It is important to study seafood safety regulations around the world in order to craft policy guidelines from countries who have implemented effective schemes. Also, this body of research can identify areas of improvement for countries who have not yet been able to master efficient and effective seafood safety regulations.

Fisheries law also includes the study of aquaculture laws and regulations. Aquaculture, also known as aquafarming, is the farming of aquatic organisms, such as fish and aquatic plants. This body of research also encompasses animal feed regulations and requirements. It is important to regulate what feed is consumed by fish in order to prevent risks to human health and safety.Environmental issues

Sustainable harvest

Among the many challenges in fisheries management is the difficulty of reducing the percentage of fish stocks fished beyond biological sustainability.[15]

Climate change

The full relationship between fisheries and climate change is difficult to explore due to the context of each fishery and the many pathways that climate change affects.[24] However, there is strong global evidence for these effects. Rising ocean temperatures[25] and ocean acidification[26] are radically altering marine aquatic ecosystems, while freshwater ecosystems are being impacted by changes in water temperature, water flow, and fish habitat loss.[27] Climate change is modifying fish distribution[28] and the productivity of marine and freshwater species.

The impacts of climate change on ocean systems has impacts on the sustainability of fisheries and aquaculture, on the livelihoods of the communities that depend on fisheries, and on the ability of the oceans to capture and store carbon (biological pump). The effect of sea level rise means that coastal fishing communities are significantly impacted by climate change, while changing rainfall patterns and water use impact on inland freshwater fisheries and aquaculture.See also

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO License statement/permission on Wikimedia Commons. Text taken from In brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018, FAO, FAO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO License statement/permission on Wikimedia Commons. Text taken from In brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018, FAO, FAO.

Notes

- Fletcher, WJ; Chesson, J; Fisher, M; Sainsbury KJ; Hundloe, T; Smith, ADM and Whitworth, B (2002) The "How To" guide for wild capture fisheries. National ESD reporting framework for Australian fisheries: FRDC Project 2000/145. Page 119–120.

- Urbina, Ian (2019). "The Lone Patrol". The Outlaw Ocean. Knopf Doubleday.

- United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- FAO Fishery Glossary; "Fishery" (Entry: 98327). Rome: FAO. 2009. p. 24. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Madden, CJ and Grossman, DH (2004) A Framework for a Coastal/Marine Ecological Classification Standard Archived October 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. NatureServe, page 86. Prepared for NOAA under Contract EA-133C-03-SE-0275

- Blackhart, K; et al. (2006). NOAA Fisheries Glossary: "Fishery" (PDF) (Revised ed.). Silver Spring MD: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 16. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- C. Michael Hogan (2010) Overfishing, Encyclopedia of earth, topic ed. Sidney Draggan, ed. in chief C. Cleveland, National Council on Science and the Environment (NCSE), Washington DC

- Fisheries and Aquaculture in our Changing Climate Policy brief of the FAO for the UNFCCC COP-15 in Copenhagen, December 2009.

- "Prince Charles calls for greater sustainability in fisheries". London Mercury. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Hubert, Wayne; Quist, Michael, eds. (2010). Inland Fisheries Management in North America (Third ed.). Bethesda, MD: American Fisheries Society. p. 736. ISBN 978-1-934874-16-5.

- Nelson, Joseph S. (2006). Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 2. ISBN 0-471-25031-7.

- Jr.Cleveland P Hickman, Larry S. Roberts, Allan L. Larson: Integrated Principles of Zoology, McGraw-Hill Publishing Co, 2001, ISBN 0-07-290961-7

- "Scientific Facts on Fisheries". GreenFacts Website. 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- New Zealand Seafood Industry Council. Mussel Farming.

- In brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018 (PDF). FAO. 2018.

- Lackey, Robert; Nielsen, Larry, eds. (1980). Fisheries management. Blackwell. p. 422. ISBN 978-0632006151.

- Garcia SM, Zerbi A, Aliaume C, Do Chi T, Lasserre G (2003). The ecosystem approach to fisheries. Issues, terminology, principles, institutional foundations, implementation and outlook. FAO.

- FAO (1997) Fisheries Management Section 1.2, Technical Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries. FAO, Rome. ISBN 92-5-103962-3

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Fisheries Service, available at http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/aboutus.htm

- Kevern L. Cochrane, A Fishery Manager’s Guidebook: Management Measures and their Application, Fisheries Technical Paper 424, available at ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/004/y3427e/y3427e00.pdf

- Robert Stewart, Oceanography in the 21st Century – An Online Textbook, Fisheries Issues, available at http://oceanworld.tamu.edu/resources/oceanography-book/fisheriesissues.htm

- Sarwar G.M. (2005). "Impacts of Sea Level Rise on the Coastal Zone of Bangladesh" (PDF). Lund University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

Masters thesis

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Vincent, Warwick; et al. (2006). "Climate Impacts on Arctic Freshwater Ecosystems and Fisheries: Background, Rationale and Approach of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (ACIA)". Ambio. 35 (7): 326–329. doi:10.1579/0044-7447(2006)35[326:CIOAFE]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4315751. PMID 17256636.

- Observations: Oceanic Climate Change and Sea Level Archived 2017-05-13 at the Wayback Machine In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (15MB).

- Doney, S. C. (March 2006). "The Dangers of Ocean Acidification" (PDF). Scientific American. 294 (3): 58–65. Bibcode:2006SciAm.294c..58D. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0306-58. PMID 16502612.

- US EPA, OAR (2015-04-07). "Climate Action Benefits: Freshwater Fish". US EPA. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- Cheung, W.W.L.; et al. (October 2009). "Redistribution of Fish Catch by Climate Change. A Summary of a New Scientific Analysis" (PDF). Pew Ocean Science Series. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

References

- Cullis-Suzuki S and Pauly D (2010) "Failing the high seas: A global evaluation of regional fisheries management organizations" Marine Policy, 34(5) pp 1036–1042.

- FAO: Types of fisheries

- Hart PJB and Reynolds JD (2002) Handbook of fish biology and fisheries Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-632-05412-1

External links

| Look up fishery in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Fisheries. |

- Fisheries at Curlie

- FAO Fisheries Department and its SOFIA report

- The Fishery Resources Monitoring System (FIRMS)

- The International Institute of Fisheries Economics and Trade (IIFET)

- Dynamic Changes in Marine Ecosystems: Fishing, Food Webs, and Future Options (2006), U.S. National Academy of Sciences

- UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project and its Fisheries Refugia Portal and National Reports on Fish Stocks and Habitats in the South China Sea

- World Fisheries Day: Seafood for Thought and World Fisheries from Sea to Table slideshow on the Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- Hawes, J. W. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Fisheries Wiki A detailed online encyclopaedia providing current and quantitative information on marine fisheries worldwide.

.png.webp)