Forestry in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom,[Notes 1] being in the British Isles, is ideal for tree growth, thanks to its mild winters, plentiful rainfall, fertile soil and hill-sheltered topography. Growth rates for broadleaved (hardwood) trees exceed those of mainland Europe, while conifer (softwood) growth rates are three times those of Sweden and five times those of Finland. In the absence of people, much of Great Britain would be covered with mature oaks, except for Scotland. Although conditions for forestry are good, trees do face damage threats arising from fungi, parasites and pests.[1][2]

Nowadays, about 12.9% of Britain's land surface is wooded. The country's supply of timber was severely depleted during the First and Second World Wars, when imports were difficult, and the forested area bottomed out at under 5% of Britain's land surface in 1919. That year, the Forestry Commission was established to produce a strategic reserve of timber. Other European countries average from 25% to 72% (Finland) of their area as woodland.[3][4][5][6][7]

Of the 31,380 square kilometres (12,120 sq mi) of forest in Britain, around 30% is publicly owned and 70% is in the private sector.[Notes 2] More than 40,000 people work on this land. Conifers account for around one half (51%) of the UK woodland area, although this proportion varies from around one quarter (26%) in England to around three quarters (74%) in Scotland.[8] Britain's native tree flora comprises 32 species, of which 29 are broadleaves. Britain's industry and populace uses at least 50 million tonnes of timber a year. More than 75% of this is softwood, and Britain's forests cannot supply the demand; in fact, less than 10% of the timber used in Britain is home-grown. Paper and paper products make up more than half the wood consumed in Britain by volume.[3][9][10][11]

In October 2010, the new coalition government of the UK suggested it might sell off around half the Forestry Commission-owned woodland in the UK. A wide variety of groups were vocal about their disapproval, and by February 2011, the government abandoned the idea. Instead, it set up the Independent Panel on Forestry led by Rt Rev James Jones, then the Bishop of Liverpool. This body published its report in July 2012. Among other suggestions, it recommended that the forested portion of England should rise to 15% of the country's land area by 2060.[7]

Background

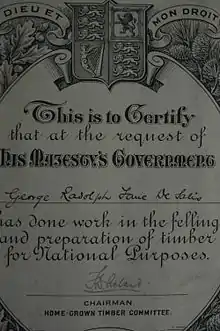

Throughout most of British history, people have most commonly created farmland at the expense of forest. Furthermore, variations in the Holocene climate have led to significant changes in the ranges of many species. This makes it complex to estimate the likely extent of natural forest cover. For example, in Scotland four main areas have been identified: oak dominated forest south of the Highland Line, Scots Pine in the Central Highlands, hazel/oak or pine/birch/oak assemblages in the north-east and south-west Highlands, and birch in the Outer Hebrides, Northern Isles and far north of the mainland. Furthermore, the effects of fire, human clearance and grazing probably limited forest cover to about 50% of the land area of Scotland even at its maximum. The stock of woodland declined alarmingly during the First World War[12] and "a Forestry Subcommittee was added to the Reconstruction Committee to advise on policy when the war was over. The Subcommittee, better known as the Acland Committee after its chairman Sir A. H. D. Acland, came to the conclusion that, in order to secure the double purpose of being able to be independent from foreign supplies for three years and a reasonable insurance against a timber famine, the woods of Great Britain should be gradually increased from three million acres to four and three quarter millions at the end of the war".[13] Following the Acland Report of 1918 the Forestry Commission was formed in 1919 to meet this need. State forest parks were established in 1935.[14][15][16][5]

Emergency felling controls had been introduced in the First and Second World Wars, and these were made permanent in the Forestry Act 1951. Landowners were also given financial incentives to devote land to forests under the Dedication Scheme, which in 1981 became the Forestry Grant Scheme. By the early 1970s, the annual rate of planting exceeded 40,000 hectares (99,000 acres) per annum. Most of this planting comprised fast-growing conifers. Later in the century the balance shifted, with fewer than 20,000 hectares (49,000 acres) per annum being planted during the 1990s, but broadleaf planting actually increased, exceeding 1,000 hectares (2,500 acres) per year in 1987. By the mid-1990s, more than half of new planting was broadleaf.[9][17]

In 1988, the Woodland Grant Scheme replaced the Forestry Grant Scheme, paying nearly twice as much for broadleaf woodland as conifers. (In England, the Woodland Grant Scheme was subsequently replaced by the English Woodland Grant Scheme, which operates six separate kinds of grant for forestry projects.)[19][20] That year, the Farm Woodlands Scheme was also introduced, and replaced by the Farm Woodland Premium Scheme in 1992.[21] In the 1990s, a programme of afforestation resulted in the establishment of Community Forests and the National Forest, which celebrated the planting of its seven millionth tree in 2006.[22] As a result of these initiatives, the British Isles are one of a very few places in the world where the stock of forested land is actually increasing, though the rate of increase has slowed since the turn of the millennium.[23]

England Rural Development Programme is the current overarching grants scheme that includes money for forested land within it.

Ancient woodland

Ancient woodland is defined as any woodland that has been continuously forested since 1600. It is recorded on either the Register of Ancient Semi-Natural Woodland or the Register of Planted Woodland Sites. There is no woodland in Britain that has not been profoundly affected by human intervention. Apart from certain native pinewoods in Scotland, it is predominantly broadleaf. Such woodland is less productive, in terms of timber yield, but ecologically rich, typically containing a number of "indicator species" of indigenous wildlife. It comprises roughly 20% of the forested area.[24][25]

Native and historic tree species

Britain is relatively impoverished in terms of native species. For example, only thirty-one species of deciduous tree and shrub are native to Scotland, including ten willows, four whitebeams and three birch and cherry.[26][Notes 3] This is a list of tree species that existed in Britain before 1900. The sheer number of tree species planted subsequently precludes a complete list.[Notes 4]

Common name Scientific name Period Type Notes Ash Fraxinus excelsior Native Broadleaf - Aspen Populus tremula Native Broadleaf - Atlas cedar Cedrus atlantica 1800–1900 Conifer - Austrian pine Pinus nigra 1800–1900 Conifer - Bay willow Salix pentandra Native Broadleaf - Beech Fagus sylvatica Native Broadleaf - Bird cherry Prunus padus Native Broadleaf - Black cottonwood Populus trichocarpa 1800–1900 Broadleaf - Black poplar Populus nigra Native Broadleaf - Black walnut Juglans nigra 1600–1800 Broadleaf - Box Buxus sempervirens Native Broadleaf - Caucasian fir Abies nordmanniana 1800–1900 Conifer - Cedar of Lebanon Cedrus libani 1600–1800 Conifer - Coast redwood Sequoia sempervirens 1800–1900 Conifer - Common alder Alnus glutinosa Native Broadleaf - Common juniper Juniperus communis Native Conifer - Common lime Tilia x vulgaris 1600–1800 Broadleaf - Common silver fir Abies alba 1600–1800 Conifer - Common walnut Juglans regia pre-1600 Broadleaf - Corsican pine Pinus nigra 1600–1800 Conifer - Crab apple Malus sylvestris Native Broadleaf - Crack willow Salix fragilis Native Broadleaf - Cricket-bat willow Salix alba, var caerulea 1600–1800 Broadleaf - Deodar cedar Cedrus deodara 1800–1900 Conifer - Douglas fir Pseudotsuga menziesii 1800–1900 Conifer Tallest tree in the UK Downy birch Betula pubescens Native Broadleaf May have been the first tree to grow in Britain after the ice age English elm Ulmus procera pre-1600 Broadleaf Despite the name, not a native species Eucalypts Eucalyptus species 1800–1900 Broadleaf - European larch Larix decidua 1600–1800 Conifer - Field maple Acer campestre Native Broadleaf - Giant fir Abies grandis 1800–1900 Conifer - Giant sequoia Sequoiadendron giganteum 1850s– Present Conifer - Found in botanical gardens and private estates Grey alder Alnus glutinosa 1600–1800 Broadleaf - Grey poplar Populus x canescens pre-1600 Broadleaf - Hawthorn Crataegus monogyna Native Broadleaf - Hazel Corylus avellana Native Broadleaf - Holly Ilex aquifolium Native Broadleaf - Holm oak Quercus ilex pre-1600 Broadleaf - Hornbeam Carpinus betulus Native Broadleaf - Horse chestnut Aesculus hippocastanum 1600–1800 Broadleaf - Italian alder Alnus cordata 1800–1900 Broadleaf - Japanese larch Larix kaempferi 1800–1900 Conifer - Large-leaved lime Tilia platyphyllos Native Broadleaf - Lawson cypress Chamaecyparis lawsoniana 1800–1900 Conifer - Lodgepole pine Pinus contorta 1800–1900 Conifer - Lombardy poplar Populus nigra var. italica 1600–1800 Broadleaf - London plane Platanus x hispanica 1600–1800 Broadleaf Maritime pine Pinus pinaster pre-1600 Conifer - Midland thorn Crataegus laevigata Native Broadleaf - Monkey puzzle Araucaria araucana 1600–1800 Conifer - Monterey cypress Cupressus macrocarpa 1800–1900 Conifer - Monterey pine Pinus radiata 1800–1900 Conifer - Noble fir Abies procera 1800–1900 Conifer - Norway maple Acer platanoides 1600–1800 Broadleaf - Norway spruce Picea abies pre-1600 Conifer Supplanted as most common forestry species by Sitka spruce Oriental plane Platanus orientalis pre-1600 Broadleaf - Pedunculate oak Quercus robur Native Broadleaf Also called the English Oak Red alder Alnus rubra 1800–1900 Broadleaf - Red oak Quercus rubra 1600–1800 Broadleaf - Robusta poplar Populus x robusta 1800–1900 Broadleaf - Rowan Sorbus aucuparia Native Broadleaf - Sallow (Goat willow) Salix caprea Native Broadleaf - Scots pine Pinus sylvestris Native Conifer - Serotina poplar Populus x serotina 1600–1800 Broadleaf - Sessile oak Quercus petraea Native Broadleaf - Silver birch Betula pendula Native Broadleaf - Sitka spruce Picea sitchensis 1800–1900 Conifer Most common forestry species Small-leaved lime Tilia cordata Native Broadleaf - Smooth-leaved elm Ulmus carpinifolia pre-1600 Broadleaf - Southern beech Nothofagus antarctica 1800–1900 Broadleaf - Swamp cypress Taxodium distichum 1600–1800 Conifer - Swedish whitebeam Sorbus intermedia pre-1600 Broadleaf - Sweet chestnut Castanea sativa pre-1600 Broadleaf - Sycamore Acer pseudoplatanus pre-1600 Broadleaf - Turkey oak Quercus cerris 1600–1800 Broadleaf - Wellingtonia Sequoiadendron giganteum 1800–1900 Conifer - Western hemlock Tsuga heterophylla 1800–1900 Conifer - Western red cedar Thuja plicata 1800–1900 Conifer - White poplar Populus alba pre-1600 Broadleaf - White willow Salix alba Native Broadleaf - Whitebeam Sorbus aria Native Broadleaf - Wild cherry (Gean) Prunus avium Native Broadleaf - Wild service tree Sorbus torminalis Native Broadleaf - Wych elm Ulmus glabra Native Broadleaf - Yew Taxus baccata Native Conifer -

Threats

Most serious disease threats to British woodland involve fungus. For conifers, the greatest threat is White Rot Fungus (Heterobasidion annosum). Dutch Elm Disease arises from two related species of fungi in the genus Ophiostoma, spread by Elm Bark Beetles and acute oak decline has a bacterial cause. Another fungus, Nectria coccinea, causes Beech bark disease, as does Bulgaria polymorpha. Ash canker results from Nectria galligena or Pseudomonas savastanoi, and most trees are vulnerable to Honey Fungus (Armillaria mellea). The oomycete Phytophthora ramorum (responsible for "Sudden oak death" in the USA) has killed large numbers of Japanese Larch trees in the UK.[27][28][29][30][31][32][33]

Beetles, moths and weevils can also damage trees, but the majority do not cause serious harm. Notable exceptions include the Large Pine Weevil (Hylobius abietis), which can kill young conifers, the Spruce Bark Beetle (Ips typographus) which can kill spruces, and the Cockchafer (Melolontha melolontha) which eats young tree roots and can kill in a dry season. Rabbits, squirrels, voles, field mice, deer, and farm animals can pose a significant threat to trees. Air pollution, acid rain, and wildfire represent the main environmental hazards.[34][35]

Timber industry

In 2013, the UK produced 3,582,000 cubic metres of sawn wood, 3,032,000 cubic metres of wood-based panels and 4,561,000 tonnes of paper and paperboard. The UK does not produce enough timber to satisfy domestic demand, and the country has been a net importer of timber and paper for many years. In 2008 the country imported sawn and other wood to a value of £1,243 million and exported £98 million; imported £832 million of wood-based panels and exported £104 million; and imported paper and paper-based products to a value of £4,273 million and exported £1,590 million. In 2012 approximately 15,000 people were employed in forestry and 26,000 in primary wood production in the country, resulting in a gross value added to the country of £1,936 million. With the ongoing closure of sawmills, the biomass industry is likely to be a key driver for future growth.[3][36][37][38][39][7]

Planting

Successful forestry requires healthy, well-formed trees that are resistant to diseases and parasites. The best wood has a straight, circular stem without a spiral grain or fluting, and small, evenly spaced branches. The chances of achieving these are maximised by planting good-quality seed in the best possible growing environment.[40]

Stewardship and management

The Forestry Commission was established in 1919, in order to address a lack of timber following the First World War: at this point Britain had only 5% of its original forest cover left and the government at that time wanted to create a strategic resource of timber.[41] Since then forest coverage has doubled and the commission's remit expanded to include greater focus on sustainable forest management and maximising public benefits. Woodland creation continues to be an important role of the commission, however, and works closely with government to achieve its goal of 12% forest coverage by 2060,[42] championing initiatives such as The Big Tree Plant and Woodland Carbon Code. Originally, the commission operated across Great Britain, however in 2013 Natural Resources Wales took over responsibility for Forestry in Wales,[43] whilst two new bodies (Forestry and Land Scotland and Scottish Forestry) were established in Scotland on 1 April 2019.[44] The Commission retains responsibility for forestry in England, as well as co-coordinating international forestry policy support and certain plant health functions in respect of trees and forestry across the UK.[45] The Forestry Commission is also the government body responsible for the regulation of private forestry in England; felling is generally illegal without first obtaining a licence from the Commission.[46] The Commission is also responsible for encouraging new private forest growth and development. Part of this role is carried out by providing grants in support of private forests and woodlands.

Natural Resources Wales (Welsh: Cyfoeth Naturiol Cymru) is a Welsh Government sponsored body, for the management of all the natural resources of Wales. It was formed from a merger of the Countryside Council for Wales, Environment Agency Wales, and the Forestry Commission Wales, and also assumes some other roles formerly taken by Welsh Government.[47] Other organisations working in Wales to improve the management of Welsh woodlands and forests include Confor,[48] Coed Cymru[49] and Woodknowledge Wales.[50]

In Scotland, both Forestry and Land Scotland and Scottish Forestry are executive agency of the Scottish Government.[51] The key functions of Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) are to look after the national forest estate, including unforested land within this portfolio, and to produce and supply timber. It is expected to enhance biodiversity, increase public access to the outdoors, encourage tourism and support the rural economy.[52] Scottish Forestry is responsible for regulation, policy and support to landowners, including regulation of FLS.[44][51]

The Forest Stewardship Council, more specifically FSC UK, sets forest management standards for the UK, promotes the system and provides an information service. It looks at the environmental, social and economic impacts of the timber industry.

Transportation

Currently, the vast majority of Britain's timber uses road haulage. As forests are located in rural areas, the heavy timber vehicles have severely damaged many single lane tracks, especially in the Highlands. In order to combat this, companies are being forced to provide funding for repairs, as well as using alternative transport systems such as rail and coastal shipping. Despite the number of forest railways plummeting after the Beeching Axe, rail's share of timber transport has risen from 3% in 2002 with the opening of new lines in Devon, the Pennines, Scotland and South Wales by Colas Rail.[53][54][55][56]

Land values

The price of woodland has risen out of proportion to its productivity, and in 2012 reached peak prices over £10,000 per acre. Woodland prices are affected by its very favourable tax treatment and its high amenity value.[7]

See also

References

- Footnotes

- The United Kingdom (sometimes abbreviated to UK) is a political unit (specifically a country), the British Isles is a geographical unit (the archipelago lying off the northwest coast of Europe), and Great Britain is the name of the largest of those islands. In this article "Great Britain" is sometimes abbreviated to "Britain". The adjective "British" can mean either the political or the geographical entity.

- In fact, this is not easy to establish. There is no complete register of who owns land in the United Kingdom. (Nix et al. 1999, p. 2.) HM Land Registry records purchases by way of conveyance, but where land has not changed hands since the Land Registry was established in 1862, no records exist. Two attempts have been made to take a complete census of ownership (the Domesday Book in 1086 and a census in 1873) but both contain significant omissions and are extremely dated besides; and much of the forested land is on long-established estates where ownership is not recorded on any register that can be examined. Often-quoted figures for England come from the Forestry Commission, National Inventory of Woodland and Trees (1998), which claims the breakdown is as follows: Private: Personal: 47.1% Business (including pension funds) 14.3% Public: Forestry Commission 21.8% Other central government: 2.7% Local authority 6% Charity 6.7% Forestry or timber business 0.7%

- This source includes the following shrubs and small trees that do not appear in Hart 1994 and Sterry and Press 1995: Betula nana, Prunus spinosa, Rosa canina, Salix cinerea, Salix aurita, Salix lanata, Salix lapponum (Downy willow), Salix phylicifolia, Salix arbuscala (Mountain willow), Salix myrsinites (Whortle-leaved willow), Salix myrsinifolia, Salix reticulata, Sambucus nigra, Viburnum opulus. Smout et al. 2007 also lists the Arran Whitebeams: Sorbus rupicola (Rock Whitebeam), Sorbus pseudofennica and Sorbus arranensis although not the very rare and recently discovered Sorbus pseudomeinichii

- All the information in the table that follows is adapted from Hart 1994, pp. 12–13, and Sterry & Press 1995.

- Citations

- Hart 1994, p. 68.

- Fitter 2002, p. 10.

- Forestry Facts and Figures 2014: A Summary of Statistics about Woodland and Forestry in the UK (PDF). Forestry Commission. 2014-01-01. ISBN 9780855389147.

- Nix et al. 1999, p. 2.

- Nix et al. 1999, p. 93.

- Hart 1994, p. 321.

- Rural Focus: Forestry Policy, Estates Gazette, 28 July 2012, pages 56-57.

- "Forestry Statistics 2019, Chapter 1 - Woodland area and planting". Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Nix et al. 1999, p. 94.

- Hart 1994, p. 1.

- Hart 1994, p. 13.

- see e.g. The Brecon & Radnor Express June 13, 1918 for local concerns

- Jan Willem Oesthook, The Logic of British Forest Policy, 1919-1970

- Smout et al. 2007, pp. 26–28.

- Tivy, Joy "The Bio-climate" in Clapperton 1983, pp. 90–91.

- Hart 1991, p. 9.

- Nix et al. 1999, p. 95.

- Government Forestry and Woodlands Policy Statement, January 2013.http://www.defra.gov.uk/publications/2013/01/31/pb13871-forestry-policy-statement/

- Nix et al. 1999, p. 98.

- "English Woodland Grant Scheme". Forestry Commission. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Nix et al. 1999, p. 99.

- "Surprise, surprise! It's the National Forest's seven millionth tree!". WebArchive.org. National Forest. 24 November 2006. Archived from the original on 13 February 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Milmo, Cahal (11 June 2010). "'Worrying' slump in tree planting prompts fears of deforestation". The Independent. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Angus (27 June 2008). "What is Ancient Woodland?". woodlands.co.uk. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Hart 1994, p. 146.

- Smout et al. 2007, p. 2.

- "Phytophthora ramorum". Forestry Commission. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Kinver, Mark (28 April 2010). "Oak disease 'threatens landscape'". BBC News. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Hart 1994, p. 229.

- "Dutch elm disease in Britain". forestresearch.gov.uk. Forestry Commission. 24 November 2006. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Hart 1994, p. 230.

- James 1966, p. 142.

- James 1966, p. 143.

- James 1966, p. 158

- Hibbert 1991, p. 99.

- Forestry Commission 2009, table 9.

- Forestry Commission 2009, table 7.

- Forestry Commission 2009, table 12.

- Forestry Commission 2009, table 13.

- Hart 1994, p. 57

- "History of the Forestry Commission". The Forestry Commission. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- "Government Forestry and Woodlands" (PDF). Defra. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Welsh Government-Natural Resources Wales". 9 April 2013.

- "Forestry Commission Scotland and Forest Enterprise Scotland no longer exist". Scottish Government. 4 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "Forestry devolution: resource list". Scottish Government. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- "Felling Licences". Forestry Commission. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- "Welsh Government - Natural Resources Wales". wales.gov.uk. 9 April 2013. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- "Confederation of Forest Industries", Wikipedia, 2018-05-18, retrieved 2019-01-27

- "Coed Cymru".

- "Woodknowledge Wales". Archived from the original on 2017-10-15. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- "Report setting out the administrative arrangements that the Scottish Ministers intend to make for the carrying out of their functions under the Forestry and Land Management (Scotland) Act 2018". March 2019. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "About Us". Forestry and Land Scotland. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Choreley, Stephen (6 Jun 2000). "EXTRAORDINARY DAMAGE TO THE ROAD NETWORK CAUSED BY TIMBER VEHICLES" (PDF). east-ayrshire.gov.uk. EAST AYRSHIRE COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT SERVICES COMMITTEE. Retrieved 27 Jul 2015.

- Högnäs, Tore; Spaven, David (23 Aug 2002). "MORE TIMBER BY RAIL – A CASE FROM FINLAND" (PDF). www.timbertransportforum.org.uk. The Timber Transport Forum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- "Traffic". Railfan's Traffic Guide. North Wales Coast Railway. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- "Crianlarich timber railhead: feasibility study Final Report to Forestry Commission Scotland" (PDF). timbertransportforum.org.uk/. January 2012. Retrieved 22 Jul 2015.

- Bibliography

- Clapperton, Chalmers M. (1983). Scotland: A New Study. Newton Abbott: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8084-2.

- Fitter, A. (2002) [1980]. Trees. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-711074-X.

- Forestry Commission (2009). Forestry Facts and Figures 2009 (PDF). Forestry Commission. ISBN 978-0-85538-790-7.

- Hart, C (1994) [1991]. Practical Forestry for the Agent and Surveyor. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-86299-962-6.

- Hibberd, B. G. (1991). Forestry Practice (11th ed.). Forestry Commission. ISBN 0-11-710281-4.

- James, N. D. G. (1966) [1955]. The Forester's Companion (2nd ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwood.

- Nix; Hill; Williams; Bough (1999) [1987]. Land and Estate Management (3rd ed.). Packard Publishing. ISBN 1-85341-111-6.

- Smout, T. C.; MacDonald, R.; Watson, Fiona (2007). A History of the Native Woodlands of Scotland 1500–1920. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3294-7.

- Sterry, P.; Press, B. (1995). A Photographic Guide to Trees of Britain and Europe. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 1-85368-416-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Forestry in the United Kingdom. |