Gothic secular and domestic architecture

Gothic architecture is a style of architecture that flourished during the high and late medieval period. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture.

Originating in 12th-century France and lasting into the 16th century, Gothic architecture is most familiar as the architecture of many of the great cathedrals, abbeys and churches of Europe. It is also the architecture of many non-religious buildings, such as castles, palaces, town halls, guild halls, universities and to a less prominent extent, private dwellings.

Although secular and civic architecture in general was subordinate in importance to ecclesiastical architecture, civic architecture grew in importance as the Middle Ages progressed. David Watkin, for example writes about secular Gothic architecture in present-day Belgium: "However, it is the secular architecture, the guild-halls and town halls of her prosperous commercial cities, which make Belgium unique. Their splendour often exceeds that of contemporary ecclesiastical foundations, while their decorative language was not without influence on churches such as Antwerp Cathedral."[2] Another exception was Venetian Gothic architecture, which is at its most distinctive in the many surviving palace facades.

Background

Political

At the end of the 12th century, Europe was divided into a multitude of city states and kingdoms. The area encompassing modern Germany, southern Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia, Czech Republic and much of northern Italy (excluding Venice and Papal State) was nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire, but local rulers exercised considerable autonomy. France, Denmark, Poland, Hungary, Portugal, Scotland, Castile, Aragon, Navarre, Sicily and Cyprus were independent kingdoms, as was the Angevin Empire, whose Plantagenet kings ruled England and large domains in what was to become modern France.[3] Norway came under the influence of England, while the other Scandinavian countries, the Baltic States and Poland were influenced by trading contacts with the Hanseatic League. Angevin kings brought the Gothic tradition from France to Southern Italy, while Lusignan kings introduced French Gothic architecture to Cyprus.

Throughout Europe at this time there was a rapid growth in trade and an associated growth in towns.[4][5] Germany and the Lowlands had large flourishing towns that grew in comparative peace, in trade and competition with each other, or united for mutual weal, as in the Hanseatic League. Civic building was of great importance to these towns as a sign of wealth and pride. England and France remained largely feudal and produced grand domestic architecture for their kings, dukes and bishops, rather than grand town halls for their burghers.

.jpg.webp)

Religious

The Catholic Church prevailed across Europe at this time, influencing not only faith but also wealth and power. Bishops were appointed by the Church and often ruled as virtual princes over large estates. The early Medieval periods had seen a rapid growth in monasticism, with several different orders being prevalent and spreading their influence widely. Foremost were the Benedictines whose monastic establishments vastly outnumbered any others in England. A part of their influence was that they tended to build within towns. The Cluniac and Cistercian Orders were prevalent in France, the great monastery at Cluny having established a formula for a well planned monastic site which was then to influence all subsequent monastic building, including domestic quarters, for many centuries.[4][5]

Geographic

From the 10th to the 13th century, Romanesque architecture had become a pan-European style and manner of construction, affecting buildings in countries as far apart as Ireland, Croatia, Sweden and Sicily. The same wide geographic area was then affected by the development of Gothic architecture, but the acceptance of the Gothic style and methods of construction differed from place to place, as did the expressions of Gothic taste. The proximity of some regions meant that modern country borders do not define divisions of style. On the other hand, some regions such as England and Spain produced defining characteristics rarely seen elsewhere, except where they have been carried by itinerant craftsmen, or the transfer of bishops. Regional differences that are apparent in the Romanesque period often become even more apparent in the Gothic.

The local availability of materials affected both construction and style. In France, limestone was readily available in several grades, the very fine white limestone of Caen being favoured for sculptural decoration. England had coarse limestone and red sandstone as well as dark green Purbeck marble which was often used for architectural features.

In Northern Germany, Netherlands, northern Poland, Denmark, and the Baltic countries local building stone was unavailable but there was a strong tradition of building in brick. The resultant style, Brick Gothic, is called "Backsteingotik" in Germany and Scandinavia and is associated with the Hanseatic League. In Italy, stone was used for fortifications, but brick was preferred for other buildings. Because of the extensive and varied deposits of marble, many buildings were faced in marble, or were left with undecorated façade so that this might be achieved at a later date.

The availability of timber also influenced the style of architecture, with timber buildings prevailing in Scandinavia. Availability of timber affected methods of roof construction across Europe. It is thought that the magnificent hammer-beam roofs of England were devised as a direct response to the lack of long straight seasoned timber by the end of the Medieval period, when forests had been decimated not only for the construction of vast roofs but also for ship building.[4][7]

Scope

New cities, town planning and urbanisation

Several new towns and cities were established in Europe during the high and late Middle Ages. Beginning in the 12th century, urbanisation slowly again started to spread across Europe, where urban development had since the fall of the Roman Empire in general been brought to a standstill or of very limited scope. With time, as cities grew and new towns were established, this spurred a political development that slowly began to challenge the feudal system dominant at the time. The growing power of the cities was reflected in the erection of town halls, guilds, and other mercantile and civic buildings.[2] As noted above, regional differences in the structure of political power is reflected in the architecture of medieval cities.

While most cities during the Gothic era grew over a longer period in a more or less haphazard way, there are some examples of centralised town planning from the period. Several new towns designed with grid plans were founded in the south of France in the 13th and 14th centuries, where they are known as Bastides.[9] These cities and towns had their own characteristics: "Purpose-built on unoccupied land, these bastides were immediately different from older medieval villages with winding streets that grew willy-nilly over decades. The bastides adopted the regular square grid of ancient Roman towns, with an arcaded market square at the center. In most cases, the church was set off to the side of the square, pointing to the priority given to trade."[10] The city of Aigues Mortes in southern France is an unusually large example of a consciously redesigned, if not strictly new, city.

In England, a symmetrical plan was conceived but never completely carried out for New Winchelsea, one of the so-called Cinque Ports, wine trading posts in Kent and Sussex.[2] England is also the site of what is claimed to be the oldest purely residential street with its original buildings all surviving intact in Europe, Vicar's Close in Wells, Somerset, a planned street dating from the 1360s.[11] In Wales, Edward I commissioned a series of castles and adjacent new towns as part of a settlement policy with the intent to pacify the recently conquered principality of Wales. Caernarfon and Conwy are two such planned towns of regular layout.[12]

- Town planning

The medieval street layout of Aigues-Mortes, France, developed into a crusader port during the 13th century.

The medieval street layout of Aigues-Mortes, France, developed into a crusader port during the 13th century. Plan of Caernarfon, Wales from 1610, showing the castral town established in Wales to "illustrate in a more symbolic than strategic fashion English power."[12]

Plan of Caernarfon, Wales from 1610, showing the castral town established in Wales to "illustrate in a more symbolic than strategic fashion English power."[12]

.jpg.webp)

It was not only new, founded cities that had extensive building regulations. London, Florence, Paris, Venice and numerous smaller cities in Spain and Italy had rules concerning not only the height and shape of buildings, but also for example regulating the width of streets, the projection of roofs and rules concerning waste management, drainage and fire regulations. The Piazza del Campo in Siena, Italy is one of the earliest examples of "coherent town planning along aesthetic lines, perhaps for the first time since antiquity."[2] Official regulations governing the size of the palaces facing the square date from 1298. The famous square is dominated by the Palazzo Pubblico, the town hall. With growing prosperity and an emerging sense of civic pride, town halls such as Palazzo Pubblico often became a show-piece of the cities' growing confidence. In the cities of northern Italy, this development started early and many Gothic town halls and other civic monuments have to a large extent survived to this day.[2]

Outside of Italy, there was a strong growth of trade not least in the Low Countries, and along the Rhine and Rhône rivers. Present-day Belgium is justly famous for its well-preserved medieval cities, like Bruges and Ghent, and its rich heritage of some of the finest civic Gothic architecture, such as the stupendous town halls of Mons, Ghent, Leuven and Oudenaarde.[2]

Lübeck, founded in 1143, quickly established itself as the centre of the Hanseatic League, and the source of inspiration for cities established and expanded in the Baltic Sea region as trade routes in the area grew in importance. The example of Lübeck influenced and promoted similar architectural development in many of the cities in the area, albeit of course with local variations. Notable examples of such Hanseatic towns with rich medieval heritage include Visby,[14] Tallinn,[15] Toruń,[16] Stralsund and Wismar[17] to name a few. Characteristic for many of these towns is the extensive use of brick, in the so-called Brick Gothic style.[2]

- Civic pride: town halls

Oudenaarde Town Hall built by Hendrik van Pede in 1526-1537 as one of the last Gothic town halls of present-day Belgium.

Oudenaarde Town Hall built by Hendrik van Pede in 1526-1537 as one of the last Gothic town halls of present-day Belgium. Tallinn Town Hall (completed 1404). Hanseatic towns such as Tallinn demonstrated their independence through large town halls.

Tallinn Town Hall (completed 1404). Hanseatic towns such as Tallinn demonstrated their independence through large town halls. The fortress-like Palazzo Vecchio (begun 1299) in Florence.

The fortress-like Palazzo Vecchio (begun 1299) in Florence. Old Town Hall in Toruń, begun in 1259, built mainly in 14th century, housed originally not only city council, but had also commercial, juiridical and representative function

Old Town Hall in Toruń, begun in 1259, built mainly in 14th century, housed originally not only city council, but had also commercial, juiridical and representative function

Castles, fortresses and military structures

Few countries in Europe can rival Spain when it comes to the number of well-preserved Gothic castles, primarily dating from the 15th century. Typical examples of these often severe-looking, strictly military structures are Torrelobatón, El Barco de Ávila and Montealegre castles. An atypical but inventive piece of Gothic architecture is the completely round Bellver Castle on Mallorca island, built in 1300-14 for James II of Majorca by architect Pere Salvà.[2]

In France, the late medieval period — especially the time of the Hundred Years' War — saw the construction of a large number of new, feudal castles and walled towns. Typically, French castles from this time were centred on an either circular or polygonal keep. Examples include the castles at Gisors and Provins.[2]

In parts of what is today Poland and the Baltic States, the crusading Teutonic Knights erected castles, so-called Ordensburgen in recently conquered areas. The crusading order's former headquarters at Malbork (German: Marienburg) castle in Poland is, together with the Papal palace in Avignon, one of the greatest secular buildings of the Middle Ages.[2] Other examples include Kwidzyn (Poland) and Turaida (Latvia).

Many towns and cities in Europe during this time were protected by more or less extensive town walls. Notable examples of still extant Gothic town walls still surround the historical centres of Carcassonne, France, Tallinn, Estonia and York, England.

Universities and schools

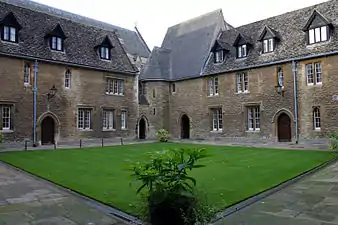

The colleges of Oxford and Cambridge universities in England comprise an outstanding example of English Gothic architecture. The source of inspiration for these English colleges is not the architecture of monasteries, but rather 14th and 15th century manor houses.[2] The structure of the colleges originally developed haphazardly but New College, Oxford, founded in 1379, from the beginning received a planned structure centred on a quadrangle and a cloister. The architectural ensemble incorporated a hall, a chapel, a library and accommodation, and was designed by William Wynford. The concept was further developed at Queens' College, Cambridge in the 1440s, probably designed by Reginald Ely.[2] An example of a college inspired by monastic architecture can be found in Paris, in the College des Bernardins[18] Formerly part of Paris University, this building, ordered in 1245 by the abbot Stephen of Lexington, draws upon Cistercian architecture.

- Universities

Collegium Maius in Kraków, Poland. An example of late Gothic brick architecture. Professors lived and worked upstairs, while lectures were held downstairs.

Collegium Maius in Kraków, Poland. An example of late Gothic brick architecture. Professors lived and worked upstairs, while lectures were held downstairs. The Mob Quad at Merton College, Oxford in England is one of the oldest university quadrangles of Oxford. The pattern has since been copied at many other colleges and universities worldwide.

The Mob Quad at Merton College, Oxford in England is one of the oldest university quadrangles of Oxford. The pattern has since been copied at many other colleges and universities worldwide. Patio de las Escuelas Menores, University of Salamanca, Spain, begun in 1428.

Patio de las Escuelas Menores, University of Salamanca, Spain, begun in 1428.

Hospitals and almshouses

The organisation and practices of the hospital-system in Medieval Europe evolved from Christian monasticism. But the Middle Ages saw the development of both purpose-built, sometimes specialised hospitals and almshouses, conceived to provide housing for the elderly or long-term ill. In the 13th century, urban communities gradually took over the responsibility of caring for the sick.[19] Concerning the architecture of such purpose-built hospitals, at least in England "the basic layout of larger, purpose-built hospitals was quite consistent. A large 'infirmary hall' with rows of beds on each side housed the sick and the infirm. The chapel was in full view - the care of the soul was just as important as the care of the body."[20] Notable examples of almshouses include the Hôtel Dieu in Beaune, France, the Hospital of St Cross in Winchester, England and the Hospital of the Holy Spirit in Lübeck, Germany.

- Hospitals and almshouses

.jpg.webp) The Hospital of the Holy Spirit, Lübeck.

The Hospital of the Holy Spirit, Lübeck. Interior view of the Hôtel Dieu, Beaune.

Interior view of the Hôtel Dieu, Beaune. The Hospital of St Cross is England's oldest and largest almshouse.

The Hospital of St Cross is England's oldest and largest almshouse.

Bridges

Among the most impressive feats of medieval engineering is bridge construction, "comparable with the great cathedrals of the period".[21] Bridges from this period are characterised by typically Gothic ogival arches. It was not uncommon for such bridges to also provide room for shops, chapels and other structures.[22] This can still be seen at the Ponte Vecchio, Florence (Italy). Other fine examples of still extant medieval bridges are the Pont Saint-Bénezet or Pont d'Avignon, Pont Valentré and Pont d'Orthez, all in France, as well as the famous Charles Bridge, Prague (Czech Republic).

.jpg.webp)

- Bridges

Pont Saint-Bénezet, Avignon

Pont Saint-Bénezet, Avignon Ponte Vecchio, Florence

Ponte Vecchio, Florence

Houses and palaces

Purely residential and even palatial buildings also survive in several French cities. The Palais des Papes, the residence of the Pope during the Avignon Papacy, is one of the largest and most important Gothic buildings in Europe.[2] The partially preserved Conciergerie in Paris, formerly a royal palace, is a less intact example of medieval palatial architecture in France. The house of Jacques Coeur in Bourges and the Hôtel de Cluny in Paris are examples of lesser (not royal or papal) but still luxurious, urban residences from the late medieval period.[2]

At the very end of the Gothic period, Benedikt Rejt in Bohemia (present-day Czech Republic), drawing on a local tradition of elaborate tracery and inventiveness (so-called Sondergotik) best represented by Peter Parler, created some of the most elaborate examples of complex vaulting in Gothic architecture at Prague Castle. The Vladislav Hall (built 1493-1502) by Rejt is the largest secular hall of the late Middle Ages.[2] Here and in the so-called "Riders' Staircase" (also in Prague Castle), Rejt devised unique vaults: "[The Vladislav Hall's] amazing vault boasts intertwined double-curved or three-dimensional lierne ribs reaching almost to the floor. Similarly inventive is the vault over the Riders' Staircase with its twisting, asymmetrical, truncated ribs."[2]

The castle of Olite in Navarre, Spain was originally built as a defensive castle but later redesigned into a purely residential palace for the kings of Navarre. It was equipped with such luxuries as a rooftop garden, an aviary, a pool and a lion's den.[2]

Other structures and buildings

A number of medieval shipyards, notably the Drassanes[23] in Barcelona, Spain and the Venetian Arsenal in Venice, Italy survive to this day. Of these two, the Drassanes is the most purely Gothic building complex, while the Venetian arsenal was arguably the most important — indeed, it was the largest industrial complex in Europe prior to the Industrial Revolution.

References

- Gajdošová, Jana (2019). "Holy Roman Empire (Central and Eastern Europe), 1075–1450". In Fraser, Murray (ed.). Sir Banister Fletcher’s Global History of Architecture. I (21st ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. pp. 928–941. doi:10.5040/9781474207768.046. ISBN 978-1-4742-0776-8.

- Watkin, David (2005). A History of Western Architecture (4 ed.). New York: Watson Guptill. ISBN 0-8230-2277-3.

- "L'art Gothique", section: "L'architecture Gothique en Angleterre" by Ute Engel: L'Angleterre fut l'une des premieres régions à adopter, dans la deuxième moitié du XIIeme siècle, la nouvelle architecture gothique née en France. Les relations historiques entre les deux pays jouèrent un rôle prépondérant: en 1154, Henri II (1154–1189), de la dynastie Française des Plantagenêt, accéda au thrône d'Angleterre." (England was one of the first regions to adopt, during the first half of the 12th century, the new Gothic architecture born in France. Historic relationships between the two countries played a determining role: in 1154, Henry II (1154–1189) became the first of the Anjou Plantagenet kings to ascend to the throne of England).

- Banister Fletcher, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method.

- John Harvey, The Gothic World

- Correia, Jorge; González Tornel, Pablo (2019). "Spain and Portugal, 1200–1492". In Fraser, Murray (ed.). Sir Banister Fletcher’s Global History of Architecture. I (21st ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. pp. 978–992. doi:10.5040/9781474207768.048. ISBN 978-1-4742-0776-8.

- Alec Clifton-Taylor, The Cathedrals of England

- Historic England. "Guildhall and Chamber Range, Atkinson block, Common Hall Lane and boundary wall containing entrance to lane (1257929)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "The fortified towns of Aquitaine". Tourisme Aquitaine. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- Vallois, Thirza (16 March 2011). "Intriguing Bastides". France Today. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "Vicars' Close, Wells". Wells Visitor Service. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- den Hartog, Elizabeth (2019). "The Low Countries, 1000–1430". In Fraser, Murray (ed.). Sir Banister Fletcher’s Global History of Architecture. I (21st ed.). London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. pp. 993–1002. doi:10.5040/9781474207768.049. ISBN 978-1-4742-0776-8.

- "Hanseatic Town of Visby". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "Historic Centre (Old Town) of Tallinn". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "Medieval Town of Toruń". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "Historic Centres of Stralsund and Wismar". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- http://www.collegedesbernardins.fr/fr/le-college/histoire.html

- Buklijaš, Tatjana (April 2008). "Medicine and Society in the Medieval Hospital". Croatian Medical Journal. 49 (2): 151–154. doi:10.3325/cmj.2008.2.151. PMC 2359880.

- "Disability in Medieval Hospitals and Almshouses". English Heritage. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- Harrison, David. "The Bridges of Medieval England: Transport and Society 400-1800". Oxford Scholarship Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- Shirley-Smith, Hubert. "Bridge (engineering)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- "Civil gothic architecture". Generalitat de Catalunya. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2013.