Angevin Empire

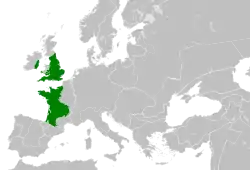

The Angevin Empire (/ˈændʒɪvɪn/; French: Empire Plantagenêt) describes the possessions of the Angevin kings of England who held lands in England and France during the 12th and 13th centuries. Its rulers were Henry II (ruled 1154–1189), Richard I (r. 1189–1199), and John (r. 1199–1216). The Angevin Empire is an early example of a composite state.[2]

Angevin Empire | |

|---|---|

| 1154–1214 | |

Royal banner (first used after 1198)

Royal coat of arms

| |

The extent of the Angevin Empire around 1190 | |

| Status | Personal union, empire |

| Capital | No official capital. Court was generally held at Angers and Chinon. |

| Common languages | Old French, Latin, Norman French, Anglo-Norman, Middle English, Gascon, Basque, Middle Welsh, Breton, Cornish, Middle Irish, Cumbric, Zarphatic |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (official) |

| Government | Feudal monarchy |

| Emperor, King, Prince, Duke, Count and Lord | |

• 1154–1189 | Henry II |

• 1189–1199 | Richard I |

• 1199–1216 (effective end of the Angevin Empire in 1214) | John |

• 1216–1259 (de jure rule) | Henry III |

| Historical era | Middle Ages |

| 25 October 1154 | |

| 27 July 1214 | |

| 4 December 1259 | |

| Currency | French livre, silver penny, gold penny |

| Today part of |

|

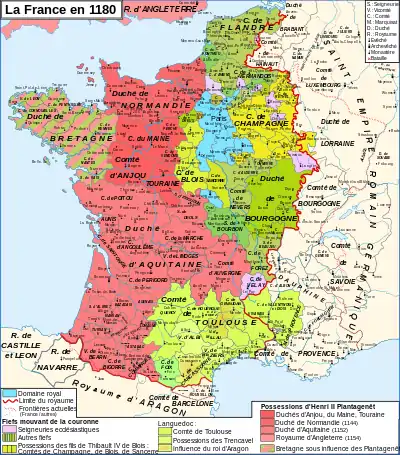

The Angevins of the House of Plantagenet ruled over an area covering roughly half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and Wales, and had further influence over much of the remaining British Isles. The empire was established by Henry II, as King of England, Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou (from which the Angevins derive their name), as well as Duke of Aquitaine by right of his wife, and multiple subsidiary titles. Although their title of highest rank came from the Kingdom of England, the Angevins held court primarily on the continent at Angers in Anjou, and Chinon in Touraine.

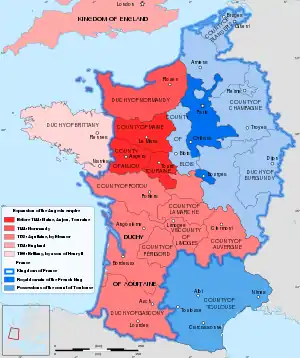

The influence and power of the House of Anjou brought them into conflict with the kings of France of the House of Capet, to whom they also owed feudal homage for their French possessions, bringing in a period of rivalry between the dynasties. Despite the extent of Angevin rule, Henry's son, John, was defeated in the Anglo-French War (1213–1214) by Philip II of France following the Battle of Bouvines. John lost control of most of his continental possessions, apart from Gascony in southern Aquitaine. This defeat set the scene for further conflicts between England and France, leading up to the Hundred Years' War.

Origin of the term and its application

The term Angevin Empire is a neologism defining the lands of the House of Plantagenet: Henry II and his sons Richard I and John. Another son, Geoffrey, ruled Brittany and established a separate line there. As far as historians know, there was no contemporary term for the region under Angevin control; however, descriptions such as "our kingdom and everything subject to our rule whatever it may be" were used.[3] The term Angevin Empire was coined by Kate Norgate in her 1887 publication, England under the Angevin Kings.[4] In France, the term espace Plantagenet (French for "Plantagenet area") is sometimes used to describe the fiefdoms the Plantagenets had acquired.[5]

The adoption of the Angevin Empire label marked a re-evaluation of the times, considering that both English and French influence spread throughout the dominion in the half century during which the union lasted. The term Angevin itself is the demonym for the residents of Anjou and its historic capital, Angers; the Plantagenets were descended from Geoffrey I, Count of Anjou, hence the term.[6] The demonym, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, has been in use since 1653.[6]

The use of the term Empire has engendered controversy among some historians over whether the term is accurate for the actual state of affairs at the time. The area was a collection of the lands inherited and acquired by Henry, and so it is unclear whether these dominions shared any common identity and so should be labelled with the term Empire.[7][8][9] Some historians argue that the term should be reserved solely for the Holy Roman Empire, the only Western European political structure actually named an empire at that time,[10] although Alfonso VII of León and Castile had taken the title "Emperor of all Spain" in 1135.[11] Other historians argue that Henry II's empire was neither powerful, centralised, nor large enough to be seriously called an empire.[10] Furthermore, the Plantagenets never claimed any sort of imperial title as implied by the term Angevin Empire.[12] However, even if the Plantagenets themselves did not claim an imperial title, some chroniclers, often working for Henry II himself, did use the term empire to describe this assemblage of lands.[10] The highest title was "king of England"; the other titles of dukes and counts of different areas held in France were completely and totally independent from the royal title, and not subject to any English royal law.[13] Because of this, some historians prefer the term commonwealth to empire, emphasising that the Angevin Empire was more of an assemblage of seven fully independent, sovereign states loosely bound to each other, only united in the person of the king of England.[14]

Geography and administration

At its largest extent, the Angevin Empire consisted of the Kingdom of England, the Lordship of Ireland, the duchies of Normandy (which included the Channel Islands), Gascony and Aquitaine[15] as well as of the counties of Anjou, Poitou, Maine, Touraine, Saintonge, La Marche, Périgord, Limousin, Nantes and Quercy. While the duchies and counties were held with various levels of vassalage to the king of France,[16] the Plantagenets held various levels of control over the Duchies of Brittany and Cornwall, the Welsh princedoms, the county of Toulouse, and the Kingdom of Scotland, although those regions were not formal parts of the empire. Auvergne was also in the empire for part of the reigns of Henry II and Richard, in their capacity as dukes of Aquitaine. Henry II and Richard I pushed further claims over the County of Berry but these were not completely fulfilled and the county was lost completely by the time of the accession of John in 1199.

The frontiers of the empire were sometimes well known and therefore easy to mark, such as the dykes constructed between the royal demesne of the king of France and the Duchy of Normandy. In other places these borders were not so clear, particularly the eastern border of Aquitaine, where there was often a difference between the frontier Henry II, and later Richard I, claimed, and the frontier where their effective power ended.[17]

Scotland was an independent kingdom, but after a disastrous campaign led by William the Lion, English garrisons were established in the castles of Edinburgh, Roxburgh, Jedburgh and Berwick in southern Scotland as defined in the Treaty of Falaise.[18]

Administration and government

One characteristic of the Angevin Empire was its "polycratic" nature, a term taken from a political pamphlet written by a subject of the Angevin Empire: the Policraticus by John of Salisbury. This meant that, rather than the empire being controlled fully by the ruling monarch, he would delegate power to specially appointed subjects in different areas.

Britain

England was under the firmest control of all the lands in the Angevin Empire, due to the age of many of the offices that governed the country and the traditions and customs that were in place. England was divided in shires with sheriffs in each enforcing the common law. A justiciar was appointed by the king to stand in his absence when he was on the continent. As the kings of England were more often in France than England they used writs more frequently than the Anglo-Saxon kings, which actually proved beneficial to England.[19] Under William I's rule, Anglo-Saxon nobles had been largely replaced by Anglo-Norman ones who couldn't own large expanses of contiguous lands, because their lands were split between England and France. This made it much harder for them to revolt against the king and defend all of their lands at once. Earls held a status similar to that of the continental counts, but there were no dukes at this time, only ducal titles that the kings of England held.

Wales obtained good terms provided it paid homage to the Plantagenets and recognised them as lords.[20] However, it remained almost self-ruling. It supplied the Plantagenets with infantry and longbowmen.

Ireland

Ireland was ruled by the Lord of Ireland who had a hard time imposing his rule at first. Dublin and Leinster were Angevin strongholds while Cork, Limerick and parts of eastern Ulster were taken by Anglo-Norman nobles.[21]

France

All the continental domains that the Angevin kings ruled were governed by a seneschal at the top of the hierarchical system, with lesser government officials such as baillis, vicomtes, and prévôts.[22] However, all counties and duchies would differ to an extent.

Greater Anjou is a modern term to describe the area consisting of Anjou, Maine, Touraine, Vendôme, and Saintonge.[23] Here, prévôts, the seneschal of Anjou, and other seneschals governed. They were based at Tours, Chinon, Baugé, Beaufort, Brissac, Angers, Saumur, Loudun, Loches, Langeais and Montbazon. However, the constituent counties, such as Maine, were often administered by the officials of the local lords, rather than their Angevin suzerains. Maine was at first largely self-ruling and lacked administration until the Angevin kings made efforts to improve administration by installing new officials, such as the seneschal of Le Mans. These reforms came too late for the Angevins however, and only the Capetians saw the beneficial effects of this reform after they annexed the area.[24]

Aquitaine differed in the level of administration in its different constituent regions. Gascony was a very loosely administrated region. Officials were stationed mostly in Entre-Deux-Mers, Bayonne, Dax, but some were found on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela and also on the river Garonne up to Agen. The rest of Gascony was not administered, despite being such a large area compared to other smaller, well-administered provinces. This difficulty when it came to administering the region wasn't new – it had been just as difficult for the previous Poitevin dukes to cement their authority over this area.[25] A similar state of affairs was found in the eastern provinces of Périgord and Limousin, where there was not much of a royal administrative system and practically no officials were stationed. Indeed, there were lords that ruled these regions as if they were "sovereign princes" and they had extra powers, such as the ability to mint their own coins, something English lords had been unable to do for decades. The Lusignans, for example, became rivals to the Angevins during John's rule as he attempted to consolidate his power. Officials could be stationed in Poitou, however, due to a large concentration of castles compared to the rest of Aquitaine.

Normandy was the most administrated state of the Angevin Empire after England. Prévôts and vicomtes lost their authority to baillis, who held both judicial and executive powers. These officials were introduced during the 12th century in Normandy and cause an organisation of the duchy similar to the sheriffs in England. Ducal authority was the strongest on the frontier near the Capetian royal demesne.

Toulouse was held through weak vassalage by the Count of Toulouse but it was rare for him to comply with Angevin rule. Only Quercy was directly administrated by the Angevins after Henry II's conquest in 1159, but it did remain a contested area.

Brittany, a region where nobles were traditionally very independent, was under Angevin control during Henry II and Richard I's reigns. The county of Nantes was under the firmest control. The Angevins often involved themselves in Breton affairs, such as when Henry II arranged Conan of Brittany's marriage and installed the archbishop of Dol.[26]

Economy

The economy of the Angevin Empire was quite complicated due to the varying political structure of the different fiefdoms. England and Normandy were well administered and therefore would be able to generate larger revenues than areas such as Aquitaine. This is because England and Normandy were home to more officials to collect taxes and, unlike Aquitaine, local lords were unable to mint their own coins, allowing the Angevin kings to control the economy from their administrative base of Chinon. Chinon's importance was shown by the fact that Richard seized Chinon first when he rebelled against his father in 1187, and then when John immediately rushed to Chinon after his brother's death.[28]

Money raised in England was used mostly for continental issues.[19] Also, due to the high level of administration of England and, to a lesser extent, Normandy, these areas were the only lands where revenue was consistently and relatively high.

The English revenues themselves varied from year to year. When financial records begin in 1155 to 1156, the annual income of England was £10,500, or around half what the revenue had been under Henry I.[8][29] This was due in part to The Anarchy and King Stephen's loose rule resulting in the reduction of royal authority. As time went on, royal authority improved and the revenue consequently went up to an average of £22,000 a year. Due to the preparation for the Third Crusade, revenue then increased to over £31,000 in 1190 under Richard. The number fell again to £11,000 a year whilst Richard was abroad. Between 1194–1198, revenue averaged £25,000. Under Richard's successor John, income fluctuated between £22,000 and £25,000 from 1199–1203. In order to fund for the reconquest of France, English income increased to £50,000 in 1210 but then rose to over £83,000 in 1211 before falling back down to £50,000 in 1212. Revenue then fell down to below £26,000 in 1214, and then further to £18,500 in 1215. The first three years of Henry III's reign brought in £8,000 on average due to the fragility the civil war had brought to England.

In Ireland, the revenue was fairly low at £2,000 for 1212; however, all other records did not survive. For Normandy, there were a lot of fluctuations relative to the politics of the Duchy. The Norman revenues were only £6,750 in 1180, then they reached £25,000 a year in 1198, higher than in England.[30] What was more impressive was the fact the Norman population was considerably smaller than England's, an estimated 1.5 million as opposed to England's 3.5 million.[31][32] This period has become known as the 'Norman Fiscal Revolution' due to this increase in revenue.[30]

For Aquitaine and Anjou, no records remain. However, it is not because that these regions were poor; there were large vineyards, important cities and iron mines. For example, this is what Ralph of Diceto, an English chronicler, wrote about Aquitaine:

Aquitaine overflows with riches of many kinds, excelling other parts of the western world to such an extent that historians consider it to be one of the most fortunate and flourishing of the provinces of Gaul. Its fields are fertile, its vineyards productive and its forests teem with wild life. From the Pyrenees northwards the whole countryside is irrigated by the River Garonne and other streams, indeed it is from these life-giving waters that the province takes its name.

The Capetian kings did not record such incomes, although the royal principality was more centralized under Louis VII and Philip II than it had been under Hugh Capet or Robert the Pious.[33] The wealth of the Plantagenet kings was definitely regarded as bigger; Gerald of Wales commented on this wealth with these words:

One may therefore ask how King Henry II and his sons, in spite of their many wars, possessed so much treasure. The reason is that as their fixed returns yielded less they took care to make up the total by extraordinary levies, relying more and more on these than on the ordinary sources of revenue.[34]

Petit Dutailli had commented that: "Richard maintained a superiority in resources which would have given him the opportunity, had he lived, to crush his rival." There is another interpretation, not widely followed and proven wrong, that the king of France could have raised a stronger income, that the royal principality of the king of France generated alone more incomes than all the Angevin Empire combined.[33]

Formation of the Angevin Empire

Background

The Counts of Anjou had been vying for power in northwestern France since the 10th century. The counts were recurrent enemies of the dukes of Normandy and of Brittany and often the French king. Fulk IV, Count of Anjou, claimed rule over Touraine, Maine and Nantes; however, of these only Touraine proved to be effectively ruled, as the construction of the castles of Chinon, Loches and Loudun exemplify. Fulk IV married his son and namesake, called "Fulk the Younger" (who would later become King of Jerusalem), to Ermengarde, heiress of the province of Maine, thus unifying it with Anjou through personal union.

While the dynasty of the Angevins was successfully consolidating their power in France, their rivals, the Normans, had conquered England in the 11th century. Meanwhile, in the rest of France, the Poitevin Ramnulfids had become Dukes of Aquitaine and of Gascony, and the Count of Blois, Stephen, the father of the next king of England, Stephen, became the Count of Champagne. France was being split between only a few noble families.

The Anarchy and the question of the Norman succession

In 1106, Henry I of England had defeated his brother Robert Curthose and angered his son, William Clito, who was Count of Flanders from 1127. Henry used his paternal inheritance to take the Duchy of Normandy and the Kingdom of England and then tried to establish an alliance with Anjou by marrying his only legitimate son, William, to Fulk the Younger's daughter, Matilda. However, William died in the White Ship disaster in 1120.

As a result, Henry then married his daughter Matilda to Geoffrey "Plantagenet", Fulk's son and successor; however, Henry's subjects had to accept Matilda's inheritance to the throne of England. There had been only one occurrence of a medieval European queen regnant before, Urraca of León and Castile, and it wasn't an encouraging precedent; nevertheless, in January 1127 the Anglo-Normans barons and prelates recognized Matilda as heiress to the throne in an oath. On 17 June 1128, the wedding between Matilda and Geoffrey was celebrated in Le Mans.

In order to secure Matilda's succession to the royal throne, she and her new husband needed castles and supporters in both England and Normandy, but if they succeeded, there would be two authorities in England: the king and Matilda. Henry prevented the conflict by refusing to hand over any castles to Matilda as well as confiscating the lands of the nobles he suspected of supporting her. By 1135, major disputes between Henry I and Matilda drove the nobles previously loyal to Henry I against Matilda. In November, Henry was dying; Matilda was with her husband in Maine and Anjou while Stephen, brother of the Count of Blois and Champagne, who was Matilda's cousin and another contender for the English and Norman thrones, was in Boulogne. Stephen rushed to England upon the news of Henry's death and was crowned King of England in December 1135.[36]

Geoffrey first sent his wife Matilda alone to Normandy in a diplomatic mission to be recognized Duchess of Normandy and replace Stephen. Geoffrey followed at the head of his army and quickly captured several fortresses in southern Normandy. It was then that a noble in Anjou, Robert III of Sablé, rebelled, forcing Geoffrey to withdraw and prevent an attack on his rear. When Geoffrey returned to Normandy in September 1136, the region had become plagued with internal, baronial infighting. Stephen was not able to travel to Normandy and so the situation remained. Geoffrey had found new allies with the Count of Vendôme and, most importantly, William X, Duke of Aquitaine. At the head of a new army and ready for conquest, Geoffrey was wounded and was forced to return to Anjou again. Furthermore, an outbreak of diarrhea plagued his army. Orderic Vitalis stated "the invaders had to run for home leaving a trail of filth behind them". Stephen finally arrived in Normandy in 1137 and restored order but had lost much credibility in the eyes of his main supporter, Robert of Gloucester and so Robert changed sides and supported Geoffrey and his half-sister Matilda instead. Geoffrey took Caen and Argentan without resistance, but now had to defend Robert's possessions in England against Stephen. In 1139, Robert and Matilda crossed the channel and arrived in England while Geoffrey kept the pressure on Normandy. Stephen was captured in February 1141 at the Battle of Lincoln, which prompted the collapse of his authority in both England and Normandy.

Geoffrey now controlled almost all of Normandy, but no longer had the support of Aquitaine now that William X had been succeeded by his daughter, Eleanor, who had married Louis VII of France in 1137. Louis was not concerned with the events in Normandy and England. While Geoffrey consolidated his Norman power, Matilda suffered defeats in England.[37] At Winchester, Robert of Gloucester was captured while covering Matilda's retreat so Matilda freed Stephen in exchange for Robert.

In 1142, Geoffrey was asked by Matilda for assistance but refused; he had become more interested in Normandy. Following the capture of Avranches, Mortain and Cherbourg, Rouen surrendered to him in 1144 and he then had himself anointed as Duke of Normandy. In exchange for Gisors, he was formally recognised by Louis VII. However, Geoffrey still didn't assist Matilda even as she was on the verge of defeat. After Geoffrey's investment as duke, further rebellion occurred in Anjou, including Geoffrey's younger brother, Helie, demanding Maine. It was during this period of Angevin unrest that Geoffrey then dropped the title of duke and formally invested his son Henry as Duke of Normandy in 1150, though still dominating Norman affairs.

The nominal foundation of the Angevin Empire

Stephen hadn't given up his claim on Normandy because despite Louis VII recognising Geoffrey, and later Henry in 1151, as duke in exchange for concessions in the Norman Vexin, an alliance with Louis appeared possible. Geoffrey died in 1151, making Henry Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou, with title also to Toraine and Maine. According to William of Newburgh, Geoffrey's vassals after his death forced Henry to give an oath that he would hand over Anjou to his younger brother, Geoffrey, if he was to gain the crown of England. This was the senior Geoffrey's dying wish and he had ordered that he be left without sepulture until Henry promised.

In March 1152, Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine had their marriage annulled under the pretext of consanguinity at the council of Beaugency.[38] The terms of the annulment left Eleanor as duchess of Aquitaine but still a vassal of Louis. Eight weeks later she married Henry, thus Henry became duke of Aquitaine and Gascony and count of Poitiers. Now Henry refused to give Anjou to his brother because it would mean splitting his land in two. A coalition of Henry's enemies was formed by Louis VII: Stephen of England and his son Eustace IV of Boulogne (married to Louis' sister); Henry I, Count of Champagne (betrothed to Louis' daughter), Robert of Dreux (Louis' brother) and Henry's brother, Geoffrey, who saw he wouldn't receive Anjou.

In July 1152, Capetian troops attacked Aquitaine while Louis, Eustace, Henry of Champagne, and Robert attacked Normandy. Geoffrey raised a revolt in Anjou while Stephen attacked Angevin loyalists in England. Several Anglo-Norman nobles switched allegiance, sensing an impending disaster. Henry was about to sail for England to pursue his claim when his lands were attacked. He first reached Anjou and compelled Geoffrey to surrender. He then took the decision to sail for England in January 1153 to meet Stephen. Luckily enough, Louis fell ill and had to retire from the conflict while Henry's defences held against his enemies. After seven months of battles and politics, Henry failed to get rid of Stephen but then Stephen's son, Eustace, died in dubious circumstances, "struck by the wrath of god." Stephen gave up the struggle by ratifying the Treaty of Winchester, making Henry his heir on condition that the landed possessions of his family were guaranteed in England and France—the same terms Matilda had previously refused after her victory at Lincoln. Henry became King Henry II of England upon Stephen's death on 25 October 1154. Subsequently, the question was again raised of Henry's oath to cede Anjou to his brother Geoffrey. Henry received a dispensation from Pope Adrian IV under the pretext the oath had been forced upon him, and he proposed compensations to Geoffrey at Rouen in 1156. Geoffrey refused and returned to Anjou to rebel against his brother. Geoffrey may have had a strong claim, but his position was weak. Louis would not interfere since Henry paid homage to him for his continental possessions. Henry crushed Geoffrey's revolt, and Geoffrey had to be satisfied with an annual pension. The Angevin Empire had now been formed.

Expansions of the Angevin Empire

In the earlier years of his reign, Henry II claimed further lands and worked on the creation of a ring of vassal states as buffers, especially around England and Normandy. The most obvious areas to expand, where large claims were held, were Scotland, Wales, Brittany, and, as an ally rather than a new dominion, Flanders.

King David I of Scotland had taken advantage of The Anarchy to seize Cumberland, Westmorland and Northumberland. In Wales, important leaders like Rhys of Deheubarth and Owain Gwynedd had emerged. In Brittany, there is no evidence that the Duke of Brittany, namely Eudes II, had recognised the Norman overlordship. Two vital frontier castles, Moulins-la-Marche and Bonmoulins, had never been taken back by Geoffrey Plantagenet and were in the hands of Robert of Dreux. Count Thierry of Flanders had joined the alliance formed by Louis VII in 1153. Further south, the Count of Blois acquired Amboise. From Henry II's perspective, these territorial issues needed solving.[8]

King Henry II showed himself to be an audacious and daring king as well as being active and mobile; Roger of Howden stated that Henry travelled across his dominions so fast that Louis VII once exclaimed that "The king of England is now in Ireland, now in England, now in Normandy, he seems rather to fly than to go by horse or ship." [39] Henry was often more present in France than in England;[40] Ralph de Diceto, Dean of St Paul's, said with irony:

There is nothing left to send to bring the king back to England but the Tower of London.[41]

Castles and strongholds in France

Henry II bought Vernon and Neuf-Marché back in 1154.[42] This new strategy now regulated the Plantagenet-Capetian relationship. Louis VII had been unsuccessful in his attempt to break Henry II down. Because of the Angevin control of England in 1154, it was pointless to object to the superiority of the overall Angevin forces over the Capetian ones. However, Henry II refused to back down despite Louis' apparent change of policy until the Norman Vexin was entirely recovered. Thomas Becket, then the current Chancellor of England, was sent as ambassador to Paris in the summer of 1158 to lead negotiations.[43] He displayed all the wealth the Angevins could provide, and according to William FitzStephen, a Frenchman exclaimed "If the Chancellor of England travels in such splendor, what must the king be?"[44] Louis VII's daughter, Margaret, who was still a baby, was betrothed to Henry's heir, his eldest son, Henry the Young King with a dowry of the Norman Vexin.[43] Henry II was given back the castles of Moulins-la-Marche and Bonmoulins.[45] Theobald V, Count of Blois handed Amboise back to him.

Flanders

The relationship between Thierry of Alsace, Count of Flanders, who had taken part in the assaults against Henry II with Louis VII, and Henry II, who had expelled all Flemish mercenaries after his accession to the throne,[46] was not cordial at first. However, the wool trade between England and Flanders was profitable and meant that the count and Henry favoured a cordial relationship between the two of them. This relationship peaked when the Count appointed Henry guardian of his eldest son, Philip, who had been left as regent,[47] so that he could undertake a pilgrimage to Jerusalem without concern in 1157. In 1159, William of Blois died without an inheritance, he was Stephen's last son, leaving the titles of Count of Boulogne and Count of Mortain vacant. Henry II absorbed the County of Mortain but wanted to grant Boulogne to Thierry's second son, Matthew, who married Marie of Boulogne. The title of Count of Boulogne was accompanied with important manors in London and Colchester.

England traded much of its wool with Flanders via the port of Boulogne.[48] An alliance with these two counties was then logically sealed by this wedding and the concessions of manors. Henry II had to get Marie out of her convent first, which had been a common practice in England since the Normans. In 1163, the few official remaining documents show Henry II and Thierry renewed a treaty that had been made between Henry I of England, and Robert II of Flanders. Flanders would provide Henry II with knights in exchange of an annual tribute in money, known as a "money-fief".[49]

Brittany

In Brittany, Duke Conan III declared his son Hoël a bastard and disinherited him on his deathbed in 1148.[50] It was his sister Bertha who became Duchess of Brittany making her husband of the time, Eudes, nominally Duke.[50] Hoël had to be satisfied as Count of Nantes. Bertha was the widow of Alan de Bretagne with whom she already had a son, Conan.[51] Conan, who had become Earl of Richmond in 1148, was Henry II's perfect candidate to become the future Duke of Brittany after Bertha, as any Duke with possessions of importance in England would be easier to control as they are directly a vassal of the English King.[52]

In 1156, Brittany was hit by civil unrest when Bertha died, ending in Conan IV's accession.[50] Meanwhile, in Nantes, the population attempted to oust their Count, Hoël, and called on Henry II for help.[52] Geoffrey, Henry's brother, was installed as Count by Henry, but died in 1158.[52] Conan IV then briefly ruled as Count, but Henry took the title that same year by mustering an army in Avranches to threaten Conan.[53] In 1160 Henry's cousin Margaret of Scotland married Conan.[54] Henry then supported Breton independence in 1161 when he secured the Archbishopric of Dol.[55] The jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Tours would have overrun into Brittany if Henry hadn't appealed to Rome.[55] Henry then appointed the archbishop of Dol, Roger du Hommet.[56][57] Without a tradition of a strong rule in Brittany, discontent grew among the nobles in the years following, culminating in a baronial revolt that Henry II ended in 1166.[58][59] He betrothed his own 7-year-old son, Geoffrey, to Conan's daughter, Constance, and later forced Conan to abdicate for his future son-in-law, making Henry II the ruler of Brittany, yet not the Duke.[60] Breton nobles strongly opposed this, and more attacks on Brittany occurred in the following years until 1173.[61] Each of these invasions were followed by confiscations, and Henry II installed his men, William Fitzhamo and Rolland of Dinan, in the area.[62] Although it was not formally part of the Plantagenet fiefdom, Brittany was under firm control.[63]

Scotland

.png.webp)

Henry II met Malcolm IV in 1157 about Cumberland, Westmorland and Northumberland previously seized by his grandfather, David I of Scotland. In 1149, before Henry II became powerful, he made an oath to David that the lands north of Newcastle should belong to the King of Scotland forever. Malcolm reminded him of this oath but Henry II did not comply. There is no evidence that Henry II got a dispensation from the pope this time, as William of Newburgh put it, "prudently considering it was the king of England who had the better of the argument by reason of his much greater power."

Malcolm IV gave up and paid homage in return for Huntingdon, which he inherited from his father.[64][65]

William the Lion, the next King of Scotland, was unhappy with Henry II since he was given Northumberland by David I in 1152 and therefore lost it to Henry II when Malcolm IV handed it back in 1157.

As a part of the coalition set by Louis VII, William the Lion first invaded Northumberland in 1173 and then again in 1174, as a result he was captured near Alnwick and had to sign the tough Treaty of Falaise. Garrisons were to be set in the castles of Edinburgh, Roxburgh, Jedburgh and Berwick.[18] Southern Scotland was from then under firm control just as Brittany was. Richard I of England would end the Treaty of Falaise in exchange for money to fund his own crusade, setting a context for cordial relationships between the two kings.

Wales

Rhys of Deheubarth, also called Lord Rhys, and Owain Gwynedd were closed to negotiations. Henry II had to attack Wales three times, in 1157, 1158 and 1163 to have them answer his summons to the court. The Welsh found his terms too harsh and largely revolted against him. Henry then undertook a fourth invasion in 1164, this time with a massive army. According to the Welsh chronicle Brut y Tywysogion, Henry raised "a mighty host of the picked warriors of England and Normandy and Flanders and Anjou and Gascony and Scotland" in order to "carry into bondage and to destroy all the Britons".[66]

Bad weather, rains, floods, and constant harassment from the Welsh armies slowed the Angevin army and prevented the capture of Wales (see the Battle of Crogen); a furious Henry II had Welsh hostages mutilated. Wales would remain safe for a while, but the invasion of Ireland in 1171 pressured Henry II to end the issue through negotiations with Lord Rhys.[20]

Ireland

There were further plans of expansion considered as Henry II's last brother didn't have a fiefdom. The Holy See was most likely to support a campaign in Ireland which would bring its church into the Christian Latin world of Rome. Henry II was given Rome's blessing in 1155 under the form of a Papal bull,[67] but had to postpone the invasion of Ireland because of all the problems in his domains and around them. In the terms of the Bull Laudabiliter, "Laudably and profitably does your magnificence contemplate extending your glorious name on earth."

William X, Count of Poitou died in 1164 without being installed in Ireland, but Henry II didn't give up on the conquest of Ireland. In 1167 -Dermot of Leinster- an Irish King, was recognised as "prince of Leinster" by Henry II and was allowed to recruit soldiers in England and Wales to use in Ireland against the other Kings. The knights first met great success in carving themselves lands in Ireland, so much it worried Henry II enough to land himself in Ireland in October 1171 near Waterford and confronted to such demonstration of power most native kings of Ireland recognised him as their lord. Even Rory O' Connor, the king of Connacht and High King of Ireland paid homage to Henry II. Henry II installed some of his men in strongholds like Dublin and Leinster (as Dermot was dead). He also gave unconquered kingdoms such as Cork, Limerick and Ulster to his men and left the Normans carving their lands in Ireland. In 1177 he made John, his son, the first Lord of Ireland, though John was too young and landed in Ireland only in 1185. He failed to install his authority on the land and had to return to Henry II. Only 25 years later John would return to Ireland while others built castles and installed their interests.

Toulouse

Much less tenable was the claim over Toulouse, the fortified seat of the County of Toulouse. Eleanor's ancestors claimed the large county, as it had been the central power of the ancient Duchy of Aquitaine in the times of Odo the Great.[15] However Henry II and possibly Eleanor were likely not related to this ancient line of dukes; Eleanor was a Ramnulfid, while Henry II was an Angevin.

Toulouse was larger, more heavily fortified, and much richer than many cities of the time. It was of strategic importance, as the largest state of the Kingdom of France, between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean, and including significant towns such as Narbonne, Cahors, Albi, Nîmes and Carcassonne. The recurrent conflicts with Toulouse would be called the Forty Years War with Toulouse by William of Newburgh.

In June 1159, Henry II's forces gathered in Poitiers. They included troops from all of his fiefdoms from Gascony to England, and reinforcements sent by Thierry and King Malcolm IV of Scotland. Even a Welsh prince joined the fray. The only larger armies of the times were those raised for major crusades.[68] Henry II attacked from the north; his allies the Trencavels and Ramon Berenguer opened a second front. Henry II couldn't capture Toulouse proper since his overlord, King Louis VII of France, was part of the defence and he didn't want to set an example to his vassals or have to deal with keeping his sovereign prisoner.[68] Henry II did capture Cahors along with castles in the Garonne valley in the Quercy region.

Henry II returned in 1161, but too busy with conflicts elsewhere in his fiefdom, he left his allies fighting against Toulouse. Alfonso II the King of Aragon, himself having interests there, joined the war. In 1171 Henry II's alliance was bolstered by another of Raymond V's enemies, Humbert of Maurienne.

In 1173, in Limoges, Raymond finally gave up after over a decade of constant fights. He paid homage to Henry II, to his son Henry, and to his other son Richard the Lionheart, newly appointed new Duke of Aquitaine.[69]

Pinnacle of the Angevin Empire

The attacks on Toulouse made clear that peace between Louis VII and Henry II was not peace at all but just an opportunity for Henry to make war elsewhere.[70] Louis was in an awkward position: his subject, Henry, was largely more powerful than he was and Louis had no male heir. Constance, his second wife, died in childbirth in 1160 and Louis VII announced he would remarry at once, in the urgent need of a male heir, with Adèle of Champagne. Henry II's son, Henry, two years old, was finally married to Margaret under the pressure of Henry II, and, as declared in 1158, the Norman Vexin went to him as Margaret's dowry. If Louis VII died without a male heir, Henry would have been a strong candidate for the French throne.

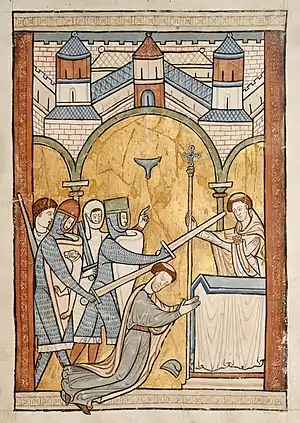

In 1164, Louis found a dangerous ally in Archbishop Thomas Becket.[71] Louis and Becket had met previously in 1158, but now the circumstances were different; France was already refuge to a few clerical refugees, and Louis was known as Rex Christianisimus (most Christian king), called so by John of Salisbury.[71] Becket took refuge in France, and following this there were growing conflicts between Henry II and Becket. Henry finally provoked Becket's murder in 1170 by announcing, "What miserable traitors have I nourished in my household who led their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk!"[72] Christendom blamed Henry, whereas Louis gained widespread approval due to his protection of Becket. Louis' secular power was much weaker than Henry's but Louis now had the moral advantage.

In 1165, hopes of Henry II's son's future accession to the French throne were dashed when Adèle gave birth to a son, Philip. Following this, the fragile Anglo-French peace ended. In 1167, Henry II marched into Auvergne, and in 1170 he also attacked Bourges. Louis VII answered by raiding the Norman Vexin, forcing Henry II to move his troops north, giving Louis the opportunity to free Bourges. At this point, John Gillingham mentions in The Angevin Empire that he believes Louis "must have wondered whether there was ever going to be an end to Henry's aggressively expansionist policies".[73]

Henry II did not treat his territories as a coherent empire as the term "Angevin Empire" would suggest, but as private, individual possessions that he planned to distribute to his children. Henry, 'The Young King', was crowned King of England in 1170 (though he never ruled); Richard became Duke of Aquitaine in 1172; Geoffrey became Duke of Brittany in 1181; John became Lord of Ireland in 1185; Eleanor was promised to Alfonso VII with Gascony as dowry during the campaign against Toulouse in 1170. This partition of the lands between his children made it much harder for him to control them, as now they could fund their own ventures with their estates and attempt to overrule their father in their respective dominions.

Following his coronation, in 1173, Henry, 'the Young King', asked for part of his inheritance, at least England, Normandy, or Anjou, but his father refused. Young Henry then joined Louis at the French court to otherthrow his father together, and his mother, Eleanor, joined the new revolt against Henry II. Both Richard and Geoffrey soon joined their brother. Enemies that Henry II had made previously now joined the conflict with Louis, including King William the Lion of Scotland, Count Philip of Flanders, Count Matthew of Boulogne and Count Theobald of Blois. Henry II emerged victorious; his wealth meant he could recruit large numbers of mercenaries, and he had captured and imprisoned his wife, Eleanor, early on and captured William the Lion and forced him into the Treaty of Falaise. Henry bought the County of Marche, then he asserted that the French Vexin and Bourges should be given back at once. However, this time there was no invasion to back the claim.

Richard I and Philip II

Louis VII died in 1180 and was succeeded by his 15-year-old son, crowned as Philip II. The man who would later become arguably his main rival, Richard, had administered Aquitaine since 1175 but his policy of centralisation of the Aquitanian government had grown unpopular in the eastern part of the Duchy, notably Périgord and Limousin. Richard was further disliked in Aquitaine due to his apparent disregard for Aquitaine's customs of inheritance, as shown by events in Angoulême in 1181.[74] If Richard was unpopular in Aquitaine though, Philip was equally disliked by his contemporaries with comments describing him as: astute, manipulative, calculating, penurious and ungallant ruler.[75]

In 1183, Henry the Young King joined a revolt to overthrow the unpopular Duke Richard, led by the viscount of Limoges and Geoffrey of Lusignan, where Henry would take Richard's place. Joined by Philip II, Count Raymond V of Toulouse, and Duke Hugh III of Burgundy, Henry died suddenly of a fatal illness in 1183, saving Richard's position.[76]

Richard, now Henry II's oldest son, became Henry's heir. Henry ordered him to hand Aquitaine to his brother, John, but Richard refused. Henry was busy with Welsh princes contesting his authority, William the Lion was asking for his castles to be given back that had been taken in the Treaty of Falaise, and now Henry the Young King was dead, Philip wanted the Norman Vexin handed back. Henry II decided instead to insist Richard to nominally surrender Aquitaine to his mother whilst Richard would retain actual control. Still, in 1183, Count Raymond had taken Cahors back and so Henry II asked Richard to mount an expedition to retake the city. At the time, Geoffrey of Brittany had been quarrelling violently with Richard and Philip planned to use this, but Geoffrey's death in 1186 in a tournament killed the plot. The next year, Philip and Richard had become strong allies:

The King of England was struck with great astonishment, and wondered what [this alliance] could mean, and, taking precautions for the future, frequently sent messengers into France for the purpose of recalling his son Richard; who, pretending that he was peaceably inclined and ready to come to his father, made his way to Chinon, and, in spite of the person who had the custody thereof, carried off the greater part of his father's treasures, and fortified his castles in Poitou with the same, refusing to go to his father.

In 1188, Raymond attacked again, joined by the Lusignans, vassals of Richard. It was rumoured that Henry himself had financed the revolts. Philip attacked Henry in Normandy and captured strongholds in Berry, then they met to discuss peace again. Henry refused to make Richard his heir, with one story reporting that Richard said "Now at last, I must believe what I had always thought impossible."[77]

Henry's plans collapsed. Richard paid homage to Philip for the continental lands his father held then they attacked Henry together. The Aquitanians refused to help whilst the Bretons seized the opportunity to attack him too. Henry's birthplace, Le Mans, was captured and Tours fell. Henry was encircled at Chinon and was compelled to surrender. He gave a large tribute in money to Philip and swore that all his subjects in France and England would recognise Richard as their lord. Henry died two days later, after learning John, the only son that had previously never betrayed him, had joined Richard and Philip. He was buried in Fontevraud Abbey.

Eleanor, who had been Henry's hostage since the 1173-4 revolt, was freed while Rhys ap Gruffydd, ruler of Deheubarth in South Wales, began to reconquer the parts of Wales that Henry had annexed. Richard was crowned King Richard I of England in Westminster Abbey in November 1189, and had already been installed as Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou and Duke of Aquitaine. Richard demanded Philip surrender the Vexin but then the issue was settled when Richard announced he would marry Alys, Philip's sister. Richard also recognised Auvergne as being in Philip's royal demense and not as part of the Duchy of Aquitaine, as Henry had claimed. The two lion kings, William the Lion, King of Scotland, and Richard, opened negotiations to revoke the Treaty of Falaise and an agreement was reached.[78]

The Third Crusade

The next priority for Richard I was the Third Crusade; it had been delayed since Richard had taken the cross in 1187. This was not just a religious pilgrimage however; his great-grandfather, Fulk had been King of Jerusalem and the current pretender to the throne, Guy de Lusignan was a Poitevin noble, related to many of Richard's vassals, while Guy's wife—Sybilla—was Richard's cousin. The crusade, excluding disputes in France, would be the main reason for Richard's absence from England; he would spend less than six months of his reign in England.[79]

Before leaving, Richard consolidated his reign over the Empire. He suspected Count Raymond would expand his lands into Aquitaine so he allied with Sancho VI the Wise, the King of Navarre, by marrying his daughter, Berengaria, to counter the threat. They married in 1191 in Limassol, Cyprus, therefore repudiating Alys, Philip's sister, but the issue had been settled earlier in Messina. To placate Philip, Richard had given him 10,000 marks and agreed that if he had two sons, the youngest would take Normandy, Aquitaine, or Anjou and rule it under Philip.[80][81] The administration Richard left behind worked considerably well, as an attack from Raymond was repelled with the help of Navarre.

The siege of Acre, which had been the last Christian stronghold in Holy Land, was over by July and Philip decided to return to France. It is unclear whether Philip returned due to dysentery, anger towards Richard, or that he thought he could gain Artois following the death of the Count of Flanders, as he had married the Count's daughter.[82] Whilst back at France, Philip boasted he was 'going to devastate the king of England's lands' and, in January 1192, he demanded from the seneschal of Normandy, William FitzRalph, the Vexin, claiming that the treaty he had signed with Richard in Messina contained the intention of Richard that, as the Vexin had been Alys' dowry and since Richard had married Berengaria, he was entitled to the land.[83] Although Philip threatened invasion, Eleanor of Aquitaine intervened in stopping her son, John, from promising to concede the land. Philip's nobles refused to attack the lands of an absent crusader, though Philip instead gained lands in Artois. Philip's return did result in castles throughout the empire being in a "state of readiness".[84] The alliance with Navarre helped again when Philip attempted to incite revolt in Aquitaine but failed.

King Richard left the Holy Land over a year later than Philip in October 1192, and possibly could have retrieved his empire intact had he reached France soon after. However, during the crusade Leopold V, Duke of Austria, had been insulted by Richard, and so he arrested Richard near Vienna, on his journey home. Richard had been forced to go through Austria as the path through Provence was blocked by Raymond in Toulouse. Leopold also accused Richard of sending assassins to murder his cousin Conrad, and then handed Richard over to his overlord, Emperor Henry VI.

In January 1193, Richard's brother, John, was summoned to Paris, where he did homage to Philip for all of Richard's lands, and promised to marry Alys with Artois as her dowry. In return, the Vexin and the castle of Gisors would be given to Philip. With the help of Philip, John went to invade England and incite rebellion against Richard's justiciars. John failed and then had worse luck when it was discovered Richard was alive, which was unknown until this point.[85] At the imperial court in Speyer, Richard was put on trial where he spoke very well for himself:

When Richard replied [to the charges against him] he spoke so eloquently and regally, in so lionhearted a manner, that it was as though he had forgotten where he was and the undignified circumstances in which he had been captured and imagined himself to be seated on the throne of his ancestors at Lincoln or Caen.

— William the Breton, Phillipidos, iv, 393-6, in Oeuvres de Rigord et de Guillaume le Breton, ed. H. F. Delaborde, ii (Paris, 1885)

Richard was to be set free after a deal was finalised in June 1193. However, whilst the discussions had been going on, Philip and John had created war in three different areas of the Angevin Empire. Firstly, in England, John had attempted to take over, asserting that Richard would never return. The justiciars pushed him and his forces back to the castles of Tickhill and Windsor, which were besieged. A deal was made that allowed John to keep Tickhill and Nottingham, but return his other possessions.[86] Secondly, in Aquitaine, Ademar of Angoulême claimed that he held his county directly as a fief of Philip's, not as a vassal of the Duke of Aquitaine. He raided Poitou but was stopped by the local officials, and captured.[87] Thirdly, and finally, in Normandy, Philip had taken Gisors and Neaufles, and the lords of Aumâle, Eu, and other smaller lordships, as well as the counts of Meulan and Perche, had surrendered to Philip.[88] Philip failed to take Rouen in April but gained other castles; Gillingham summarised, saying that "April and May 1193 were wonderfully good months for Philip".[88]

When Philip heard of Richard's deal with Emperor Henry, he decided to consolidate his gains by forcing Richard's regents to concede with a treaty at Mantes in July 1193. Firstly, John was handed back his estates in both England and France. Secondly, Count Ademar was to be released and no Aquitanian vassals were to be charged or penalised. Thirdly, Richard was to give four major castles to Philip and pay the cost of garrisoning them, along with other compensation.[89]

Richard failed to be reconciled with his brother, John, and so John went to Philip and created a new treaty in January 1194, surrendering all of Normandy east of the Seine except Rouen and Tours and the other castles of Touraine to Philip, Vendôme to Louis of Blois, and Moulins and Bonsmoulins to Count Geoffrey of Perche. The county of Angoulême was to be independent of the duchy of Aquitaine. The Angevin Empire was being completely split by John's actions.[90] Philip continued to bargain with Emperor Henry, and the emperor cut a new deal with Richard after being offered large sums of money by Philip and John. Richard would surrender the kingdom of England to Henry, who would then give it back as a fief of the Holy Roman Empire. Richard had become a vassal of Henry. Richard was released, and whilst still in Germany he paid for the homage of the archbishops of Mainz and Cologne, the bishop of Liège, the duke of Brabant, the duke of Limburg, the count of Holland, and other lesser lords. These allies were the beginning of a coalition against Philip.[91]

Although Philip had been granted many Norman territories, it was only nominally. In February, he captured Évreux, Neubourg, Vaudreuil, and other towns. He also received the homage of two of Richard's vassals, Geoffrey de Rancon and Bernard of Brosse. Philip and his allies were now in control of all the ports of Flanders, Boulogne, and eastern Normandy. Richard finally returned to England and landed at Sandwich on 13 March 1194.[92]

Richard after captivity

Richard was in a difficult position; Philip II had taken over large parts of his continental domains and had inherited Amiens and Artois. England was Richard's most secure possession; Hubert Walter, who had been to the crusade with Richard, was appointed his justiciar.[93] Richard besieged the remaining castle that had declared allegiance to John and not capitulated: Nottingham Castle.[93] He then met with William the Lion in April and rejected William the Lion's offer to purchase Northumbria, to which William possessed a claim.[94] Later, he took over John's Lordship of Ireland and replaced his justiciar.[95]

Richard I had merely crossed the English Channel to claim back his territories that John Lackland betrayed Philip II by murdering the garrison of Évreux and handing the town down to Richard I. "He had first betrayed his father, then his brother and now our King" said William the Breton. Sancho the Strong, the future King of Navarre, joined the conflict and attacked Aquitaine, capturing Angoulème and Tours. Richard himself was known to be a great military commander.[96] The first part of this war was difficult for Richard who suffered several setbacks, as Philip II was, as described by John Gillingham, "a shrewd politician and a competent soldier."[97] But by October the new Count of Toulouse, Raymond VI, left the Capetian side and joined Richard's. He was followed by Baldwin IV of Flanders, the future Latin Emperor, as this one was contesting Artois to Philip II. In 1197, Henry VI died and was replaced by Otto IV, Richard I's own nephew. Renaud de Dammartin, the Count of Boulogne and a skilled commander, also deserted Philip II. Baldwin IV was invading Artois and captured Saint-Omer while Richard I was campaigning in Berry and inflicted a severe defeat on Philip II at Gisors, close to Paris. A truce was accepted, and Richard I had almost recovered all Normandy and now held more territories in Aquitaine than he had before. Richard I had to deal with a revolt once again, but this time from Limousin. He was struck by a bolt in April 1199 at Châlus-Chabrol and died of a subsequent infection. His body was buried at Fontevraud like his father.

Collapse of the Angevin Empire

John's accession to the throne

Following the news of King Richard I's death in 1199, John attempted to seize the Angevin treasury at Chinon in order to impose his control of the Angevin government.[98] Angevin custom, however, gave John's nephew, Duke Arthur, son of Geoffrey of Brittany, a stronger claim on Richard's throne, and the nobles of Anjou, Maine, and Touraine declared in favour of Arthur on 18 April 1199.[99] Philip II of France had taken Évreux and the Norman Vexin,[100] and a Breton army had seized Angers by this point. Le Mans refused to declare allegiance to John, so he ran to Normandy, where he was invested as duke in Rouen on 25 April. He returned to Le Mans with an army where he punished its citizens and then left for England. England had declared its support for John thanks to William Marshal and Archbishop Hubert Walter of Canterbury's support.[101] He was crowned on 27 May in Westminster Abbey.

Due to his mother's support, Aquitaine and Poitou supported John, and only Anjou, Maine, Touraine, and Brittany remained disputed. In May, Aimeri, Viscount of Thouars, who was chosen by John to be his seneschal in Anjou, attacked Tours in an attempt to capture Arthur of Brittany.[102] Aimeri failed, and John was forced to return to the continent in order to secure his rule, through a truce with Philip II, after Philip had launched attacks on Normandy.[103] Philip was forced into the truce due to John's support from fifteen French counts and support from counts in the Lower Rhine, such as with Count Baldwin of Flanders, who he met in August 1199 in Rouen, and Baldwin did John homage.[103][104] From a position of strength, John was able to go on the offensive, and he won William des Roches, Arthur's candidate for the Angevin seneschal, to his cause following an incident with Philip.[105] William des Roches also brought Duke Arthur and his mother, Constance, as prisoners to Le Mans on 22 September 1199, and the succession appeared to have been secured in favour of John.[104]

Despite the escape of Arthur and Constance with Aimeri of Thouars to Philip II, and many of Richard's previous allies in France, including the counts of Flanders, Blois, and Perche, leaving for the Holy Land,[104] John was able to make peace with Philip that secured his accession to his brother's throne.[106] John met with Philip and signed the Treaty of Le Goulet in May 1200, where Philip accepted John's succession to the Angevin Empire, and Arthur became his vassal, but John was forced to break his German alliances, accept Philip's gains in Normandy, and cede lands in Auvergne and Berry.[106][107] John was also to accept Philip as his suzerain overlord and pay Philip 20,000 marks.[106] As W. L. Warren notes, this Treaty began the practical dominance of the French king over France, and the ruler of the Angevin Empire was no longer the dominating noble in France.[108] In June 1200, John visited Anjou, Maine, and Touraine, taking hostages from those he distrusted, and visiting Aquitaine, where he received homage from his mother's vassals, returning to Poitiers in August.[109]

Lusignan rebellion and the Anglo-French war

Following the annulment of John's first marriage to Isabelle of Gloucester, John married Isabella, the daughter and heiress of Count Aymer of Angoulême, on 24 August 1200.[110] Angoulême had considerable strategic significance, and the marriage made "very good political sense", according to Warren.[110] However, Isabella had been betrothed to Hugh of Lusignan, and John's treatment of Hugh following the marriage, including the seizure of La Marche, led Hugh to appeal to Philip II.[111] Philip summoned John to his court, and John's refusal resulted in the confiscation of John's continental possessions excluding Normandy in April 1202 and Philip accepting Arthur's homage for the lands in July.[111] Philip went on to invade Normandy as far as Arques in May, taking a number of castles.[100][112]

John, following a message from his mother, Eleanor, rushed from Le Mans to Mirebeau, attacking the town on 1 August 1202, with William des Roches.[113] William promised to direct the attack on condition he was consulted on the fate of Arthur,[113] and successfully captured the town along with over 200 knights, including three Lusignans.[112] John also captured Arthur and Eleanor, Fair Maid of Brittany sister of Arthur, but antagonised William,[114] failing to consult him on the future of Arthur, and causing him to leave John along with Aimeri of Thouars and siege Angers.[115] Under the control of Hubert de Burgh in Falaise, Arthur disappeared and John was seen as responsible for his murder,[116] with his sister, the Fair Maid, never released. The Angevin Empire was under attack in all areas, with the following year, 1203, being described as that "of shame" by Warren.[117] In December 1203, John left Normandy never to return, and on 24 June 1204, Normandy capitulated with the surrender of Rouen.[100] Tours, Chinon, and Loches had fallen by 1205.[116]

On the night of 31 March 1204, John's mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, died, causing a rush of "most of Poitou...to do homage to the king of France".[118] King Alfonso of Castile invaded Gascony, using the claim of his wife, John's sister Eleanor.[119] When John to the continent in June 1206, only the resistance led by Hélie de Malemort, Archbishop of Bordeaux had prevented Alfonso's success.[118] By the end of John's expedition on 26 October 1206, most of Aquitaine was secure.[120] A truce was made between John and Philip to last for two years.[120] The Angevin Empire had been reduced to England, Gascony, Ireland, and parts of Poitou, and John would not return to his continental possessions for eight years.[121]

Return to France

By the end of 1212, Philip II was preparing an invasion of England.[122] Philip aimed to crown his son, Louis, king of England, and at a council at Soissons in April 1213, he drafted a possible relationship between the future France and England.[122] On 30 May, William Longespée, Earl of Salisbury, succeeding in crushing the French invasion fleet in the Battle of Damme and preventing French invasion.[121] In February 1214, John landed in La Rochelle after creating alliances headed by the Holy Roman Emperor, Otto.[123] The aim was for the Earl of Salisbury and John's German allies to attack Philip from the north, whilst John attacked from the south.[124]

By June 1214, John had the support of the houses of Lusignan, Mauléon, and Thouars,[125] but when John advanced into Anjou, capturing Angers on 17 June, the desertion of his Poitevin allies forced a retreat back to La Rochelle.[124] On 27 July, John's German allies lost the Battle of Bouvines, with many prisoners taken, including the Earl of Salisbury.[126] On 18 September, John and Philip agreed to a truce that would last until Easter 1220.[125][127] In October 1214, John returned to England.[127]

Capetian invasion of England

.jpg.webp)

Following the agreement at Runnymede in June 1215, rebel English barons felt that John would not observe the terms of Magna Carta, and offered the English crown to Philip's son, Louis.[128] Louis accepted, landing in Kent on 21 May 1216, with 1,200 knights.[129] Louis seized Rochester, London, and Winchester, whilst John was deserted by several nobles, including the Earl of Salisbury.[129] In August, only Dover, Lincoln, and Windsor remained loyal to John in the east, and Alexander II of Scotland travelled to Canterbury to pay homage to Louis.[128]

In September 1216, John began his attack, marching from the Cotswolds, feigning an offensive to relieve the besieged Windsor Castle, and attacking eastwards around London to Cambridge to separate the rebel-held areas of Lincolnshire and East Anglia.[130] In King's Lynn, John contracted dysentery.[130] On 18 October 1216, John died.[129]

Louis was defeated twice following John's death in 1217, in Lincoln in May, and at Sandwich in August, resulting in his withdrawal from the claim on the throne and England with the Treaty of Lambeth in September.[131]

Cultural influence

The hypothetical continuation and expansion of the Angevin Empire over several centuries has been the subject of several tales of alternate history. Historically, both English and French historians had viewed the juxtaposition of England and French lands under Angevin control as something of an aberration and an offence to national identity. To English historians the lands in France were an encumbrance, while French historians considered the union to be an English empire.[132]

The ruling class of the Angevin Empire was French-speaking.[133]

The 12th century is also the century of Gothic architecture, first known as opus francigenum, from the work of the Abbot Suger at Saint Denis in 1140. The Early English Period began around 1180 or 1190, in the times of the Angevin Empire,[134] but this religious architecture was totally independent of the Angevin Empire, it was just born at the same moment and spread at those times in England. One of the strongest influences on architecture directly associated with the Plantagenets is about kitchens.[135]

Richard I's personal arms of three golden lions passant guardant[136] on a red field appear in most subsequent English royal heraldry, and in variations on the flags of both Normandy and Aquitaine.[137]

From a political point of view, continental issues were given more attention from the monarchs of England than the British ones already under the Normans.[138] Under Angevin lordship things became even more clear as the balance of power was dramatically set in France and the Angevin kings often spent more time in France than England.[139] With the loss of Normandy and Anjou, the fiefdom was cut in two and then the descendants of the Plantagenets can be regarded as English kings accounting Gascony in their domain.[140] This is accordant with the newfound Lordship of Aquitaine being conferred upon the Black Prince of Wales, passing thence to the House of Lancaster, which had pretensions to the Crown of Castile, much as Edward III had to France. It was this assertion of power from England onto France and from Aquitaine onto Castile which marked the difference from earlier in the Angevin period.

See also

- House of Ingelger

- Angevin kings of England

- House of Plantagenet

- Counts and Dukes of Anjou

- Capetian–Plantagenet rivalry

Notes and references

- The term imperium is used at least once in the 12th century, in the Dialogus de Scaccari (c. 1179), Per longa terrarum spatia triumphali victoria suum dilataverit imperium (Canchy, England, p. 118; Holt, 'The End of the Anglo-Norman Realm', p. 229). Some 20th-century historians have avoided the term empire, Robert-Henri Bautier (1984) used espace Plantagenêt, Jean Favier used complexe féodal. Empire Plantagenêt nevertheless remains current in French historiography. Aurell, Martin (2003). L'Empire des Plantagenêt, 1154–1224. Perrin. p. 1. ISBN 9782262019853.

- John H. Elliott (2018). Scots and Catalans: Union and Disunion. Yale University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780300240719.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 2. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Norgate, Kate (1887). England under the Angevin Kings. London: Macmillan. pp. 393.

- Aurell, Martin (2003). L'Empire des Plantagenêt, 1154–1224. Perrin. p. 11. ISBN 9782262019853.

En 1984, résumant les communications d'un colloque franco-anglais tenu à Fontevraud (Anjou), lieu de mémoire par excellence des Plantagenêt, Robert Henri-Bautier, coté français, n'est pas en reste, proposant, pour cette 'juxtaposition d'entités' sans 'aucune structure commune' de substituer l'imprécis 'espace' aux trop contraignants 'Empire Plantagenêt' ou 'Etat anglo-angevin'.

- "Angevin, adj. and n." Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- E.M., Hallam (1983). Capetian France 937–1328. Longman. p. 221. ISBN 9780582489103.

Closer investigation suggests that several of these assumptions are unfounded. One is that the Angevin dominions ever formed an empire in any sense of the word.

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Penguin. pp. 191. ISBN 9780140148244.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 3. ISBN 9780713162493.

Unquestionably if used in conjunction with atlases in which Henry II's lands are coloured red, it is a dangerous term, for then overtones of the British Empire are unavoidable and politically crass. But in ordinary English usage 'empire' can mean nothing more specific than an extensive territory, especially an aggregate of many states, ruled over by a single ruler. When coupled with 'Angevin', it should, if anything, imply a French rather than a 'British' Empire.

- Aurell, Martin (2003). L'Empire des Plantagenêt, 1154–1224. Perrin. p. 10. ISBN 9782262019853.

- Gerli, E. Michael; Armistead, Samuel G., eds. (2003). Medieval Iberia: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 9780415939188.

- Hallam, E.M. (1983). Capetian France 937–1328. Longman. p. 222. ISBN 9780582489103.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 5. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Aurell, Martin (2003). L'empire des Plantagenets. Perrin. p. 11. ISBN 9782262019853.

- Hallam, E.M. (1983). Capetian France 987–1328. Longman. p. 74. ISBN 9780582489103.

- Hallam, E.M. (1983). Capetian France 987–1328. Longman. p. 64. ISBN 9780582489103.

Then in 1151 Henry Plantagenet paid homage for the duchy to Louis VII in Paris, homage he repeated as king of England in 1156.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 50. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Penguin. pp. 226. ISBN 9780140148244.

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Penguin. pp. 91. ISBN 9780140148244.

But this absenteeism solidified rather than sapped royal government since it engendered structures both to maintain peace and extract money in the King's absence, money which was above all needed across the Channel.

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Penguin. pp. 215. ISBN 9780140148244.

- Duffy, Sean (2004). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 58, 59. ISBN 9780415940528.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 67. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Hallam, E.M. (1983). Capetian France 987–1328. Longman. p. 37. ISBN 9780582489103.

- Hallam, E.M. (1983). Capetian France 987–1328. Longman. p. 67. ISBN 9780582489103.

- Hallam, E.M. (1983). Capetian France 987–1328. Longman. p. 76. ISBN 9780582489103.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 24. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Norgate, Kate (1887). England under the Angevin Kings. London: Macmillan. pp. 388.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 60. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 58. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Moss, Vincent (1999). "The Norman fiscal revolution, 1193–98". In Ormrod, Mark; Bonney, Margaret; Bonney, Richard (eds.). Crises, Revolutions and Self-sustained Growth: Essays in European Fiscal History, 1130–1830. Paul Watkins Publishing. ISBN 9781871615937.

- Bolton, J.L. (1999). "The English economy in the early thirteenth century". In Church, S.D. (ed.). King John: New Interpretations. Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851157368.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 60. ISBN 9780713162493.

In 1198, for example, both Caen and Rouen had to find more money than London.

- Hallam, E.M. (1983). Capetian France 987–1328. Longman. p. 227. ISBN 9780582489103.

- Hallam, E.M. (1983). Capetian France 987–1328. Longman. p. 226. ISBN 9780582489103.

- Wheeler, Bonnie; Parsons, John Carmi, eds. (2002). Eleanor of Aquitaine: Lord and Lady. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780312295820.

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Penguin. pp. 163. ISBN 9780140148244.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 16. ISBN 9780713162493.

While Geoffrey held on the gains he had made in Normandy, in England Matilda was driven back almost to a square one.

- Hallam, E.M. (1983). Capetian France 987–1328. Longman. p. 158. ISBN 9780582489103.

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Penguin. pp. 192. ISBN 9780140148244.

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Penguin. pp. 193. ISBN 9780140148244.

Henry spent 43 per cent of his reign in Normandy, 20 per cent elsewhere in France (mostly in Anjou, Maine and Touraine) and only 37 per cent in Britain.

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Penguin. pp. 193. ISBN 9780140148244.

- Warren, W.L. (2000). Henry II. Yale University Press. p. 64. ISBN 9780300084740.

- Warren, W.L. (2000). Henry II. Yale University Press. pp. 71, 72. ISBN 9780300084740.

- "An Annotated Translation of the Life of St. Thomas Becket by William Fitzstephen", p. 40-41, accessed 8 January 2015.

- Powicke, F.M. (1913). The Loss of Normandy: 1189 – 1204 ; Studies in the History of the Angevin Empire. Manchester University Press. p. 182. ISBN 9780719057403.

- Warren, W.L. (2000). Henry II. Yale University Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780300084740.

- Nicholas, David (1992). Medieval Flanders. Longman. p. 71. ISBN 9780582016798.

- "(Cf. Davis, King Stephen, 18–20) At this time the future rival ports of Calais, Dunkirk, and Ostend were blocked by sandbanks, leaving Boulogne as one of the most important continental ports." – W.L. Warren, Henry II, p. 16.

- Warren, W.L. (2000). Henry II. Yale University Press. p. 224. ISBN 9780300084740.

- Anderson, James (1732). Royal Genealogies, Or the Genealogical Tables of Emperors, Kings and Princes. p. 619.

Hoel was disinherited and declar'd illegitimate by his Father's last will.

- Warren, W.L. (2000). Henry II. Yale University Press. p. 75. ISBN 9780300084740.

- Warren, W.L. (2000). Henry II. Yale University Press. p. 76. ISBN 9780300084740.

- Warren, W.L. (2000). Henry II. Yale University Press. pp. 76, 77. ISBN 9780300084740.

- Warren, W.L. (2000). Henry II. Yale University Press. p. 183. ISBN 9780300084740.

- Warren, W.L. (2000). Henry II. Yale University Press. p. 561. ISBN 9780300084740.

- Everard, J.A. (2006). Brittany and the Angevins: Province and Empire 1158–1203. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780521026925.

- Harper-Bill, Christopher; Vincent, Nicholas, eds. (2007). Henry II: New Interpretations. Boydell Press. p. 115. ISBN 9781843833406.

- Warren, W.L. (2000). Henry II. Yale University Press. pp. 100, 101. ISBN 9780300084740.

- Everard, J.A. (2000). Brittany and the Angevins: Province and Empire, 1158–1203. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–28. ISBN 9780521026925.

- Everard, J.A. (2000). Brittany and the Angevins: Province and Empire, 1158–1203. Cambridge University Press. pp. 28, 31. ISBN 9780521026925.

- Everard, J.A. (2000). Brittany and the Angevins – Province and Empire 1158–1203. Cambridge University Press. pp. 29–35. ISBN 9780521026925.

- Everard, J.A. (2000). Brittany and the Angevins – Province and Empire 1153–1203. Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780521026925.

- J.A. Everard states in Brittany and the Angevins – Province and Empire 1158–1203 p. 31 that "The duchy of Brittany was now recognised as forming part of the Angevin Empire".

- Duncan, A.A.M. (1975). Scotland, the Making of the Kingdom. Oliver & Boyd. p. 72. ISBN 9780050020371.

- Barrow, G.W.S. (1981). Kingship and Unity: Scotland, 1000–1306. University of Toronto Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780802064486.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 27. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 28. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Warren, W.L. (2000). Henry II. Yale University Press. p. 86. ISBN 9780300084740.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. pp. 29, 30. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. pp. 30, 31. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Hallam, E.M. (1983). Capetian France 987–1328. Longman. p. 162. ISBN 9780582489103.

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Penguin. pp. 203. ISBN 9780140148244.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 31. ISBN 0340741155.

- Gillingham, John (2000). Richard I. Yale University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0300094043.

- Hallam, E.M. (1983). Capetian France 987–1328. Longman. p. 164. ISBN 9780582489103.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 37. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. Hodder Arnold. p. 40. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Penguin. pp. 255. ISBN 9780140148244.

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Penguin. pp. 245. ISBN 9780140148244.

- F. Delaborde: "Recueil des actes de Philippe Auguste".

- Gillingham, John (2000). Richard I. Yale University Press. p. 142. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (1999). Richard I. Yale University Press. pp. 163, 164, 165, 166. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (1999). Richard I. Yale University Press. p. 229. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (1999). Richard I. Yale University Press. p. 230. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (1999). Richard I. Yale University Press. pp. 235, 236. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (1999). Richard I. Yale University Press. pp. 239, 240. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (1999). Richard I. Yale University Press. p. 240. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (1999). Richard I. Yale University Press. pp. 240, 241. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (1999). Richard I. Yale University Press. pp. 244, 245. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (1999). Richard I. Yale University Press. p. 246. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (1999). Richard I. Yale University Press. pp. 246, 247, 248, 249. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (2000). Richard I. Yale University Press. p. 251. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (2000). Richard I. p. 269. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (2000). Richard I. p. 272. ISBN 0300094043.

- Gillingham, John (2000). Richard I. p. 279. ISBN 0300094043.

- France, John (1999). "Commanders". Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades, 1000–1300. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801486074.

There were many successful warriors, notably William the Conqueror, but the greatest commander within this period was undoubtedly Richard I.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. London: Hodder Arnold. p. 48. ISBN 9780713162493.

- Warren, W.L. (1961). King John. Yale University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780300073744.

- Gillingham, John (1984). The Angevin Empire. London: Hodder Arnold. p. 86. ISBN 0340741155.

- Power, Daniel (2002). "Angevin Normandy". A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. p. 67. ISBN 9781843833413.

- Warren, W. L. (1961). King John. Yale University Press. pp. 49, 50. ISBN 9780300073744.