History of Macedonia (ancient kingdom)

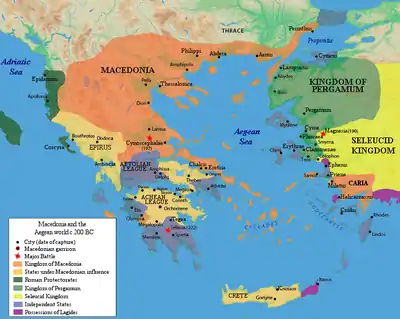

The kingdom of Macedonia was an ancient state in what is now the Macedonian region of northern Greece, founded in the mid-7th century BC during the period of Archaic Greece and lasting until the mid-2nd century BC. Led first by the Argead dynasty of kings, Macedonia became a vassal state of the Achaemenid Empire of ancient Persia during the reigns of Amyntas I of Macedon (r. 547 – 498 BC) and his son Alexander I of Macedon (r. 498 – 454 BC). The period of Achaemenid Macedonia came to an end in roughly 479 BC with the ultimate Greek victory against the second Persian invasion of Greece led by Xerxes I and the withdrawal of Persian forces from the European mainland.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Greece |

|

|

|

During the age of Classical Greece, Perdiccas II of Macedon (r. 454 – 413 BC) became directly involved in the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) between Classical Athens and Sparta, shifting his alliance from one city-state to another while attempting to retain Macedonian control over the Chalcidice peninsula. His reign was also marked by conflict and temporary alliances with the Thracian ruler Sitalces of the Odrysian Kingdom. He eventually made peace with Athens, which formed an alliance with Macedonia that carried over into the reign of Archelaus I of Macedon (r. 413 – 399 BC). His reign brought peace, stability, and financial security to the Macedonian realm, yet his little-understood assassination (perhaps by a royal page) left the kingdom in peril and conflict. The turbulent reign of Amyntas III of Macedon (r. 393 – 370 BC) witnessed devastating invasions by both the Illyrian ruler Bardylis of the Dardani and the Chalcidian city-state of Olynthos, both of which were defeated with the aid of foreign powers, the city-states of Thessaly and Sparta, respectively. Alexander II (r. 370 – 368 BC) invaded Thessaly but failed to hold Larissa, which was captured by Pelopidas of Thebes, who made peace with Macedonia on condition that they surrender noble hostages, including the future king Philip II of Macedon (r. 359 – 336 BC).

Philip II came to power when his older brother Perdiccas III of Macedon (r. 368 – 359 BC) was defeated and killed in battle by the forces of Bardylis. With the use of skillful diplomacy, Philip II was able to make peace with the Illyrians, Thracians, Paeonians, and Athenians who threatened his borders. This allowed him time to dramatically reform the Ancient Macedonian army, establishing the Macedonian phalanx that would prove crucial to his kingdom's success in subduing Greece, with the exception of Sparta. He gradually enhanced his political power by forming marriage alliances with foreign powers, destroying the Chalcidian League in the Olynthian War (349–348 BC), and becoming an elected member of the Thessalian and Amphictyonic Leagues for his role in defeating Phocis in the Third Sacred War (356–346 BC). After the Macedonian victory over a coalition led by Athens and Thebes at the 338 BC Battle of Chaeronea, Philip established the League of Corinth and was elected as its hegemon in anticipation of commanding a united Greek invasion of the Achaemenid Empire under Macedonian hegemony.[1][2][3] However, when Philip II was assassinated by one of his bodyguards, he was succeeded by his son Alexander III, better known as Alexander the Great (r. 336 – 323 BC), who invaded Achaemenid Egypt and Asia and toppled the rule of Darius III, who was forced to flee into Bactria (in what is now Afghanistan) where he was killed by one of his kinsmen, Bessus. This pretender to the throne was eventually executed by Alexander, yet the latter eventually succumbed to an unknown illness at the age of 32, whose death led to the Partition of Babylon by his former generals, the diadochi, chief among them being Antipater, regent of Alexander IV of Macedon (r. 323 – 309 BC). This event ushered in the Hellenistic period in West Asia and the Mediterranean world, leading to the formation of the Ptolemaic, Seleucid, and Attalid successor kingdoms in the former territories of Alexander's empire.

Macedonia continued its role as the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece, yet its authority became diminished due to civil wars between the Antipatrid and nascent Antigonid dynasty. After surviving crippling invasions by Pyrrhus of Epirus, Lysimachus, Seleucus I Nicator, and the Celtic Galatians, Macedonia under the leadership of Antigonus II of Macedon (r. 277 – 274 BC; 272–239 BC) was able to subdue Athens and defend against the naval onslaught of Ptolemaic Egypt in the Chremonidean War (267–261 BC). However, the rebellion of Aratus of Sicyon in 351 BC led to the formation of the Achaean League, which proved to be a perennial problem for the ambitions of the Macedonian kings in mainland Greece. Macedonian power saw a resurgence under Antigonus III Doson (r. 229 – 221 BC), who defeated the Spartans under Cleomenes III in the Cleomenean War (229–222 BC). Although Philip V of Macedon (r. 221 – 179 BC) managed to defeat the Aetolian League in the Social War (220–217 BC), his attempts to project Macedonian power into the Adriatic Sea and formation of a Macedonian–Carthaginian Treaty with Hannibal alarmed the Roman Republic, which convinced a coalition of Greek city-states to attack Macedonia while Rome focused on defeating Hannibal in Italy. Rome was ultimately victorious in the First (214–205 BC) and Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC) against Philip V, who was also defeated in the Cretan War (205–200 BC) by a coalition led by Rhodes. Macedonia was forced to relinquish its holdings in Greece outside of Macedonia proper, while the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC) succeeded in toppling the monarchy altogether, after which Rome placed Perseus of Macedon (r. 179 – 168 BC) under house arrest and established four client state republics in Macedonia. In an attempt to dissuade rebellion in Macedonia, Rome imposed stringent constitutions in these states that limited their economic growth and interactivity. However, Andriscus, a pretender to the throne claiming descent from the Antigonids, briefly revived the Macedonian monarchy during the Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BC). His forces were crushed at the second Battle of Pydna by the Roman general Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus, leading to the establishment of the Roman province of Macedonia and the initial period of Roman Greece.

Early history and legend

The Greek historians Herodotus and Thucydides reported the legend that the Macedonian kings of the Argead dynasty were descendants of Temenus of Argos, Peloponnese, who was believed to have had the mythical Heracles as one of his ancestors.[4] The legend states that three brothers and descendants of Temenus wandered from Illyria to Upper Macedonia, where a local king nearly had them killed and forced into exile due to an omen that the youngest, Perdiccas, would become king. The latter eventually obtained the title after settling near the alleged gardens of Midas next to Mount Bermius in Lower Macedonia.[4] Other legends, mentioned by the Roman historians Livy, Velleius and Justin and by the Greek biographer Plutarch and the Greek geographer Pausanias stated that Caranus of Macedon was the first Macedonian king and that he was succeeded by Perdiccas I.[5][6][7][8][9][10] Greeks of the Classical period generally accepted the origin story provided by Herodotus, or another involving lineage from Zeus, chief god of the Greek pantheon, lending credence to the idea that the Macedonian ruling house possessed the divine right of kings.[11] Herodotus wrote that Alexander I of Macedon (r. 498 – 454 BC) convinced the Hellanodikai authorities of the Ancient Olympic Games that his Argive lineage could be traced back to Temenus, and thus his perceived Greek identity permitted him to enter the Olympic competitions.[12]

Very little is known about the first five kings of Macedonia (or the first eight kings depending on which royal chronology is accepted).[13] There is much greater evidence for the reigns of Amyntas I of Macedon (r. 547 – 498 BC) and his successor Alexander I, especially due to the aid given by the latter to the Persian commander Mardonius at the Battle of Platea in 479 BC, during the Greco-Persian Wars.[14] Although stating that the first several kings listed by Herodotus were most likely legendary figures, historian Robert Malcolm Errington uses the rough estimate of twenty-five years for the reign of each of these kings to assume that the capital Aigai (modern Vergina) could have been under their rule since roughly the mid-7th century BC, during the Archaic period.[15]

The kingdom was situated in the fertile alluvial plain, watered by the rivers Haliacmon and Axius, called Lower Macedonia, north of Mount Olympus. Around the time of Alexander I, the Argead Macedonians started to expand into Upper Macedonia, lands inhabited by independent Greek tribes like the Lyncestae and the Elimiotae, and to the west, beyond the Axius river, into the Emathia, Eordaia, Bottiaea, Mygdonia, Crestonia and Almopia; regions settled by, among others, many Thracian tribes.[16] To the north of Macedonia lay various non-Greek peoples such as the Paeonians due north, the Thracians to the northeast, and the Illyrians, with whom the Macedonians were frequently in conflict, to the northwest.[17] To the south lay Thessaly, with whose inhabitants the Macedonians had much in common, both culturally and politically, while to the west lay Epirus, with whom the Macedonians had a peaceful relationship and in the 4th century BC formed an alliance against Illyrian raids.[18] Prior to the 4th century BC, the kingdom covered a region approximately corresponding to the western and central parts of the region of Macedonia in modern Greece.[19]

After Darius I of Persia (r. 522 – 486 BC) launched a military campaign against the Scythians in Europe in 513 BC, he left behind his general Megabazus to quell the Paeonians, Thracians, and coastal Greek city-states of the southern Balkans.[20] In 512/511 BC Megabazus sent envoys demanding Macedonian submission as a vassal state to the Achaemenid Empire of ancient Persia, to which Amyntas I responded by formally accepting the hegemony of the Persian king of kings.[21] This began the period of Achaemenid Macedonia, which lasted for roughly three decades. The Macedonian kingdom was largely autonomous and outside of Persian control, but was expected to provide troops and provisions for the Achaemenid army.[22] Amyntas II, son of Amyntas I's daughter Gygaea of Macedon and her husband Bubares, son of Megabazus, was given the Phrygian city of Alabanda as an appanage by Xerxes I (r. 486 – 465 BC), to secure the Persian-Macedonian marriage alliance.[23] Persian authority over Macedonia was interrupted by the Ionian Revolt (499–493 BC), yet the Persian general Mardonius was able to subjugate Macedonia, bringing it under Persian rule.[24] It is doubtful, though, that Macedonia was ever officially included within a Persian satrapy (i.e. province).[25] The Macedonian king Alexander I must have viewed his subordination as an opportunity to aggrandize his own position, since he used Persian military support to extend his own borders.[26] The Macedonians provided military aid to Xerxes I during the Second Persian invasion of Greece in 480–479 BC, which saw Macedonians and Persians fighting against a Greek coalition led by Athens and Sparta.[27] Following the Greek victory at Salamis, the Persians sent Alexander I as an envoy to Athens, hoping to strike an alliance with their erstwhile foe, yet his diplomatic mission was rebuffed.[28] Achaemenid control over Macedonia ceased when the Persians were ultimately defeated by the Greeks and fled the Greek mainland in Europe.[29]

Involvement in the Classical Greek world

Alexander I, who Herodotus claimed was entitled proxenos and euergetes ('benefactor') by the Athenians, cultivated a close relationship with the Greeks following the Persian defeat and withdrawal, sponsoring the erection of statues at both major panhellenic sanctuaries at Delphi and Olympia.[30] After his death in 454 BC, he was granted the posthumous title Alexander I 'the Philhellene' ('friend of the Greeks'), perhaps designated by later Hellenistic Alexandrian scholars, most certainly preserved by the Greco-Roman historian Dio Chrysostom, and most likely influenced by Macedonian propaganda of the 4th century BC that emphasized the positive role the ancestors of Philip II (r. 359 – 336 BC) had in Greek affairs.[31] Alexander I's successor Perdicas II (r. 454 – 413 BC) was not only saddled with internal revolt by the petty kings of Upper Macedonia, but also faced serious challenges to Macedonian territorial integrity by Sitalces, a ruler in Thrace, and the Athenians, who fought four separate wars against Macedonia under Perdiccas II.[32] During his reign, Athenian settlers began to encroach upon his coastal territories in Lower Macedonia to gather resources such as timber and pitch in support of their navy, a practice that was actively encouraged by the Athenian leader Pericles when he had colonists settle among the Bisaltae along the Strymon River.[33] From 476 BC onward, the Athenians coerced some of the coastal towns of Macedonia along the Aegean Sea to join the Athenian-led Delian League as tributary states and in 437/436 BC founded the city of Amphipolis at the mouth of the Strymon River for access to timber as well as gold and silver from the Pangaion Hills.[34]

War broke out in 433 BC when Athens, perhaps seeking additional cavalry and resources in anticipation of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), allied with a brother and cousin of Perdiccas II who were in open rebellion against him.[35] This led Perdiccas to seek alliances with Athens' rivals Sparta and Corinth, yet when his efforts were rejected he instead promoted the rebellion of nearby nominal Athenian allies in Chalcidice, winning over the important city of Potidaea.[36] Athens responded by sending a naval invasion force that captured Therma and laid siege to Pydna.[37] However, they were unsuccessful in retaking Chalcidice and Potidaea due to stretching their forces thin by fighting the Macedonians and their allies on multiple fronts, and therefore sued for peace with Macedonia.[37] War resumed shortly after with the Athenian capture of Beroea and Macedonian aid given to the Potidaeans during an Athenian siege, yet by 431 BC, the Athenians and Macedonians concluded a peace treaty and alliance orchestrated by the Thracian ruler Sitalces of the Odrysian kingdom.[38] The Athenians had hoped to use Sitalces against the Macedonians, but due to Sitalces' desire to focus on acquiring more Thracian allies, he convinced Athens to make peace with Macedonia on the condition that he provide cavalry and peltasts for the Athenian army in Chalcidice.[39] Under this arrangement, Perdiccas II was given back Therma and no longer had to contend with his rebellious brother, Athens, and Sitacles all at once; in exchange he aided the Athenians in their subjugation of settlements in Chalcidice.[40]

In 429 BC, Perdiccas II sent aid to the Spartan commander Cnemus in Acarnania, but the Macedonian forces arrived too late to enter the Battle of Naupactus, which ended in an Athenian victory.[41] In that same year, Sitalces, according to Thucydides, invaded Macedonia at the behest of Athens to aid them in subduing Chalcidice and to punish Perdiccas II for violating the terms of their peace treaty.[42] However, given Sitalces' huge Thracian invading force (allegedly 150,000 soldiers) and a nephew of Perdiccas II that he intended to place on the Macedonian throne after toppling the latter's regime, Athens must have become wary of acting on their supposed alliance since they failed to provide him with promised naval support.[43] Sitalces eventually retreated from Macedonia, perhaps due to logistical concerns: a shortage of provisions and harsh winter conditions.[44]

In 424 BC, Perdiccas began to play a prominent role in the Peloponnesian War by aiding the Spartan general Brasidas in convincing Athenian allies in Thrace to defect and ally with Sparta.[45] After failing to convince Perdiccas II to make peace with Arrhabaeus of Lynkestis (a small region of Upper Macedonia), Brasidas agreed to aid the Macedonian fight against Arrhabaeus, although he expressed his concerns about leaving his Chalcidian allies to their own devices against Athens, as well as the fearsome Illyrian reinforcements arriving on the side of Arrhabaeus.[46] The massive combined force commanded by Arrhabaeus apparently caused the army of Perdiccas II to flee in haste before the battle began, which enraged the Spartans under Brasidas, who proceeded to snatch pieces of the Macedonian baggage train left unprotected.[47] Subsequently, Perdiccas II not only made peace with Athens but switched sides, blocking Peloponnesian reinforcements from reaching Brasidas via Thessaly.[48] The treaty offered Athens economic concessions, but it also guaranteed internal stability in Macedonia since Arrhabaeus and other domestic detractors were convinced to lay down their arms and accept Perdiccas II as their suzerain lord.[49]

Perdiccas II was obliged to send aid to the Athenian general Cleon, but he and Brasidas died in 422 BC, and the Peace of Nicias struck in the following year between Athens and Sparta nullified the Macedonian king's responsibilities as an erstwhile Athenian ally.[50] After the Battle of Mantinea in 418 BC, Sparta and Argos formed a new alliance, which, alongside the threat of neighboring poleis in Chalcidice who were aligned with Sparta, induced Perdiccas II to abandon his Athenian alliance in favor of Sparta once again.[51] This proved to be a strategic error, since Argos quickly switched sides as a pro-Athenian democracy, allowing Athens to punish Macedonia with a naval blockade in 417 BC along with the resumption of military activity in Chalcidice.[52] Perdiccas II agreed to a peace settlement and alliance with Athens once more in 414 BC and, on his death a year later, was succeeded by his son Archelaus I (r. 413 – 399 BC).[53]

Archelaus I maintained good relations with Athens throughout his reign, relying on Athens to provide naval support in his 410 BC siege of Pydna, and in exchange providing Athens with timber and naval equipment.[54] With improvements to military organization and building of new infrastructure such as fortresses, Archelaus was able to strengthen Macedonia and project his power into Thessaly, where he aided his allies; yet he faced some internal revolt as well as problems fending off Illyrian incursions led by Sirras.[55] Although he retained Aigai as a ceremonial and religious center, Archelaus I moved the capital of the kingdom north to Pella, which was then positioned by a lake with a river connecting it to the Aegean Sea.[56] He improved Macedonia's currency by minting coins with a higher silver content as well as issuing separate copper coinage.[57] His royal court attracted the presence of well-known intellectuals such as the Athenian playwright Euripides.[58]

Historical sources offer wildly different and confused accounts as to who assassinated Archelaus I, although it likely involved a homosexual love affair with royal pages at his court.[59] What ensued was a power struggle lasting from 399 to 393 BC of four different monarchs claiming the throne: Orestes, son of Archelaus I; Aeropus II, uncle, regent, and murderer of Orestes; Pausanias, son of Aeropus II; and Amyntas II, who was married to the youngest daughter of Archelaus I.[60] Very little is known about this period, although each of these monarchs aside from Orestes managed to mint debased currency imitating that of Archelaus I.[61] Finally, Amyntas III (r. 393 – 370 BC), son of Arrhidaeus and grandson of Amyntas , one of the sons of Alexander I, to the throne by killing Pausanias.[60]

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus provided a seemingly conflicting account about Illyrian invasions occurring in 393 BC and 383 BC, which may have been representative of a single invasion led by Bardylis of the Dardani.[62] In this event, Amyntas III is said to have fled his own kingdom and returned with the support of Thessalian allies, while a possible pretender to the throne named Argaeus had ruled temporarily in Amyntas III's absence.[63] When the powerful Chalcidian city of Olynthos was allegedly poised to overthrow Amyntas III and conquer the Macedonian kingdom, Teleutias, brother of the Spartan king Agesilaus II, sailed to Macedonia with a large Spartan force to provide critical aid to Amyntas III.[64] The result of this campaign in 379 BC was the surrender of Olynthos and the abolition of the Chalcidian League.[65]

Amyntas III had children with two wives, but it was his eldest son by his marriage with Eurydice I who succeeded him as Alexander II (r. 370 – 368 BC).[66] When Alexander II invaded Thessaly and occupied Larissa and Crannon as a challenge to the suzerainty of the tagus (supreme Thessalian military leader) Alexander of Pherae, the Thessalians appealed to Pelopidas of Thebes for help to expel both of these rival overlords.[67] After Pelopidas captured Larissa, Alexander II made peace and allied with Thebes, handing over noble hostages including his brother and future king, Philip II.[68] Afterwards, Ptolemy of Aloros assassinated his brother-in-law Alexander II and acted as regent for the latter's younger brother Perdiccas III (r. 368 – 359 BC).[69] Ptolemy's intervention in Thessaly in 367 BC provoked another Theban invasion by Pelopidas, who was undermined when Ptolemy bribed his mercenaries not to fight, thus leading to a newly proposed alliance between Macedonia and Thebes, but only on the condition that more hostages, including one of his Ptolemy's sons, were to be handed over to Thebes.[70] By 365 BC, Perdiccas III had reached the age of majority and took the opportunity to kill his regent Ptolemy, initiating a sole reign marked by internal stability, financial recovery, fostering of Greek intellectualism at his court, and the return of his brother Philip from Thebes.[70] However, Perdiccas III also dealt with an Athenian invasion by Timotheus, son of Conon, that led to the loss of Methone and Pydna, while an invasion of Illyrians led by Bardylis succeeded in killing Perdiccas III and 4,000 Macedonian troops in battle.[71]

Rise of Macedon

Right: another bust of Philip II, a 1st-century AD Roman copy of a Hellenistic Greek original, now in the Vatican Museums

Philip II of Macedon (r. 359 – 336 BC), who spent much of his adolescence as a political hostage in Thebes, was twenty-four years old when he acceded to the throne and immediately faced crises that threatened to topple his leadership.[72] However, with the use of deft diplomacy, he was able to convince the Thracians under Berisades to cease their support of Pausanias, a pretender to the throne, and the Athenians to halt their backing of another pretender named Arg(a)eus (perhaps the same who had caused trouble for Amyntas III).[73] He achieved these by bribing the Thracians and their Paeonian allies and removing a garrison of Macedonian troops from Amphipolis, establishing a treaty with Athens that relinquished his claims to that city.[74] He was also able to make peace with the Illyrians who had threatened his borders.[75]

.svg.png.webp)

The exact date in which Philip II initiated reforms to radically transform the Macedonian army's organization, equipment, and training is unknown, including the formation of the Macedonian phalanx armed with long pikes (i.e. the sarissa). The reforms took place over a period of several years and proved immediately successful against his Illyrian and Paeonian enemies.[76] Confusing accounts in ancient sources have led modern scholars to debate how much Philip II's royal predecessors may have contributed to these military reforms. It is perhaps more likely that his years of captivity in Thebes during the Theban hegemony influenced his ideas, especially after meeting with the renowned general Epaminondas.[77]

Although Macedonia and the rest of Greece traditionally practiced monogamy in marriage, Philip II divulged in the 'barbarian' practice of polygamy, marrying seven different wives with perhaps only one that didn't involve the loyalty of his aristocratic subjects or the affirmation of a new alliance.[78] For instance, his first marriages were to Phila of Elimeia of the Upper Macedonian aristocracy as well as the Illyrian princess Audata, granddaughter(?) of Bardylis, to ensure a marriage alliance with their people.[79] To establish an alliance with Larissa in Thessaly, he married the Thessalian noblewoman Philinna in 358 BC, who bore him a son who would later rule as Philip III Arrhidaeus (r. 323 – 317 BC).[80] In 357 BC, he married Olympias in order to secure an alliance with Arybbas, the King of Epirus and the Molossians. This marriage would bear a son who would later rule as Alexander III (better known as Alexander the Great) and claim descent from the legendary Achilles by way of his dynastic heritage from Epirus.[81] It has been argued whether or not the Achaemenid Persian kings influenced Philip's practice of polygamy, although it seems to have been practiced by Amyntas III who had three sons with a possible second wife Gygaea: Archelaus, Arrhidaeus, and Menelaus.[82] Philip II had Archelaus put to death in 359 BC, while Philip's other two half brothers fled to Olynthos, serving as a casus belli for the Olynthian War (349–348 BC) against the Chalcidian League.[83]

While Athens was preoccupied with the Social War (357–355 BC), Philip took this opportunity to retake Amphipolis in 357 BC, for which the Athenians later declared war on him, and by 356 BC, recaptured Pydna and Potidaea, the latter of which he handed over to the Chalcidian League as promised in a treaty of 357/356 BC.[84] In this year, he was also able to take Crenides, later refounded as Philippi and providing much wealth in gold, while his general Parmenion was victorious against the Illyrian king Grabos of the Grabaei.[85] During the siege of Methone from 355 to 354 BC, Philip lost his right eye to an arrow wound, but was able to capture the city and was even cordial to the defeated inhabitants (unlike the Potidaeans, who had been sold into slavery).[86]

It was at this stage when Philip II involved Macedonia in the Third Sacred War (356–346 BC). The conflict began when Phocis captured and plundered the temple of Apollo at Delphi as a response to Thebes' demand that they submit unpaid fines, causing the Amphictyonic League to declare war on Phocis and a civil war among the members of the Thessalian League aligned with either Phocis or Thebes.[87] Philip II's initial campaign against Pherae in Thessaly in 353 BC at the behest of Larissa ended in two disastrous defeats by the Phocian general Onomarchus.[88] However, he returned the following year and defeated Onomarchus at the Battle of Crocus Field, which led to his election as leader (archon) of the Thessalian League, ability to recruit Thessalian cavalry, provided him a seat on the Amphictyonic Council and a marriage alliance with Pherae by wedding Nicesipolis, niece of the tyrant Jason of Pherae.[89]

After campaigning against the Thracian ruler Cersobleptes, Philip II began his war against the Chalcidian League in 349 BC, which had been reestablished in 375 BC following a temporary disbandment.[90] Despite an Athenian intervention by Charidemus,[91] Olynthos was captured by Philip II in 348 BC, whereupon he sold its inhabitants into slavery, bringing back some Athenian citizens to Macedonia as slaves as well.[92] The Athenians, especially in a series of speeches by Demosthenes known as the Olynthiacs, were unsuccessful in persuading their allies to counterattack, so in 346 BC, they concluded a treaty with Macedonia known as the Peace of Philocrates.[93] The treaty stipulated that Athens would relinquish claims to Macedonian coastal territories, the Chalcidice, and Amphipolis in return for the release of the enslaved Athenians as well as guarantees that Philip would not attack Athenian settlements in the Thracian Chersonese.[94] Meanwhile, Phocis and Thermopylae were captured, the Delphic temple robbers executed, and Philip II was awarded the two Phocian seats on the Amphictyonic Council as well as the position of master of ceremonies over the Pythian Games.[95] Athens initially opposed his membership on the council and refused to attend the games in protest, but they were eventually swayed to accept these conditions, partially due to the oration On the Peace by Demosthenes.[96]

For the next few years Philip II was occupied with reorganizing the administrative system of Thessaly, campaigning against the Illyrian ruler Pleuratus I, deposing Arybbas in Epirus in favor of his brother-in-law Alexander I (through Philip II's marriage with Olympias), and defeating Cersebleptes in Thrace. This allowed him to extend Macedonian control over the Hellespont in anticipation of an invasion into Achaemenid Asia.[97] In what is now Bulgaria, Philip II conquered the Thracian city of Panegyreis in 342 BC and reestablished it as Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv, Roman-era Trimontium).[98] War broke out with Athens in 340 BC while Philip II was engaged in two ultimately unsuccessful sieges of Perinthus and Byzantion, followed by a successful campaign against the Scythians along the Danube and Macedonia's involvement in the Fourth Sacred War against Amphissa in 339 BC.[99] Hostilities between Thebes and Macedonia began when Thebes ousted a Macedonian garrison from Nicaea (near Thermopylae), leading Thebes to join Athens, Megara, Corinth, Achaea, and Euboea in a final confrontation against Macedonia at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC.[100] The Athenian oligarch Philippides of Paiania was instrumental in the Macedonian victory at Chaeronea by assisting Philip II's cause, but was later prosecuted in Athens as a traitor by the orator and statesman Hypereides.[101]

After the Macedonian victory at Chaeronea, Philip II imposed harsh conditions on Thebes, installing an oligarchy there, yet was lenient to Athens due to his desire to utilize their navy in a planned invasion of the Achaemenid Empire.[102] He was then chiefly responsible for the formation of the League of Corinth that included the major Greek city-states minus Sparta, being elected as the leader (hegemon) of its council (synedrion) by the spring of 337 BC despite the Kingdom of Macedonia being excluded as an official member of the league.[103] The Panhellenic fear of another Persian invasion of Greece perhaps contributed to Philip II's decision to invade the Achaemenid Empire.[104] The Persian aid offered to Perinthus and Byzantion in 341–340 BC highlighted Macedonia's strategic need to secure Thrace and the Aegean Sea against increasing Achaemenid encroachment, as Artaxerxes III further consolidated his control over satrapies in western Anatolia.[105] The latter region, yielding far more wealth and valuable resources than the Balkans, was also coveted by the Macedonian king for its sheer economic potential.[106]

.jpg.webp)

After his election by the League of Corinth as their commander-in-chief (strategos autokrator) of a forthcoming campaign to invade the Achaemenid Empire, Philip II sought to shore up further Macedonian support by marrying Cleopatra Eurydice, niece of general Attalus.[108] Yet talk of providing new potential heirs infuriated Philip II's son Alexander (already a veteran of the Battle of Chaeronea) and his mother Olympias, who fled together to Epirus before Alexander was recalled to Pella.[108] Further tensions arose when Philip II offered his son Arrhidaeus's hand in marriage to Ada of Caria, daughter of Pixodarus, the Persian satrap of Caria. When Alexander intervened and proposed to marry Ada instead, Philip cancelled the wedding arrangements altogether and exiled Alexander's advisors Ptolemy, Nearchus, and Harpalus.[109] To reconcile with Olympias, Philip II had their daughter Cleopatra marry Olympias' brother (and Cleopatra's uncle) Alexander I of Epirus, yet Philip II was assassinated by his bodyguard Pausanias of Orestis during their wedding feast and succeeded by Alexander.[110]

Empire

Right: Bust of Alexander the Great, a Roman copy of the Imperial Era (1st or 2nd century AD) after an original bronze sculpture made by the Greek sculptor Lysippos, Louvre, Paris

Before Philip II was assassinated in the summer of 336 BC, relations with his son Alexander had degenerated to the point where he excluded him entirely from his planned invasion of Asia, choosing instead for him to act as regent of Greece and deputy hegemon of the League of Corinth.[111] This, alongside his mother Olympias' apparent concern over Philip II bearing another potential heir with his new wife Cleopatra Eurydice, have led scholars to wrangle over the idea of her and Alexander's possible roles in Philip's murder.[112] Nonetheless, Alexander III (r. 336 – 323 BC) was immediately proclaimed king by an assembly of the army and leading aristocrats, chief among them being Antipater and Parmenion.[113] By the end of his reign and military career in 323 BC, Alexander would rule over an empire consisting of mainland Greece, Asia Minor, the Levant, ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, and much of Central and South Asia (i.e. modern Pakistan).[114] His first pressing concerns, however, would be to bury his father at Aigai and to pursue a campaign of suppression closer to home in the Balkans.[115] Following Philip's death, the members of the League of Corinth revolted, yet were soon quelled by military force alongside persuasive diplomacy, Alexander forcing them to rejoin the league and elect him as hegemon to carry out the planned invasion of Achaemenid Persia.[116] Alexander also took the opportunity to settle the score he had with his rival Attalus (who had taunted him during the wedding feast of his daughter Cleopatra Eurydice and Philip II) by having him executed.[117]

In 335 BC, Alexander led a campaign against the Thracian tribe of the Triballi at Haemus Mons, fighting them along the Danube and forcing their surrender on Peuce Island.[118] Shortly thereafter, the Illyrian king Cleitus of the Dardani threatened to attack Macedonia, yet Alexander took the initiative and besieged them at Pelion (in modern Albania).[119] When Alexander was given news that Thebes had once again revolted from the League of Corinth and were besieging the Macedonian garrison in the Cadmea, Alexander left the Illyrian front and marched to Thebes, which he placed under siege.[120] After breaching the walls, Alexander's forces killed 6,000 Thebans, took 30,000 inhabitants as prisoners of war, and burned the city to the ground as a warning to others, which proved effective since no other Greek state aside from Sparta dared to challenge Alexander for the remainder of his reign.[121]

Throughout his military career and kingship, Alexander won every battle that he personally commanded.[122] His first victory against the Persians in Asia Minor at the Battle of the Granicus in 334 BC utilized a small cavalry contingent that successfully distracted the Persians, allowed his infantry to cross the river, and his Companions to drive them from the battle with a cavalry charge.[123] Following the tradition of Macedonian warrior kings, Alexander personally led the cavalry charge at the Battle of Issus in 333 BC, forcing the Persian king Darius III and his army to flee.[123] Darius III, despite having superior numbers, was again forced to flee the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC.[123] The Persian king was later captured and executed by his own satrap of Bactria and kinsman, Bessus, in 330 BC. The Macedonian king subsequently hunted down and executed Bessus in what is now Afghanistan, securing the region of Sogdia in the process.[124] At the 326 BC Battle of the Hydaspes (modern-day Punjab), when the war elephants of King Porus of the Pauravas threatened Alexander's troops, he had them form open ranks to surround the elephants and dislodge their handlers by using their sarissa pikes.[125] When his Macedonian troops threatened mutiny at Opis, Babylonia (near modern Baghdad, Iraq) in 324 BC, Alexander III offered Macedonian military titles and greater responsibilities to Persian officers and units instead, forcing his troops to seek forgiveness, which the king offered at a banquet urging reconciliation between Persians and Macedonians.[126]

Despite his skills as a commander, Alexander perhaps undercut his own rule by demonstrating signs of megalomania.[127] While utilizing effective propaganda such as the cutting of the Gordian Knot, he also attempted to portray himself as a living god and son of Zeus following his visit to the oracle at Siwah in the Libyan Desert (in modern-day Egypt) in 331 BC.[128] When he attempted to have his men prostrate before him at Bactra in 327 BC in an act of proskynesis (borrowed from the Persian kings), the Macedonians and Greeks considered this blasphemy and usurpation of the authority of the gods. Alexander's court historian Callisthenes refused to perform this ritual there and the others took his example, an act of protest that led Alexander to abandon the practice.[127] When Alexander had Parmenion murdered at Ecbatana in 330 BC, this was "symptomatic of the growing gulf between the king's interests and those of his country and people," according to Errington.[129] His murder of Cleitus the Black in 328 BC is described as "vengeful and reckless" by Dawn L. Gilley and Ian Worthington.[130] He also pursued the polygamous habits of his father Philip II and encouraged his men to marry native women in Asia, leading by example when he wed Roxana, a Sogdian princess of Bactria.[131] He then married Stateira II, eldest daughter of Darius III, and Parysatis II, youngest daughter of Artaxerxes III, at the Susa weddings in 324 BC.[132]

Meanwhile, in Greece the only disturbance to Macedonian rule was the attempt by the Spartan king Agis III to lead a rebellion of the Greeks against the Macedonians.[133] However, he was defeated in 331 BC at the Battle of Megalopolis by Antipater, who was serving as regent of Macedonia and deputy hegemon of the League of Corinth in Alexander's stead.[134] Although the governor of Thrace, Memnon, had threatened to rebel, it appears that Antipater dissuaded him with diplomacy before campaigning against Agis III in the Peloponnese.[135] Antipater deferred the punishment of Sparta to the League of Corinth headed by Alexander, who ultimately pardoned the Spartans on the condition that they submit fifty nobles as hostages.[136] Antipater's hegemony was somewhat unpopular in Greece due to his practice of exiling malcontents and garrisoning cities with Macedonian troops, yet in 330 BC, Alexander declared that the tyrannies installed in Greece were to be abolished and Greek freedom restored (despite the possibility that the Macedonian king most likely had Antipater install them in the first place).[137]

When Alexander the Great died at Babylon in 323 BC, his mother Olympias immediately accused Antipater and his faction with poisoning him, although there is no evidence to confirm this.[138] With no official heir apparent, the loyalties of the Macedonian military command became split between one side proclaiming Alexander's half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus (r. 323 – 317 BC) as king and another siding with Alexander's infant son with Roxana, Alexander IV (r. 323 – 309 BC).[139] Except for the Euboeans and Boeotians, the Greeks also immediately rose up in a rebellion against Antipater known as the Lamian War (323–322 BC).[140] When Antipater was defeated at the 323 BC Battle of Thermopylae, he fled to Lamia where he was besieged by the Athenian commander Leosthenes. Leonnatus rescued Antipater by lifting the siege.[141] Although Antipater ultimately subdued the rebellion, he died in 319 BC and left a vacuum of power wherein the two proclaimed kings of Macedonia became pawns in a power struggle between the diadochi, the former generals of Alexander's army who were now carving up his empire.[142]

A council of the army convened immediately after Alexander's death in Babylon, naming Philip III as king and the chiliarch Perdiccas as his regent.[143] However, Antipater, Antigonus Monophthalmus, Craterus, and Ptolemy, concerned about Perdiccas' increasing signs of self-aggrandizement, formed a coalition against him in open civil war that began with Ptolemy's seizure of the hearse of Alexander the Great.[144] When Perdiccas invaded Egypt in the summer of 321 BC to assault Ptolemy, he marched along the Nile River where 2,000 of his men drowned, leading the officers under his command to conspire against him and assassinate him.[145] Although Eumenes of Cardia managed to kill Craterus in battle, this had no grand effect on the course of events now that the victorious coalition convened in Syria to settle the issue of a new regency and territorial rights in the 321 BC Partition of Triparadisus.[146] The council appointed Antipater as regent over the two kings, after which Antipater delegated authority to the leading generals. However, before Antipater died in 319 BC, he named the staunch Argead loyalist Polyperchon as the regent to succeed him, passing over his own son Cassander, ignoring the right of the king to choose a regent (since Philip III was considered mentally unstable), and bypassing the council of the army as well.[147]

Forming an alliance with Ptolemy, Antigonus, and Lysimachus, Cassander had his officer Nicanor capture the Munichia fortress of Athens' port town Piraeus in defiance of Polyperchon's decree that Greek cities should be free of Macedonian garrisons, sparking the Second War of the Diadochi (319–315 BC).[148] Given a string of military failures by Polyperchon, in 317 BC Philip III, by way of his politically-engaged wife Eurydice II of Macedon, officially replaced him as regent with Cassander.[149] Afterwards Polyperchon desperately sought the aid of Olympias, mother of Alexander III who still resided in Epirus.[149] A joint force of Epirotes, Aetolians, and Polyperchon's troops invaded Macedonia and forced the surrender of Philip III and Eurydice's army, allowing Olympias to execute the king and force his queen to commit suicide.[150] Olympias then had Nicanor killed along with dozens of leading Macedonian nobles, yet by the spring of 316 BC Cassander defeated her forces, captured her, and placed her on trial for murder before sentencing her to death.[151]

Cassander married Philip II's daughter Thessalonike, inducting him into the Argead dynastic house, and briefly extended Macedonian control into Illyria as far as Epidamnos, although by 313 BC, it was retaken by the Illyrian king Glaucias of Taulantii.[152] By 316 BC, Antigonus had taken the territory of Eumenes and managed to eject Seleucus Nicator from his satrapy of Babylonia; in reaction to this a coalition of Cassander, Ptolemy, and Lysimachus issued an ultimatum to Antigonus in 315 BC for him to surrender various territories in Asia.[153] Antigonus promptly allied with Polyperchon, now based in Corinth, and issued an ultimatum of his own to Cassander, charging him with murder for executing Olympias and demanding that he hand over the royal family, king Alexander IV and the queen mother Roxana.[154] The conflict that followed lasted until the winter of 312/311 BC, when a new peace settlement recognized Cassander as general of Europe, Antigonus as 'first in Asia', Ptolemy as general of Egypt, and Lysimachus as general of Thrace.[155] Cassander had Alexander IV and Roxana put to death in the winter of 311/310 BC, had Heracles of Macedon executed in 309 BC as part of a peace settlement with Polyperchon, and by 306–305 BC the diadochi were declared kings of their respective territories.[156]

Hellenistic era

The beginning of Hellenistic Greece was defined by the struggle between the Antipatrid dynasty, led first by Cassander (r. 305 – 297 BC), son of Antipater, and the Antigonid dynasty, led by Antigonus I Monophthalmus (r. 306 – 301 BC) and his son, the future king Demetrius I of Macedon (r. 294 – 288 BC). While Cassander was besieging Athens in 303 BC, Demetrius invaded Boeotia in order to sever Cassander's path of retreat back to Macedonia, although Cassander managed to hastily abandon the siege and march back to Macedonia.[157] While Antigonus and Demetrius attempted to recreate Philip II's Hellenic league with themselves as dual hegemons, a revived coalition of Cassander, Ptolemy I Soter (r. 305 – 283 BC) of Egypt's Ptolemaic dynasty, Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305 – 281 BC) of the Seleucid Empire, and Lysimachus (r. 306 – 281 BC), King of Thrace decisively defeated the Antigonids at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, killing Antigonus and forcing Demetrius into flight.[158]

Cassander died in 297 BC and his sickly son Philip IV of Macedon died the same year, being succeeded by Cassander's other sons Alexander V of Macedon (r. 297 – 294 BC) and Antipater II of Macedon (r. 297 – 294 BC), with their mother Thessalonike of Macedon acting as regent.[159] While Demetrius fought against the Antipatrid forces in Greece, Antipater II killed his own mother and regent to obtain power.[159] His desperate brother Alexander V then requested aid from Pyrrhus of Epirus (r. 297 – 272 BC),[159] who had fought alongside Demetrius at the Battle of Ipsus, yet spent time as a hostage in Egypt as stipulated in an alliance treaty between Demetrius and Ptolemy I.[160] In exchange for defeating the forces of Antipater II and forcing him to flee to the court of Lysimachus in Thrace, Pyrrhus was awarded the westernmost portions of the Macedonian kingdom.[161] Demetrius marched north and invited his nephew Alexander V into his camp for a banquet on friendly pretenses, yet had him assassinated as he attempted to leave. Demetrius was then proclaimed king in Macedonia, yet his subjects became increasingly concerned by his conduct as a seemingly aloof monarch and Eastern-style autocrat.[159]

War broke out between Pyrrhus and Demetrius in 290 BC when Lanassa, wife of Pyrrhus, daughter of Agathocles of Syracuse, left him for Demetrius and offered him her dowry of Corcyra.[162] The war dragged on until 288 BC, when Demetrius lost the support of the Macedonians and fled the country. Macedonia was then divided between Pyrrhus and Lysimachus, the former taking western Macedonia and the latter eastern Macedonia.[162]

By 286 BC, Lysimachus was able to expel Pyrrhus and his forces from Macedonia altogether, yet in 282 BC, a new war erupted between Lysimachus and Seleucus I.[163] The conflict came to a head at the Battle of Corupedion where Lysimachus was killed, allowing Seleucus I to claim both Thrace and Macedonia.[164] In yet another reversal of fortunes, Seleucus I was then assassinated in 281 BC by his officer Ptolemy Keraunos, son of Ptolemy I and grandson of Antipater, who was then proclaimed king of Macedonia.[164] There was little respite from the political chaos in Macedonia, though, since Ptolemy Keraunos was killed in battle in 279 BC by Celtic invaders in the Gallic invasion of Greece.[165] The Macedonian army proclaimed the general Sosthenes of Macedon as king, although he apparently refused the title.[166] After defeating the Gallic ruler Bolgios and driving out the raiding party of Brennus, Sosthenes died and left a chaotic situation in Macedonia.[167] The Gallic warbands ravaged Macedonia until the arrival of Antigonus Gonatas, son of Demetrius, who defeated them in Thrace at the Battle of Lysimachia in 277 BC. He was then proclaimed king Antigonus II of Macedon (r. 277 – 274 BC, 272 – 239 BC).[168]

Beginning in 280 BC, Pyrrhus embarked on a campaign in Magna Graecia (i.e. southern Italy) against the Roman Republic known as the Pyrrhic War, followed by his invasion of Sicily.[169] Ptolemy Keraunos had secured his position on the Macedonian throne by gifting Pyrrhus five-thousand soldiers and twenty war elephants for this endeavor.[160] Pyrrhus returned to Epirus in 275 BC after the stalemate and ultimate failure of both campaigns, which contributed to the rise of Rome now that Greek cities in southern Italy such as Tarentum became Roman allies.[169] Despite having a depleted treasury, Pyrrhus decided to invade Macedonia in 274 BC, due to the perceived political instability of Antigonus II's regime. After defeating the largely mercenary army of Antigonus II at the 274 BC Battle of Aous, Pyrrhus was able to drive him out of Macedonia and force him to take refuge with his naval fleet.[170]

Pyrrhus lost much of his support among the Macedonians in 273 BC when his unruly Gallic mercenaries plundered the royal cemetery of Aigai.[171] Pyrrhus pursued Antigonus II in Greece, yet while he was occupied with the war in the Peloponnese, Antigonus II was able to recapture Macedonia.[172] While battling for control over Argos in 272 BC, Pyrrhus was killed while fighting in the city's streets, allowing Antigonus II to reclaim Greece as well.[173] He then restored the Argead dynastic graves at Aigai by constructing a massive tumulus.[174] Antigonus II also secured the Illyrian front and annexed Paeonia.[172]

The Antigonid naval fleets docked at Corinth and Chalkis during the reign of Antigonus II also proved instrumental in the maintenance of Antigonid-imposed local regimes in various Greek cities.[175] However, the Aetolian League proved to be a perennial problem for Antigonus II's ambitions in controlling central Greece, while the formation of the Achaean League in 251 BC pushed Macedonian forces out of much of the Peloponnese and at times incorporated Athens and Sparta.[176] While the Seleucid Empire aligned with Antigonid Macedonia during the Syrian Wars against Ptolemaic Egypt, the latter used its powerful navy to disrupt Antigonus II's efforts in controlling mainland Greece.[177] With the aid of the Ptolemaic navy, the Athenian statesman Chremonides led a revolt against Macedonian authority known as the Chremonidean War (267–261 BC).[178] However, by 265 BC, Athens was surrounded and besieged by Antigonus II's forces, a Ptolemaic fleet was defeated in the Battle of Cos, and Athens finally surrendered in 261 BC.[179] After Macedonia formed an alliance with the Seleucid ruler Antiochus II, a peace settlement between Antigonus II and Ptolemy II Philadelphus of Egypt was finally struck in 255 BC.[180]

However, in 251 BC, Aratus of Sicyon led a rebellion against Antigonus II and in 250 BC, Ptolemy II openly threw his support behind the self-proclaimed king Alexander of Corinth.[182] Although Alexander died in 246 BC and Antigonus was able to score a naval victory against the Ptolemies at the Battle of Andros, the Macedonians lost the Acrocorinth to the forces of Aratus in 243 BC, followed by the induction of Corinth into the Achaean League.[183] Antigonus II finally made peace with the Achaean League in a treaty of 240 BC, ceding the territories that he had lost in Greece.[184] Antigonus II died in 239 BC and was succeeded by his son Demetrius II of Macedon (r. 239 – 229 BC). Seeking an alliance with Macedonia to defend against the Aetolians, the queen mother and regent Olympias II of Epirus offered her daughter Phthia of Macedon to Demetrius II in marriage, which he accepted yet damaged relations with the Seleucids by divorcing Stratonice of Macedon.[185] Although the Aetolians formed an alliance with the Achaean League as a result, Demetrius II was able to invade Boeotia and capture it from the Aetolians by 236 BC.[181]

Demetrius II's control of Greece diminished by the end of his reign, though, when he lost Megalopolis in 235 BC and most of the Peloponnese except Argos to the Achaean League.[186] He also was denied an ally in Epirus when the monarchy was toppled in a republican revolution.[187] Demetrius II's struggle to defend Acarnania against Aetolia became so desperate that he enlisted the aid of the Illyrian king Agron, whose Illyrian pirates raided the coasts of western Greece and even defeated the combined navies of the Aetolian and Achaean Leagues at the Battle of Paxos in 229 BC.[187] Yet another Illyrian ruler Longarus of the Dardanian Kingdom invaded Macedonia and defeated an army of Demetrius II shortly before his death in 229 BC.[188] Although his child son, Philip immediately inherited the throne, his regent Antigonus III Doson (r. 229 – 221 BC), nephew of Antigonus II, was proclaimed king by the army and Philip as his heir following a string of military victories against the Illyrians in the north and the Aetolians in Thessaly.[189]

Although the Achaean League had been fighting Macedonia for decades, Aratus sent an embassy to Antigonus III in 226 BC seeking an unexpected alliance now that the reformist king Cleomenes III of Sparta was threatening the rest of Greece in the Cleomenean War (229–222 BC).[190] In exchange for military aid, Antigonus III demanded the return of Corinth to Macedonian control, which Aratus finally agreed to in 225 BC.[191] Antigonus III's first move against Sparta was to capture Arcadia in the spring of 224 BC.[192] After reforming a Hellenic league in the same vein as Philip II's League of Corinth and hiring Illyrian mercenaries for additional support, Antigonus III managed to defeat Sparta at the Battle of Sellasia in 222 BC.[193] For the first time in Sparta's history, their city was then occupied by a foreign power, restoring Macedonia's position as the leading power in Greece.[194] Antigonus died a year later, perhaps from tuberculosis, leaving behind a strong Hellenistic kingdom for his successor Philip V.[195]

Philip V of Macedon (r. 221 – 179 BC) was only 17 when he acceded to the throne and, despite the successes of his predecessor Antigonus III, faced immediate challenges to his authority by the Illyrian Dardani and Aetolian League.[196] Philip V and his allies were successful against the Aetolians and their allies in the Social War (220–217 BC), yet Philip V pursued a peace settlement with the Aetolians once he heard of a renewed presence of the Dardani in the north and the Carthaginian victory over the Romans at the Battle of Lake Trasimene in 217 BC.[197] Demetrius of Pharos is alleged to have convinced Philip V to first secure Illyria in advance of an invasion of the Italian peninsula.[198] In 216 BC, Philip V sent a hundred light warships into the Adriatic Sea to attack Illyria, a motion that did not go unnoticed by Rome when Scerdilaidas of the Ardiaean Kingdom appealed to the Romans for aid.[199] Rome responded by sending ten heavy quinqueremes from Roman Sicily to patrol the Illyrian coasts, causing Philip V to reverse course and order his fleet to retreat, averting open conflict for the time being.[200]

Conflict with Rome

In 215 BC, at the height of the Second Punic War with the Carthaginian Empire, Roman authorities intercepted a ship off the Calabrian coast holding both a Macedonian envoy and a Carthaginian ambassador to Macedonia, who possessed a Punic document (later translated into Greek and preserved by Polybius) of Hannibal Barca declaring an alliance with Philip V of Macedon.[201] The treaty stipulated that Carthage had the sole right to negotiate terms with Rome after its hypothetical surrender, yet it deferred to the Macedonian interests in the Adriatic Sea and promised mutual aid in the event that a resurgent Rome, after losing its allies in northern and southern Italy, should lash out at either Macedonia or Carthage in revenge.[202] Although the Macedonians were perhaps only interested in safeguarding their conquered territories in Illyria,[203] the Romans were nevertheless able to thwart Philip V's ambitions in the Adriatic during the First Macedonian War (214–205 BC). In 214 BC, Rome positioned a naval fleet at Oricus when it along with Apollonia were assaulted by Macedonian forces.[204] When the Macedonians captured Lissus in 212 BC and potentially threatened southern Italy in support of Hannibal, the Roman Senate responded by inciting the Aetolian League, as well as Attalus I (r. 241 – 197 BC) of Pergamon, Sparta, Elis, and Messenia to wage war against Philip V, keeping him occupied and away from the Italian peninsula.[205]

A year after the Aetolian League concluded a peace agreement with Philip V in 206 BC, the Roman Republic negotiated the Treaty of Phoenice, which ended the war and allowed the Macedonians to retain the settlements they had captured in Illyria.[206] Although the Romans rejected an Aetolian request in 202 BC for Rome to declare war on Macedonia once again, the Roman Senate gave serious consideration to the similar offer made by Pergamon and its ally Rhodes in 201 BC.[207] These states grew increasingly concerned once Philip V formed an alliance with Antiochus III the Great of the Seleucid Empire, which invaded the war-weary and financially exhausted Ptolemaic Empire in the Fifth Syrian War (202–195 BC), while Philip V captured Ptolemaic settlements in the Aegean Sea.[208] Although Rome's envoys played a critical role in convincing Athens to join the anti-Macedonian alliance with Pergamon and Rhodes in 200 BC, the comitia centuriata (i.e. people's assembly) rejected the Roman Senate's proposal for a declaration of war on Macedonia.[209] Meanwhile, Philip V conquered vital territories in the Hellespont and Bosporus as well as Ptolemaic Samos, which led Rhodes to form an alliance with Pergamon, Byzantium, Cyzicus, and Chios against Macedonia.[210] Despite Philip V's nominal alliance with the Seleucid king, he lost the naval Battle of Chios in 201 BC and was subsequently blockaded at Bargylia by a combined fleet of the victorious Rhodian and Pergamene navies.[211]

While Philip V was ensnared in a conflict with several Greek maritime powers, Rome viewed these unfolding events as an opportunity to punish a former ally of Hannibal, come to the aid of its Greek allies, and commit to a war that perhaps required a limited amount of resources in order to achieve victory.[212] With Carthage finally subdued following the Second Punic War, Bringmann contends that the Roman strategy changed from protecting southern Italy from Macedonia, to exacting revenge on Philip V for allying with Hannibal.[213] However, Arthur M. Eckstein stresses that the Roman Senate "did not plot long range-strategies" and instead "lurched from crisis to crisis" while allowing itself to become involved in the Hellenistic east only at the strong urging of its allies and despite its own exhausted and war-weary populace.[214] The Roman Senate demanded that Philip V cease hostilities against neighboring Greek powers and defer to an international arbitration committee for any and all grievances. Seeking either war or humiliation for the Macedonian king, his predictable rejection of their proposal served as a useful tool of propaganda demonstrating the honorable and philhellenic intentions of the Romans contrasted with the combative and antagonistic Macedonian response.[215] When the comitia centuriata finally voted in approval of the Roman Senate's declaration of war and handed their ultimatum to Philip V by the summer of 200 BC, demanding that a tribunal assess the damages owed to Rhodes and Pergamon, the Macedonian king rejected it outright. This marked the beginning of the Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC), with Publius Sulpicius Galba Maximus spearheading military operations by landing at Apollonia along the coast of Illyria with two Roman legions.[216]

_da_orig%252C._ellenistico_su_busto_moderno%252C_MANN_02.JPG.webp)

Although the Macedonians were able to successfully defend their territory for roughly two years,[217] the Roman consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus managed to expel Philip V from Macedonia in 198 BC with him and his forces taking refuge in Thessaly.[218] When the Achaean League abandoned Philip V to join the Roman-led coalition, the Macedonian king sued for peace, but the terms offered were considered too stringent and so the war continued.[218] In June 197 BC, the Macedonians were defeated at the Battle of Cynoscephalae.[219] Rome, dismissing the Aetolian League's demands to dismantle the Macedonian monarchy altogether, ratified a treaty that forced Macedonia to relinquish control of much of its Greek possessions, including Corinth, while allowing it to preserve its core territory, if only to act as a buffer against Illyrian and Thracian incursions into Greece.[220] Although the Greeks, especially the Aetolians, suspected Roman intentions of supplanting Macedonia as the new hegemonic power in Greece, Flaminius announced at the Isthmian Games of 196 BC that Rome intended to preserve Greek liberty by leaving behind no garrisons or exacting tribute of any kind.[221] This promise was delayed due to the Spartan king Nabis capturing Argos, necessitating Roman intervention and a peace settlement with the Spartans, yet the Romans finally evacuated Greece in the spring of 194 BC.[222]

Encouraged by the Aetolian League and their calls to liberate Greece from the Romans, the Seleucid king Antiochus III landed with his army at Demetrias, Thessaly in 192 BC, and was elected strategos by the Aetolians.[223] However, Philip V of Macedon maintained his alliance with the Romans, along with the Achaean League, Rhodes, Pergamon, and Athens.[224] The Romans defeated the Seleucids in the 191 BC Battle of Thermopylae as well as the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BC, forcing the Seleucids to pay a war indemnity, dismantle most of its navy, and abandon its claims to any territories north or west of the Taurus Mountains in the Treaty of Apamea in 188 BC.[225] In 191–189 BC, Philip V, with Rome's acceptance, was able to capture some cities in central Greece that had been allied to Antiochus III, while Rhodes and Eumenes II (r. 197 – 159 BC) of Pergamon gained significantly larger territories in Asia Minor.[226]

While becoming increasingly entangled in Greek affairs and failing to please all sides in various disputes, the Roman Senate decided in 184/183 BC to force Philip V to abandon the cities of Aenus and Maronea, since these were declared free cities in the Treaty of Apamea.[227] It also assuaged the fears of Eumenes II that these Macedonian-held settlements would no longer threaten the security of his possessions in the Hellespont.[228] Perseus of Macedon (r. 179 – 168 BC) succeeded Philip V and executed his brother Demetrius, who had been favored by the Romans yet was charged by Perseus with high treason.[229] Perseus then attempted to form marriage alliances with Prusias II of Bithynia and Seleucus IV Philopator of the Seleucid Empire, along with renewed relations with Rhodes that greatly unsettled Eumenes II.[230] Although Eumenes II attempted to undermine these diplomatic relationships, Perseus fostered an alliance with the Boeotian League, extended his authority into Illyria and Thrace, and in 174 BC, won the role of managing the Temple of Apollo at Delphi in the Amphictyonic Council.[231]

Eumenes II came to Rome in 172 BC and delivered a speech to the Senate denouncing the alleged crimes and transgressions of Perseus.[232] This convinced the Roman Senate to declare the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC), although Klaus Bringmann asserts that negotiations with Macedonia were completely ignored due to Rome's "political calculation" that the Macedonian kingdom had to be destroyed in order to ensure the elimination of the "supposed source of all the difficulties which Rome was having in the Greek world".[233] Although Perseus' forces were victorious against the Romans at the Battle of Callinicus in 171 BC, the Macedonian army was defeated at the Battle of Pydna in June 168 BC.[234] Perseus fled to Samothrace but surrendered shortly afterwards, was brought to Rome for the triumph of Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, and placed under house arrest at Alba Fucens where he died in 166 BC.[235]

The Romans formally disestablished the Macedonian monarchy by installing four separate allied republics in its stead, their capitals located at Amphipolis, Thessalonica, Pella, and Pelagonia.[236] The Romans imposed severe laws inhibiting many social and economic interactions between the inhabitants of these respective republics, including the banning of marriages between them and the (temporary) prohibition on the use of Macedonia's gold and silver mines.[236] However, a certain Andriscus claiming Antigonid descent rebelled against the Romans and was pronounced king of Macedonia, defeating the army of the Roman praetor Publius Iuventius Thalna during the Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BC).[237] Despite this, Andriscus was defeated in 148 BC at the second Battle of Pydna by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus, whose forces occupied the kingdom.[238] This was followed in 146 BC by the Roman destruction of Carthage and victory over the Achaean League at the Battle of Corinth, ushering in the era of Roman Greece and the gradual establishment of the Roman province of Macedonia.[239]

See also

References

- Gabriel, Richard A. (2010). Philip II of Macedonia: Greater Than Alexander. Potomac Books. p. 232. ISBN 1597975192.

That sense of being one people allowed each Greek state and its citizens to contribute their values, experiences, traditions, resources, and talents to a new national identity and psyche. It was not until Philip's reign that a common sentiment of what it meant to be a Hellene reached all Greeks. Alexander took this culture of Hellenism with him to Asia, but it was Philip, as leader of the Greeks, who created it and in doing so made the Hellenistic Age possible.

- Kinzl, Konrad H (2010). A Companion to the Classical Greek World. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 553. ISBN 1444334123.

He [Philip] also recognized the power of pan-hellenic sentiment when arranging Greek affairs after his victory at Chaironeia: a pan-hellenic expedition against Persia ostensibly was one of the main goals of the League of Corinth.

- Burger, Michael (2008). The Shaping of Western Civilization: From Antiquity to the Enlightenment. University of Toronto Press. p. 76. ISBN 1551114321.

In the end, the Greeks would fall under the rule of a single man, who would unify Greece: Philip II, king of Macedon (360-336 BC). His son, Alexander the Great, would lead the Greeks on a conquest of the ancient Near East vastly expanding the Greek world.

- King 2010, p. 376; Sprawski 2010, p. 127; Errington 1990, pp. 2–3.

- Titus Livius, "The History of Rome", 45.9: "This was the end of the war between the Romans and Perseus, after four years of steady campaigning, and also the end of a kingdom famed over a large part of Europe and all of Asia. They reckoned Perseus as the twentieth after Caranus, who founded the kingdom."

- Marcus Velleius Paterculus, "History of Rome", 1.6: "In this period, sixty-five years before the founding of Rome, Carthage was established by the Tyrian Elissa, by some authors called Dido. About this time also Caranus, a man of royal race, eleventh in descent from Hercules, set out from Argos and seized the kingship of Macedonia. From him Alexander the Great was descended in the seventeenth generation, and could boast that, on his mother's side, he was descended from Achilles, and, on his father's side, from Hercules.”

- Justin, "Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus", 7.1.7: "But Caranus accompanied by a great multitude of Greeks, having been directed by an oracle to seek a settlement in Macedonia, and having come into Emathia, and followed a flock of goats that were fleeing from a tempest, possessed himself of the city of Edessa...”

- Plutarch, “Alexander”, 2.1: "As for the lineage of Alexander, on his father's side he was a descendant of Heracles through Caranus, and on his mother's side a descendant of Aeacus through Neoptolemus; this is accepted without any question."

- Pausanias, "Description of Greece", 9.40.8–9: "The Macedonians say that Caranus, king of Macedonia, overcame in battle Cisseus, a chieftain in a bordering country. For his victory Caranus set up a trophy after the Argive fashion, but it is said to have been upset by a lion from Olympus, which then vanished. Caranus, they assert, realized that it was a mistaken policy to incur the undying hatred of the non-Greeks dwelling around, and so, they say, the rule was adopted that no king of Macedonia, neither Caranus himself nor any of his successors, should set up trophies, if they were ever to gain the good-will of their neighbors. This story is confirmed by the fact that Alexander set up no trophies, neither for his victory over Dareius nor for those he won in India."

- Errington 1990, p. 3.

- King 2010, p. 376; Sprawski 2010, p. 127.

- Badian 1982, p. 34; Sprawski 2010, p. 142.

- King 2010, p. 376; Errington 1990, p. 251.

- King 2010, p. 376.

- Errington 1990, p. 2.

- Lewis & Boardman 1994, pp. 723–724, see also Hatzopoulos 1996, pp. 105–108 for the Macedonian expulsion of original inhabitants such as the Phrygians.

- Anson 2010, p. 5.

- Anson 2010, pp. 5–6.

- Thomas 2010, pp. 67–68, 74–78.

- Olbrycht 2010, p. 343; Sprawski 2010, p. 134; Errington 1990, p. 8.

- Olbrycht 2010, pp. 342–343; Sprawski 2010, pp. 131, 134; Errington 1990, pp. 8–9;

Errington seems far less convinced that at this point Amyntas I of Macedon offered any submission as a vassal at all, at most a token one. He also mentions how the Macedonian king pursued his own course of action, such as inviting the exiled Athenian tyrant Hippias to take refuge at Anthemous in 506 BC. - Olbrycht 2010, p. 343.

- Olbrycht 2010, p. 343; Sprawski 2010, p. 136; Errington 1990, p. 10.

- Olbrycht 2010, p. 344; Sprawski 2010, pp. 135–137; Errington 1990, pp. 9–10.

- Sprawski 2010, p. 137.

- Olbrycht 2010, p. 344; Errington 1990, p. 10.

- Olbrycht 2010, pp. 344–345; Sprawski 2010, pp. 138–139.

- Sprawski 2010, pp. 139–140.

- Olbrycht 2010, p. 345; Sprawski 2010, pp. 139–141; see also Errington 1990, pp. 11–12 for further details.

- Sprawski 2010, pp. 141–142; Errington 1990, pp. 9, 11–12.

- Sprawski 2010, p. 143.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 145–146.

- Roisman 2010, p. 146; see also Errington 1990, pp. 13–14 for further details.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 146–147; Müller 2010, p. 171; Cawkwell 1978, p. 72; see also Errington 1990, pp. 13–14, 16 for further details.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 146–147.

- Roisman 2010, p. 147; see also Errington 1990, p. 18 for further details.

- Roisman 2010, p. 147.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 147–148.

- Roisman 2010, p. 148.

- Roisman 2010, p. 148; Errington 1990, pp. 19–20.

- Roisman 2010, p. 149.

- Roisman 2010, p. 149; Errington 1990, p. 20.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 149–150; Errington 1990, p. 20.

- Roisman 2010, p. 150; Errington 1990, p. 20.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 150–151; Errington 1990, pp. 21–22.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 151–152; Errington 1990, pp. 21–22.

- Roisman 2010, p. 152; Errington 1990, p. 22.

- Roisman 2010, p. 152; Errington 1990, pp. 22–23.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 152–153.

- Roisman 2010, p. 153; Errington 1990, pp. 22–23.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 153–154; see also Errington 1990, p. 23 for further details.

- Roisman 2010, p. 154; see also Errington 1990, p. 23 for further details.

- Roisman 2010, p. 154; Errington 1990, pp. 23–24.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 154–155; Errington 1990, p. 24.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 155–156.

- Roisman 2010, p. 156; Errington 1990, p. 26.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 156–157.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 156–157; Errington 1990, p. 26.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 157–158; Errington 1990, p. 28.

- Roisman 2010, p. 158; Errington 1990, pp. 28–29.

- Roisman 2010, p. 158.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 158–159; see also Errington 1990, p. 30 for further details.

- Roisman 2010, p. 159; see also Errington 1990, p. 30 for further details.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 159–160;

- Roisman 2010, p. 160; Errington 1990, pp. 32–33.

- Roisman 2010, p. 161; Errington 1990, pp. 34–35.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 161–162; Errington 1990, p. 35.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 161–162; Errington 1990, pp. 35–36.

- Roisman 2010, p. 162; Errington 1990, pp. 35–36.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 162–163; Errington 1990, p. 36.

- Roisman 2010, pp. 163–164; Errington 1990, p. 37.

- Müller 2010, pp. 166–167; Buckley 1996, pp. 467–472.

- Müller 2010, pp. 167–168; Buckley 1996, pp. 467–472.

- Müller 2010, pp. 167–168; Buckley 1996, pp. 467–472; Errington 1990, pp. 38.

- Müller 2010, p. 167.

- Müller 2010, p. 168.

- Müller 2010, pp. 168–169.

- Müller 2010, pp. 169–170, 179;

Müller is skeptical about the claims of Plutarch and Athenaeus that Philip II of Macedon married Cleopatra Eurydice of Macedon, a younger woman, purely out of love or due to his own midlife crisis. Cleopatra was the daughter of the general Attalus, who along with his father-in-law Parmenion were given command posts in Asia Minor (modern Turkey) soon after this wedding. Müller also suspects that this marriage was one of political convenience meant to ensure the loyalty of an influential Macedonian noble house. - Müller 2010, p. 169.

- Müller 2010, p. 170; Buckler 1989, p. 62.

- Müller 2010, pp. 170–171; Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 187.

- Müller 2010, pp. 167, 169; Roisman 2010, p. 161.

- Müller 2010, pp. 169, 173–174; Cawkwell 1978, p. 84; Errington 1990, pp. 38–39.

- Müller 2010, p. 171; Buckley 1996, pp. 470–472; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 74–75.

- Müller 2010, p. 172; Hornblower 2002, p. 272; Cawkwell 1978, p. 42; Buckley 1996, pp. 470–472.

- Müller 2010, pp. 171–172; Buckler 1989, pp. 63, 176–181; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 185–187;

Cawkwell contrarily provides the date of this siege as 354–353 BC. - Müller 2010, pp. 171–172; Buckler 1989, pp. 8, 20–22, 26–29.

- Müller 2010, pp. 172–173; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 60, 185; Hornblower 2002, p. 272; Buckler 1989, pp. 63–64, 176–181;

Conversely, Buckler provides the date of this initial campaign as 354 BC, while affirming that the second Thessalian campaign ending in the Battle of Crocus Field occurred in 353 BC. - Müller 2010, p. 173; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 62, 66–68; Buckler 1989, pp. 74–75, 78–80; Worthington 2008, pp. 61–63.

- Müller 2010, p. 173; Cawkwell 1978, p. 44; Schwahn 1931, col. 1193–1194.

- Cawkwell 1978, p. 86.

- Müller 2010, pp. 173–174; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 85–86; Buckley 1996, pp. 474–475.

- Müller 2010, pp. 173–174; Worthington 2008, pp. 75–78; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 96–98.

- Müller 2010, p. 174; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 98–101.

- Müller 2010, pp. 174–175; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 95, 104, 107–108; Hornblower 2002, pp. 275–277; Buckley 1996, pp. 478–479.

- Müller 2010, p. 175.

- Müller 2010, pp. 175–176; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 114–117; Hornblower 2002, p. 277; Buckley 1996, p. 482; Errington 1990, p. 44.

- Mollov & Georgiev 2015, p. 76.

- Müller 2010, p. 176; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 136–142; Errington 1990, pp. 82–83.

- Müller 2010, pp. 176–177; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 143–148.

- Harris, Edward (2001). Dinarchus, Hyperides and Lycurgus. Austin, Texas: University of Texas. pp. 80–83. ISBN 0-292-79142-9.

- Müller 2010, p. 177; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 167–168.

- Müller 2010, pp. 177–178; Cawkwell 1978, pp. 167–171; see also Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 16 for further details.

- Olbrycht 2010, pp. 348, 351

- Olbrycht 2010, pp. 347–349

- Olbrycht 2010, p. 351

- Errington 1990, p. 227.

- Müller 2010, pp. 179–180; Cawkwell 1978, p. 170.

- Müller 2010, pp. 180–181; see also Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 14 for further details.

- Müller 2010, pp. 181–182; Errington 1990, p. 44; Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 186; see Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 3–5 for details of the arrests and judicial trials of other suspects in the conspiracy to assassinate Philip II of Macedon.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 189–190; Müller 2010, p. 183.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 190; Müller 2010, pp. 182–183;

Without implicating Alexander III of Macedon as a potential suspect in the plot to assassinate Philip II of Macedon, N.G.L. Hammond and F.W. Walbank discuss possible Macedonian as well as foreign suspects, such as Demosthenes and Darius III: Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 8–12. - Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 190; Müller 2010, p. 183; Renault 2001, pp. 61–62; Fox 1980, p. 72; see also Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 3–5 for further details.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 186.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 190.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 190–191; see also Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 15–16 for further details.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 191.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 191; Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 34–38.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 191; Hammond & Walbank 2001, pp. 40–47.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 191; see also Errington 1990, p. 91 and Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 47 for further details.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 191–192; see also Errington 1990, pp. 91–92 for further details.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 192–193.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 193.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 193–194; Holt 2012, pp. 27–41.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 193–194.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 194; Errington 1990, p. 113.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 195.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 194–195.

- Errington 1990, pp. 105–106.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 198.

- Holt 1989, pp. 67–68.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 196.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 199; Errington 1990, p. 93.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 199–200; Errington 1990, pp. 44, 93;

Gilley and Worthington discuss the ambiguity about the exact title of Antipater aside from deputy hegemon of the League of Corinth, with some sources calling him a regent, others a governor, others a simple general.

N.G.L. Hammond and F.W. Walbank state that Alexander the Great left "Macedonia under the command of Antipater, in case there was a rising in Greece." Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 32. - Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 200–201; Errington 1990, p. 58.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 201.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 201–203.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 204; see also Errington 1990, p. 44 for further details.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 204; see also Errington 1990, pp. 115–117 for further details.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 204; Adams 2010, p. 209; Errington 1990, pp. 69–70, 119.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, pp. 204–205; Adams 2010, pp. 209–210; Errington 1990, pp. 69, 119.

- Gilley & Worthington 2010, p. 205; see also Errington 1990, p. 118 for further details.

- Adams 2010, pp. 208–209; Errington 1990, p. 117.

- Adams 2010, pp. 210–211; Errington 1990, pp. 119–120.

- Adams 2010, p. 211; Errington 1990, pp. 120–121.

- Adams 2010, pp. 211–212; Errington 1990, pp. 121–122.

- Adams 2010, pp. 207 n. #1, 212; Errington 1990, pp. 122–123.