History of immigration to Canada

The history of immigration to Canada details the movement of people to modern-day Canada, which also belongs to a wider debate continuing among anthropologists over various possible models of Settlement of the American to the New World, as well as their pre-contact populations.

| Part of a series on |

| Canadian citizenship and immigration |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

The Inuit are believed to have arrived entirely separately from other indigenous peoples, around 1200 CE. Indigenous peoples contributed significantly to the culture and economy of the early European colonies, and as such have played an important role in fostering a unique Canadian cultural identity.

Statistics Canada has tabulated the effect of immigration on population growth in Canada from 1851 to 2001.[1] On average, censuses are taken every 10 years, which is how Canadian censuses were first incremented between 1871 and 1901. Beginning in 1901, the Dominion Government changed its policy so that census-taking occurred every 5 years subsequently. This was to document the effects of the advertising campaign initiated by Clifford Sifton.

In 2018, Canada received 321,035 immigrants. The top ten countries of origin, which provided 61% of these, were India (69, 973), Philippines (35,046), China (29,709),, Syria (12, 046), United States (10, 907), Pakistan (9,488), France (6,175), Eritrea (5,689), and United Kingdom and Overseas territories (5,663). [2]

History of Canadian nationality law

In 1828, during the Great Migration of Canada, Britain passed the Act to Regulate the Carrying of Passengers in Merchant Vessels, the country's first legislative recognition of its responsibility over the safety and well-being of immigrants leaving the British Isles. The Act limited the number of passengers who could be carried on a ship regulated the amount of space allocated to them; and required that passengers be supplied with adequate sustenance on the voyage. The 1828 Act is now recognized as the foundation of British colonial emigration legislation.[3]

Canadian citizenship was originally created under the Immigration Act, 1910, to designate those British subjects who were domiciled in Canada, while all other British subjects required permission to land. A separate status of 'Canadian national' was created under the Canadian Nationals Act, 1921, which defined such British subjects as being Canadian citizens, as well as their wives and children (fathered by such citizens) who had not yet landed in Canada. Following the passage of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, the monarchy thus ceased to be an exclusively British institution. As result, Canadians—just as all others living among the Commonwealth realms—were known as subjects of the Crown, while the term "British subject" would continue to be used in legal documents.

Canada was the second nation among what was then the British Commonwealth to establish its own nationality law in 1946, with the enactment of the Canadian Citizenship Act, 1946, taking effect on 1 January 1947. To acquire Canadian citizenship from then forward, one would generally have to either be a British subject on or before the Act took effect; an 'Indian' or 'Eskimo'; or had to have been admitted to Canada as landed immigrants before the Act took effect. A British subject at that time was anyone from the UK or its colonies (Commonwealth countries). Acquisition and loss of British subject status before 1947 was determined by United Kingdom law (see History of British nationality law).

On February 15, 1977, Canada removed restrictions on dual citizenship. Many of the provisions to acquire or lose Canadian citizenship that existed under the 1946 legislation were repealed. Canadian citizens are in general no longer subject to involuntary loss of citizenship, barring revocation on the grounds of immigration fraud or criminality. The term "Canadians of convenience" was popularized by Canadian politician Garth Turner in 2006 in conjunction with the evacuation of Canadian citizens from Lebanon during the 2006 Israel–Lebanon conflict. It refers to people with multiple citizenship who immigrated to Canada, met the residency requirement to obtain citizenship, obtained Canadian citizenship, and moved back to their original home country while maintaining their Canadian citizenship, with those who support the term claiming they do so as a safety net.

Regional history

Atlantic Region

There are a number of reports of contact made before Columbus between the first peoples and those from other continents. The case of Viking contact is supported by the remains of a Viking settlement in L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, although there is no direct proof this was the place Icelandic Norseman Leifur Eiríksson referred to as Vinland around the year 1000.

The presence of Basque cod fishermen and whalers, just a few years after Columbus, has also been cited, with at least nine fishing outposts having been established on Labrador and Newfoundland. The largest of these settlements was the Red Bay station, with an estimated 900 people. Basque whalers may have begun fishing the Grand Banks as early as the 15th century.

The next European explorer acknowledged as landing in what is now Canada was John Cabot, who landed somewhere on the coast of North America (probably Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island) in 1497 and claimed it for King Henry VII of England. Portuguese and Spanish explorers also visited Canada, but it was the French who first began to explore further inland and set up colonies, beginning with Jacques Cartier in 1534. Under Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons, the first French settlement was made in 1604 in the region of New France known as Acadie on Isle Sainte-Croix (which now belongs to Maine) in the Bay of Fundy. That winter was particularly long and harsh and about half of the settlers that had accompanied Sieur de Mons died of scurvy. The following year they decided to move to a better sheltered area, establishing a new settlement at Port-Royal. In 1608, Samuel de Champlain, established a settlement at Donnacona; it would later grow to become Quebec City. The French claimed Canada as their own and 6,000 settlers arrived, settling along the St. Lawrence and in the Maritimes. Britain also had a presence in Newfoundland and, with the advent of settlements, claimed the south of Nova Scotia as well as the areas around the Hudson Bay.

The first contact with the Europeans was disastrous for the first peoples. Explorers and traders brought European diseases, such as smallpox, which killed off entire villages. Relations varied between the settlers and the Natives. The French befriended the Huron peoples and entered into a mutually beneficial trading relationship with them. The Iroquois, however, became dedicated opponents of the French and warfare between the two was unrelenting, especially as the British armed the Iroquois in an effort to weaken the French.

Quebec

After Samuel de Champlain's founding of Quebec City in 1608, it became the capital of New France. While the coastal communities were based upon the cod fishery, the economy of the interior revolved around beaver fur, which was popular in Europe. French voyageurs would travel into the hinterlands and trade with the natives. The voyageurs ranged throughout what is today Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba trading guns, gunpowder, textiles and other European manufacturing goods with the natives for furs. The fur trade encouraged only a small population, however, as minimal labour was required. Encouraging settlement was always difficult, and while some immigration did occur, by 1760 New France had a population of only some 70,000.

New France had other problems besides low immigration. The French government had little interest or ability in supporting its colony and it was mostly left to its own devices. The economy was primitive and much of the population was involved in little more than subsistence agriculture. The colonists also engaged in a long-running series of wars with the Iroquois.

Ontario

Étienne Brûlé explored Ontario from 1610 to 1612. In 1615, Samuel de Champlain visited Lake Huron, after which French missionaries established outposts in the region.

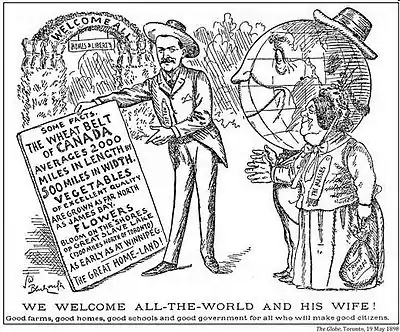

Prairie provinces

In the 18th to 19th century, the only immigration western Canada or Rupert's Land saw was early French Canadian North West Company fur traders from eastern Canada, and the Scots, English Adventurers and Explorers representing the Hudson's Bay Company who arrived via Hudson Bay. Canada became a nation in 1867, Rupert's Land became absorbed into the North-West Territories. To encourage British Columbia to join the confederation, a transcontinental railway was proposed. The railway companies felt it was not feasible to lay track over land where there was no settlement. The fur trading era was declining; as the buffalo population disappeared, so too did the nomadic buffalo hunters, which presented a possibility to increase agricultural settlement. Agricultural possibilities were first expounded by Henry Youle Hind. The Dominion government with the guidance of Clifford Sifton, Minister of the Interior in charge of immigration, (1896–1905)[4] enacted Canada's homesteading act, the Dominion Lands Act, in 1872. An extensive advertising campaign throughout western Europe and Scandinavia brought in a huge wave of immigrants to "The Last, Best West". (In 1763 Catherine the Great issues Manifesto inviting foreigners to settle in Russia,[5] and in 1862 the United States enacted a Homestead Act inviting immigration to America.)[6]

Ethnic or religious groups seeking asylum or independence no longer traveled to Russia or the United States where lands were taken or homestead acts were canceled. The Red River Colony population of Manitoba allowed it to become a province in 1870. In the 1880s less than 1000 non-Aboriginal people resided out west. The government's immigration policy was a huge success, the North-West Territories grew to a population of 56,446 in 1881 and almost doubled to 98,967 in 1891, and exponentially jumped to 211,649 by 1901.[7] Ethnic Bloc Settlements[8] dotted the prairies, as language groupings settled together on soil types of the Canadian western prairie similar to agricultural land of their homeland. In this way immigration was successful; new settlements could grow because of common communication and learned agricultural methods. Canada's CPR transcontinental railway was finished in 1885. Immigration briefly ceased to the West during the North West Rebellion of 1885. Various investors and companies were involved in the sale of railway (and some non railway) lands. Sifton himself may have been involved as an investor in some of these ventures.[9] Populations of Saskatchewan and Alberta were eligible for provincial status in 1905. Immigration continued to increase through to the roaring twenties. A mass exodus affected the prairies during the dirty thirties depression years and the prairies have never again regained the impetus of the immigration wave seen in the early 20th century.

British Columbia

Until the railway, immigration to British Columbia was either via sea, or – once the gold rushes were under way – via overland travel from California and other parts of the US, as there was no usable route westward beyond the Rockies, and travel on the Prairies and across the Canadian Shield was still water-borne. BC's very small early non-native population was dominantly French-Canadian and Metis fur-company employees, their British (largely Scottish) administrators and bosses, and a population of Kanakas (Hawaiians) in the company's employ, as well as members of various Iroquoian peoples, also in the service of the fur company. The non-local native population of the British Pacific was in the 150–300 range until the advent of the Fraser Gold Rush in 1857, when Victoria's population swelled to 30,000 in four weeks and towns of 10,000 and more appeared at hitherto-remote locations on the Mainland, at Yale, Port Douglas, and Lillooet (then called Cayoosh Flat). This wave of settlement was near-entirely from California, and was approximately one-third each American, Chinese and various Europeans and others; nearly all had been in California for many years, including the early Canadians and Maritimers who made the journey north to the new Gold Colony, as British Columbia was often called.

One group of about 60, called the Overlanders of '62, did make the journey from Canada via Rupert's Land during the Cariboo Gold Rush, though they were the exception to the rule. An earlier attempt to move some of the settlers of the Selkirk Colony ended in disaster at Dalles des Morts, near present-day Revelstoke. Early immigration to British Columbia was from all nations, largely via California, and included Germans, Scandinavians, Maritimers, Australians, Poles, Italians, French, Belgians and others, as well as Chinese and Americans who were the largest groups to arrive in the years around the time of the founding of the Mainland Colony in 1858. Most of the early Americans left in the early 1860s because of the US Civil War as well as in pursuit of other gold rushes in Idaho, Colorado and Nevada, though Americans remained a major component in the settler population ever since. During the 1860s, in conjunction with the Cariboo Gold Rush and agitation to join Canada, more and more Canadians (including the Overlanders, who became influential) arrived and became a force in the local polity, which hitherto had been dominated by Britons favouring separate rule, and helped contribute towards the agenda for annexation with Canada. After the opening of the CPR, a new wave of immigration led not just to the creation of Vancouver and other newer urban settlements, but also to the settlement of numerous regions in the Interior, especially the Okanagan, Boundary, Shuswap, and Kootenays. A similar wave of settlement and development accompanied the opening of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (today the CNR) through the Central Interior, which was also the impetus for the creation of the city of Prince George and the port of Prince Rupert.

Head tax and Chinese Immigration Act of 1923

The first immigrants from China to Canada came from California to the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush in British Columbia, beginning in 1858; immigrants directly from China did not arrive until 1859. The Chinese were a significant part of nearly all the British Columbia gold rushes and most towns in BC had large Chinese populations, often a third of the total or more. Chinese labourers were hired to help with the construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road and Alexandra Bridge as well as the Douglas Road and other routes. Chinese miners, merchants and ranchers enjoyed full rights to mineral tenure and land alienation and in some areas became the mainstay of the local economy for decades. Chinese, for instance, owned 60% of the land in the Lillooet Land District in the 1870s and 1880s and held the majority of working claims on the Fraser River and in other areas. The next wave of immigrants from China were labourers brought in to help build the C.P.R. transcontinental railway but many defected to the goldfields of the Cariboo and other mining districts. In the year the railway was completed the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 was enacted, and a head tax was levied to control the ongoing influx of labour, although immigration continued as corporate interests in BC preferred to hire the cheaper labour made available to them by Chinese labour contractors; Chinese labour was brought in by the Dunsmuir coal interests used to break the back of strikers at Cumberland in the Comox Valley, which then became one of BC's largest Chinatowns as white workers formerly resident there had been displaced by armed force.

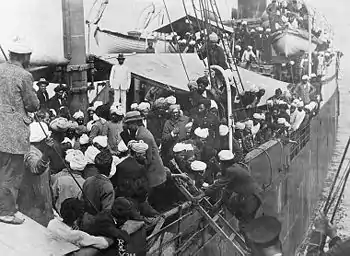

Indian immigration and Continuous Journey Regulation of 1908

The Canadian government's first attempt to restrict immigration from India was to pass an order-in-council on January 8, 1908, that prohibited immigration of persons who "in the opinion of the Minister of the Interior" did not "come from the country of their birth or citizenship by a continuous journey and or through tickets purchased before leaving their country of their birth or nationality." In practice this applied only to ships that began their voyage in India, as the great distance usually necessitated a stopover in Japan or Hawaii. These regulations came at a time when Canada was accepting massive numbers of immigrants (over 400,000 in 1913 alone – a figure that remains unsurpassed to this day), almost all of whom came from Europe. Though Gurdit Singh, was apparently aware of regulations when he chartered the Komagata Maru in January 1914,[10] he continued with his purported goal of challenging these exclusion laws in order to have a better life. The Komagata Maru, a Japanese steamship that sailed from Hong Kong to Shanghai, China; Yokohama, Japan; and then to Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, in 1914, carried 376 passengers from Punjab, India. The passengers were not allowed to land in Canada and the ship was forced to return to India. The passengers consisted of 340 Sikhs, 24 Muslims, and 12 Hindus, all British subjects. This was one of several incidents in the early 20th century involving exclusion laws in Canada and the United States designed to keep out immigrants of Asian origin. Times have now changed, and India has become the largest source of immigrants for Canada. In 2019, India topped the list of immigrants admitted to Canada. Canada welcomed 85,590 Indian nationals, followed by 30,245 from China and 27,820 from the Philippines.[11]

Early European settlements

Scandinavian colonists and settlement

Scandinavians were a strong contingent of the original arrivals from California and distinguished themselves in the establishment of the early timber industry and especially in the foundations of the commercial fishery. Semi-utopian and religious Scandinavian colonies arrived at certain places – Cape Scott and Holberg, British Columbia and nearby areas for the Danes, Sointula and Websters Corners for the Finns, and Bella Coola and locations nearby, such as Tallheo. All originally socialist or Christian attempts at new societies, these wound up breaking up though the populations such as the Norwegians at Bella Coola continued on in the fishery, building and running canneries (of which Tallheo was one).

German colonists and settlement

German colonists, like the Scandinavians, were among the earliest to arrive from California and established themselves beyond mining in areas such as ranching and construction and specialized trades. Until World War I, Vancouver was a major centre of German investment and social life and German was commonly heard on the city's streets and bars. They remained the largest non-British group in the province until eclipsed in that capacity by the Chinese in the 1980s.

Doukhobor settlement and communities

The Doukhobor people were assisted in their immigration by Count Leo Tolstoy who admired them for their collectarian lifestyle and beliefs and ardent pacifism and freedom from materialism. Originally settled in Saskatchewan, and restive of the government's desire to send their children to public school and other matters, they migrated en masse to British Columbia to settle in the West Kootenay and Boundary regions.

Waves of migration

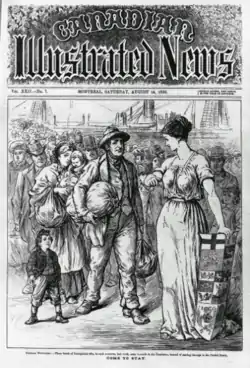

The Great Migration

The Great Migration of Canada (also known as the Great Migration from Britain) was a period of high immigration to Canada from 1815 to 1850, involving over 800,000 immigrants chiefly from the British Isles. Unlike the later 19th century/early 20th century when organized immigration schemes brought in much of the new immigrants to Canada, this period of immigration was demand driven based on the need for infrastructure labour in the burgeoning colonies, filling new rural settlements and poor conditions in some source places, such the Highland Clearances in Scotland and later, the Great Famine of Ireland.[12] Though Europe was in an overall sense becoming richer through the Industrial Revolution, steep population growth made the relative number of jobs low, and overcrowded conditions forcing many to look to North America for economic success.[13]

Immigration to the West

Attempts to form permanent settlement colonies west of the Great Lakes were beset by difficulty and isolation until the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the second of the two Riel Rebellions. Despite the railway making the region more accessible, there were fear that a tide of settlers from the United States might overrun British territory. In 1896, Minister of the Interior Clifford Sifton launched a program of settlement with offices and advertising in the United Kingdom and continental Europe. This began a major wave of railway-based immigration which created the farms, towns and cities of the Prairie provinces.

Third wave (1890–1920) and fourth wave (1940s–1960s)

The third wave of immigration to Canada coming mostly from continental Europe peaked prior to World War I, between 1911 and 1913 (over 400,000 in 1912), many from Eastern or Southern Europe. The fourth wave came from Europe after the Second World War, peaking at 282,000 in 1957. Many were from Italy and Portugal. Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia was an influential port for European immigration; it received 471,940 Italians between 1928 until it ceased operations in 1971, making Italians the third largest ethnic group to immigrate to Canada during that time period.[14] Together, they made Canada a more multi-ethnic country with substantial non-British or non-French European elements. For example, Ukrainian Canadians accounted for the largest Ukrainian population outside Ukraine and Russia. The Church of England took up the role of introducing British values to farmers newly arrived on the prairies. In practice, they clung to their traditional religious affiliations.[15]

Periods of low immigration have also occurred: international movement was very difficult during the world wars, and there was a lack of jobs "pulling" workers out of Canada during the Great Depression in Canada.

Canadianization was a high priority for new arrivals lacking a British cultural background.[16] Immigrants from Britain were given highest priority.[17] There was no special effort to attract Francophone immigrants. In terms of economic opportunity, Canada was most attractive to farmers headed to the Prairies, who typically came from eastern and central Europe. Immigrants from Britain preferred urban life.[18]

Fifth wave (1970s–present)

Immigration since the 1970s has overwhelmingly been of visible minorities from the developing world. This was largely influenced in 1976 when the Immigration Act was revised and this continued to be official government policy. During the Mulroney government, immigration levels were increased. By the late 1980s, the fifth wave of immigration has maintained with slight fluctuations since (225,000–275,000 annually). Currently, most immigrants come from South Asia, China and the Caribbean and this trend is expected to continue.

History of immigration legislations

The following is the chronology of Canadian immigration and citizenship laws.

- Naturalization Act (May 22, 1868 - December 22 31, 1946). All Canadians born inside and outside Canada, were subject to the crown or "British Subjects".[19]

- Canadian Citizenship Act (January 1, 1947). This act legitimized and acknowledged Canadian citizenship.[19]

- Citizenship Act (February 15, 1977). This act recognized dual citizenship and abolished "special treatment" to the British subjects.[19]

- Bill C-14: An Act to amend the Citizenship Act with clauses for Adopted Children (December 23, 2007). An act which provided that adopted children will automatically acquire Canadian citizenship without going through the application for permanent resident stage.[19]

- Bill C-37: An Act to amend the Citizenship Act (April 17, 2009). An act intended to limit the citizenship privilege to first generation only and gave the opportunity to Canadian citizens to re-acquire their citizenship, hence, repealing provisions from former legislation.[19]

- Bill C-24: Strengthening the Canadian Citizenship Act (Royal Assent: June 19, 2014; Came into force: June 11, 2015). "The Act contains a range of legislative amendments to further improve the citizenship program."[19]

- Bill C-6: An Act to amend the Citizenship Act (Royal Assent: June 19, 2017; Came into force: October 11, 2017). This act will give "stateless" person an opportunity to be granted with Canadian citizenship which "statelessness" is considered as a legal ground for granting such privilege. This is only one of the many changes included in this new amendment of the Citizenship Act.[20]

See also

References

- "Population and growth components (1851-2001 Censuses)." Statistics Canada (2005). Government of Canada. Archived from the original 8 January 2008.

- "2019 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration, for the period ending December 31, 2018, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada" accessed 2nd January, 2021

- "Right of Passage." Moving Here, Staying Here: The Canadian Immigrant Experience. Library and Archives Canada. 2006.

- Impressions: 250 Years of Printing in the Lives of Canadians Archived 2006-10-13 at the Wayback Machine, URL accessed 26 November 2006

- Impressions: The NDSU Libraries: Germans From Russia Archived 2006-12-09 at the Wayback Machine, URL accessed 26 November 2006

- Imp Homestead Act of 1862, URL accessed 26 November 2006

- Home Page – Town of Davidson, URL accessed 26 November 2006

- Saskatchewan Gen Web Project – SGW – Saskatchewan Genealogy Roots, URL accessed 26 November 2006

- First Nation Land Surrenders on the Prairies 1896–1911 Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine Peggy Martin-McGuire, Ch 2, Land and Colonization Companies, Indian Claims Commission, URL accessed January 11, 2007.

- Johnston, Hugh J.M., The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: the Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar. (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1979), p. 26

- "Why immigrants flock to Canada?". Immiboards.com. Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- "The History of Canada and Canadians – Colonies Grow Up". Linksnorth.com. 2006-10-12. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- Archived December 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-16. Retrieved 2018-04-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- David Smith, Instilling British Values in the Prairie Provinces", Prairie Forum 6#2 (1981): pp. 129–41.

- Kent Fedorowich, "Restocking the British World: Empire Migration and Anglo-Canadian Relations, 1919–30," Britain and the World (Aug 2016) 9#2 pp 236-269, DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3366/brw.2016.0239 open access

- Janice Cavell, "The Imperial Race and the Immigration Sieve: The Canadian Debate on Assisted British Migration and Empire Settlement, 1900–30", Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 34#3 (2006): pp. 345–67.

- Kurt Korneski, "Britishness, Canadianness, Class, and Race: Winnipeg and the British World, 1880s–1910s", Journal of Canadian Studies 41#2 (2007): pp. 161–84.

- Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship. "History of citizenship legislation - Canada.ca". www.canada.ca. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship. "Changes to the Citizenship Act as a Result of Bill C-6 - Canada.ca". www.canada.ca. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

Statistics Canada – immigration from 1851 to 2001

Further reading

- Kelley, Ninette; Trebilcock, Michael J. (2010), The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (2nd ed.), University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-9536-7

- DeRocco, John F. Chabot (2008), From Sea to Sea to Sea: A Newcomer's Guide to Canada, Full Blast Productions, ISBN 978-0-9784738-4-6

- Driedger, Leo; Halli, Shivalingappa S. (1999), Immigrant Canada: demographic, economic, and social challenges, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-4276-7

- Horner, Dan (2013). "'If the Evil Now Growing around Us Be Not Staid': Montreal and Liverpool Confront the Irish Famine Migration as a Transnational Crisis in Urban Governance". Histoire Sociale/Social History. 46 (92): 349–66 – via Project MUSE: 534564.

- Moens, Alexander; Collacott, Martin (2008), Immigration policy and the terrorist threat in Canada and the United States, Fraser Institute, ISBN 978-0-88975-235-1

- Powell, John (2005), Encyclopedia of North American immigration, Facts On File, ISBN 978-0-8160-4658-4

- Walker, Barrington (2008), The History of Immigration and Racism in Canada: Essential Readings, Canadian Scholars' Press, ISBN 978-1-55130-340-6

External links

- Historical population and migration statistical data - Statistics Canada (Archived)

- Multicultural Canada website

- Census Canada, Library and Archives

- Immigration Canada, Library and Archives

- Vital Statistics: Births, Marriages and Deaths

- Names of Emigrants (to Canada from Britain), From the 1845-1847 Records of James Allison, Emigrant Agent at Montreal