Hydraulic conductivity

Hydraulic conductivity, symbolically represented as , is a property of vascular plants, soils and rocks, that describes the ease with which a fluid (usually water) can move through pore spaces or fractures. It depends on the intrinsic permeability of the material, the degree of saturation, and on the density and viscosity of the fluid. Saturated hydraulic conductivity, Ksat, describes water movement through saturated media. By definition, hydraulic conductivity is the ratio of velocity to hydraulic gradient indicating permeability of porous media.

Methods of determination

There are two broad categories of determining hydraulic conductivity:

- Empirical approach by which the hydraulic conductivity is correlated to soil properties like pore size and particle size (grain size) distributions, and soil texture

- Experimental approach by which the hydraulic conductivity is determined from hydraulic experiments using Darcy's law

The experimental approach is broadly classified into:

- Laboratory tests using soil samples subjected to hydraulic experiments

- Field tests (on site, in situ) that are differentiated into:

- small scale field tests, using observations of the water level in cavities in the soil

- large scale field tests, like pump tests in wells or by observing the functioning of existing horizontal drainage systems.

The small scale field tests are further subdivided into:

- infiltration tests in cavities above the water table

- slug tests in cavities below the water table

The methods of determination of hydraulic conductivity and other related issues are investigated by several researchers.

Estimation by empirical approach

Estimation from grain size

Allen Hazen derived an empirical formula for approximating hydraulic conductivity from grain size analyses:

where

- Hazen's empirical coefficient, which takes a value between 0.0 and 1.5 (depending on literatures), with an average value of 1.0. A.F. Salarashayeri & M. Siosemarde give C as usually taken between 1.0 and 1.5, with D in mm and K in cm/s.

- is the diameter of the 10 percentile grain size of the material

Pedotransfer function

A pedotransfer function (PTF) is a specialized empirical estimation method, used primarily in the soil sciences, however has increasing use in hydrogeology.[1] There are many different PTF methods, however, they all attempt to determine soil properties, such as hydraulic conductivity, given several measured soil properties, such as soil particle size, and bulk density.

Determination by experimental approach

There are relatively simple and inexpensive laboratory tests that may be run to determine the hydraulic conductivity of a soil: constant-head method and falling-head method.

Constant-head method

The constant-head method is typically used on granular soil. This procedure allows water to move through the soil under a steady state head condition while the volume of water flowing through the soil specimen is measured over a period of time. By knowing the volume of water measured in a time , over a specimen of length and cross-sectional area , as well as the head , the hydraulic conductivity, , can be derived by simply rearranging Darcy's law:

Proof: Darcy's law states that the volumetric flow depends on the pressure differential, , between the two sides of the sample, the permeability, , and the viscosity, , as: [2]

In a constant head experiment, the head (difference between two heights) defines an excess water mass, , where is the density of water. This mass weighs down on the side it is on, creating a pressure differential of , where is the gravitational acceleration. Plugging this directly into the above gives

If the hydraulic conductivity is defined to be related to the hydraulic permeability as

- ,

this gives the result.'

Falling-head method

In the falling-head method, the soil sample is first saturated under a specific head condition. The water is then allowed to flow through the soil without adding any water, so the pressure head declines as water passes through the specimen. The advantage to the falling-head method is that it can be used for both fine-grained and coarse-grained soils. .[3] If the head drops from to in a time , then the hydraulic conductivity is equal to

Proof: As above, Darcy's law reads

The decrease in volume is related to the falling head by . Plugging this relationship into the above, and taking the limit as , the differential equation

has the solution

- .

Plugging in and rearranging gives the result.

In-situ (field) methods

In compare to laboratory method, field methods gives the most reliable information about the permeability of soil with minimum disturbances. In laboratory methods, the degree of disturbances affect the reliability of value of permeability of the soil.

Pumping Test

Pumping test is the most reliable method to calculate the coefficient of permeability of a soil. This test is further classified into Pumping in test and pumping out test.

Augerhole method

There are also in-situ methods for measuring the hydraulic conductivity in the field.

When the water table is shallow, the augerhole method, a slug test, can be used for determining the hydraulic conductivity below the water table.

The method was developed by Hooghoudt (1934)[4] in The Netherlands and introduced in the US by Van Bavel en Kirkham (1948).[5]

The method uses the following steps:

- an augerhole is perforated into the soil to below the water table

- water is bailed out from the augerhole

- the rate of rise of the water level in the hole is recorded

- the -value is calculated from the data as:[6]

where: horizontal saturated hydraulic conductivity (m/day), depth of the waterlevel in the hole relative to the water table in the soil (cm), at time , at time , time (in seconds) since the first measurement of as , and is a factor depending on the geometry of the hole:

where: radius of the cylindrical hole (cm), is the average depth of the water level in the hole relative to the water table in the soil (cm), found as , and is the depth of the bottom of the hole relative to the water table in the soil (cm).

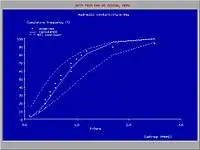

The picture shows a large variation of -values measured with the augerhole method in an area of 100 ha.[7] The ratio between the highest and lowest values is 25. The cumulative frequency distribution is lognormal and was made with the CumFreq program.

Related magnitudes

Transmissivity

The transmissivity is a measure of how much water can be transmitted horizontally, such as to a pumping well.

- Transmissivity should not be confused with the similar word transmittance used in optics, meaning the fraction of incident light that passes through a sample.

An aquifer may consist of soil layers. The transmissivity for horizontal flow of the soil layer with a saturated thickness and horizontal hydraulic conductivity is:

Transmissivity is directly proportional to horizontal hydraulic conductivity and thickness . Expressing in m/day and in m, the transmissivity is found in units m2/day.

The total transmissivity of the aquifer is:[6]

- where signifies the summation over all layers .

The apparent horizontal hydraulic conductivity of the aquifer is:

where , the total thickness of the aquifer, is , with .

The transmissivity of an aquifer can be determined from pumping tests.[8]

Influence of the water table

When a soil layer is above the water table, it is not saturated and does not contribute to the transmissivity. When the soil layer is entirely below the water table, its saturated thickness corresponds to the thickness of the soil layer itself. When the water table is inside a soil layer, the saturated thickness corresponds to the distance of the water table to the bottom of the layer. As the water table may behave dynamically, this thickness may change from place to place or from time to time, so that the transmissivity may vary accordingly.

In a semi-confined aquifer, the water table is found within a soil layer with a negligibly small transmissivity, so that changes of the total transmissivity () resulting from changes in the level of the water table are negligibly small.

When pumping water from an unconfined aquifer, where the water table is inside a soil layer with a significant transmissivity, the water table may be drawn down whereby the transmissivity reduces and the flow of water to the well diminishes.

Resistance

The resistance to vertical flow () of the soil layer with a saturated thickness and vertical hydraulic conductivity is:

Expressing in m/day and in m, the resistance () is expressed in days.

The total resistance () of the aquifer is:[6]

where signifies the summation over all layers:

The apparent vertical hydraulic conductivity () of the aquifer is:

where is the total thickness of the aquifer: , with

The resistance plays a role in aquifers where a sequence of layers occurs with varying horizontal permeability so that horizontal flow is found mainly in the layers with high horizontal permeability while the layers with low horizontal permeability transmit the water mainly in a vertical sense.

Anisotropy

When the horizontal and vertical hydraulic conductivity ( and ) of the soil layer differ considerably, the layer is said to be anisotropic with respect to hydraulic conductivity.

When the apparent horizontal and vertical hydraulic conductivity ( and ) differ considerably, the aquifer is said to be anisotropic with respect to hydraulic conductivity.

An aquifer is called semi-confined when a saturated layer with a relatively small horizontal hydraulic conductivity (the semi-confining layer or aquitard) overlies a layer with a relatively high horizontal hydraulic conductivity so that the flow of groundwater in the first layer is mainly vertical and in the second layer mainly horizontal.

The resistance of a semi-confining top layer of an aquifer can be determined from pumping tests.[8]

When calculating flow to drains[9] or to a well field[10] in an aquifer with the aim to control the water table, the anisotropy is to be taken into account, otherwise the result may be erroneous.

Relative properties

Because of their high porosity and permeability, sand and gravel aquifers have higher hydraulic conductivity than clay or unfractured granite aquifers. Sand or gravel aquifers would thus be easier to extract water from (e.g., using a pumping well) because of their high transmissivity, compared to clay or unfractured bedrock aquifers.

Hydraulic conductivity has units with dimensions of length per time (e.g., m/s, ft/day and (gal/day)/ft² ); transmissivity then has units with dimensions of length squared per time. The following table gives some typical ranges (illustrating the many orders of magnitude which are likely) for K values.

Hydraulic conductivity (K) is one of the most complex and important of the properties of aquifers in hydrogeology as the values found in nature:

- range over many orders of magnitude (the distribution is often considered to be lognormal),

- vary a large amount through space (sometimes considered to be randomly spatially distributed, or stochastic in nature),

- are directional (in general K is a symmetric second-rank tensor; e.g., vertical K values can be several orders of magnitude smaller than horizontal K values),

- are scale dependent (testing a m³ of aquifer will generally produce different results than a similar test on only a cm³ sample of the same aquifer),

- must be determined indirectly through field pumping tests, laboratory column flow tests or inverse computer simulation, (sometimes also from grain size analyses), and

- are very dependent (in a non-linear way) on the water content, which makes solving the unsaturated flow equation difficult. In fact, the variably saturated K for a single material varies over a wider range than the saturated K values for all types of materials (see chart below for an illustrative range of the latter).

Ranges of values for natural materials

Table of saturated hydraulic conductivity (K) values found in nature

Values are for typical fresh groundwater conditions — using standard values of viscosity and specific gravity for water at 20 °C and 1 atm. See the similar table derived from the same source for intrinsic permeability values.[11]

| K (cm/s) | 10² | 101 | 100=1 | 10−1 | 10−2 | 10−3 | 10−4 | 10−5 | 10−6 | 10−7 | 10−8 | 10−9 | 10−10 |

| K (ft/day) | 105 | 10,000 | 1,000 | 100 | 10 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 10−5 | 10−6 | 10−7 |

| Relative Permeability | Pervious | Semi-Pervious | Impervious | ||||||||||

| Aquifer | Good | Poor | None | ||||||||||

| Unconsolidated Sand & Gravel | Well Sorted Gravel | Well Sorted Sand or Sand & Gravel | Very Fine Sand, Silt, Loess, Loam | ||||||||||

| Unconsolidated Clay & Organic | Peat | Layered Clay | Fat / Unweathered Clay | ||||||||||

| Consolidated Rocks | Highly Fractured Rocks | Oil Reservoir Rocks | Fresh Sandstone | Fresh Limestone, Dolomite | Fresh Granite | ||||||||

Source: modified from Bear, 1972

See also

- Aquifer test

- Hydraulic analogy

- Pedotransfer function – for estimating hydraulic conductivities given soil properties

References

- Wösten, J.H.M., Pachepsky, Y.A., and Rawls, W.J. (2001). "Pedotransfer functions: bridging the gap between available basic soil data and missing soil hydraulic characteristics". Journal of Hydrology. 251 (3–4): 123–150. Bibcode:2001JHyd..251..123W. doi:10.1016/S0022-1694(01)00464-4.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Controlling capillary flow an application of Darcy's law

- Liu, Cheng "Soils and Foundations." Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2001 ISBN 0-13-025517-3

- S.B.Hooghoudt, 1934, in Dutch. Bijdrage tot de kennis van enige natuurkundige grootheden van de grond. Verslagen Landbouwkundig Onderzoek No. 40 B, p. 215-345.

- C.H.M. van Bavel and D. Kirkham, 1948. Field measurement of soil permeability using auger holes. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. Proc 13:90-96.

- Determination of the Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity. Chapter 12 in: H.P.Ritzema (ed., 1994) Drainage Principles and Applications, ILRI Publication 16, p.435-476. International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement, Wageningen (ILRI), The Netherlands. ISBN 90-70754-33-9. Free download from: , under nr. 6, or directly as PDF :

- Drainage research in farmers' fields: analysis of data. Contribution to the project “Liquid Gold” of the International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands. Free download from : , under nr. 2, or directly as PDF :

- J.Boonstra and R.A.L.Kselik, SATEM 2002: Software for aquifer test evaluation, 2001. Publ. 57, International Institute for Land reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands. ISBN 90-70754-54-1 On line :

- The energy balance of groundwater flow applied to subsurface drainage in anisotropic soils by pipes or ditches with entrance resistance. International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement, Wageningen, The Netherlands. On line: Archived 2009-02-19 at the Wayback Machine . Paper based on: R.J. Oosterbaan, J. Boonstra and K.V.G.K. Rao, 1996, “The energy balance of groundwater flow”. Published in V.P.Singh and B.Kumar (eds.), Subsurface-Water Hydrology, p. 153-160, Vol.2 of Proceedings of the International Conference on Hydrology and Water Resources, New Delhi, India, 1993. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. ISBN 978-0-7923-3651-8. On line: . The corresponding free EnDrain program can be downloaded from:

- Subsurface drainage by (tube)wells, 9 pp. Explanation of equations used in the WellDrain model. International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands. On line: . The corresponding free WellDrain program can be downloaded from :

- Bear, J. (1972). Dynamics of Fluids in Porous Media. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-65675-6.