Jurassic National Monument

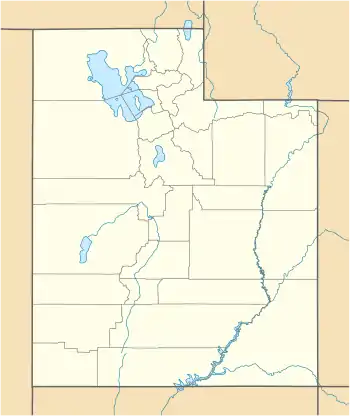

Jurassic National Monument, at the site of the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, well known for containing the densest concentration of Jurassic dinosaur fossils ever found, is a paleontological site located near Cleveland, Utah, in the San Rafael Swell, a part of the geological layers known as the Morrison Formation.

| Jurassic National Monument | |

|---|---|

Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry Visitor Center | |

Map of Utah | |

| Location | Emery County, Utah |

| Nearest city | Cleveland |

| Coordinates | 39.32282°N 110.68951°W |

| Governing body | Bureau of Land Management |

| www | |

| Designated | 1965 |

Well over 15,000 bones have been excavated from this Jurassic excavation site and there are many thousands more awaiting excavation and study. It was designated a National Natural Landmark in October 1965.[1] The John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, signed into law March 12, 2019, named it as a national monument.[2]

All of these bones, belonging to different species, are found disarticulated and indistinctly mixed together. It has been hypothesised that this strong concentration of mixed fossilised bones is due to a "predator trap", but any kind of definitive scientific consensus hasn't been reached yet and debates still continue to the present day.

Visiting

The visitor center is administered by the Bureau of Land Management. There is a skeleton reconstruction of an adult Allosaurus (and other bones) on display in the visitor center, along with many other exhibits. A renovated and expanded quarry visitor center was dedicated on April 28, 2007. The visitor center is open seasonally with variable hours.

History

The quarry was found by sheepherders and cattlemen as they drove their animals through the area during the late 19th century. In 1927, the Department of Geology at the University of Utah, under the direction of Chairman F.F. Hintze, visited the area and collected 800 bones. In 1939-41 a field party of Princeton University, led by William Lee Stokes (1915-1994, known as the "Father of Utah geology"), came on site to extensively dig up specimens. Because of the proximity to Cleveland, Utah, and because these expeditions were financed by Malcolm Lloyd, the site was later known as the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry.[3] In three summers, the 1939-1941 Princeton expeditions collected 1,200 bones. A part of these bones was sent to Princeton and eventually the bones were sorted to mount a complete composite skeleton of Allosaurus, but World World II broke out and the skeleton was not really mounted and exhibited in the University until February 1961. This Allosaurus skeleton, still nowadays on display at Guyot Hall, in the campus of New Jersey, is most likely the first Allosaurus skeletal mount obtained from the Quarry. In the meantime, and because excavations had been interrupted by the war, work started again in 1960, when young paleontologist James Henry Madsen Jr. (1932-2009) was hired within the University of Utah to assist William Lee Stokes with the excavations.

As of 1960 Stokes and Madsen founded the "University of Utah Cooperative Dinosaur Project",[4] with funds of the University of Utah. This project granted casts or specimens of dinosaurs to museums and institutions from the USA but also from countries all around the world, in exchange of financial and excavation assistance.[4] The project continued until 1976 when the University of Utah interrupted the funding. Madsen managed to continue excavating the Quarry by means of a private company he founded the same year, Dinolab, intended to sell casts of dinosaur skeletons to museums, institutions and private buyers. Before that, in 1974, a new dinosaur had been described by Madsen, then Assistant Research Professor of Geology and Geophysics in the University of Utah. He named it Stokesosaurus clevelandi, honouring his mentor, professor William Lee Stokes. In 1976, another new dinosaur was described from fossils found in the quarry by Madsen. He named it Marshosaurus bicentesimus, honouring American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh (1831-1899). In 1987, Brigham Young University paleontologists excavated a fossil dinosaur egg, at the time the oldest such egg ever found.

Over the years, excavations led by the University of Utah and the Natural History Museum of Utah have resulted in the collection of more than 12,000 fossil bones from the quarry. While most of the original fossils are currently housed at the Natural History Museum of Utah, many skeletons reproduced from Cleveland-Lloyd dinosaur remains are now on exhibit in more than 65 museums worldwide. Original specimens from the quarry remain on public exhibit in Utah at the Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City, the Utah State University Eastern Prehistoric Museum[5] in Price and the Earth Science Museum at Brigham Young University in Provo.

The U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) opened a visitor center at the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry in 1968. This was the first-ever BLM visitor center. On April 28, 2007 a new, larger facility was dedicated that has updated exhibits. The new visitor center generates its own electricity from rooftop solar panels.

Early in 2019, the quarry reached the official status of "national monument" under the name of "Jurassic National Monument".[6][7]

Geology

The Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry of east central Utah has produced one of the most prolific dinosaurs bone assemblages in the Upper Jurassic beds of North America. The quarry is part of the Brushy Basin Member of the Morrison Formation. The fossil deposit, which is interpreted to be a possible predator trap, consists of a calcareous smectitic mudstone which accumulated on the floodplain of an anastomosing river system. An anastomosing river system consists of multiple interconnected channels confined by prominent levees separated by interchannel topographic lows. The depositional environment of the quarry mudstone was an interchannel seasonal accumulation of clay nested in a topographic low between channel levees called a floodpond.

Dinosaurs became entrapped in the cohesive and adhesive mud as they drank and hunted near the floodpond. The preserved fauna consists of almost all dinosaurs with the majority being carnivorous dinosaurs including Allosaurus (material from at least 44 individuals make up almost 67% of all remains), Torvosaurus (1), Ceratosaurus (1), Stokesosaurus (2), Marshosaurus (2), and possibly an Ornitholestes. Herbivorous dinosaurs include Camarasaurus (5), Haplocanthosaurus (1), Barosaurus (1), Amphicoelias (1), Mongolosaurus (1), an unidentified sauropod, Camptosaurus (5), Stegosaurus (4), a possible ankylosaur (1), and an unidentified ornithopod. Non-dinosaurian fauna include a crocodile (Goniopholis), 2 turtles (Glyptops), 4 genera of gastropoda (snails), and 4 genera of charophyte.

The atypical predator/prey ratio (3:1) represented at the quarry may be explained by pack hunting tendencies of Allosaurus. The high percentage of smaller individual allosaurs suggests that juveniles coordinated their efforts to capture and kill prey. They may have followed their prey into the floodpond and subsequently became mired themselves. The close spatial proximity of skull elements (most belonging to Allosaurus) supports this hypothesis. Larger individual theropods almost certainly became mired while attempting to scavenge the carcasses of other entrapped dinosaurs (Richmond and Morris, 1996). However, some palaeontologists suggest that the mass deaths were in fact a result of a drought, and not a predator trap. One comparison with the La Brea Tar Pits suggest that multiple, non-migratory groups of Allosaurus may have come to the area looking to find water, dying due to the harsh conditions and perhaps from diseases caused by drinking contaminated water due to rotting carcasses and feces being present. The evidence for this theory is strengthened by the fact that a large proportion of the Allosaurus specimens are juveniles, but until more evidence is recovered, this cannot yet be vindicated.[8] Debates continue to this day.

Paleofauna

Fossil taxa discovered at the Cleveland-Lloyd site include:

Plantae

- Thallophyta

- Aclistochara

- Latochara

- Stellatochara

Dinosauria

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

Ornithischians

| Ornithischians reported from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Notes | Images | |||

|

C. dispar |

||||||

|

S. stenops |

The largest ornithischian reported from the quarry | |||||

Sauropods

| Sauropods reported from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Notes | Images | |||

|

A. sp |

||||||

|

B. sp |

||||||

|

C. lentus |

3 skeletons were unearthed |

|||||

Theropods

| Theropods reported from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Amount | Notes | Images | ||

|

A. fragilis |

44 - 60 |

The largest theropod reported from the quarry |

Allosaurus mounted skeleton | |||

|

C. nasicornis |

1 |

The rarest theropod species in the quarry | ||||

|

M. bicentesimus |

2 |

|||||

|

S. clevelandi |

3 |

The largest coelurosaur reported from the quarry | ||||

|

T. topwilsoni |

1 |

Remains originally referred to Stokesosaurus clevelandi. | ||||

See also

- La Brea tar pits

- List of dinosaur-bearing rock formations

- Predator trap

References

- "National Natural Landmarks - National Natural Landmarks (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-30.

Year designated: 1965

- "Text - S.47 - John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act". United States Congress. 2019-03-12. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "Cleveland Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry". Utah.com. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- James H. Madsen. Allosaurus fragilis: a revised osteology.

- http://144.39.2.208/museum/

- Alejandra Borunda, "10 places that will be protected by Congress’s new public lands bill : A sweeping package protects over two million acres across the U.S.", National Geographic, 27 February 2019

- Katharine Gammon, "Trump approves five national monuments – from black history to dinosaur bones", The Guardian, 12 March 2019

- https://commons.lib.niu.edu/bitstream/handle/10843/21602/Reddick_niu_0162M_13209.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y&fbclid=IwAR05rJbQ5h7juSLs-CattCrBGV48VtWR6pnsouWC7CIj9IJ8MQt55dymmnc

Other sources

- Stokes, William J. (1945). A new quarry for Jurassic dinosaurs. Science. 101 (2614): 115–117. Bibcode:1945Sci...101..115S

- Stokes, W. L. (1985). The Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry: Window to the Past. U. S. Government Printing Office.

- Richmond, D. R. and Morris, T. H. (1996). The dinosaur death trap of the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Emery County, Utah, in Morales, M., ed., The Continental Jurassic: Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 60, pp. 533–545.

- Joseph E. Peterson, Jonathan P. Warnock, Shawn L. Eberhart, Steven R. Clawson & Christopher R. Noto (2017). New data towards the development of a comprehensive taphonomic framework for the Late Jurassic Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Central Utah. PeerJ 5:e3368, doi: http://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3368

- Hunt, Adrian P; Lucas, Spencer G.; Krainer, Karl; Spielmann, Justin (2006). The taphonomy of the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, Utah: a re-evaluation. In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 57–65.

- Loewen, Mark A. (2003). Morphology, taxonomy, and stratigraphy of Allosaurus from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (3, Suppl.): 72A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2003.10010538

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jurassic National Monument. |