Fort McHenry

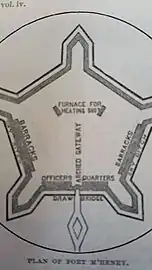

Fort McHenry is a historical American coastal pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attack by the British navy from the Chesapeake Bay on September 13–14, 1814. It was first built in 1798 and was used continuously by the U.S. armed forces through World War I and by the Coast Guard in World War II. It was designated a national park in 1925, and in 1939 was redesignated a "National Monument and Historic Shrine".

| Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Location | Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 39°15′47″N 76°34′48″W |

| Area | 43.26 acres (17.51 ha)[1] |

| Authorized | March 3, 1925 |

| Visitors | 635,736 (in 2018)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine |

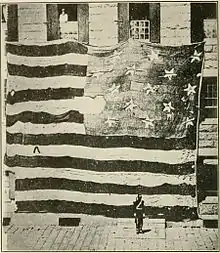

During the War of 1812 an American storm flag, 17 by 25 feet (5.2 m × 7.6 m), was flown over Fort McHenry during the bombardment. It was replaced early on the morning of September 14, 1814 with a larger American garrison flag, 30 by 42 feet (9.1 m × 12.8 m). The larger flag signaled American victory over the British in the Battle of Baltimore. The sight of the ensign inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem "Defence of Fort M'Henry" that was later set to the tune "To Anacreon in Heaven" and became known as "The Star Spangled Banner", the national anthem of the United States.

History

18th Century

Fort McHenry was built on the site of the former Fort Whetstone, which had defended Baltimore from 1776 to 1797. Fort Whetstone stood on Whetstone Point (today's residential and industrial area of Locust Point) peninsula, which juts into the opening of Baltimore Harbor between the Basin (today's Inner Harbor) and Northwest branch on the north side and the Middle and Ferry (now Southern) branches of the Patapsco River on the south side.

The Frenchman Jean Foncin designed the fort in 1798,[3] and it was built between 1798 and 1800. The new fort's purpose was to improve the defenses of the increasingly important Port of Baltimore from future enemy attacks.

The new fort was a bastioned pentagon, surrounded by a dry moat—a deep, broad trench. The moat would serve as a shelter from which infantry might defend the fort from a land attack.[4] In case of such an attack on this first line of defense, each point, or bastion could provide a crossfire of cannon and small arms fire.

Fort McHenry was named after early American statesman James McHenry (1753–1816), a Scots-Irish immigrant and surgeon-soldier. He was a delegate to the Continental Congress from Maryland and a signer of the United States Constitution. Afterwards, he was appointed United States Secretary of War (1796–1800), serving under Presidents George Washington and John Adams.

War of 1812

Beginning at 6:00 a.m. on September 13, 1814, British warships under the command of Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane continuously bombarded Fort McHenry for 25 hours.[5] The American defenders had 18-, 24- and 32-pounder (8, 11, and 16 kg) cannons. The British guns had a range of 2 miles (3 km), and the British rockets had a 1.75-mile (2.8 km) range, but neither guns nor rockets were accurate. The British ships were unable to pass Fort McHenry and penetrate Baltimore Harbor because of its defenses, including a chain of 22 sunken ships, and the American cannons. The British vessels were only able to fire their rockets and mortars at the fort at the weapons' maximum range. The poor accuracy on both sides resulted in very little damage to either side before the British, having depleted their ammunition, ceased their attack on the morning of September 14.[6] Thus the naval part of the British invasion of Baltimore had been repulsed. Only one British warship, a bomb vessel, received a direct hit from the fort's return fire, which wounded one crewman.

The Americans, under the command of Major George Armistead, lost four killed—including one Black soldier, Private William Williams, and a woman who was cut in half by a bomb as she carried supplies to the troops—and 24 wounded. At one point during the bombardment, a bomb crashed through the fort's powder magazine. However, either the rain extinguished the fuse or the bomb was a dud.[7]

Star Spangled Banner

Francis Scott Key, a Washington lawyer who had come to Baltimore to negotiate the release of Dr. William Beanes, a civilian prisoner of war, witnessed the bombardment from a nearby truce ship. An oversized American flag had been sewn by Mary Pickersgill for $405.90[9] in anticipation of the British attack on the fort. When Key saw the flag emerge intact in the dawn of September 14,[6] he was so moved that he began that morning to compose "Defence of Fort M'Henry" set to the tune "To Anacreon in Heaven" which would later be renamed "The Star-Spangled Banner" and become the United States' national anthem.

Civil War

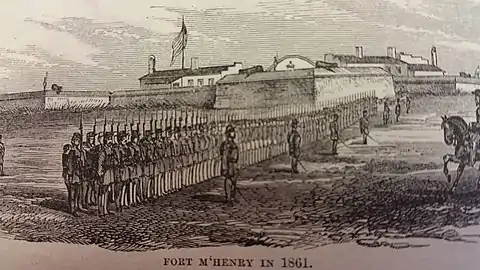

During the American Civil War the area where Fort McHenry sits served as a military prison, confining both Confederate soldiers, as well as a large number of Maryland political figures who were suspected of being Confederate sympathizers. The imprisoned included newly elected Baltimore Mayor George William Brown, the city council, and the new police commissioner, George P. Kane, and members of the Maryland General Assembly along with several newspaper editors and owners. Francis Scott Key's grandson, Francis Key Howard, was one of these political detainees. Some of the cells used still exist and can be visited at the fort. Fort McHenry also served to train artillery at this time; this service is the origin of the Rodman guns presently located and displayed at the fort.

On 25 May 1861 John Merryman was arrested in Baltimore County and imprisoned in Fort McHenry. Merryman had had a role in destroying bridges in Maryland to impede the movement of Union troops. Merryman petitioned Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney for a writ of habeas corpus, and Taney granted the petition, demanding that Merryman appear in his courtroom the next day and sending U.S. Marshals to the fort to enforce the ruling. A famous and dramatic standoff then occurred at the gates of the fort between the Federal Marshals and General George Cadwalader, the commander of Union troops of the Fort. The commander refused to comply with the order on the grounds that he was acting under orders from President Abraham Lincoln, who had suspended habeas corpus. The court case, Ex parte Merryman, remains unresolved, and the Executive Branch continued to refuse to comply with Taney's ruling.

World War I

During World War I, an additional hundred-odd buildings were built on the land surrounding the fort in order to convert the entire facility into an enormous U.S. Army hospital for the treatment of troops returning from the European conflict. None of those buildings remain, while the original fort has been preserved and restored to essentially its condition during the War of 1812.[10]

World War II

During World War II, Fort McHenry served as a Coast Guard base.[10] Used for training, the historic sections remained open to the public.

National monument

The fort was made a national park in 1925; on August 11, 1939, it was redesignated a "National Monument and Historic Shrine", the only such doubly designated place in the United States. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. It has become national tradition that when a new flag is designed it first flies over Fort McHenry. The first official 49- and 50-star American flags were flown over the fort and are still located on the premises.[11][12]

Today

The fort has become a center of recreation for the Baltimore locals as well as a prominent tourist destination. Thousands of visitors come each year to see the "Birthplace of the Star Spangled Banner." It's easily accessible by water taxi from the popular Baltimore Inner Harbor. However, to prevent abuse of the parking lots at the Fort, the National Park Service does not permit passengers to take the water taxi back to the Inner Harbor unless they have previously used it to arrive at the monument.[13]

Several authorized archaeological digs have been conducted, and found artifacts are on display in one of the buildings surrounding the Parade Ground. These structures, as well as the Visitor Center, have numerous other exhibits as well that show the fort's use over time.

Every September, the City of Baltimore commemorates Defenders Day in honor of the Battle of Baltimore. It is the biggest celebration of the year at the Fort, accompanied by a weekend of programs, events, and fireworks.

In 2005 the living history volunteer unit, the Fort McHenry Guard, was awarded the George B. Hartzog award for serving the National Park Service as the best volunteer unit. Among the members of the unit is Martin O'Malley, the former mayor of Baltimore and Governor of Maryland, who was made the unit's honorary colonel in 2003.

The flag that flew over Fort McHenry, the Star Spangled Banner Flag, has deteriorated to an extremely fragile condition. After undergoing restoration at the National Museum of American History, it is now on display there in a special exhibit that allows it to lie at a slight angle in dim light.[14]

The United States Code currently authorizes Fort McHenry's closure to the public in the event of a national emergency for use by the military for the duration of such an emergency.[15]

In 2013, Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine was honored with its own quarter under the America the Beautiful Quarters Program.

On September 10–16, 2014, Fort McHenry celebrated the bicentennial of the writing of the Star Spangled Banner called the Star Spangled Spectacular. The event included a parade of tall ships, a large fireworks show, and the Navy's Blue Angels[16]

As of 2015, restoration efforts began to preserve the original brick used in construction of the Fort, primarily through mortar replacement.[17]

On August 26, 2020, when due to the Coronacrisis a normal Republican National Convention could not be held, vice president Mike Pence held his acceptance speech after being nominated for a second term as vice president of the United States at Fort McHenry.

Gallery

Historical re-enactment at Fort McHenry

Historical re-enactment at Fort McHenry The sally port (main entrance) into Fort McHenry.

The sally port (main entrance) into Fort McHenry. Adjacent to Fort McHenry lies a monument of Orpheus that is dedicated to the soldiers of the fort and Francis Scott Key.

Adjacent to Fort McHenry lies a monument of Orpheus that is dedicated to the soldiers of the fort and Francis Scott Key. Fort McHenry[18]

Fort McHenry[18] Fort McHenry map[18]:237

Fort McHenry map[18]:237

See also

- List of forts

- Fort McHenry Tunnel – opened 1985; passes a few hundred feet south of Fort McHenry and is part of Interstate 95

- List of Civil War POW Prisons and Camps

- List of National Monuments of the United States

References

- "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-05-13.

- "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-05-13.

- Kaufmann, J. E.; Idzikowski, Tomasz (2005). Fortress America. Da Capo Press. p. 144.

- "Rebuilding the Dry Moat". Fort McHenry Guard. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- George, Christopher T. (2000). Terror on the Chesapeake: The War of 1812 on the Bay. Shippensburg, Pa.: White Mane Books. pp. 145–148.

- "A Moment of Triumph". Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- "Fort McHenry". Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- "The Star-Spangled Banner, 1814".

- "The Star-Spangled Banner: Making the Flag". National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2009-10-05.

- Steve Whissen (October 1996). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Fort McHenry National Monument & Historic Shrine" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- "Robert G. Heft: Designer of America's Current National Flag". USFlag.org: A website dedicated to the Flag of the United States of America. Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- Rasmussen, Frederick N. (July 3, 2010). "A half-century ago, new 50-star American flag debuted in Baltimore". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-07-17. Retrieved 2015-08-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Interactive Flag". (color image of flag as it appears after preservation work)

- Elsea, Jennifer K.; Weed, Matthew C. (2011). Declarations of War and Authorizations for the Use of Military Force: Historical Background and Legal Implications (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service. p. 75. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-10.

- "Star Spangled 200". Star Spangled 200. Archived from the original on March 19, 2015.

- Knezevich, Alison (5 June 2015). "National parks maintenance backlog in Maryland tops $345 million". Baltimore Sun.

- Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 954.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article "Fort McHenry". |

- Official website

- Fort McHenry Guard

- British Attack on Ft. McHenry Launched from Bermuda

- Fort McHenry is part of the Chesapeake Bay Gateways and Watertrails Network

- Weather & Maps – Unearthed Outdoors

- Baltimore, Maryland, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Ft. McHenry on Google Street View

- 2008 Photo Feature

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. MD-63, "Fort McHenry National Monument & Historic Shrine, East Fort Avenue at Whetstone Point, Baltimore, Independent City, MD", 32 photos, 11 measured drawings, 78 data pages

- C-SPAN American History TV "Birth of the Star-Spangled Banner" Tour at Fort McHenry

- C-SPAN American History TV "After the Star-Spangled Banner" Tour at Fort McHenry