Marble Hill House

Marble Hill House is a Palladian villa built between 1724 and 1729 in Twickenham in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It was the home of Henrietta Howard, Countess of Suffolk, who lived there until her death. The compact design soon became famous and furnished a standard model for the Georgian English villa and for plantation houses in the American colonies.

| Marble Hill House | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) North (town) front, with pilasters | |

| Type | Villa |

| Location | Twickenham |

| Coordinates | 51°26′58″N 0°18′48″W |

| OS grid reference | TQ 17296 73627 |

| Area | Richmond upon Thames |

| Built | 1724–1729 |

| Architect | Roger Morris |

| Architectural style(s) | Palladian |

| Owner | English Heritage |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Marble Hill House |

| Designated | 2 September 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1285673 |

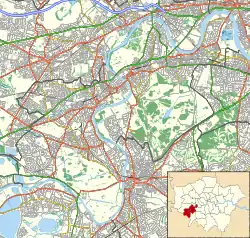

Location of Marble Hill House in London Borough of Richmond upon Thames | |

Description

Marble Hill House was built in 1724–1729 by Henrietta Howard, the mistress of King George II,[1] to the designs of the architect Roger Morris (1695–1749) in collaboration with Henry Herbert, 9th Earl of Pembroke, one of the "architect earls".

Pembroke, then Lord Herbert, based the design of Marble Hill to a large degree on Andrea Palladio's 1553 Villa Cornaro in Piombino Dese, Italy, and thus incorporated a cubic saloon on the first floor or piano nobile.[2] Villa Cornaro also served as a model for plantation houses in the American colonies, examples being Drayton Hall (1738–1742) in Charleston, South Carolina, and Thomas Jefferson's initial version of Monticello (1768–1770). It was in other respects an adaptation of a more expansive design by Colen Campbell. It is set in 66 acres (2.67 km²) of parkland known as Marble Hill Park. The Great Room contains lavishly gilded decoration and five capricci paintings by Giovanni Paolo Pannini. Marble Hill House also contains a loaned collection of early Georgian furniture and paintings as well as the Chinoiserie collection of the Lazenby Bequest.[3]

It was located a few miles away from Kendal House, another Palladian property built around the same time for a royal mistress, Melusine von der Schulenburg, Duchess of Kendal who had been the long-term lover of George I.

Both Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift were regular guests at the house during the lifetime of Henrietta Howard.

In the late 18th century the house was rented by the Prince Regent (the future king, George IV) for his mistress, Maria Fitzherbert, so the two could continue to meet in private.

Shortly after its building the architecture of Marble Hill House became widely known from published engravings, and was widely admired for its compact plan and tightly controlled elevations. Its design was soon copied elsewhere, rarely in the 1730s and 1740s[5] but more commonly thereafter, and provided a standard model for the English villas built throughout the Thames Valley and further afield, for example New Place, King's Nympton, Devon, built between 1746 and 1749 to the design of Francis Cartwright of Blandford in Dorset.[4]

An archeological investigation found evidence of what has been described as a bowling alley next to the house in 2017.[6] However, it is likely that game resembled boules as much as bowling and the "alley" (better described as a depression in the ground) does not resemble the modern concept of a bowling alley. The main evidence that the area was used for some sort of bowling rests on contemporary plans.

The house is now owned by English Heritage, which acquired it in 1986 following the abolition of the Greater London Council. Its extensive grounds are known as Marble Hill Park and provide many leisure facilities including rugby and hockey pitches, a cricket pitch and nets, tennis courts, and a children's play area.

In 2015, English Heritage won a Heritage Lottery Fund grant to develop Marble Hill House and its park in order to improve its presentation and the associated leisure facilities. As part of this project Historic England made a range of landscape investigations, including geophysical surveys, aerial photography and lidar mapping, analytical earthwork survey, coring and vegetation analysis to create a clear picture of the development of the Marble Hill landscape from the 17th century onwards.[7]

See also

- Marble Hill Park

- Yelverton Lodge – a hunting lodge across Richmond Road

Notes and references

- Marie P. G. Draper and W. A. Eden, Marble Hill House and its Owners 1970.

- RIBA "Palladio and Britain" Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- John Jacob and Elizabeth Einberg, Marble Hill House, Catalogue

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bridget Cherry, The Buildings of England: Devon, London, 2004, p.522

- Speaking of Chiswick, Marble Hill and Stourhead, "If we look round for imitations of these in the thirties and forties, there are not so very many", Sir John Summerson observed, (Architecture in Britain, 1530 to 1830 9th ed. "Palladian permutations: the villa", 1993:347).

- "A 250-year-old bowling alley has been discovered in Twickenham". Sutton and Croydon Guardian. 8 August 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Alexander, M; Carpenter, E (2017). "Marble Hill House, Twickenham, Greater London. Historic England Research Report 5/2017". research.historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 11 June 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Sources

- Bryant, Julius, Marble Hill (London: English Heritage, 2002)

- Bryant, Julius, Chinoiserie: the Rosemary and Monty Lazenby bequest presented through the National Art-Collections Fund to Marble Hill House.Marble Hill House (London: English Heritage, 1988)

- Bryant, Julius, London's country house collections (London: Scala Books in association with English Heritage, 1993)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marble Hill House. |