Milwaukee Formation

The Milwaukee Formation is a fossil-bearing geological formation of Middle Devonian age in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin. It stands out for the exceptional diversity of its fossil biota. Included are many kinds of marine protists, invertebrates, and fishes, as well as early trees and giant fungi.[1]

| Milwaukee Formation Stratigraphic range: Givetian | |

|---|---|

One meter vertical section of Milwaukee Formation at its type locality in Estabrook Park, Milwaukee County, Wisconsin. Vegetation is seen at disconformity between the Lindwurm and Berthelet Members. | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Sub-units | Ascending: Berthelet Member, Lindwurm Member, North Point Member |

| Thickness | 17-21 meters |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Argillaceous dolostone and shale |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | Type locality: 43.0985° N, 87.9057° W |

| Region | Northern Milwaukee County, Wisconsin |

| Country | United States |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Milwaukee, Wisconsin |

| Named by | W. C. Alden, 1906 |

Once a prolific source of fossils, the Milwaukee Formation exposures are now mostly buried, inaccessible, on private property, or located in areas where collecting is prohibited. Most of these exposures are or were located along the Milwaukee River and Lake Michigan shore.[1]

History and significance

Early interest in the Milwaukee Formation was mainly of a commercial or other practical nature. Strata apparently of what would later be known as the Milwaukee Formation[2] were utilized as early as the 1670s, when French visitors used “pitch” (natural asphalt) from the rock exposures on the shore of Lake Michigan near Milwaukee to patch their boats.[3] The rock was later used to produce lime or building stone, and in the 1840s, Wisconsin’s first resident scientist, Increase A. Lapham, noted the natural cement potential of certain of its layers. When calcined (heated to high temperatures) and crushed, cement was produced, without requiring additives or further processing. During that time, Lapham also collected fossils from those strata, which caught the attention of James Hall, Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin and other noted American paleontologists and geologists who went on to study the biota. In 1876, the Milwaukee Cement Company began manufacturing natural cement, and soon became one of the country’s largest natural cement producers. Quarrying methods at that time required many hands to load rock into the dump cars destined for the kilns. This hands-on method was the perfect way for fossils to be detected. Several wealthy businessmen and professionals interested in acquiring large fossil collections recognized this and paid the quarry workers to set aside the best fossils. This continued until about 1911, when the cement rock was depleted, Portland Cement replaced natural cement, and the quarries were closed. Many thousands of high quality fossils were obtained this way between 1876 and 1911 for the collections of Thomas A. Greene, Edgar E. Teller, and Charles E. Monroe, and these can now be studied in numerous museums around central and eastern United States and Canada, especially the Milwaukee Public Museum, the Greene Geological Museum (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee), the National Museum of Natural History, the Museum of Comparative Zoology, the Buffalo Museum of Science, the Field Museum of Natural History, Williams College, and the Royal Ontario Museum.[1]

The fossils found during and after that time indicate that the Milwaukee Formation contains one of the richest and most diverse biotas in North America coming from a single formation of its age (late Givetian), with about 250 species coming from around 100 families, at least sixteen phyla, and four kingdoms. The formation preserves fossils of marine and terrestrial organisms, including placoderm fish that were the size of great white sharks, some of the first trees, and fungi that may have reached the height of a two-story building.[1]

Geological setting

The Milwaukee Formation is considered to be Givetian in age (~385 mya), as determined by using its biota to correlate the strata with certain portions of the Cedar Valley Group to the west. This age determination is also consistent with the formation's placement above the Givetian Thiensville Formation and below the Frasnian to Famennian Antrim Shale.[1]

Stratigraphy

The Milwaukee Formation lies disconformably between the Thiensville Formation and Antrim Shale. It was apparently deposited in relatively shallow, subtidal, normal marine conditions.[1] It is divided into three members.[4]

North Point Member

The North Point Member is the youngest (highest) member. Its contact with the underlying Lindwurm Member is transitional. It is entirely sub-surface and known only from tunneling material and cores. It consists of dark gray mudstone, dolomitic mudstone, and thin layers of dolomitic siltstone with chert and silicified fossils. The fauna is dominated by chonetid brachiopods, large tentaculitids, and bivalves. Much of it appears to have been deposited in dysaerobic conditions.[5][1]

Lindwurm Member

The Lindwurm Member disconformably overerlies the Berthelet. It consists mainly of moderately to thinly-bedded, argillaceous dolostone and dolomitic siltstone or mudstone. It is extremely fossiliferous. Numerous thin layers of what appear to be storm deposits are composed largely of broken shells. Echinoderms and trilobites are more abundant and varied than in the other members.[5][1]

Berthelet Member

The Berthelet Member consists mainly of relatively heavily-bedded, argillaceous dolostone. The top beds are more dolomitic, thick-bedded, vuggy, and asphaltic than the lower ones. Most of the plant fossils and the majority of the fish come from this member. The top beds also contain more cephalopod fossils than elsewhere in the formation.[5][1]

Taphonomy

The fossils of the Milwaukee Formation are preserved in many different ways. Most of the shelly fossils in the Berthelet Member are preserved as internal molds and external molds, whereas most of those in the Lindwurm Member are permineralized to some degree. Many fossils in all three members are formed by replacement. The most frequent replacement minerals are marcasite followed by pyrite, which are generally weathered to ferrous sulfate or limonite, respectively. Chert is a common replacement mineral in certain layers of the North Point Member. Plant fossils in the Milwaukee Formation are usually coalified to some degree.[1]

Other taphonomic phenomena often found in the Milwaukee Formation are geodization of shelly fossils, corals, bryozoans, and echinoderms, and preservation of color patterns in certain brachiopods, trilobites, and fin spines of fish.[6][1]

Biota

The most distinctive feature of the Milwaukee Formation is the diversity of its biota, as measured by the total number of species. The most species-rich group of the Milwaukee Formation’s biota is the Brachiopoda, having around 46 named species and sub-species,[7] followed by the Bivalvia, which has around 43.[8] Those plus species and sub-species from the following groups of marine and terrestrial organisms comprise a total of approximately 250 species: agglutinated foraminifers, conulariids, rugose corals, tabulate corals, tentaculitids, microconchids, cornulitids, hyoliths, gastropods, rostroconches, nautiloids, actinoceratoids, ammonoids, polychaetes, phacopid trilobites, proetid trilobites, ostracods, phyllocarids, crinoids, blastoids, edrioasteroids, dendroid graptolites, conodonts, arthrodire placoderms, ptyctodont placoderms, rhenaniform placoderms, petalichthyiform placoderms, chondrichthyans, acanthodians, sarcopterygians, fungi, cladoxylopsids, and lycopods.[1]

Gallery

The conulariid scyphozoan Conularia milwaukeensis

The conulariid scyphozoan Conularia milwaukeensis

The tentaculitoid Tentaculites bellulus

The tentaculitoid Tentaculites bellulus The bryozoan Sulcoretepora

The bryozoan Sulcoretepora The bryozoan Eridotrypa

The bryozoan Eridotrypa The linguliform brachiopod Barroisella

The linguliform brachiopod Barroisella The rhynchonelliform brachiopod Tylothyris

The rhynchonelliform brachiopod Tylothyris The rhynchonelliform brachiopod Schizophoria

The rhynchonelliform brachiopod Schizophoria Striatochonetes and other brachiopods

Striatochonetes and other brachiopods The rhynchonelliform brachiopod Cranaena

The rhynchonelliform brachiopod Cranaena The gastropod Platyceras

The gastropod Platyceras The bivalve Mytilarca cingulosa

The bivalve Mytilarca cingulosa The nautiloid cephalopod Gyronaedyceras eryx

The nautiloid cephalopod Gyronaedyceras eryx The nautiloid cephalopod Acleistoceras whitfieldi

The nautiloid cephalopod Acleistoceras whitfieldi

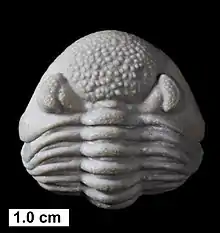

The proetid trilobite Crassiproetus

The proetid trilobite Crassiproetus The spiny, stalked crinoid Melocrinites nodosus spinosus

The spiny, stalked crinoid Melocrinites nodosus spinosus Crown of the crinoid Taxocrinus telleri

Crown of the crinoid Taxocrinus telleri Theca of the blastoid Hyperoblastus

Theca of the blastoid Hyperoblastus Edrioasteroid, possibly Krama or Agelacrinites, with dissociated ambulacral plates

Edrioasteroid, possibly Krama or Agelacrinites, with dissociated ambulacral plates Fin spine from the placoderm Eczematolepis

Fin spine from the placoderm Eczematolepis "Tooth" plates from the ptyctodont placoderm Ptyctodus ferox

"Tooth" plates from the ptyctodont placoderm Ptyctodus ferox Tooth from the sarcopterygian fish Onychodus

Tooth from the sarcopterygian fish Onychodus Bark from a possible cladoxylopsid tree

Bark from a possible cladoxylopsid tree Archaeosigillaria or related lycopod

Archaeosigillaria or related lycopod

References

- Gass, Kenneth C.; Kluessendorf, Joanne; Mikulic, Donald G.; Brett, Carlton E. (2019). Fossils of the Milwaukee Formation: A Diverse Middle Devonian Biota from Wisconsin, USA. Manchester, UK: Siri Scientific Press. ISBN 978-0-9957496-7-2.

- Alden, W. C. (1906). Milwaukee. Special Folio 140. Reston, Virginia: United States Geological Survey.

- Thwaites, R.G. (1900). Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France. Vol. LX, Lower Canada, Illinois, Iroquois, Ottawas: 1675-1677. Cleveland.

- Raasch, Gilbert O. (1935). "Devonian of Wisconsin". Kansas Geological Society Guidebook for the Annual Field Conference. 9: 261–267.

- Kluessendorf, Joanne; Mikulic, Donald G.; Carman, M. R. (1988). "Distribution and depositional environments of the westernmost Devonian rocks in the Michigan Basin". Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists Memoir. 14 (1): 251–263.

- Cleland, Herdman F. (1911). The Fossils and Stratigraphy of the Middle Devonic of Wisconsin. Madison: Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey.

- Griesemer, A. D. (1965). "Middle Devonian brachiopods of Southeastern Wisconsin". Ohio Journal of Science. 65 (5): 241–295.

- Pohl, E. R. (1929). "The Devonian of Wisconsin Part 1, Lamellibranchiata". Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee. 11: 1–100.