Operation Winter '94

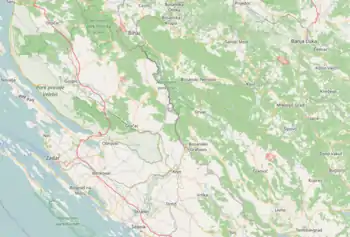

Operation Winter '94 (Serbo-Croatian: Operacija Zima '94, Операција Зима '94) was a joint military offensive of the Croatian Army (HV) and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) fought in southwestern Bosnia and Herzegovina between 29 November and 24 December 1994. The operation formed part of the Croatian War of Independence and the Bosnian War fought between Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and two unrecognized para-states proclaimed by Croatian Serbs and Bosnian Serbs. Both para-states were supported by the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and Serbia. The JNA pulled out in 1992, but transferred much of its equipment to the Bosnian Serb and Croatian Serb forces as it withdrew.

| Operation Winter '94 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence and the Bosnian War | |||||||

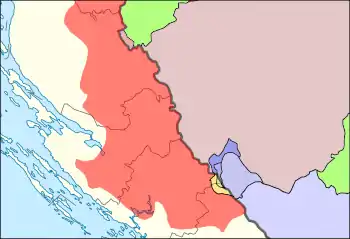

Croatia: HV-controlled, HV gains in Leap 1 & 2, ARSK-controlled Bosnia and Herzegovina: HV- or HVO-controlled since before 29 Nov 1994, Winter '94, Leap 1, Leap 2 VRS-controlled, ARBiH-controlled | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

3,000–4,000 (HV) 2,000–3,000 (HVO) | 3,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

29 killed 58 wounded 3 missing | unknown | ||||||

Operation Winter '94 was the first in a series of successful advances made by the HV and the HVO in or near the Livanjsko field, an elongated flat-bottomed valley surrounded by hills. The region was formally controlled by the HVO, but the HV contributed a substantial force, including commanding officers. The attacks were primarily designed to draw the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) away from the besieged city of Bihać. The secondary objective was threatening the single direct supply route between Drvar in the Bosnian Serb Republika Srpska and Knin, the capital of the Croatian Serb Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK).

Operation Winter '94 pushed back the front line of the VRS by about 20 kilometres (12 miles), capturing much of the Livanjsko field. The attack failed to achieve its primary objective but it brought the Croatian forces within striking distance of the Drvar–Knin road. Operation Winter '94 was followed by Operation Leap 1 (Operacija Skok 1) on 7 April 1995, which improved HV positions on Mount Dinara on the southern rim of the field, dominating the area around the RSK capital. The Croatian forces renewed their advance with Operation Leap 2 between 4 and 10 June, allowing them to directly threaten Bosansko Grahovo on the Drvar–Knin road, and to secure the remainder of the valley. The improved Croatian dispositions around Livanjsko field provided a springboard for further offensive action on this front during Operation Summer '95.

Background

Areas in Croatia controlled by:

ARSK, HV

Areas in Bosnia and Herzegovina controlled by:

VRS, ARSK, ARBiH, APWB

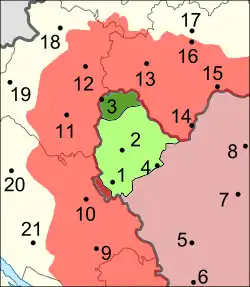

1 – Bihać, 2 – Cazin, 3 – Velika Kladuša, 4 – Bosanska Krupa, 5 – Bosanski Petrovac, 6 – Drvar, 7 – Sanski Most, 8 – Prijedor, 9 – Udbina, 10 – Korenica, 11 – Slunj, 12 – Vojnić, 13 – Glina, 14 – Dvor, 15 – Kostajnica, 16 – Petrinja, 17 – Sisak, 18 – Karlovac, 19 – Ogulin, 20 – Otočac, 21 – Gospić

Following the 1990 electoral defeat of the government of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, ethnic tensions grew. The Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija – JNA) confiscated Croatia's Territorial Defence (Teritorijalna obrana) weapons to minimize resistance.[1] On 17 August, the tensions escalated into an open revolt by Croatian Serbs,[2] centred on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around Knin,[3] parts of the Lika, Kordun, Banovina and eastern Croatia.[4] This was followed by two unsuccessful attempts by Serbia, supported by Montenegro and Serbia's provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo to obtain the Yugoslav Presidency's approval of a JNA operation to disarm Croatian security forces in January 1991.[5] After a bloodless skirmish between Serb insurgents and Croatian special police in March,[6] the JNA, supported by Serbia and its allies, asked the federal Presidency declare a state of emergency and grant the JNA wartime powers. The request was denied on 15 March, and the JNA came under control of Serbian President Slobodan Milošević. Milošević, preferring a campaign to expand Serbia rather than preservation of Yugoslavia, publicly threatened to replace the JNA with a Serbian army and declared that he no longer recognized the authority of the federal Presidency.[7] By the end of March, the conflict had escalated into the Croatian War of Independence.[8] The JNA stepped in, increasingly supporting the Croatian Serb insurgents and preventing Croatian police from intervening.[7] In early April, the leaders of the Croatian Serb revolt declared their intention to integrate the area under their control with Serbia. The Government of Croatia viewed this declaration as an attempt to secede.[9]

In May, the Croatian government responded by forming the Croatian National Guard (Zbor narodne garde – ZNG),[10] but its development was hampered by a United Nations (UN) arms embargo introduced in September.[11] On 8 October, Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia,[12] and a month later the ZNG was renamed the Croatian Army (Hrvatska vojska - HV).[10] Late 1991 saw the fiercest fighting of the Croatian War of Independence, culminating in the Siege of Dubrovnik[13] and the Battle of Vukovar.[14] A campaign of ethnic cleansing then began in the RSK, and most non-Serbs were expelled.[15][16] In January 1992, an agreement to implement the peace plan negotiated by UN special envoy Cyrus Vance was signed by Croatia, the JNA and the UN.[17] As a result, the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) deployed to maintain the ceasefire,[18] and the JNA was scheduled to retreat to Bosnia and Herzegovina, where further conflict was anticipated.[17] Despite the peace arrangement requiring an immediate withdrawal of JNA personnel and equipment from Croatia, it remained on Croatian territory for seven to eight months. When its troops eventually withdrew, the JNA left its equipment to the Army of the Republic of Serb Krajina (ARSK).[19] The January ceasefire also allowed the JNA to maintain its positions in East and West Slavonia that were on the brink of military collapse following a Croatian counteroffensive, which reclaimed 60% of the JNA-held territory in West Slavonia by the time the ceasefire went into effect.[20] However, Serbia continued to support the RSK.[21] The HV restored small areas around Dubrovnik to Croatian control[22] and during Operation Maslenica it recaptured some areas of Lika and northern Dalmatia.[23] Croatian population centres continued to be intermittently targeted by artillery, missiles and air raids throughout the war.[4][24][25][26][27]

On 9 January 1992, a Bosnian Serb state was declared, ahead of the 29 February – 1 March referendum on the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina—later cited as a pretext for the Bosnian War).[28] The Bosnian Serb state was later renamed Republika Srpska.[29] As the JNA withdrew from Croatia it started to transform into a Bosnian Serb army,[28] handing over its weapons, equipment and 55,000 troops. The process was completed in May, when the Bosnian Serb army became the Army of Republika Srpska (Vojska Republike Srpske – VRS).[30] It was faced by the Croatian Defence Council (HVO), established in April,[31] and the Bosnia and Herzegovina TO—renamed the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Armija Republike Bosne i Hercegovine – ARBiH) in May.[30] Formal establishment of these forces was preceded by the first armed clashes in the country as the Bosnian Serbs set up barricades in Sarajevo and elsewhere on 1 March and the situation rapidly escalated. Bosnian Serb artillery began shelling Bosanski Brod by the end of March,[32] and Sarajevo was first shelled on 4 April.[29] By the end of 1992, the VRS held 70% of Bosnia and Herzegovina,[33] following a large-scale campaign of conquest and ethnic cleansing backed by military and financial support from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[34] The Bosnian War gradually evolved into a three-sided conflict. The initial ARBiH–HVO alliance soon deteriorated as the forces became rivals for control of parts of the country. Ethnic tensions escalated from apparently insignificant harassment in July,[30] to an open Croat–Bosniak War by October 1992.[33] The Bosnian Croat authorities, organized in the Herzeg-Bosnia territory, were intent on attaching the region to Croatia.[34] This was incompatible with Bosniak aspirations for a unitary state.[35]

Prelude

In November 1994, the Siege of Bihać entered a critical stage as the VRS and the ARSK came close to capturing the town from the Bosniak-dominated ARBiH. Bihać was seen as a strategic area by the international community. It was thought that its capture by Serb forces would intensify the war, widening the division between the United States on one side and France and the United Kingdom on the other (advocating different approaches to the area's preservation),[36] and feared that Bihać would become the worst humanitarian disaster of the war.[37] Furthermore, denying Bihać to the Serbs was strategically important to Croatia.[38] Brigadier General Krešimir Ćosić expected the VRS and the ARSK would threaten Karlovac and Sisak once they captured Bihać, while Chief of Croatia's General Staff General Janko Bobetko believed the fall of Bihać would represent an end to Croatia's war effort.[39]

Following a US military strategy endorsed by President Bill Clinton in February 1993,[40] the Washington Agreement was signed in March 1994. This ended the Croat–Bosniak War,[39] abolished Herzeg-Bosnia,[41] established the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and forged the ARBiH–HVO alliance against the VRS.[42] In addition, a series of meetings between US and Croatian officials were held in Zagreb and Washington, D.C.[39] In November 1994, the United States unilaterally ended the arms embargo against Bosnia and Herzegovina[43]—in effect allowing the HV to supply itself as arms shipments flowed through Croatia.[42] In a meeting held on 29 November 1994, Croatian representatives proposed to attack Serb-held territory from Livno in Bosnia and Herzegovina to draw off part of the force besieging Bihać and prevent its capture by the Serbs. U.S. officials made no response to the proposal. Operation Winter '94 was ordered the same day; it was to be carried out by the HV and the HVO—the main military forces of the Bosnian Croats.[39]

Operation Winter '94 became feasible after the HVO captured Kupres (north of the Livanjsko field) in Operation Cincar on 3 November 1994, securing the right flank of the planned advance northwest of Livno. The HVO and the ARBiH advanced towards Kupres, in the first military effort coordinated between them since the Washington Agreement.[44][45]

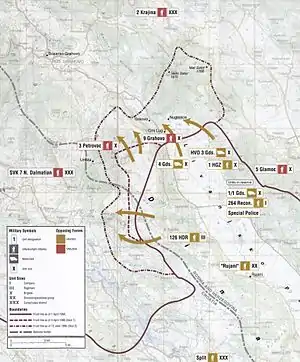

Order of battle

The HV deployed up to 9,000 troops on rotation through the area during the Operation Winter '94, keeping approximately 3,000–4,000 troops on the ground at any time,[46] and the HVO fielded an additional 2,000–3,000. The defending force of the VRS 2nd Krajina Corps consisted of about 3,500 soldiers, spread along the 55-kilometre (34 mi) front line.[47] The Bosnian Serb defenders were commanded by Colonel Radivoje Tomanić.[48] The attacking force was nominally controlled by the HVO, with Major General Tihomir Blaškić in overall command of the attack.[47] The HV General Staff appointed Major General Ante Gotovina as commander of the Split Corps and commanding officer of the HV units.[49] The Croatian forces were organized into operational groups (OG). OG Sinj was located on the left flank (on Croatian soil),[50] OG Livno in the centre and OG Kupres on the right flank of the attack in Bosnia and Herzegovina. OG Kupres mainly consisted of HVO units, while the bulk of the OG Sinj and OG Livno was made up of HV troops.[47]

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Split Corps | 1st Croatian Guards Brigade | 1. hrvatski gardijski zdrug - HGZ |

| 4th Guards Brigade | elements only | |

| 5th Guards Brigade | elements only | |

| 7th Guards Brigade | elements only | |

| 114th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 6th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 126th Home Guard Regiment |

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Tomislavgrad Corps | 1st Guards Brigade | Initially in Kupres area |

| 22nd Sabotage Detachment | ||

| 80th Home Guards Regiment | ||

| Special police | Unit of the Ministry of Interior of Herzeg-Bosnia |

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd Krajina Corps | 5th Light Infantry Brigade | In Glamoč area |

| 9th Light Infantry Brigade | In Bosansko Grahovo area | |

| 1 independent infantry company | Army of the Republic of Serb Krajina unit |

Timeline and results

Operation Winter '94 began on 29 November 1994 in heavy snow and temperatures of −20 degrees Celsius (−4 degrees Fahrenheit). One hundred and thirty soldiers from the HV 126th Home Guard Regiment commanded by Brigadier Ante Kotromanović infiltrated behind VRS positions on the left flank of the front line[50] (head of the initial north-west advance along the Livanjsko field and Mount Dinara, with most of the HV troops commanded by Gotovina[52] against the VRS 9th Light Infantry Brigade. By 3 December, the advance gained 4 to 5 kilometres (2.5 to 3.1 miles) around Donji Rujani, followed by a brief stabilization of the newly established line of contact.[53]

The advance was resumed on 6 December as the HV 4th Guards Brigade and the 126th Home Guard Regiment gradually pushing back the VRS 9th Light Infantry Brigade towards Bosansko Grahovo.[53] In more than a week of gradual advance, the force penetrated the VRS defences by 10 to 12 kilometres (6.2 to 7.5 miles) in the general direction of Bosansko Grahovo. The HVO units on the right flank of the attack made little progress towards Glamoč, and were faced with a determined VRS defence.[52] By 11 December, the VRS 9th Light Infantry Brigade had sustained losses sufficient to demoralize the unit, further complicating the battlefield situation for the VRS as the civilian population began to leave Glamoč. The civilian evacuation was nearly complete by 16 December; on that day valuables were removed from churches and monasteries in the VRS-held territory near the front line, although there was no immediate threat to them. On 23 December, the Croatian forces reached Crni Lug at the northwest rim of the Livanjsko field, forcing the VRS 9th Light Infantry Brigade to withdraw to more defensible positions.[53] On 24 December, the VRS withdrawal was complete and the operation ended.[54] In response to the reversals they had suffered, the VRS brought two brigades and two battalions from the 1st Krajina Corps, the Herzegovina Corps and the East Bosnian Corps to secure its defences in the Glamoč and Bosansko Grahovo areas and encourage civilians to return.[55]

After nearly a month of fighting, the Croatian forces had advanced by about 20 kilometres (12 miles) and had captured approximately 200 square kilometres (77 square miles) of territory northwest of Livno.[54] The VRS had been pushed back to a line approximately 19 kilometres (12 miles) south-east of Bosansko Grahovo.[56] The HV and the HVO sustained losses of 29 killed, 19 seriously wounded and 39 slightly injured troops. Three soldiers were captured by the VRS, but they were later released in a prisoner-of-war exchange.[50] In a report following Operation Winter '94, the VRS 2nd Krajina Corps reported serious manpower shortages and 20% casualties.[57] After the operation, ARSK deployed to Glamoč and Bosansko Grahovo area to assist the VRS in continued skirmishes against the Croatian forces in the area. Croatian troops retained most of the ground, representing a salient to the north-west of Livno, gained during the winter offensive.[58] The lull in fighting continued until mid-March 1995.[59]

Follow-up operations

Operation Leap 1

| Operation Leap 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence and the Bosnian War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

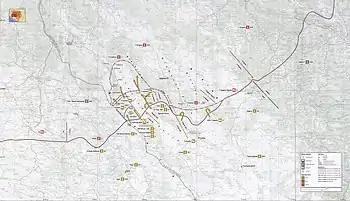

Operation Leap 1 (also known as Operation Jump 1)[60] (Operacija Skok 1) was designed to widen the salient and allow the Croatian forces to advance towards Bosansko Grahovo.[61] By spring 1995, relatively small shifts of the line of control west of the Livanjsko field enabled the VRS and the ARSK to threaten the HV positions on Dinara and Staretina mountains.[62] Gotovina was concerned that the salient established by the HV and the HVO in Operation Winter '94 was too small and was vulnerable to counterattacks by the VRS and the ARSK.[61] To create the necessary preconditions for the upcoming push, elements of the HV 4th Guards Brigade and the 126th Home Guard Regiment advanced approximately 4 kilometres (2.5 miles) over Dinara. The 4th Guards Brigade captured the strategic 1,831-metre (6,007 ft) Presedla and 1,777-metre (5,830 ft) Jankovo Brdo peaks on 14–18 March; the 126th Home Guards Regiment protected its flank, advancing through areas around the Croatia–Bosnia and Herzegovina border that were previously controlled by the ARSK.[59]

Gotovina defined several objectives for Operation Leap 1: the capture of more favourable positions, allowing the approach to ARSK-held positions around Kijevo—where a strategic mountain pass is located, and Cetina west of Dinara—where ARSK artillery positions were located; securing the left flank of the force on Dinara; preventing ARSK attacks from that direction, and regaining positions lost during the winter of 1994–1995. The operation was scheduled to allow a HV advance in two steps of 4 kilometres (2.5 miles) each, over a period of one to two days.[59]

Operation Leap 1 took place on 7 April 1995. The HV 7th Guards Brigade relieved the 4th Guards Brigade and advanced for about 5 kilometres (3.1 miles), pushing the VRS defences along a 15-kilometre (9.3-mile)-wide front line and capturing approximately 75 square kilometres (29 square miles) of territory.[59] This one-day operation moved the front line—from which the VRS 9th Light Infantry Brigade had intermittently mounted attacks during the previous three months—north-west,[63] and put the HV within easy reach of Uništa—one of the few passes over Dinara.[62] A secondary objective of the operation was also achieved; the salient created during Operation Winter '94 was extended towards Bosansko Grahovo and stabilized. The 126th Home Guard Regiment protected the left flank of the 7th Guards Brigade axis of advance, engaging in several skirmishes.[59]

Operation Leap 2

| Operation Leap 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence and the Bosnian War | |||||||

Map of Operations Leap 1 and Leap 2 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000 | 3,500 | ||||||

Operation Leap 2, or Operation Jump 2[60] (Operacija Skok 2) was a joint operation of the HV and the HVO aimed primarily at capturing the main mountain pass out of the Livanjsko field on the Livno-Bosansko Grahovo road, and the high ground overlooking Glamoč, to give the Croatian forces good positions from which to advance further into VRS-held territory. It was thought that the attack might also force the VRS to withdraw some of its forces that had been attacking the Orašje pocket since May. Gotovina planned a two-stage, two-pronged advance towards the main objectives and an auxiliary attack on ARSK-held territory south-west of the salient. In the first stage of the operation, the attacking forces were tasked with capturing the village of Crni Lug and the southern part of the pass,[64] while the second stage was planned to capture the 1,872-metre (6,142 ft) Mount Šator and the Crvena Zemlja ridge to the north,[65] blocking the Bosansko Grahovo-Glamoč road and making Glamoč difficult to resupply.[64]

The Croatian forces fielded approximately 5,000 troops, spearheaded by the HV 4th Guards Brigade[64] and supported by the 1st Croatian Guards Brigade (1. hrvatski gardijski zdrug - HGZ), the 1st Battalion of the 1st Guards Brigade, the 3rd Battalion of the 126th Home Guard Regiment of the HV, the HVO 3rd Guards Brigade and the Bosnian Croat special police.[65][66] The opposing forces comprised approximately 3,000 troops in three light infantry brigades of the VRS 2nd Krajina Corps and a 500-strong ARSK composite Vijuga battlegroup, assembled by the ARSK 7th North Dalmatian Corps.[67] The Vijuga battlegroup was deployed with elements of the ARSK 1st Light Infantry Brigade in the Croatia-Bosnia and Herzegovina border zone on Dinara. The VRS formations consisted of the 3rd and the 9th Light Infantry Brigades in the Bosansko Grahovo area and the 5th Light Infantry Brigade in the Glamoč zone. The reinforcements that had been sent to the area in the aftermath of Operation Winter '94 were broken up and used to reinforce the VRS brigades.[68]

Operation Leap 2 began on 4 June with the advance of the HV 4th Guards Brigade. HVO troops took Crni Lug and the mountain pass en route to Bosansko Grahovo, the operation's chief objective.[67] Its left flank, in the border area, was protected by the 3rd Battalion of the 126th Home Guard Regiment and the Tactical Sniper Company attached to the HV Split Corps.[66] The VRS counterattacked on 6–7 June, trying to roll back the 4th Guards Brigade. The VRS push failed, as did its efforts to contain the advance with close air support and M-87 Orkan rockets. On 6 June (the same day as the VRS counterattack), the second phase of Operation Leap 2 began. The 1st Battalion of the 1st Guards Brigade supported by the HV 264th Reconnaissance Sabotage Company and elements of the HV 1st HGZ advanced north from Livno, capturing the high ground near Glamoč and blocking the Bosansko Grahovo-Glamoč road by 10 June.[67] To pin down the VRS on the right flank of the attack, the HVO 2nd Guards Brigade attacked VRS positions on Golija Mountain south-west of Glamoč.[66]

Operations Leap 1 and 2 improved the positions of the Croatian forces east and west of the Livanjsko field, and brought Bosansko Grahovo and Glamoč within striking distance. The advance secured the valley, threatened Glamoč and brought the Bosansko Grahovo-Glamoč road, the Cetina valley and the Vrlika field within Croatian artillery range.[69] The Croatian forces sustained losses of 4 killed, 15 seriously wounded and 19 slightly injured during Operations Leap 1 and 2.[70]

Aftermath

Gotovina said that although Operations Winter '94, Leap 1 and Leap 2 were planned and executed as three distinct operations, they represent a unified military action.[67] Operation Winter '94 ostensibly failed to achieve its primary objective of relieving pressure on the Bihać pocket by drawing off VRS and ARSK forces to contain the attack; however, that was due to a decision by Chief of VRS General Staff General Ratko Mladić and not to mistakes in planning or execution. Faced with a choice between continuing with the attack on Bihać and blocking the advance from the Livanjsko field, the VRS chose not to move its forces, but Bihać was successfully defended by the 5th Corps of the ARBiH.[54] The secondary objective of Operation Winter '94 was achieved more easily; the Croatian forces approached the Knin-Drvar road and directly threatened the main supply route between the Republika Srpska and the RSK capital.[54] Operations Leap 1 and 2 built on the achievements of Operation Winter '94, threatened Bosansko Grahovo and created conditions to isolate Knin in Operation Summer '95, which was executed the following month.[67][71] The advance was strategically significant;[72] Mladić's decision not to react to Operation Winter '94 was a gamble which ultimately cost the Republika Srpska territory extending to Jajce, Mrkonjić Grad and Drvar and brought about the destruction of the RSK as the advances of the Croatian forces paved the way for Operation Storm.[73]

Footnotes

- Hoare 2010, p. 117

- Hoare 2010, p. 118

- The New York Times & 19 August 1990

- ICTY & 12 June 2007

- Hoare 2010, pp. 118–119

- Ramet 2006, pp. 384–385

- Hoare 2010, p. 119

- The New York Times & 3 March 1991

- The New York Times & 2 April 1991

- EECIS 1999, pp. 272–278

- The Independent & 10 October 1992

- Narodne novine & 8 October 1991

- Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, pp. 249–250

- The New York Times & 18 November 1991

- Department of State & 31 January 1994

- ECOSOC & 17 November 1993, Section J, points 147 & 150

- The New York Times & 3 January 1992

- Los Angeles Times & 29 January 1992

- Armatta 2010, p. 197

- Hoare 2010, p. 123

- Thompson 2012, p. 417

- The New York Times & 15 July 1992

- The New York Times & 24 January 1993

- ECOSOC & 17 November 1993, Section K, point 161

- The New York Times & 13 September 1993

- The Seattle Times & 16 July 1992

- The New York Times & 17 August 1995

- Ramet 2006, p. 382

- Ramet 2006, p. 428

- Ramet 2006, p. 429

- Eriksson & Kostić 2013, pp. 26–27

- Ramet 2006, p. 427

- Ramet 2006, p. 433

- Bieber 2010, p. 313

- Burg & Shoup 2000, p. 68

- The Independent & 27 November 1994

- Halberstam 2003, pp. 284–286

- Hodge 2006, p. 104

- Jutarnji list & 9 December 2007

- Woodward 2010, p. 432

- Jutarnji list & 16 September 2006

- Ramet 2006, p. 439

- Bono 2003, p. 107

- CIA 2002, pp. 242–243

- CIA 2002, note 227/V

- CIA 2002, note 304/V

- CIA 2002, p. 250

- SVK & 6 December 1994

- Nova TV & 16 November 2012

- Slobodna Dalmacija & 30 November 2011

- Sinjske novine & November 2011

- CIA 2002, pp. 250–251

- RSK & 23 December 1994

- CIA 2002, p. 251

- Marijan 2007, p. 47

- Marijan 2007, p. 46

- Marijan 2007, p. 241

- CIA 2002, p. 295

- CIA 2002, p. 296

- MORH 2011, p. 17

- CIA 2002, pp. 295–296

- Marijan 2007, pp. 47–48

- Marijan 2007, note 77

- CIA 2002, p. 299

- Marijan 2007, pp. 48–49

- CIA 2002, note 94

- CIA 2002, p. 300

- CIA 2002, note 95

- Hrvatski vojnik & July 2010

- Slobodna Dalmacija & 12 July 2007

- CIA 2002, pp. 364–366

- Ripley 1999, p. 86

- Sekulić 2000, p. 96

References

- Books

- Armatta, Judith (2010). Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4746-0.

- Bieber, Florian (2010). "Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1990". In Ramet, Sabrina P (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 311–327. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Burg, Steven L.; Shoup, Paul S. (2000). The War in Bosnia Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3189-3.

- Bjelajac, Mile; Žunec, Ozren (2009). "The War in Croatia, 1991–1995". In Charles W. Ingrao; Thomas Allan Emmert (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. pp. 230–271. ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7.

- Bono, Giovanna (2003). Nato's 'Peace Enforcement' Tasks and 'Policy Communities': 1990–1999. Farnham, England: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-0944-5.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. OCLC 50396958.

- Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. London, England: Routledge. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Eriksson, Mikael; Kostić, Roland (2013). Mediation and Liberal Peacebuilding: Peace from the Ashes of War?. London, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-18916-6.

- Halberstam, David (2003). War in a Time of Peace: Bush, Clinton and the Generals. London, England: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-6301-3.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–136. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Hodge, Carole (2006). Britain And the Balkans: 1991 Until the Present. London, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-29889-6.

- Marijan, Davor (2007). Oluja [Storm] (PDF) (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian memorial-documentation center of the Homeland War of the Government of Croatia. ISBN 978-953-7439-08-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918–2006. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Ripley, Tim (1999). Operation Deliberate Force: The UN and NATO Campaign in Bosnia 1995. Lancaster, England: Centre for Defence and International Security Studies. ISBN 978-0-9536650-0-6.

- Sekulić, Milisav (2000). Knin je pao u Beogradu [Knin was lost in Belgrade] (in Serbian). Bad Vilbel, Germany: Nidda Verlag. OCLC 47749339.

- Thompson, Wayne C. (2012). Nordic, Central & Southeastern Europe 2012. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-61048-891-4.

- Woodward, Susan L. (2010). "The Security Council and the Wars in the Former Yugoslavia". In Vaughan Lowe; Adam Roberts; Jennifer Welsh; et al. (eds.). The United Nations Security Council and War:The Evolution of Thought and Practice Since 1945. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 406–441. ISBN 978-0-19-161493-4.

- News reports

- Bellamy, Christopher (10 October 1992). "Croatia built 'web of contacts' to evade weapons embargo". The Independent. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012.

- Bonner, Raymond (17 August 1995). "Dubrovnik Finds Hint of Deja Vu in Serbian Artillery". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013.

- Daly, Emma; Marshall, Andrew (27 November 1994). "Bihac fears massacre". The Independent. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012.

- Engelberg, Stephen (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013.

- "Godine borbe za slobodu: Ratni put Ante Gotovine" [Years of struggle for freedom: Wartime history of Ante Gotovina] (in Croatian). Nova TV (Croatia). 16 November 2012. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013.

- Juras, Žana (12 July 2007). "Zagorec ima više odličja nego čitava kninska bojna" [Zagorec has more medals than the entire Knin Battalion]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 30 November 2013.

- Kaufman, Michael T. (15 July 1992). "The Walls and the Will of Dubrovnik". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013.

- Maass, Peter (16 July 1992). "Serb Artillery Hits Refugees – At Least 8 Die As Shells Hit Packed Stadium". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013.

- Paštar, Toni (30 November 2011). "Na vrhu Malog Maglaja obilježena 17. obljetnica akcije Zima '94" [The 17th anniversary of Operation Winter '94 marked at the Mali Maglaj peak]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Pavić, Snježana (16 September 2006). "Tuđman nije shvaćao da će riječ Amerike biti zadnja" [Tuđman did not understand that the American decision will be final]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 30 November 2013.

- Ratković, Filip (November 2011). "Obilježena 17. godišnjica vojne akcije "Zima '94."" [The 17th anniversary of military Operation Winter '94 marked] (PDF). Sinjske novine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 November 2013.

- "Rebel Serbs List 50 Croatia Sites They May Raid". The New York Times. 13 September 1993. Archived from the original on 29 December 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". The New York Times. Reuters. 19 August 1990. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (24 January 1993). "Croats Battle Serbs for a Key Bridge Near the Adriatic". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (18 November 1991). "Croats Concede Danube Town's Loss". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (3 January 1992). "Yugoslav Factions Agree to U.N. Plan to Halt Civil War". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013.

- Vurušić, Vlado (9 December 2007). "Krešimir Ćosić: Amerikanci nam nisu dali da branimo Bihać" [Krešimir Ćosić: Americans did not let us defend Bihać]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Williams, Carol J. (29 January 1992). "Roadblock Stalls U.N.'s Yugoslavia Deployment". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012.

- International, governmental, and NGO sources

- "Croatia human rights practices, 1993; Section 2, part d". United States Department of State. 31 January 1994. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013.

- "Odluka" [Decision]. Narodne novine (in Croatian). Narodne novine d.d. (53). 8 October 1991. ISSN 1333-9273.

- "Oluja – bitka svih bitaka" [Storm – battle of all battles]. Hrvatski vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia). July 2010. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Marijan, Davor, ed. (23 December 1994). "Ratni dnevnik GŠ SVK od 30. 10 do" [Battlefield log HQ of the ARSK from 30 October till]. Oluja [Storm] (PDF) (in Serbian). Croatian memorial-documentation center of the Homeland War of the Government of Croatia. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-953-7439-08-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Pintarić, Vesna; Parlov, Leida; Vlašić, Toma. "20 years of the Croatian armed forces" (PDF). Ministry of Defence (Croatia). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Situation of human rights in the territory of the former Yugoslavia". United Nations Economic and Social Council. 17 November 1993. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic – Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007.

- Tomanić, Radivoje (6 December 1994). "Redovni borbeni izvještaj – Str. pov. br. 2/1-348" [Regular battle report – Top secret nr. 2/1-348]. In Marijan, Davor (ed.). Oluja [Storm] (PDF) (in Serbian). Croatian memorial-documentation center of the Homeland War of the Government of Croatia. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-953-7439-08-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2013.