Pelusios

Pelusios is a genus of African side-necked turtles. With 17 described species, it is one of the most diverse genera of the turtle order (Testudines).

| Pelusios | |

|---|---|

| |

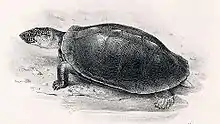

| Pelusios castaneus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Pleurodira |

| Family: | Pelomedusidae |

| Genus: | Pelusios Wagler, 1830[1][2] |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

|

Sternothaerus Bell, 1825 | |

Etymology

The Latin name Pelusios means "mud" or "clay", and this is reflected by the turtles habitually burying themselves to find refuge and food.

Common names

Common names for the genus Pelusios include hinged terrapins,[3] African mud turtles, and mud terrapins.

Taxonomy

Several species have been described, with probably numerous undescribed species. The taxonomy of the genus is very confused, as these species show many local variations. Certain species, in isolated areas or with reduced populations, need to be observed as they face a distinct extinction possibility given the significant number collected by native people.

Geographic range

They are found throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, Madagascar, São Tomé, and the Seychelles islands. They have also been introduced on the islands of the Lesser Antilles.

Description

The African mud turtles range from being small in size, only 12 cm (4.7 in) carapace length for adult Pelusios nanus, to moderately large, 46 cm (18 in) for adult Pelusios sinuatus, while the large majority of species fall between 20 and 30 cm (7.9 and 11.8 in) carapace length.[4] The carapaces are oblong, moderately high-domed, and the plastrons are large and hinged which is what distinguishes them from the Pelomedusa.[4][5] The plastron contains a mesoplastron and also well-developed plastral buttresses that articulate with the costals on each side of the carapace.[4] The carapace has 11 pairs of sutured peripherals around its margin and a neck without costiform processes.[4] The jaw closure articulates on a pterygoid trochlear surface which lacks a synovial capsule but instead contains a saclike duct full of fluid from the mouth cavity.[4] The head shape is wide and flat, with a seemingly "smiling" face created by the jaw closure.[5] The skull lacks the epipterygoid bone (bone above the pterygoid extending to parietal bone) and parietal-squamosal contact but possesses an internal carotid canal and strong postorbital-squamosal contact.[4]

Biology

The mud terrapins are either semiaquatic or fully aquatic and typically walk on the floor of slow-moving waters. They are most often observed in lakes, swamps or marshes but occasionally witnessed in ephemeral waterways.[4] They are predominantly carnivorous, eating a variety of arthropods, worms, or other small animals found by way of foraging the bottom of their aquatic habitats.[4] They do not undergo prolonged estivation or hibernation in the dried mud during dry season; instead, they need to find a wet or humid place to survive.[5] Pelusios generally produce small to modest clutches of 6 to 18 eggs, depending upon female size.[4][6] Egg deposition occurs in the more equitable season of the year, with known incubation periods ranging from 8–10 weeks.[4] The reported karyotype is 2N = 34 with 22 macrochromosomes and 12 microchromosomes.[7] The southern group of the genus Pelomedusa is shown to be paraphyletically similar to Pelusios through mitochondrial DNA analyses.[2][8] From fossil evidence, it is suggested that the genera diverged in, or before the lower Miocene era.[8]

List of species

The species in the genus Pelusios can be divided into two groups based on shell morphology. The "adansonii group" (also known as the "gabonensis group" or the "adansonii-gabonensis group") includes P. adansonii, P. broadleyi, P. gabonensis, P. marani, and P. nanus. Species in the "adansonii group" are characterized by short abdominal scutes relative to the elongate anterior plastral lobe, as well as a short bridge between the carapace and the plastron.[2] All of the remaining species are characterized by relatively longer abdominal scutes and a longer bridge between the carapace and plastron and are referred to as the "subniger group".[2][7] Species in the "subniger group" exhibit greater mobility of the plastral front lobe than those belonging to the "adansonii group".

Status

Based on field surveys, a 50% decrease has been observed in the Seychelles terrapins, which include various Pelusios species.[12] Seychelles is considered a hotspot for biodiversity, as it is one of the most threatened reservoirs of plant life and animal life, as well as one of the richest environments.[13] The species are endangered due to threat of drainage, predation, and invasion by alien flora, combined with a shrunken living area.[12][13] Most habitat destruction is from human population expansion, specifically in the granitic islands due to increased development pressures.[13] Hope for reversal of this trend is evidenced by the rapid population recovery of Pelusios subniger parietalis on Frégate Island after habitat improvement.[12] Global climate change has recently been recognized as one of the largest threats to biodiversity.[14] This climate change has the ability to change species survival by causing changes in ecosystem structures,[13] yet the effect is heightened in endemic species.[14] Several reviews undertaken for the study of potential effects of global warming on biodiversity have provided evidence for Africa being the most vulnerable of all continents.[15] Climate change is likely to be devastating for many species confined to small islands such as Seychelles.[13] Endemic species such as Pelusios could suffer the worst impact of climate change because of their restricted range and narrow ecological requirements.

Notes

- A binomial authority in parentheses indicates the species was originally described in a genus other than Pelusios.

References

- Rhodin 2011, p. 000.215

- Fritz 2007, pp. 345-346

- Branch, Bill. 2004. Field Guide to Snakes and Other Reptiles of Southern Africa. Sanibel Island, Florida: Ralph Curtis Books. 399 pp. ISBN 0-88359-042-5. (Genus Pelusios, p. 46).

- Vitt, Laurie; Calwell, Janalee (2008). Herpetology. Wiltham, Massachusetts: Academic. ISBN 978-0-12-374346-6.

- Bonin, Franck; Devaux, Bernard; Dupre, Alain (2006). Turtles of the World (Third ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8496-9.

- Franklin, C (2007). Turtles: An extraordinary natural history 245 million years in the making. St. Paul, Minnesota: Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-2981-8.

- Ernst, C; Barbour, R. (1989). Turtles of the World. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Press. ISBN 0-87474-414-8.

- Vargas-Ramirez M, Vences M, Branch WR, Daniels SR, Glaw F, Hofmeyr MD, Kuchling G, Maran J, Papenfuss TJ, Siroký P, Vieites DR, Fritz U. (July 2010). "Deep genealogical lineages in the widely distributed African helmeted terrapin: Evidence from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56: 428–440. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.03.019. PMID 20332032.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- The Reptile Database. www.reptile-database.org.

- Turtle Taxonomy Working Group [van Dijk, P.P., Iverson, J.B., Rhodin, A.G.J., Shaffer, H.B., and Bour, R.]. 2014. "Turtles of the World, 7th edition: annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution with maps, and conservation status". In: Rhodin, A.G.J., Pritchard, P.C.H., van Dijk, P.P., Saumure, R.A., Buhlmann, K.A., Iverson, J.B., and Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.). Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. Chelonian Research Monographs 5(7):000.329–479 doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v7.2014

- Bruce G. Marcot, "Two Turtles from Western Democratic Republic of the Congo: Pelusios chapini and Kinixys erosa." Includes photos.

- Gerlach, J (August 2008). "Fragmentation and demography as causes of population decline in Seychelles freshwater turtles (genus Pelusios)". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 7: 78–87. doi:10.2744/ccb-0635.1.

- Bombi, Pierluigi; D'Amen, Manuela; Gerlach, Justin; Luiselli, Luca (2009). "Will climate change affect terrapin conservation in Seychelles". Phelsuma (17A): 1–12.

- Thomas CD, Cameron A, Green RE, Bakkenes M, Beaumont LJ, Collingham YC, Erasmus BFN, de Siqueira MF, Grainger A, Hannah L, Hughes L, Huntley B, van Jaarsveld AS, Midgley GF, Miles L, Ortega-Huerta MA, Peterson AT, Phillips OL, Williams SE. 2004. "Extinction risk from climate change". Nature 427: 145–148.

- Hulme M. 1996. Climate Change and Southern Africa: an Exploration of Some Potential Impacts and implications in the SADC. Norwich: United Kingdom: WWF International and Climate Research Unit, UEA. 104 pp.

Bibliography

- Rhodin, Anders G.J.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Iverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley; Bour, Roger. (2011-12-31). "Turtles of the World, 2011 update: Annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution and conservation status" (PDF). Chelonian Research Monographs. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-01-22.

- Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter. (2007-10-31). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (pdf). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-12-29. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- Caldwell, Analee; Vitt, Laurie. (2008). Herpetology. Waltham, Massachusetts: Academic Press. Print.

- Wagler, J. 1830. Natürliches System der AMPHIBIEN, mit vorangehender Classification der SÄUGTHIERE und VÖGEL. Ein Beitrag zur vergleichenden Zoologie. Munich, Stuttgart and Tübingen: J.G. Cotta. vi + 354 pp. + one plate. (Pelusios, new genus, p. 137). (in German and Latin).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pelusios. |

_(7080593585).jpg.webp)