Phengaris alcon

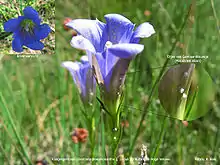

Phengaris alcon, the Alcon blue or Alcon large blue, is a butterfly of the family Lycaenidae and is found in Europe and across the Palearctic to Siberia and Mongolia.

_(8145303452).jpg.webp)

| Alcon blue | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. alcon |

| Binomial name | |

| Phengaris alcon (Denis & Schiffermüller, 1775) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description from Seitz

L. alcon Schiff. (= areas Esp., euphemus Godt.) (83 a). Large, the male above deep blue, but without brilliant gloss. The female black-brown, dusted with dark blue in the basal area. The dark violet-grey underside has numerous ocelli. L. alcon is easily distinguished from the following species (coeligena, euphemus, arcas, arion, arionides ...) by the male bearing on the blue disc of the forewing no other black spots but the discocellular lunule. Central Europe and North Asia, from the coast of the North Sea (Hamburg, Bremen, Belgium) to the Mediterranean, and from France to the Altai, Dauria and Tibet, ab. nigra Wheel, has the males strongly darkened, the females being quite black above. In ab. cecinae Hormuz. the ocelli of the underside are absent or strongly reduced. In ab. pallidior Schultz the margin is grey instead of black. — marginepunctata Gillm. has a row of black dots before the margin, almost parallel with it; found by Hafner at Loitsch and other places in Carniolia.— In the form rebeli Hirschke the blue of the upperside is more brilliant and more extended, the dark margin being reduced, in the female only the apical area black; Styria. — monticola Stgr. (83 a) has a narrow black margin like rebeli, but the blue is very deep and dark, so dull as in true alcon; from the Alps of Switzerland and the Caucasus. — Egg white, finely reticulated, laid on the flowers of the food-plant (Gentiana pneumonanthe). The larva generally does not break through the shell on the upperside, so that the holes of empty eggs are not easily noticed. At first grey, later on reddish brown with dark dorsal line and dark head. The butterflies occur on damp meadows where Gentiana grows; they are plentiful in such places, sometimes even in abundance, from the end of May into July, in the North not before the end of June.[2]

Taxonomy

There are five subspecies:

- P. a. alcon (Central Europe)

- P. a. jeniseiensis (Shjeljuzhko, 1928) (southern Siberia)

- P. a. sevastos Rebel & Zerny, 1931 (Carpathians)

- P. a. xerophila Berger, 1946 (Central Europe)

- †P. a. arenaria (Netherlands)

There has been controversy over whether Phengaris rebeli, currently regarded as an ecotype within the Alcons, should be listed as a separate species. The two types are morphologically indistinguishable and molecular analysis has revealed little genetic difference, mostly attributable to localized habitat adaptation.[3][4][5] Still some maintain that they should be treated as distinct species, especially for conservation purposes, because they parasitise different host ant colonies and parasitise these ants at different rates,[6] and also rely on different host plant species (Gentiana pneumonanthe in the case of Phengaris alcon and Gentiana cruciata in the case of Phengaris rebeli).[7]

Ecology

_depositing_an_egg.jpg.webp)

The species can be seen flying in mid- to late summer. It lays its eggs onto the marsh gentian (Gentiana pneumonanthe); in the region of the Alps they are sometimes also found on the related willow gentian (Gentiana asclepiadea).[8] The caterpillars eat no other plants.

Parasitic relationship

Like some other species of Lycaenidae, the larval (caterpillar) stage of P. alcon depends on support by certain ants; it is therefore known as a myrmecophile.

Alcon larvae leave the food plant when they have grown sufficiently (4th instar) and wait on the ground below to be discovered by ants. The larvae emit surface chemicals (allomones) that closely match those of ant larvae, causing the ants to carry the Alcon larvae into their nests and place them in their brood chambers. Once adopted into a nest, Alcon larvae are fed the regurgitations of nurse ants (just as other ant brood), a process called trophallaxis.[9] This parasitic method is known as the "cuckoo" strategy and is an alternative to the predatory strategy employed by most other members of the genus such as Phengaris arion.[10] Though less common, the cuckoo strategy has been found to have several advantages over the predatory strategy. For one, it is more trophically efficient than preying directly on other ant grubs, and as a result, significantly more cuckoo-type larvae can be supported per nest than predatory larvae.[9] Another advantage of cuckoo feeding is that individuals, having pursued a higher degree of social integration, have a higher chance of surviving when a nest is overcrowded or facing food shortage because ants preferentially feed the larvae; compared to the type of scramble competition that can devastate predatory larvae, this contest competition results in much lower mortality.[11][12] Though the cuckoo strategy has its advantages, it also comes with important costs; with greater host ant specialization comes much more limited ecological niches.[12]

When the Alcon larva is fully developed it pupates. Once the adult hatches it will leave the ant nest.

Over time, some ant colonies that are parasitized in this manner will slightly change their larva chemicals as a defence, leading to an evolutionary "arms race" between the two species.[13][14]

Generally, Lycaenidae species which have a myrmecophilous relationship with the ant genus Myrmica are locked to primary host specificity. The Alcon blue is unusual in this regard in that it uses different host species in different locations throughout Europe, and often uses multiple host species even within the same location and population.[15][16][17] Though it may be adopted into the nests of multiple Myrmica species within a given site, there is typically one "primary" species with which the locally adapted larvae can best socially integrate, leading to drastically higher survival rates.[9] Across Europe, Alcons are known to use Myrmica scabrinodis, Myrmica ruginodis, Myrmica rubra, Myrmica sabuleti, Myrmica scabrinodis, Myrmica schencki, and rarely Myrmica lonae, and Myrmica specioides.[18][19]

Predation

P. alcon larvae are sought underground by the Ichneumon eumerus wasp. On detecting a P. alcon larva the wasp enters the nest and sprays a pheromone that causes the ants to attack each other. In the resulting confusion the wasp locates the butterfly larva and injects it with its eggs. On pupation, the wasp eggs hatch and consume the chrysalis from the inside.[20]

See also

- Orachrysops niobe Brenton blue butterfly from South Africa, with a similar lifecycle

References

- Gimenez Dixon (1996). "Maculinea alcon". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996. Retrieved 8 May 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seitz, A. ed. Band 1: Abt. 1, Die Großschmetterlinge des palaearktischen Faunengebietes, Die palaearktischen Tagfalter, 1909, 379 Seiten, mit 89 kolorierten Tafeln (3470 Figuren)

- Als, Thomas D.; Vila, Roger; Kandul, Nikolai P.; Nash, David R.; Yen, Shen-Horn; Hsu, Yu-Feng; Mignault, André A.; Boomsma, Jacobus J.; Pierce, Naomi E. (2004). "The evolution of alternative parasitic life histories in large blue butterflies". Nature. 432 (7015): 386–390. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..386A. doi:10.1038/nature03020. PMID 15549104.

- Fric, Zdenĕk; Wahlberg, Niklas; Pech, Pavel; Zrzavý, Jan (1 July 2007). "Phylogeny and classification of the Phengaris–Maculinea clade (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae): total evidence and phylogenetic species concepts". Systematic Entomology. 32 (3): 558–567. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.2007.00387.x. ISSN 1365-3113.

- Ugelvig, L. V.; Vila, R.; Pierce, N. E.; Nash, D. R. (1 October 2011). "A phylogenetic revision of the Glaucopsyche section (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae), with special focus on the Phengaris–Maculinea clade". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 61 (1): 237–243. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.05.016. PMID 21669295.

- Tartally, A; Nash, D. R.; Lengyel, S.; Varga, Z (2008). "Patterns of host ant use by sympatric populations of Maculinea alcon and M.'rebeli'in the Carpathian Basin". Insectes Sociaux. 55 (4): 370–381. doi:10.1007/s00040-008-1015-4.

- Thomas, J. A.; Elmes, G. W.; Wardlaw, J. C.; Woyciechowski, M. (1989). "Host specificity among Maculinea butterflies in Myrmica ant nests". Oecologia. 79 (4): 452–457. Bibcode:1989Oecol..79..452T. doi:10.1007/BF00378660. ISSN 0029-8549. PMID 28313477.

- Bellmann, Heiko (2003). Der neue Kosmos-Schmetterlingsführer (in German). ISBN 978-3-440-09330-6.

- Thomas, J. A.; Elmes, G. W. (1 November 1998). "Higher productivity at the cost of increased host-specificity when Maculinea butterfly larvae exploit ant colonies through trophallaxis rather than by predation". Ecological Entomology. 23 (4): 457–464. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2311.1998.00153.x. ISSN 1365-2311.

- Thomas, J.A.; J.C. Wardlaw (1990). "The effect of queen ants on the survival of Maculinea arion larvae in Myrmica ant nests". Oecologia. 85 (1): 87–91. Bibcode:1990Oecol..85...87T. doi:10.1007/bf00317347. PMID 28310959.

- Thomas, J. A.; Wardlaw, J. C. (1992). "The capacity of a Myrmica ant nest to support a predacious species of Maculinea butterfly". Oecologia. 91 (1): 101–109. Bibcode:1992Oecol..91..101T. doi:10.1007/BF00317247. ISSN 0029-8549. PMID 28313380.

- Elmes, G. W.; Thomas, J. A.; Wardlaw, J. C.; Hochberg, M. E.; Clarke, R. T.; Simcox, D. J. (1998). "The ecology of Myrmica ants in relation to the conservation of Maculinea butterflies". Journal of Insect Conservation. 2 (1): 67–78. doi:10.1023/A:1009696823965. ISSN 1366-638X.

- Nash, David R.; Als, Thomas D.; Maile, Roland; Jones, Graeme R.; Boomsma, Jacobus J. (4 January 2008). "A Mosaic of Chemical Coevolution in a Large Blue Butterfly". Science. 319 (5859): 88–90. Bibcode:2008Sci...319...88N. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.413.7297. doi:10.1126/science.1149180. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18174441.

- Cressey, Daniel (2008). "The battle of the butterflies and the ants". Nature News. 3. doi:10.1038/news.2007.405.

- Akino, T.; Knapp, J. J.; Thomas, J. A.; Elmes, G. W. (22 July 1999). "Chemical mimicry and host specificity in the butterfly Maculinea rebeli, a social parasite of Myrmica ant colonies". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 266 (1427): 1419–1426. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0796. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1690087.

- Elmes, G.; Akino, T.; Thomas, J.; Clarke, R.; Knapp, J. (2002). "Interspecific differences in cuticular hydrocarbon profiles of Myrmica ants are sufficiently consistent to explain host specificity by Maculinea (large blue) butterflies". Oecologia. 130 (4): 525–535. Bibcode:2002Oecol.130..525E. doi:10.1007/s00442-001-0857-5. ISSN 0029-8549. PMID 28547253.

- Thomas, Jeremy A.; Elmes, Graham W.; Sielezniew, Marcin; Stankiewicz-Fiedurek, Anna; Simcox, David J.; Settele, Josef; Schönrogge, Karsten (22 January 2013). "Mimetic host shifts in an endangered social parasite of ants". Proc. R. Soc. B. 280 (1751): 20122336. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.2336. eISSN 1471-2954. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3574407. PMID 23193127.

In three Ma. rebeli populations over 5 years in the Spanish Pyrenees, we found that eggs were laid indiscriminately on G. cruciata growing in the territories of four species of Myrmica

- Steiner, Florian M.; Sielezniew, Marcin; Schlick-Steiner, Birgit C.; Höttinger, Helmut; Stankiewicz, Anna; Górnicki, Adam (2003). "Host specificity revisited: New data on Myrmica host ants of the lycaenid butterfly Maculinea rebeli". Journal of Insect Conservation. 7 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1023/A:1024763305517. ISSN 1366-638X.

- Tartally, A.; Nash, D. R.; Lengyel, S.; Varga, Z. (28 June 2008). "Patterns of host ant use by sympatric populations of Maculinea alcon and M. 'rebeli' in the Carpathian Basin". Insectes Sociaux. 55 (4): 370–381. doi:10.1007/s00040-008-1015-4. ISSN 0020-1812.

- "Butterfly and Wasp: A Devious, Deceitful Cycle of Life". Wired. 4 January 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maculinea alcon. |