Prads-Haute-Bléone

Prads-Haute-Bléone (Prats Auta Blèuna in Vivaro-Alpine) is a commune in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence department and in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in southeastern France.

Prads-Haute-Bléone | |

|---|---|

A general view of the village of Prads-Haute-Bléone | |

Coat of arms | |

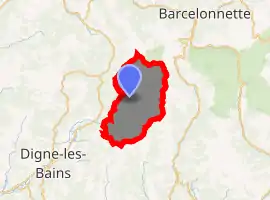

Location of Prads-Haute-Bléone

| |

Prads-Haute-Bléone  Prads-Haute-Bléone | |

| Coordinates: 44°13′15″N 6°26′38″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur |

| Department | Alpes-de-Haute-Provence |

| Arrondissement | Digne-les-Bains |

| Canton | Seyne |

| Intercommunality | Haute Bléone |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2008–2014) | Bernard Bartolini |

| Area 1 | 165.64 km2 (63.95 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-01-01)[1] | 182 |

| • Density | 1.1/km2 (2.8/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 04155 /04390 |

| Elevation | 831–2,961 m (2,726–9,715 ft) (avg. 1,036 m or 3,399 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

The people of Prads-Haute-Bléone are called Pradins.[2]

Geography

The neighboring communes of Prads-Haute-Bléone are Méolans-Revel, Allos, Villars-Colmars, Thorame-Basse, Draix, La Javie, Beaujeu and Verdaches.

The village lies on the right bank of the Bléone, which has its source in the northeastern part of the commune and flows southwest through the middle of the commune.

The municipality of Prads-Haute-Bléone extends over 16,500 hectares (41,000 acres), it is composed of nine hamlets ranging in elevation from 800 to 1 450 metres. The main settlement of Prads is at 1,048 metres (3,438 ft),[3] and the highest peak is the Tête de l'Estrop at 2,961 metres (9,715 ft) in the Massif des Trois-Évêchés at the border with Méolans-Revel. This is also the highest summit of the Provence Alps and Prealps.

It is common with the type of high valleys of the Southern Alps, enjoying a climate which is very sunny, cold, dry, and with a snow line at approximately 1,800 metres (5,900 ft).

Geology

During the two last major glaciations, Riss glaciation and Würm glaciation, major glaciers occupied the valleys of the commune. A first glacier, reduced, occupied the top of the Valley of the Galebre (formerly commune of Mariaud). A great glacier flowed into the Bléone Valley; It received tributaries from the glacier valleys of the ravine of Bussing, Riou and the ravine of Jet des Eaux and Riou de l’Aune. The Riss glacier descended to Blegiers; the Würm glaciation was less thick and stopped below Heyre.[4]

The valleys of the southern entrance to the town (Champourcin, Chanolles, Blegiers) are situated in limestone mountains of the Jurassic period. Further upstream and to left bank of the Bléone, the Carton and the Chau ridges are more recent limestone formations of the Upper Cretaceous. In front of these formations at the right bank, the Galabre ridge which separates the Bléone Valley is composed of Bathonian limestone.[5] This has beds of marl, alternating with shallow (less than a meter) limestone and shale marl.[6]

Relief

- Tête de l'Estrop, 2,961 metres (9,715 ft)

- Tête Noire

- Le Caduc

- Col de Talon

Hydrography

The commune is crossed by the Bléone and Galabre.

Environment

The commune has 7,500 hectares (19,000 acres) of woods and forests, or 45% of its area.[2]

Hamlets

- Commune of Prads:

- Prads

- Tercier

- Les Eaux Chaudes (an ancient camp in ruins)

- La Favière

- Former commune of Blégiers:

- Blégiers

- Champourcin

- Chanolles

- Chavailles

- La Colle (uninhabited since 1982)

- Les Combes

- Heyre

- Former commune of Mariaud:

- L’Adrech (uninhabited since 1928)

- L’Immérée (uninhabited since 1914)

- Pré Fourcha (uninhabited since 1934)

- Saume Longue

- Vière (uninhabited since 1934, under restoration)

- Villages and hamlets in Prads-Haute-Bléone

Hamlet of Champourcin

Hamlet of Champourcin Telephone exchange in an old house in Chanolles

Telephone exchange in an old house in Chanolles Hamlet of Chavailles

Hamlet of Chavailles The village of Prads

The village of Prads Washing house of Saume-Longue (Mariaud)

Washing house of Saume-Longue (Mariaud)

Transport

- Roads and bridges in Prads-Haute-Bléone

Old bridge on the Bléone, between Prads and Tercier

Old bridge on the Bléone, between Prads and Tercier Saume-Longue unpaved access road

Saume-Longue unpaved access road The two bridges of Saume-Longue, one above the other, over the Bussing Ravine

The two bridges of Saume-Longue, one above the other, over the Bussing Ravine

Natural and technological hazards

With respect to seismic activity, the area of Prads-Haute-Bléone is in zone 4 (medium risk) according to the probabilistic classification EC8 of 2011.[7]:38 The municipality of Prads-Haute-Bléone is also exposed to three other natural hazards:[8]

- Avalanche (only the Ministry recognises this risk, but not the prefecture)

- Forest fire

- Landslide: mudflows have occurred in the commune after heavy rainfall in July 2005[7]:27

The municipality of Prads-Haute-Bléone is exposed to any of the risks of technological origin identified by the prefecture.[7] The predictable natural risk prevention plan (PPR) of the municipality was approved in 1993 for the risk of land movement; the DICRIM does not exist.[9] The commune was the subject to an avalanche, in 2009.[8] In July 2005, the municipality also had significant mudslides after heavy rains.[10] The following list includes earthquakes felt strongly in the town. They exceed a macro-seismic intensity level V on the MSK scale (sleepers awake, falling objects). The specified intensities are those felt in the town, the intensity can be stronger at the epicentre:[11]

- The earthquake of February 8, 1974, with an intensity level V and with Thorame-Haute and Basse at the epicentre,[12]

- The earthquake of October 31, 1997, with an intensity level VI and whose epicentre was located in the municipality of Prads-Haute-Bléone.[13]

On 5 and 6 November 1968, Prads had one of the first landslides of magnitude which was studied in detail by geomorphologists. It was produced in the Ravin de la Frache[5] (an Occitan term that precisely refers to a zone of talus),[14] in l'Adret and located beneath the summit of Belle Valette.[15]

In the autumn of 1967, already marked by heavy rains, the cracks in the ground expanded. During the winter of 1967-1968, the successions of freeze-thaw lubricated the sliding surfaces. The rainy spring only aggravated the instability of the land. During the autumn 1968 rains, more than a year after the start of the sequence, a flow was triggered[14] resulting in a blackish marl-limestone detrital mass[15] and marl-shale colluvium.[16] If the distance travelled by the flow is reduced (700 m),[17] it carries large blocks and upon arrival, the materials and the largest blocks are very close to the hamlet[16] the entire flow remaining in an unstable state.[18]

Toponymy

The name of the village, as it appears for the first time the 9th century (Colonia in Prato) is derived from the Latin pratum (pré).[19][20] The plural is recent.[19] The Bléone name means Wolf River.

Mariaud appears in the texts at the beginning of the 13th century, but in the form of Mariano: According to Ernest Nègre, the place name derived from the proper Roman name of Marianus, which has evolved from Mariaudo (1319), by attraction to the Provençal local maridado, meaning wedding.[21] Other hypotheses exist.

Blegiers is mentioned for the first time in charters in the second decade of the 12th century, in the form de Bligerio, derived from the Germanic name Blidegar, possibly Latinized as Blidegarius.[22][23]

Chanolles, cited in 1122 (Canola), comes from the Pre-Celtic oronym (mountain toponym) *Kan-.[24]

The name of the summit of Chappe at 1,667 metres (5,469 ft), bordering on Beaujeu, is maintained in the existence of an optical telegraph relay, known as Télégraphe Chappe.[25]

The name of the locality of la Favière evokes a planted field of beans (fèves);[26] that of Combes designates a ravine (similar to combe), downstream of the village of Prads.[27]

Economy

In 2017, the active population amounted to 69 people, including 10 unemployed. These workers are in majority employees (68%), and are in majority employed outside the commune (52%).[28]

At the end of 2015, the primary sector (agriculture, forestry, fishing) had 14 active institutions within the meaning of Insee (including non-professional operators and self-employment).[28]

The number of professional farms, according to the Agreste survey of the Ministry of Agriculture, is nine in 2010. It was 11 in 2000,[29] and 18 in 1988.[30] Currently, these operators are divided into sheep and vegetable farmers.[29] From 1988 to 2000, the usable agricultural land (SAU) had significantly increased, from 943 hectares (2,330 acres) to 1,426 hectares (3,520 acres).[30] The SAU has dropped during the last decade, to 589 hectares (1,460 acres).[29]

At the end of 2015, the secondary sector (industry and construction) had 8 establishments, employing one worker.[28] The hydroelectric power plant of Chanolles used the waters of the Bléone. The turbine had an output of 210kW.[31]

Formerly, hydropower sawmills were installed in Champourcin, Blegiers and Prads. They all ceased operation in the 20th century. In 2013, a new artisanal sawmill was created in the village of Blegiers.[32]

At the end of 2015, the tertiary sector (shops, transport, services) had eight institutions (one salaried employee), in addition to seven institutions in the administrative sector (together with the health and social sector and education), with six people employed.[28] According to the Observatoire départemental du tourisme, the tourist function is very important for the municipality, with more than five tourists accommodated per capita,[33] despite a low capacity of accommodation for tourist purposes:

- Several branded as furnished[34] and a number non-furnished.[35]

- The only capacity for any collective accommodation is located in the shelters.[36]

Secondary residences complement the capacity:[37] with a number of 212, they represent 65% of dwellings.[28][38]

The bistro at the Trois Évêchés, which carries the Bistrot de Pays brand,[39] adheres to a charter which aims to "contribute to the conservation and the animation of the economic and social fabric in rural areas by maintaining a place in village life".[40]

There is also a centre for excursions and hikes.

History

In ancient times, Bodiontiques (Bodiontici) lived in the Valley of the Bléone, and were therefore the Gallic people who lived in the valleys of the current commune of Prads-Haute-Bléone. The Bodiontiques, who were defeated by Augustus at the same time as other peoples present on the Trophy of the Alps (before 14 BC) are attached to the Roman province of Alpes Maritimae at its inception.[41]

The communities of Blegiers, Champourcin, Chanolles, Chavailles, Mariaud and Prads were all of the Bailli of Digne.[42]

Prads

The locality of Prads appears for the first time in charters in the High Middle Ages, as Prato, dependent upon the Abbey of Saint Victor in Marseille.[42] It stood at the junction of the dioceses of Digne, Senez, and Embrun.[43]

The Abbey of Cistercian monks of Notre-Dame de Faillefeu (or meadows: the Abbot was called "the Abbot of the meadows")[44] was founded in 1144[43] by the monks of Boscodon.[42] They founded the Abbey of Valbonne[42] on February 3, 1199 (the date of the Charter of Foundation).[44] In 1298, it belongs to the Cluny Abbey, and then passes under the authority of the college Saint-Martial in Avignon. The abbey was eventually looted, ransacked and abandoned during the French Wars of Religion.[42]

The tithes were levied by the Chapter of Digne.[42]

In 1843, the priest of the parish, Paul Charpenel, writes the annals of the parish of Prads, not published to date.[42] One of the municipal measures from this period is the construction of a public fountain in the village, under the Second Republic, in 1850.

The coup d'état of 2 December 1851 by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte against the Second Republic caused an armed uprising in the Basses-Alpes, in defense of the constitution. After the failure of the uprising, severe repression descended on those who stood up to defend the Republic, which included an inhabitant of Prads.[45]

As with many municipalities of the department, Prads acquired schools well before the Jules Ferry laws: in 1863, it had three, located in Prads, la Favière and Tercier. These schools provided a primary education to boys.[46] While the Falloux Laws of 1851, required the opening of a girls school in communes with more than 800 inhabitants, Prads maintained a girls school in the 1860s,[47] but that school closed before the end of the Second Empire.[48] It is only since the Ferry Laws that Prads girls have attended school regularly.

Blégiers

In the Middle Ages, during the 12th century, the village of Blégiers (Bligerium) moved to the Roche-de-Blégiers, on a hilltop site.[42] The community had a consulate in the 13th century.[49] Its population increased from 81 feus in 1315, with another 14 in 1471. At this time, it was still part of the Chapter of Digne that owned the domain and the Church of the Roche-de-Blégiers, before selling these in 1476 to the Bishop of Digne. From that date, it was the Bishop who appointed the responsible chaplain of the souls of this parish, and who collects revenues attached to this church.[42]

Chanolles was reported as early as 814: The Polyptych of Wadalde indicated that the Abbey of Saint Victor in Marseille had a Cour colongère.[42] The two communities of Chanolles and Champourcin which had eight feus each count of 1315, were heavily depopulated by the crises of the 14th century (the Black Death and the Hundred Years' War), and were annexed by Blegiers in the 15th century.[50] Champourcin and Chanolles churches were of the chapter of Digne.[42]

The death of Queen Jeanne I opened a succession crisis in the Comté de Provence, the towns of the Union of Aix (1382-1387), supported Charles, Duke of Durazzo against Louis I, Duke of Anjou. The Lord of Chanolles, Louis le Roux, supported the Duke of Anjou as early as April 1382, this support was conditional on the participation of the Duke in the relief expedition to the Queen.[51] The Lord of Blegiers, Louis Aymes, appears in the lists of support to the Angevins in 1385, after the death of Louis I.[52]

In 1765, Blégiers had 257 inhabitants. The lordship of the place had belonged successively to the Grimaldi (14th century), Puget and Eissautier families.[50]

As Prads, Blégiers acquired schools well before the Jules Ferry laws: In 1863, it had four installed in Blégiers and the villages of Heyres, Chanolles and Chavailles. These schools provided a primary education to boys.[46] No instruction was given to girls, nor under the Falloux Laws of 1851, which required the opening of a girls school in the communes with more than 800 inhabitants,[47] nor did the first Duruy Law (1867), which lowered the threshold to 500 inhabitants, concern Blegiers.[48] The commune took advantage of subsidies from the second Duruy Law (1877) to build new schools everywhere. Only the Blegiers school was renovated.[53] It is only with the Ferry Laws that girls became educated regularly.

While the settlement was isolated, polyculture allowed most of the needs to be met. Wine was produced locally, but had a poor reputation. A polyculture, the highest in the Bléone Valley, was abandoned before World War I.[54] The decline of self-sufficient polyculture continued after World War II, and harvesting wheat was stopped in 1958.[55]

Mariaud

The community of Mariaud appears in texts in 1218 (Mariaudum). With a consul from 1237, it had 50 feus in 1315, but only 10 by 1471.[56] The Church of Mariaud reported to the Abbey of Saint-Ruf in Valence, but it was the Prior of Beaujeu, who collected the tithe.[42]

In the conflict between Charles, Duke of Durazzo and Louis I, Duke of Anjou in the succession of Jeanne I, the Lord of Mariaud, Gui de Saint-Marcial, supported Louis as the Duke of Anjou from the spring of 1382.[51]

It had 195 inhabitants in 1765.[56]

As Prads and Blégiers, Mariaud acquired a school well before the Jules Ferry laws, for the hamlet of Vière.[46] Also as with Blégiers and Prads, no instruction was given to girls by the Falloux Laws of 1851,[47] and nor did the first Duruy Laws of 1867 apply to Mariaud.[48] Again, it was with the Ferry Laws that Mariaud girls became educated regularly.

In 1939, after displacement of the village, the main settlement became Vière at Saume Longue.[57]

French Revolution

During the French Revolution, the communes of Blegiers and Prads each had a patriotic society, both created after the end of 1792.[58]

Contemporary period

- The war memorials of the two world wars and other memorials of the commune

Façade of the Church of Chanolles, to which is attached the plate bearing the names of the inhabitants of this commune who died in World War I

Façade of the Church of Chanolles, to which is attached the plate bearing the names of the inhabitants of this commune who died in World War I Monument to the dead of Mariaud

Monument to the dead of Mariaud Monument to the dead of Prads

Monument to the dead of Prads Sign commemorating the attack on the PC of the Organisation de résistance de l'armée (ORA, part of the FFI)

Sign commemorating the attack on the PC of the Organisation de résistance de l'armée (ORA, part of the FFI) Stele commemorating the passage of the Foreign Legion

Stele commemorating the passage of the Foreign Legion The flightpath to the crash of the A320 Airbus in 2015

The flightpath to the crash of the A320 Airbus in 2015

On 30 July 1944, the hamlet of Eaux-Chaudes was burned by the Wehrmacht. From 1954 to 1959 the Foreign Legion set up a camp at a place called Les Eaux-Chaudes, which hosted 30 legionaries. This camp is now in ruins.[59]

The town of Prads merged with that of Mariaud in 1973. That of Blégiers joined them in 1977, and the commune was renamed Prads-Haute-Bléone.[60]

On 24 March 2015, Germanwings Flight 9525, an Airbus A320 flying from Barcelona to Düsseldorf, crashed in the mountains within the territory of the commune, killing all 150 passengers and crew. It has been described as the 'French Lockerbie bombing'.

Heraldry

Arms of Prads-Haute-Bléone |

The arms of Prads-Haute-Bléone are blazoned: Gold to a fess of azure accompanied by six trefoils vert, ranked three in chief and three in base.[61] |

Politics and administration

| Start | End | Name | Party | Other details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the post in 1829 | Still in the post in 1838 | Antoine Segond[42] | Known as Toniou | |

| ... | ||||

| In the post in 1944 | Adrien Roux[59] | |||

| May 1945 | Joseph Garcin[62] | |||

| ... (?) | ||||

| 1983 (?) | In progress (as of 21 October 2014) | Bernard Bartolini[63][64][65] | RPR | Restaurant owner |

The premises of the school of Blegiers contains the municipal library.[66]

Demography

Prads and Prads-Haute-Bléone

In 2012, Prads-Haute-Bléone had 186 inhabitants. From the 21st century, places with less than a population of 10,000 have had a census every five years (2007, 2012, 2017, etc. for Prads-Haute-Bléone). Since 2004, the other figures are estimates.

The municipality had 180 inhabitants in 1990 against 980 for the three communes of Blegiers, Mariaud and Prads[67] in 1881. All of the three communes experienced a population peak in the 1830s with 1294 inhabitants in 1836.

The table and chart that follow relate to the population of the municipality of Prads until 1968, then the new municipality of Prads (with Mariaud) in 1975, and finally Prads-Haute-Bléone (with Blegiers) from 1982.

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population without double counting from 1962 to 1999; municipal population from 2006 Source: Cassini of the EHESS until 1962;[60] INSEE from 1968[68] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the 19th century, after a period of growth, Prads showed a 'slack' period where the population remained relatively stable at a level high. This period lasted from 1811 to 1851. The rural exodus then caused a movement of long-term demographic decline. By 1921, the municipality records the loss of more than half of its population over the historic high of 1836.[69] The downward movement stops definitively than in the 1960s. Since then, the population has resumed some growth.

Blégiers demographics

For the enumeration of 1315, Blegiers, Chanolles, and Champourcin populations were added together.

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population without double counting from 1962 onwards. Source: Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer for the Ancien Régime;[50] EHESS[70] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The demographic history of Blegiers is marked by the loss of population during the 14th and 15th centuries due to the Black Death and the Hundred Years' War, crises which completely destroyed the communities of Chanolles and Champourcin and also touched that of Blegiers, strongly.

In the 19th century, after a period of growth, Blegiers had a 'slack' period where the population remained relatively stable at a level high. This period lasted from 1821 to 1851. The rural exodus then caused a faster long-term decline than in Prads. By 1906, the settlement had lost more than half of its population, since the historic maximum in 1836.[69] The downward movement continued until the 1970s and the merger with Prads.

Mariaud demographics

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population without double counting from 1962 onwards. Source: Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer for the Ancien Régime;[56] EHESS[71] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Just like Blegiers, Mariaud is marked by a loss of population during the 14th and 15th centuries due to the Black Death and the Hundred Years' War, and lost 80% of its population between 1315 and 1471. However, the depopulation crisis had been over for several decades by 1471.

In the 19th century, after a period of growth, Mariaud shows a period of 'slack' for longer than its neighbours, from 1806 to 1866. Though, if the rural exodus began here later, it affected Mariaud, Blegiers and Prads with equal strength. In 1911, the town had lost more than half its population compared to the historical maximum of 1831.[69] The downward movement continued until the 1960s and brought about the merger with Prads.

Sites and monuments

Natural places

The RD107 road offers beautiful panoramic views.

Churches and chapels

The Sainte-Anne Parish Church of Prads, which dates from the 14th century, was entirely rebuilt in 1876-1878, and repaired in 1888. The nave, long with three bays, leads into a chancel of false-style Gothic.[72] It is oriented to the north-west.

The Abbey of Sainte-Marie-de-Villevieille, known as Faillefeu or Prads[73] was built in the middle of the 12th century by the monks of Boscodon, which was then given to the Abbey of Cîteaux. The priory was then dependent on Cluny.[73] The church has collapsed completely and is a pile of earth and stone, between the monastic buildings still standing.[74]

- Churches and chapels of Prads-Haute-Bléone

The church of Our Lady of Blégiers, decrepit in 2012

The church of Our Lady of Blégiers, decrepit in 2012 The interior of Our Lady of Blégiers

The interior of Our Lady of Blégiers The church of Saint-Jean-Baptiste of Chanolles, north wall

The church of Saint-Jean-Baptiste of Chanolles, north wall Façade and bell tower of the Church of Saint-Laurent of Chavailles

Façade and bell tower of the Church of Saint-Laurent of Chavailles The church of Sainte-Anne of Prads

The church of Sainte-Anne of Prads Façade of the Church of Saint-Étienne of Mariaud

Façade of the Church of Saint-Étienne of Mariaud Façade of the Church of Our Lady of Beauvezer, in Champourcin

Façade of the Church of Our Lady of Beauvezer, in Champourcin

The commune of Prads-Haute-Bléone gathers three old communes and six medieval communities, which explains the large number of religious buildings that are found in its territory:

- The Chapel of Our Lady at Tercier, rebuilt by the inhabitants in 1829.[42]

- The Church of Our Lady at Blegiers, which was originally a small chapel is much extended around 1830[42][75] with the ancient Saint-Barbara's Chapel being converted into a sacristy.[42] The bell tower was rebuilt in 1877.[75]

- The Heyres Saint-Roch Chapel, which was a branch of Our Lady at Blegiers, was restored in 1982. It is built at an altitude of 1,200 metres (3,900 ft).[42]

- The Church of Saint-Jean-Baptiste (rebuilt in 1810, restored in 1865)[75] at Chanolles, with a statue of St. John from the 15th century, carved, painted wooden and classified.[76] Its bell tower dates from the end of the 19th century.[42]

- The Church of Saint-Laurent at Chavailles (formerly Saint-Sauveur)[42] was rebuilt in 1842[75] after being originally built in the 13th century. The bell tower dates from the Second Empire.[42] In the church furniture, a silver ciborium dated from the 17th century (classified as a Monument historique object).[77] Its small processional cross, silver, dates from the 18th century and is also classified.[78]

- The old Church of Our Lady of Beauvezer[42] in Champourcin (the chalice and the paten of silver, from the 17th century, are classified).[79]

- At the village of Champourcin, Saint-Christophe's Church is installed in a basement, with a bell tower in the garden.[42]

- The Chapel of Our Lady of the Transfiguration, in the hamlet of la Favière, rebuilt in 1838. The Church was the seat of a parish in the 14th century, the presbytery dates from the beginning of the 1870s, the bell tower of the 1880s.[42]

- The ruins of the Church of Saint-Étienne of Vière (Romanesque, built in the 13th century[42] with ongoing restoration since 2011), in the former village of Mariaud. The cobbles of the parvise of the Church of Saint-Étienne draws a Jerusalem cross inscribed in a Reuleaux triangle.

- Artwork and furniture within the churches of Prads-Haute-Bléone

Transfiguration at Blégiers

Transfiguration at Blégiers Assumption at Chavailles

Assumption at Chavailles The Holy family around the carpenter's workbench with traditional tools

The Holy family around the carpenter's workbench with traditional tools Banner of procession to the Church Saint-Laurent of Chavailles

Banner of procession to the Church Saint-Laurent of Chavailles Medieval baptismal font of Prads

Medieval baptismal font of Prads

Castle

The Château de Mariaud is in a state of ruin.[42]

Notable people

This is the village of Christian Garcin's father, the writer frequently spends his summer vacation here. Jean Taxis was an 18th-century businessman who was born in Blégiers.

See also

- Communes of the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence department

- List of ancient communes in Alpes-de-Haute-Provence

- Vallée de la Haute Bléone

Books

- Baume, Marie-Paule (2011). La Bléone et Faillefeu [The Bléone and Faillefeu] (in French). ISBN 978-2-85301-078-8.

This book, very well documented, traces the history of the ancient Abbey of Faillefeu and the exploitation of the homonymous forest. The author cites ancient families involved in the logging and transport of logs floated along the Bléone Valley.

- Nakul, Geneviève; Baume, Marie-Paule (2012). Le Manuscrit de Mariaud 1680-1828 [The manuscript of Mariaud 1680-1828] (in French).

This book is the transcription of the book by reason of a family of farmers, over 6 generations, living in the hamlet of Adret, within the former commune of Mariaud. It traces mainly baptisms and the accounts of the household, as well as important transactions received before a notary.

Bibliography

- Collier, Raymond (1986). La Haute-Provence monumentale et artistique [La Haute-Provence monumental and artistic] (in French). Digne: Imprimerie Louis Jean.

- Baratier, Édouard; Duby, Georges; Hildesheimer, Ernest (1969). Atlas historique. Provence, Comtat Venaissin, principauté d'Orange, comté de Nice, principauté de Monaco [Historical Atlas. Comtat Venaissin, Principality of Orange, County of Nice, Provence, Principality of Monaco] (in French). Paris: Librairie Armand Colin. (BnF no. FRBNF35450017h)

References

- "Populations légales 2017". INSEE. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Canton de La Javie". Le Trésor des régions. Roger Brunet. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Service de Géodésie et Nivellement - RN : I'.A.K3 - 31". Archived from the original on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Michel d’Annoville, Nicole; de Leeuw, Marc (2008). Les Hautes Terres de Provence : itinérances médiévales [Highlands of Provence: medieval roaming] (in French). Saint-Michel-l'Observatoire. p. 33. ISBN 978-2-952756-43-3.

- "Le glissement de terrain de Prads (novembre 1968) et ses enseignements morphologiques" [The sliding of land of Prads (November 1968) and its morphological teachings] (in French). p. 193. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Le glissement de terrain de Prads (novembre 1968) et ses enseignements morphologiques" [The sliding of land of Prads (November 1968) and its morphological teachings] (in French). p. 203. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Dossier départemental des risques majeurs" (PDF). 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "Notice communale". 27 May 2011. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- "Document d'Information Communal sur les Risques Majeurs". Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Préfecture des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, DDRM, op. cit., p. 33.

- "PRADS-HAUTE-BLEONE (04155)". Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "PREALPES DE DIGNE (THORAME) − ALPES PROVENCALES". Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "PREALPES DE DIGNE (PRADS-HAUTE-BLEONE) − ALPES PROVENCALES". Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Le glissement de terrain de Prads (novembre 1968) et ses enseignements morphologiques" [The sliding of land of Prads (November 1968) and its morphological teachings] (in French). p. 204. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Le glissement de terrain de Prads (novembre 1968) et ses enseignements morphologiques" [The sliding of land of Prads (November 1968) and its morphological teachings] (in French). p. 194. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Le glissement de terrain de Prads (novembre 1968) et ses enseignements morphologiques" [The sliding of land of Prads (November 1968) and its morphological teachings] (in French). p. 201. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Le glissement de terrain de Prads (novembre 1968) et ses enseignements morphologiques" [The sliding of land of Prads (November 1968) and its morphological teachings] (in French). p. 195. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Le glissement de terrain de Prads (novembre 1968) et ses enseignements morphologiques" [The sliding of land of Prads (November 1968) and its morphological teachings] (in French). p. 206. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Nègre, Ernest (1990). Toponymie générale de la France : étymologie de 35 000 noms de lieux: Formations préceltiques, celtiques, romanes. 1. Geneva: Librairie Droz. p. 347. ISBN 978-2-600-02884-4.

- Fénié, Bénédicte; Fénié, Jean-Jacques (2002). Toponymie provençale. Éditions Sud-Ouest. p. 69. ISBN 978-2-87901-442-5.

- Nègre, Ernest (1990). Toponymie générale de la France : étymologie de 35 000 noms de lieux: Formations préceltiques, celtiques, romanes. 1. Geneva: Librairie Droz. p. 662. ISBN 978-2-600-02884-4.

- Nègre, Ernest (1996). Toponymie générale de la France : étymologie de 35 000 noms de lieux: Formations non-romanes ; formations dialectales. 2. Geneva: Librairie Droz. p. 831. ISBN 978-2-600-00133-5.

- Fénié, Bénédicte; Fénié, Jean-Jacques (2002). Toponymie provençale. Éditions Sud-Ouest. p. 70. ISBN 978-2-87901-442-5.

- Fénié, Bénédicte; Fénié, Jean-Jacques (2002). Toponymie provençale. Éditions Sud-Ouest. p. 22. ISBN 978-2-87901-442-5.

- Fénié, Bénédicte; Fénié, Jean-Jacques (2002). Toponymie provençale. Éditions Sud-Ouest. p. 83. ISBN 978-2-87901-442-5.

- Fénié, Bénédicte; Fénié, Jean-Jacques (2002). Toponymie provençale. Éditions Sud-Ouest. p. 101. ISBN 978-2-87901-442-5.

- Fénié, Bénédicte; Fénié, Jean-Jacques (2002). Toponymie provençale. Éditions Sud-Ouest. p. 87. ISBN 978-2-87901-442-5.

- Dossier complet: Commune de Prads-Haute-Bléone (04155)

- "Ministère de l'Agriculture: Orientation technico-économique de l'exploitation, Recensements agricoles 2010 et 2000". Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Exploitations agricoles en 1988 et 2000". Insee. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Ruillet, Mathieu; Ruchet, Éric. Étude du potentiel régional pour le développement de la petite hydroélectricité. Groupe énergies renouvelables, environnement et solidarité (GERES). p. 60.

- D. Ch., « À Blégiers, les Giroux et le bois c'est une affaire de famille », La Provence, 5 mars 2013, p. 4.

- "Atlas de l'hébergement touristique" (PDF). Observatoire départemental du tourisme. p. 6. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Atlas de l'hébergement touristique" (PDF). Observatoire départemental du tourisme. p. 32. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Atlas de l'hébergement touristique" (PDF). Observatoire départemental du tourisme. p. 36. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Atlas de l'hébergement touristique" (PDF). Observatoire départemental du tourisme. p. 30. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Atlas de l'hébergement touristique" (PDF). Observatoire départemental du tourisme. p. 44. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Hébergements touristiques des communes, 2008, 2009 et 2012". Insee. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "La charte Bistrot de Pays". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- "L'implantation des Bistrots de pays en France métropolitaine en 2010".

- Brigitte Beaujard, «Les cités de la Gaule méridionale du IIIe au VIIe s.», Gallia, 63, 2006, CNRS éditions, p. 22.

- "Prads Haute-Bléone". archeoprovence.com. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Baratier, Duby et Hilsdesheimer, op. cit., carte 77 Ordre divers (XIIe-XIVe siècle)

- "Le consulat de Reillanne au début du XIIIe siècle" (PDF). Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Henri Joannet, Jean-Pierre Pinatel, « Arrestations-condamnations », 1851-Pour mémoire, Les Mées : Les Amis des Mées, 2001, p. 72.

- Labadie, Jean-Christophe (2013). Les Maisons d'école. Digne-les-Bains: Archives départementales des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. p. 9. ISBN 978-2-86-004-015-0.

- Labadie, Jean-Christophe (2013). Les Maisons d'école. Digne-les-Bains: Archives départementales des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. p. 16. ISBN 978-2-86-004-015-0.

- Labadie, Jean-Christophe (2013). Les Maisons d'école. Digne-les-Bains: Archives départementales des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. p. 18. ISBN 978-2-86-004-015-0.

- Édouard Baratier, « carte 45 : Les consulats de Provence et du Comtat (XIIe-XIIIe siècles) », in Atlas historique de la Provence

- Baratier, Édouard; Duby, Georges; Hildesheimer, Ernest (1969). Atlas historique. Provence, Comtat Venaissin, principauté d'Orange, comté de Nice, principauté de Monaco. Paris: Librairie Armand Colin. p. 165.(notice BnF no FRBNF35450017h)

- "Partisans et adversaires de Louis d'Anjou pendant la guerre de l'Union d'Aix". Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Partisans et adversaires de Louis d'Anjou pendant la guerre de l'Union d'Aix". p. 412. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Labadie, Jean-Christophe (2013). Les Maisons d'école. Digne-les-Bains: Archives départementales des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. p. 11. ISBN 978-2-86-004-015-0.

- Minvielle, Paul (2006). La viticulture dans les Alpes du Sud entre nature et culture. Méditerranée, 107. p. 77.

- Gaillard, Élie-Marcel (February 1997). Au temps des aires: battre, dépiquer, fouler. Alpes de Lumière. p. 49. ISBN 2-906162-33-7.

- Baratier, Édouard; Duby, Georges; Hildesheimer, Ernest (1969). Atlas historique. Provence, Comtat Venaissin, principauté d'Orange, comté de Nice, principauté de Monaco. Paris: Librairie Armand Colin. p. 181.(notice BnF no FRBNF35450017h)

- Nucho, Philippe (1993). Les structures territoriales des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. Digne-les-Bains: éditions de Haute-Provence. p. 63. ISBN 2-909800-07-5.

- Patrice Alphand, «Les Sociétés populaires», La Révolution dans les Basses-Alpes, Annales de Haute-Provence, bulletin de la société scientifique et littéraire des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, no 307, 1er trimestre 1989, 108e année, p. 296-298.

- D. Ch., « Souvenir des légionnaires aux Eaux-Chaudes », La Provence, le 8 mai 2013, p. 4

- Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Prads-Haute-Bléone, EHESS. (in French)

- Louis de Bresc, Armorial des communes de Provence, 1866. Réédition : Marcel Petit CPM, Raphèle-lès-Arles, 1994.

- "LA LIBÉRATION". basses-alpes39-45.fr. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Bernard Bartolini is one of 500 elected representatives who sponsored the candidacy of Jacques Chirac (RPR) in the 1988 presidential election. Liste des citoyens ayant présenté les candidats à l'élection du Président de la République [List of citizens who have submitted candidates for the election of the President of the Republic]. Journal officiel de la République française du 12 avril 1988 (in French). Conseil constitutionnel. p. 4792. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "De Montfuron à Puimichel (liste 5)". Préfecture des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Préfecture des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, « Liste des maires Archived 2014-10-22 at the Wayback Machine », 2014, consultée le 20 octobre 2014.

- Labadie, opcit, p.56.

- "Bulletin municipal de Prads". Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Population en historique depuis 1968, INSEE

- Vidal, Christiane (1971). "Chronologie et rythmes du dépeuplement dans le département des Alpes de Haute- Provence depuis le début du XIX' siècle" [Timeline and rhythms of the depopulation in the Department of Alpes de Haute-Provence since the beginning of the 19th century] (in French). 21 (85). Provence historique: 287. Retrieved 30 March 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Blégiers, EHESS. (in French)

- Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Mariaud, EHESS. (in French)

- Collier, Raymond (1986). La Haute-Provence monumentale et artistique. Digne: Imprimerie Louis Jean. p. 389.

- Morel, Jacques (1999). Guides des Abbayes et des Prieurés: chartreuses, prieurés, couvents. Centre-Est & Sud-Est de la France. Paris: Éditions aux Arts. p. 64. ISBN 2-84010-034-7.

- Collier, Raymond (1986). La Haute-Provence monumentale et artistique. Digne: Imprimerie Louis Jean. p. 143.

- Collier, Raymond (1986). La Haute-Provence monumentale et artistique. Digne: Imprimerie Louis Jean. p. 379.

- Base Palissy: PM04000844, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Base Palissy: PM04000845, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Base Palissy: PM04000847, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Base Palissy: PM04000848, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)