Red-necked wallaby

The red-necked wallaby or Bennett's wallaby (Macropus rufogriseus) is a medium-sized macropod marsupial (wallaby), common in the more temperate and fertile parts of eastern Australia, including Tasmania. Red-necked wallabies have been introduced to several other countries, including New Zealand, the United Kingdom (in England and Scotland), Ireland, the Isle of Man, France and Germany.[3]

| Red-necked wallaby[1] or Bennett's wallaby | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bennett's wallaby (M. r. rufogriseus), Bruny Island, Tasmania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Macropodidae |

| Genus: | Macropus |

| Subgenus: | Notamacropus |

| Species: | M. rufogriseus |

| Binomial name | |

| Macropus rufogriseus (Desmarest, 1817) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Bennett's wallaby (M. r. rufogriseus) | |

| |

| Red-necked wallaby's native range | |

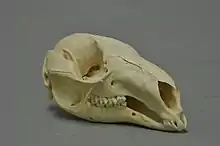

Description

Red-necked wallabies are distinguished by their black nose and paws, white stripe on the upper lip, and grizzled medium grey coat with a reddish wash across the shoulders. They can weigh 13.8 to 18.6 kilograms (30 to 41 lb) and attain a head-body length of 90 centimetres (35 in), although males are generally bigger than females. Red-necked wallabies are very similar in appearance to the black-striped wallaby (Macropus dorsalis), the only difference being that red-necked wallabies are larger, lack a black stripe down the back, and have softer fur.[4] Red-necked wallabies may live up to 9 years.[5]

Distribution and habitat

Red-necked wallabies are found in coastal scrub and sclerophyll forest throughout coastal and highland eastern Australia, from Bundaberg, Queensland to the South Australian border;[5] in Tasmania and on many of the Bass Strait islands. It is unclear which of the Tasmanian islands have native populations as opposed to introduced ones.

In Tasmania and coastal Queensland, their numbers have expanded over the past 30 years because of a reduction in hunting pressure and the partial clearing of forest to result in a mosaic of pastures where wallabies can feed at night, alongside bushland where they can shelter by day. For reasons not altogether clear, they are less common in Victoria.

Behaviour

Red-necked wallabies are mainly solitary but will gather together when there is an abundance of resources such as food, water or shelter. When they do gather in groups, they have a social hierarchy similar to other wallaby species. A recent study has demonstrated that wallabies, as other social or gregarious mammals, are able to manage conflict via reconciliation, involving the post-conflict reunion, after a fight, of former opponents, which engage in affinitive contacts.[6] Red-necked wallabies are mainly nocturnal. They spend most of the daytime resting.[5]

A female's estrus lasts 33 days.[5] During courting, the female first licks the male's neck. The male will then rub his cheek against the female's. Then the male and female will fight briefly, standing upright like two males. After that they finally mate. A couple will stay together for one day before separating. A female bears one offspring at a time; young stay in the pouch for about 280 days,[7] after which females and their offspring stay together for only a month. However, females may stay in the home range of their mothers for life, while males leave at the age of two. Also, red-necked wallabies engage in alloparental care, in which one individual may adopt the child of another. This is a common behavior seen in many other animal species like wolves, elephants, and fathead minnows.[8]

Diet

Red-necked wallabies diets consists of grasses, roots, tree leaves, and weeds.[5]

Subspecies

There are three subspecies.

- red-necked wallaby (M. r. banksianus) (Quoy & Gaimard, 1825)

- M. r. fruticus (Ogilby, 1838)

- Bennett's wallaby (M. r. rufogriseus) (Desmarest, 1817)

The Tasmanian subspecies, Macropus rufogriseus rufogriseus, usually known as Bennett's wallaby, is smaller (as island subspecies often are), has longer, darker[4] and shaggier fur, and breeds in the late summer, mostly between February and April. They have adapted to living in proximity to humans and can be found grazing on lawns in the fringes of Hobart and other urban areas.

The mainland Australian subspecies, Macropus rufogriseus banksianus, usually known as the red-necked wallaby, breeds all year round. Captive animals maintain their breeding schedules; Tasmanian females that become pregnant out of their normal season delay birth until summer, which can be anywhere up to 8 months later.

Introductions to other countries

There are significant introduced populations in the Canterbury region of New Zealand's South Island. In 1870, several Bennett's wallabies were transported from Tasmania to Christchurch, New Zealand. Two females and one male from this stock were later released about Te Waimate, the property of Waimate's first European settler Michael Studholme. The year 1874 saw them freed in the Hunters Hills, where over the years their population has dramatically increased. Bennett's wallabies are now resident on approximately 350,000 ha of terrain centred upon the Hunters Hills, including the Two Thumb Ranges, the Kirkliston Range and the Grampians. They have been declared an animal pest in the Canterbury region and land occupiers must contain the wallabies within specified areas.[9] Bennett's wallaby is now widely regarded as a symbol of Waimate.

There are also colonies in England[5] in the Peak District, Derbyshire, and the Ashdown Forest in East Sussex. These were established ca. 1900. There are also other smaller groups frequently spotted in West Sussex and Hampshire.

There is a small colony of red-necked wallabies on the island of Inchconnachan, Loch Lomond in Argyll and Bute, Scotland. This was founded in 1975 with two pairs taken from the Whipsnade Zoo, and had risen to 26 individuals by 1993.[10]

There is a large group of approximately 250 red-necked wallabies living wild on the Isle of Man, which are the descendants of a pair that escaped from a wildlife park on the island in the 1970s,[11] as well as from subsequent escapes.[12]

The Baring family, who owned Lambay Island (250 ha (620 acres)), off the eastern coast of Ireland introduced red-necked wallabies to the island in the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1980s, the red-necked wallaby population at the Dublin Zoo was growing out of control. Unable to find another zoo to take them, and unwilling to euthanize them, zoo director Peter Wilson donated seven individuals to the Barings. The animals have thrived since then and the current population is estimated to be between 30 and 50.[13]

In France, in the southern part of the Forest of Rambouillet, 50 km (31 mi) west from Paris, there is a wild group of around 50-100 Bennett's wallabies. This population has been present since the 1970s, when some individuals escaped from the zoological park of Émancé after a storm.[14]

In Germany, around 10 wallabies live as a wild population in the federated state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern since 2001.[15]

In October 2014, three captive Bennett's wallabies escaped into the wild in northern Austria and one of them roamed the area for three months before being recaptured, surprisingly surviving the harsh winter there. The case attracted media attention, as it humorously defeated the popular slogan "There are no kangaroos in Austria."[16]

Gallery

A joey in a pouch

A joey in a pouch A juvenile Bennett's wallaby (M. r. rufogriseus)

A juvenile Bennett's wallaby (M. r. rufogriseus) A red-necked wallaby (M. r. banksianus)

A red-necked wallaby (M. r. banksianus)

References

- Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Diprotodontia". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- McKenzie, N.; Menkhorst, P. & Lunney, D. (2008). "Macropus rufogriseus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- Dickinson, Greg. "The curious mystery of the wild wallabies living on the Isle of Man". The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- Staker, Lynda (2006). The Complete Guide to the Care of Macropods. Lynda Staker. p. 54. ISBN 0977575101.

- Long, John (2003). Introduced Mammals of the World. Csiro Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 0643099166.

- Cordoni, G., Norscia, I., 2014: Peace-Making in Marsupials: The First Study in the Red-Necked Wallaby (Macropus rufogriseus) PLOS One 9(1): e86859. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086859

- "Bennett's Wallaby - Encyclopedia of Life".

- Riedman, Marianne L. (December 1982). "The Evolution of Alloparental Care in Mammals and Birds". The Quarterly Review of Biology 57 (4): 405-435

- Law, Tina (28 March 2014). "Big bounce in South Island wallaby numbers". Stuff. Stuff. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "The Colquhoun's Island". Inchconnachan Island - Loch Lomond. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- Normand, Jacey (17 October 2010). "Searching for the Isle of Man's wild wallabies". BBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- Havlin, Paige (8 August 2016). "Myths surrounding Isle of Man's wild wallabies". Isle of Man Today. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- Connolly, Colleen (12 November 2014). "What the Heck Are Wallabies Doing in Ireland?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "Enquête sur le Wallaby de Bennett en Forêt d'Yvelines" [Investigation of Bennett's Wallaby in the Yvelines Forest]. CERF78 (in French). 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- as of 2. Dezember 2014.

- "Runaway 'kangaroo' spotted in garden". The Local.at. 28 January 2015.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Macropus rufogriseus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Macropus rufogriseus. |

External links

Further reading

- Latham, A. David M.; Latham, M. Cecilia; Warburton, Bruce (11 June 2018). "Current and predicted future distributions of wallabies in mainland New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. Informa UK Limited. 46 (1): 31–47. doi:10.1080/03014223.2018.1470540. ISSN 0301-4223.

- English, Holly M.; Caravaggi, Anthony (2 November 2020). "Where's wallaby? Using public records and media reports to describe the status of red‐necked wallabies in Britain". Ecology and Evolution. Wiley. doi:10.1002/ece3.6877. ISSN 2045-7758.

- Bentley, Ross (18 August 2018). "Could wallabies be about to colonise north Essex?". East Anglian Daily Times. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- McCarthy, Michael (20 February 2013). "The decline and fall of the Peak District wallabies". The Independent. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Caravaggi, Anthony; English, Holly (3 November 2020). "Wallabies are on the loose in Britain – and we've mapped 95 sightings". The Conversation. Retrieved 12 November 2020.