Seth Ledyard Phelps

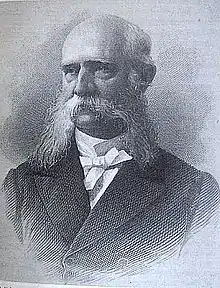

Seth Ledyard Phelps (January 13, 1824 – June 24, 1885[lower-alpha 1]) was an American naval officer, and in later life, a politician and diplomat. Phelps received his first commission in United States Navy as a midshipman aboard the famous USS Independence. He served patrolling the coast of West Africa guarding against slavers. During the Mexican–American War he served on gunboats, giving support to Winfield Scott's army, and later served in the Mediterranean and Caribbean squadrons.

Seth Ledyard Phelps | |

|---|---|

Seth L. Phelps | |

| Born | January 13, 1824 Parkman, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | June 24, 1885 (aged 61) Lima, Peru |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1841–1864 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | Mississippi River Squadron |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War |

| Other work |

|

During the American Civil War Phelps advanced to the rank of Lieutenant commander and served with distinction during the Mississippi River campaigns. He was noted for his familiarity of the river systems in the Western theater and conducted several reconnaissance missions, discovering the presence of Confederate Fort Donelson, in Tennessee. He commanded squadrons of gunboats on the Mississippi, Tennessee and Cumberland rivers and played key roles in the riverboat assaults during the various battles in the river campaigns, often supporting Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman and other Generals with their troop deployments on land. For his service Phelps received much praise in various prominent newspapers. As a young commander, Phelps was an outspoken critic of the Navy's method of promotion that favored seniority over military experience and capability. As Phelps served with every flag officer and fleet commander on the Mississippi and Tennessee Rivers during the Civil War,[lower-alpha 2] his biography provides an almost continuous account of the naval engagements that occurred in the Trans-Mississippi Theater during that war. In later life Phelps was on the Board of Commissioners and was its first president, and later, U.S. Minister to Peru.

Early life

Seth Phelps was named after his grandfather, who served in the American Revolutionary War and at times with George Washington and was present at Valley Forge. The senior Seth was later promoted to captain and became an aide to General Washington.[2] Seth Ledyard's father's name was Alfred Phelps, who served in the War of 1812 under Winfield Scott in the Battle of Queenston Heights in Ontario. After the war Alfred returned home, started a law practice, and then met and married Ann B. Towsley on July 1, 1820. Shortly thereafter Seth was born on January 13, 1824, in Parkman, Ohio, the eldest of five siblings. His two younger brothers Alfred and Edwin soon followed. The Phelps family moved to Chardon, Ohio and bought a farm just east of Cleveland, a short distance from Lake Erie. Later in life, Seth's father became active in Republican politics in Ohio.[3] Seth grew up near the lake and listened along with his brothers to the stories of his father about his seafaring adventures, especially those of Oliver Hazard Perry. These stories are largely what inspired Seth to pursue a career in the navy.[4] He married Elizabeth Maynadier (born July 21, 1833, died May 27, 1897),[5][lower-alpha 3] on July 1, 1853, whom he would affectionately refer to as "Lizzie". She was the daughter of Captain Maynadier, of the Ordnance Department, Washington D. C. During his naval service Phelps frequently wrote to her of his life in the military.[6][5]

Early naval career

As a boy, inspired by his father's accounts of family history during the American Revolution and the War of 1812, Seth longed to join the Navy. Before going off to join he bid farewell to his mother, who was apprehensive of his joining the navy, and to his proud father, who whole heartily supported Seth's aspirations, and set off for New York, arriving there in January 1842. Here Phelps saw for the first time many tall clipper ships and warships and was impressed with their huge masts and banners filling the skyline. He was assigned to the USS Independence, launched in 1814, a ship of the line, 190 feet long with 74 guns. At the time of Phelps' commission, the vessel had been converted to a 60-gun frigate.[7][8]

Phelps was anxious to go out to sea, but the Independence remained in port for several months. On May 14, 1842, he finally got his first such orders, boarded the Independence and headed for Boston. Phelps found his first day at sea exhilarating; however, as the sea became rougher, the young Phelps had to deal with sea sickness by stomping on the deck while marching from stem to stern. As a midshipman, his visit to Boston marked the end of his probationary period, at which time his captain would decide if Phelps was fit to continue service, and Phelps was approved. When he learned that the USS Columbus needed midshipmen for its service in the Mediterranean, he wanted to transfer. To get past the six months' required service as midshipman for that position, he wrote to Ohio representative Elisha Whittlesey in Washington D.C. for a transfer. Upon Whittlesey's recommendation, at age seventeen, Seth's appointment to midshipman was made on October 24, 1841.[lower-alpha 4] He transferred to Columbus, a ship of the line, and when his orders arrived he served the next three years with the Mediterranean Squadron, considered the choicest of the several active U.S. squadrons stationed about the globe.[9] The Columbus was an old ship that had seen years of duty. When Phelps reported aboard he found the ship's rigging, sails and other fixtures in very poor condition. Before departing from Boston, Phelps and other crew members were given the task of replacing the ship's ropes and sails with new ones. After weeks of repairs, the Columbus finally departed Boston and on August 24, 1842 Phelps was at sea for the first time. While aboard, Midshipmen were required to continue their education, studying mathematics and schooled in the ways of navigation, weapons, along with knot-tying classes, where more than fifty knots, splices, and hitches had to be mastered.[10]

After an uneventful voyage, the Columbus's first call was at Gibraltar. Stopping briefly, she then joined the USS Congress and set sail for Port Mahon in the Balearic Islands, where upon arrival they joined with the rest of the Mediterranean Squadron.[11] That winter, after demonstrating that Phelps was a hard worker he was made Master-Mate of the Main Gun Deck. His promotion was the cause of resentment to a couple of Phelps's shipmates, who sometimes would resort to measures aimed at getting him into trouble, but which never succeeded. Writing to his father, Phelps maintained that there were times when they would attempt to provoke him to a duel, but reassuring his father, he said he abhorred the practice and always managed to avert the situation.[11]

After a foiled smuggling attempt in Havana aboard the Robert Wilson, custody of the ship was given to the Americans. Phelps volunteered to help get the ship back home and was made midshipman. With the former crew under arrest, the ship departed on February 1, 1846, headed for Portsmouth, Virginia. Later he removed to Washington, D.C., where he lived for a brief period.[12]

In June 1846 Phelps received his long-awaited orders to attend the naval school at Annapolis, Maryland. He was to report aboard the Bonita. In a June 15 letter to his father, he expressed his regrets that he could not visit with family, who were only 30 miles away D.C.[13]

Mexican war

Phelps served aboard the Bonita and Jamestown during the Mexican–American War, giving naval support to Winfield Scott's Army during the Siege of Veracruz. Much of his time was also spent patrolling the Mexican coast on blockade duty. In little time Phelps had already developed strong opinions about how the war should be conducted, and was displeased that the Navy was lending much of their service protecting merchant ships while sailors were coming down with scurvy for want of provisions.[14]

In 1857, after ten years of shore duty, Phelps was assigned to the USS Susquehanna, a side-wheel man-of-war and returned to serving at sea in the Mediterranean Squadron.[15]

Service in the Civil War

Seth L. Phelps played a major role in the many naval operations in the Western Theater of the Civil War, and commanded various gunboats that were part of the Mississippi River Squadron which were active on the Mississippi, Ohio, Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. Created on May 16, 1861, it was controlled by the Union Army until September 30, 1862. John Rodgers was the first commander of the squadron and was responsible for the construction and organization of the fleet. He obtained the service of three experienced men, Phelps, Strembel and Bishop to assist him with the huge task of converting riverboats into gunboats.[16] Foote encouraged Major General Henry W. Halleck and General Ulysses S. Grant, to move against key positions held by the Confederates on the several rivers that controlled vital river access to the south. During this time Phelps worked closely with Admiral Foote and General Grant in the various battles that opened up the South to the Union Army and Navy. When Foote assumed command of the squadron it consisted of three timberclad (wooden) vessels, that had been converted to gun-boats by Commander Rodgers, nine iron-clad gun-boats and thirty-eight mortar-boats, some of which were still being built.[17][18]

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Phelps was a Lieutenant and was given command of a small fleet of three vessels: The USS Conestoga, USS Tyler and USS Lexington. Before their commissioning he was disappointed to find the ships in dire need of repairs and that they were grounded in shallow water on the Ohio River. None of the vessels had any armament aboard yet and were in need of other equipment. Phelps had to board the Conerstoga, the smallest of the three vessels, through a gun-port, as there was no gangplank available at the time. He was greeted by Captain S. L. Shirley, who was the president of the Louisville & Cincinnati Mail Boat Line. On June 30 Phelps hired three dredge boats and attempted to clear a deep enough passage to free up the vessels, but during the summer months the Ohio River became increasingly shallow, preventing the operations to free the vessels. In the meantime Phelps wrote to Commander John Rodgers of the situation. Rodgers was working with General Grant to coordinate naval operations with those of the Union Army in the Western theater.[19] In the meantime, having to wait several weeks for the river to rise, Phelps proceeded with repairs and the conversion of the vessels into gunboats.[20] After repeated efforts to get the vessels down river, Rodgers arrived at Cairo, Illinois where the vessels underwent further fitting out.[21] He had managed to enlist three naval lieutenants to commanders the individual vessels along with some 1000 fishermen from the east coast, but was still short of the manpower needed to effectively use the vessels in combat.[22] Phelps was finally given command of the converted gunboats, with orders to proceed to Fort Henry, under the command of Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman, on the Tennessee River and assist General Ulysses S. Grant in the eventual siege and capture of two riverfront forts he proved instrumental in the ensuing Union victory at the Battle of Fort Henry and Battle of Fort Donelson during the spring of 1862.[23] Having much experience navigating and scouting the Ohio, Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, Phelps was considered the most knowledgeable about running gunboats along these rivers.[24]

Foote relieves Rodgers

Rear Admiral

Foote, commander at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, was promoted to Captain in July 1861 and in August was ordered to take command of the Western Rivers Fleet. On September 5 he reported to General Frémont, and by September 9 arrived in Cairo to relieve Commander Rodgers.[25] After internal conflicts between Admiral Rodgers and General John Fremont, the Navy Secretary, Gideon Wells, ordered Rodgers to relinquish command of the squadron to Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote,[26] who assumed command of the squadron on September 6, 1861.[27] Foote invited him to remain on, but Rodgers, eager to get back to sea duty, declined, requesting instead a transfer to the Atlantic fleet.[28] By this time warfare on the rivers had already commenced. On September 4 a Confederate gunboat CSS Jackson had already fired on timberclads USS Tyler and USS Lexington while they were performing reconnaissance on the Mississippi River below Cairo. Along with the Conestoga these vessels had escorted General Grant's transports to Paducah and on the 10th were sent down to give support to Union troop movement from Norfolk, Missouri. Phelps, commanding the Conestoga, wrote of the account in his report to Captain Foote. Four days after Foote arrived in Cairo he received orders from Frémont to proceed with the fleet's mission on the Mississippi.[29]

River reconnaissance

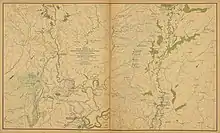

Before Phelps arrived it was uncertain as to the garrison strength of Fort Henry and the disposition of its defensive earthworks. Before Phelps's reconnaissance efforts, the existence of Fort Donelson was not known. Phelps was originally active with the Conestoga on the Ohio River working with General Charles F. Smith above Paducah, Kentucky.[30] At the request of General Smith, Phelps began making reconnaissance missions on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, when autumn water levels allowed it. On October 11, 1861, Phelps, aboard the Conestoga, ascended the Tennessee River, and as the vessel approached Fort Henry the Confederates fired signal rockets into the sky, warning of its arrival. Phelps subsequently stopped and anchored for the night. The following morning he approached closer and anchored. With a spyglass he began studying the fort, noting that it was armed with heavy guns. Phelps ordered shore parties to venture further upstream where they discovered that the Confederates were busy converting steamers into gunboats, including the Eastman, later considered to be the fastest steamer in the Western theater.[31]

The next morning, after completing his mission on the Tennessee River, Phelps ascended the Cumberland River for sixty miles to investigate reports of a fort (Donelson) being built above the town of Eddyville. Upon discovering that Confederate cavalry were harassing Unionists in town, he gave a stern warning to the townspeople to desist, or that he would return with force. Keeping his word, he returned twelve days later, on October 26, with three regiments from the Ninth Regiment of Illinois Volunteers, commanded by Major Jesse Phillips, all on board the Lake Erie No.2.[32] In his report of October 28, Phelps reported to Foote that the Confederates had a system of communication between Eddyville and Smithland which employed the use of runners. Phelps reported, that under cover of darkness he slowly maneuvered his vessel to a point on the river near the town of Eddyville, where Phillips' companies disembarked, marched seven miles inland, and discovered a rebel encampment; Philips' Union volunteers commenced firing upon the Confederates and then charged with bayonets, scattering the rebels in retreat. Phelps reported that in the meantime he deployed a line of picket-guards around the town to prevent any escape of messengers leaving with dispatches of warning, and to prevent any refugees from the rebel camp coming there to hide. After the battle there were only four Union volunteers wounded, with some horses perishing during the battle. Captured were twenty-four prisoners, seven negroes,[lower-alpha 5] two transport wagons, thirty-four horses, and a flatboat upon which the prisoners were transported. An assortment of other supplies were also seized. Phelps closed his report to Foote with praise and respect for Major Phillips and his volunteers.[33]

Foote was enthusiastic about the prospect of using gunboats for reconnaissance, and promptly made preparations in January 1863 to further navigate the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. The idea of using gunboats for river reconnaissance was before this time a novel idea whose tactics were not thoroughly tested, and it was important to make careful reconnaissance trips, without arousing any suspicion of what was being planned. It was also uncertain how ironclads would fare against land-batteries at close range. Another of these expeditions was conducted on January 7, which was logged and reported by Lieutenant Phelps of the Conestoga.[34]

Yesterday I ascended the Tennessee River to the state line, returning in the night. The water was barely sufficient to float this boat, drawing five feet four inches, and in coming down we dragged heavily in places. The Cumberland is also too low above Eddyville. The rebels are industriously perfecting their means of defense both at Dover and Fort Henry. At Fort Donelson (near Dover) they have placed obstructions in the river, one and a half miles below their battery on the left bank ...

— S.L. Phelps[34]

Fort Henry

By the end of January, Foote and Phelps, through their persistent reconnaissance efforts, had determined that Fort Henry mounted a small number of heavy guns and had a garrison of 1700–1800 men. Having heard that the Confederates were building ironclads up river, he had hoped to proceed further, but the presence of the fort's heavy guns prevented the move.[35]

General Grant with two divisions took up positions about the fort on February 4–5. Foote and Phelps arrived with their gunboats on February 6. Phelps' three timberclad gunboats were vulnerable to cannon fire and took up positions some distance behind Foote's ironclads for protection and began their bombardment of Fort Henry from long range. One of Foote's ships, the Essex took a direct hit to the boiler, which exploded, killing and wounding thirty-two crewmen.[36][lower-alpha 6] After about 75 minutes of bombardment, Tilghman finally struck the fort's flag and surrendered.[36][37][38][39] Soon a gunboat with the adjutant-general and a captain came alongside reporting that General Tilghma wished to communicate with the flag-officer. Foote dispatched Commanders Phelps and Roger N. Stembel with orders to hoist the American flag over the fort where the Confederate flag had previously been flying, and to inform General Tilghman that Foote would see him on board his flag-ship.[40][36][41]

For his daring role in the capture of Fort Henry, Phelps subsequently received much praise in the northern press. The New York Times exclaimed, "Never has a more gallant officer trod a plank". Praise from The Cincinnati Gazette went even further: "The selection of Captain Phelps for this important expedition has proven one of the best that could have been made. …"[42] After the fall of Fort Henry, Foote, by order of General Grant,[lower-alpha 7] in turn ordered Phelps to proceed upriver with his fleet of timberclads and capture the strategically important Memphis & Charleston Railroad bridge.[lower-alpha 8] Here Phelps discovered the fleeing Confederates had obstructed the 1,200-foot-long trestle. The bridge connected General Polk's army in Columbus and General Johnston's army in Bowling Green. However, the Union needed this bridge intact, so Phelps landed a party and began making repairs, which took no more than an hour. After receiving follow-up orders, however, Phelps had a small section of the bridge burned and destroyed some of the rails to prevent the Confederates from using it after they departed. Before leaving Phelps' crews had captured supplies that were headed for Fort Henry.[43]

During the aftermath of the capture of Fort Henry, Phelps continued upriver to a landing at Cerro Gordon where the Confederates were in the process of building and completing an ironclad gunboat, Eastport.[lower-alpha 9] The fleeing Confederates had no time to effectively scuttle the ship, and Phelps' crews quickly went ashore and saved the vessel, 280 feet long and in excellent condition, and capturing a large quantity of ship's lumber and other material used for the completion of the vessel.[44] Phelps reported that her engines were in flrst-rate order and the boilers, not yet installed, had been dropped into the hold.[45] Phelps had Captain William Gwin and the Tyler remain, the slowest of the gunboats, to guard the captured gunboat, while his crew cut telegraph lines and tore up track. Phelps proceeded to pursue fleeing Confederate transports with his other two gunboats, Conestoga and Lexington, while also engaging in a search and destroy mission, and creating havoc at every opportunity along the way.[46][47] After five hours the faster Conestoga left the Lexington behind and closed in on Confederate Captain Sam Orr, who was forced to set his vessel, containing guns and ammunition, on fire. Phelps ordered his gunboat to remain a safe distance from the blazing vessel, which soon exploded and was completely destroyed.[47] Phelps continued on and soon spotted and overcame two more Confederate gunboats, the Appleton Belle and Lynn Boyd. Their captains realizing they would soon be captured, landed their craft in front of the home of Judge Creavatt, a Union sympathizer, and set them ablaze. Phelps again remained at a safe distance, but when the Confederate vessel, loaded with 1000 pounds of gunpowder, exploded, it shattered the skylights of the Conestoga and caused other minor damage, while the judge's home was shattered from the nearby explosion. Phelps' three timberclads finally arrived at Cerro Gordo by 7 p.m., eight miles downstream from Savannah, Tennessee, where it was greeted by Confederate small arms gunfire from the shores. Phelps ordered the return of fire and turned about.[48]

Phelps finally set out to return to Cairo, passing Commander Henry Walke and the USS Carondelet[lower-alpha 10] who had been ordered by General Grant to wait for Phelps' gunboats and then together proceed towards Fort Donelson. However, when Walke ordered Phelps to proceed to the next fort with him, Phelps refused, having already received a message to rendezvous with Commander Foote at Cario. Walke felt that Phelps refusal amounted to "insubordination" but Foote never said anything about the disagreement.[50]

Fort Donelson

_(14576157349).jpg.webp)

With the fall of Fort Henry General Grant was now preparing to move overland and capture Fort Donelson, approximately twelve miles to the east on the Cumberland River. Foote at this time insisted on returning to Cairo for badly needed repairs on his gunboats. After learning that only the Carondelet would lend naval support to his Army he urged General Halleck to have Foote promptly send more ironclads. Needing more time, Foote, however, relented and transferred men from the damaged gunboats to become part of another flotilla. On February 12, the gunboats Saint Louis, Pittsburg and Louisville passed the Conestoga and Lexington on their way to Cairo for repairs. Foote hailed the vessels and ordered Phelps to turn around and join his flotilla. The badly damaged Lexington, however, continued on, while Phelps, aboard the Conestoga, joined forces with Foote and together proceeded up the Ohio River.[51]

Upon reaching Paducah, Kentucky the combined flotilla was joined by twelve troop transports. Later that afternoon the flotilla departed Paducah, with the Conestoga towing a barge filled with coal, followed by the ironclads. On their way up the Cumberland River the trip thus far was uneventful. About thirty-five miles below Fort Donelson the flotilla came upon the tug Alps, which had been used to tow Walke and his Carondelet to Fort Donelson who had proceeded alone after being rebuffed by Phelps earlier that day.[51]

Grant was unaware of the strength at Fort Donelson when his army approached the fort, and were overconfident and jubilant from their easy victory at Fort Henry, singing songs as they marched. Grant, McClernand and Smith positioned their divisions around the fort. The next day McClernand and Smith launched probing attacks on what they figured were weak spots in the Confederate line, only to retreat with heavy losses. That night freezing weather set in. The next day, Saint Valentine's Day, Foote's gunboats arrived and began bombarding the fort, but were driven back by the heavy guns at the fort. Foote himself was wounded. At that point the battle was proving victorious for the Confederates, but soon Union reinforcements arrived, giving Grant a total force of over 40,000 men. When Foote regained control of the river, Grant resumed his attack, but a standoff still remained. That evening Confederate commander Floyd called a council of war, unsure of his next course of action. Unable to travel due to his wounds, Foote sent Grant a dispatch requesting that they meet. Grant mounted a horse and rode seven miles over freezing roads and trenches, first reaching Smith's division, instructing him to prepare for the next assault. Continuing on he met up with McClernand and Wallace and exchanged reports with the same orders to be ready for battle. Riding on, he finally met up with Foote. After they conferred, Foote and Phelps prepared to resume the bombardment.[52][53]

As the Carondelet closed in within firing range it opened fire on the fort, signaling Grant and the other generals to commence their attacks. After firing ten shells at the fort it withdrew down river. The next day Walke received orders from Grant to resume firing on the fort. Soon after the Carondelet took a hit, causing considerable damage and wounding a dozen men where it withdrew and transferred his men to the Alps and began repairs on his vessel. After repairs were made, the Carondelet resumed its attack on the fort until dusk. When news of the bombardment on the fort reached Foote he was angry that the siege had already begun, as it was his understanding that Grant was going to wait for the arrival of his flotilla. in preparation for the battle Foote ordered Phelps to inspect the Pittsburg and the Carondelet, at which time he appointed him acting fleet captain for the day.[51]

Mississippi River campaign

Phelps commanded the Eastport during the Mississippi River campaigns. Eastport sailed from Cairo, Illinois, in late in August after being repaired and converted for duty on the Mississippi River between Island No. 10 and the mouth of the White River in Arkansas. She was back at Cairo, Illinois, for repairs when, on 1 October 1862, the Eastport and the other vessels of the Western Flotilla were turned over to the Navy and became part of the Mississippi Squadron.

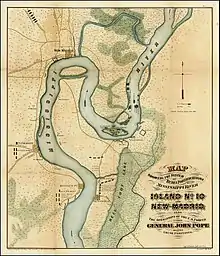

Island Number Ten

On the April 23, Foote made a reconnaissance of Columbus and saw no outward signs that the Confederates were abandoning their position. Foote sent Phelps to the post with a flag of truce and discovered that the Confederates were in the process of abandoning the location, and were moving most of their heavy guns to Island No. 10. Columbus was occupied by Union forces, on March 4.[54]

Shortly after the Confederate Army abandoned their position at Columbus, Kentucky and had fallen back to positions at New Madrid and Island No. 10. The Union Army of the Mississippi under Brigadier General John Pope, made the first probes, coming overland through Missouri and occupying the town of Point Pleasant, Missouri. After countermanding orders and delays from Halleck, Foote and Phelps, for purposes of giving naval support to Pope, departed Cairo down the Mississippi River, on March 11, with a flotilla of five gunboats,[55][56] which included the USS Benton, commanded by Captain Phelps, USS Louisville, Benjamin M. Dove, USS Carondelet, Commodore Henry Walke, Conestoga, George Blodgett, and the USS Cincinnati, commanded by Roger Stembel.[57]

On March 14, the flotilla continued its descent arriving at Hickman, Kentucky at 5 P.M., some twenty-five miles below Columbus, where Foote decided to anchor for the night.[58][57] On the morning of March 15, the flotilla continued on. Foote,[lower-alpha 11] and Phelps arrived aboard the Benton and encountered the Confederate steamer CSS Grampus which unexpectedly appeared through the fog. Alarmed, Grumpus stopped its engines and struck its colors, but her commander then quickly changed his mind, turned about and headed downriver, with Benton firing shells that fell short of her stern. Moving on they spotted a chain of batteries of at least 50 heavy guns, which extended four miles along the crescent-shaped Tennessee shore, thwarting any further passage. The Benton continued slowly while Phelps discerned the trees along the bank for possible hiding places for shore batteries, sometimes firing into suspected areas. Upon discovering no hidden guns, the Benton stopped at the double bend in the river, where several other vessels were docked, along with a floating shore battery. After determining that there were no Confederates about, a tug was dispatched to place and tie up mortar boats. At 1 o'clock in the afternoon, the mortar boats commenced firing upon the island, with the Benton joining the bombardment two hours later. Red Rover and other Confederate vessels moved out in retreat. With Confederate guns silent, Phelps boarded a tugboat and took it downstream, turning into and out of range of Confederate batteries, hoping to draw their fire and revealing their strength. With no response from the Confederates, Phelps returned upstream to the Benton, where he spent the remainder of the afternoon firing shells at nearby Forts Thompson and Bankhead.[60]

General Pope advanced on New Madrid, an engagement that lasted from February 28 to March 14, with very few casualties,[61] and proceeded on to Point Pleasant, Missouri and using his guns to established a blockade of the river. To reach Island No. 10 he would need gunboat support from Foote and Phelps to suppress Confederate batteries on the adjacent Tennessee shore. Phelps in a March 27 report to Whittlesey wrote, "The rebels have an immensely strong position here, and the gunboats cannot get at them. ... The rebels have selected this place with this knowledge and we cannot get troops to where they are except from below..."[62]

The morning of March 15 was cold and rainy with high winds. As Phelps and the Benton proceeded down the river it sighted the Confederate scout CSS Grampus which came about in front of the Benton, stopped and struck her colors. Then after giving four long blasts on her whistle, she quickly retreated, while the Benton fired four shots, all falling short of the target. At 8 P.M. Phelps and his flotilla approached Phillip's point, with island No. 10 sighted in the distance.[63] On March 17, Foote called his commanders together in council to discuss the next best course of action.[64]

A plan was devised to cut out a channel north of Island no. 10. allowing union vessels to bypass Confederate batteries on the island.[65][66] After days of bombardment from Union gunboats and floating batteries, Pope was finally able to move his army across the river and trap the Confederates opposite the island, who by now were in retreat. Outnumbered at least three to one, the Confederates realized their situation was hopeless and decided to surrender. At about the same time, the garrison on the island surrendered to Flag Officer Foote and the Union flotilla. As Foote and Phelps were looking on from the Benton a Confederate steamer DeSoto approached with a flag of truce with lieutenants George S. Martin and E. S. McDowell aboard with a message. After the meeting Phelps escorted the Confederate officers back to the island, returning April 8 to announce their unconditional surrender.[64]

Foote stands down

As Admiral Foote's wounded foot became swollen his overall conditioned worsened, making it extremely difficult for him to make his way about the ship, Captain Phelps was assuming more and more of the everyday responsibilities of running the flotilla. Foote summoned three surgeons to examine his condition, where they found that bones were broken and recommended that he be permitted to return home on a leave of absence. Foote forwarded their recommendation to Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles with the request that temporary command be given to Captain Charles Davis, as Acting Flag Officer. Foote had considered giving the young Phelps the command, maintaining that "Although Lieutenant-Commanding Phelps, the flag captain, is qualified to command any squadron...", the Navy was bound by a system of seniority.[67][68] Despite Phelps's proven ability he was deemed too young to assume command without inciting the resentment of other officers who had seniority,[68] which, regardless, invoked the ire of Phelps. Knowing there were other officers on the list for promotion, many of whom had left the Navy five to ten years ago, but who would nonetheless be placed ahead of him on the promotion list, Phelps wrote to his influential friends in Washington requesting that a bill be enacted for purposes of allowing the most qualified officers to assume the various commands, regardless of any seniority. Since the growing Union Navy was in desperate need of experienced officers, Phelps's request, though compelling, was declined by the Senate fearing that it would counter efforts to invite former officers back into the Navy.[69] Temporary command of the flotilla was eventually given to Davis on May 9.[68]

Days passed, and on May 8, Admiral Foote, now unable to move about on his own, and who had confined himself to his sleeping quarters, finally stepped down from service. Before his departure all the crews from the squadron assembled for Foote's farewell. As he slowly emerged on deck he was greeted by cheers and hurrahs. In an emotional departure, Foote expressed his respect and gave praise to all who had served under him. At 3 P.M, the USS Desoto came alongside the Benton, and with the help of Phelps and another officer, Foote boarded the accompanying ship, and on May 9,[70] departed. With Foote relieved of command, Admiral Davis became the new flag officer of the Mississippi River Squadron.[71] After Foote had left the squadron, Phelps kept him informed of the state of affairs with frequent reports.[72]

Fort Pillow

Having tended to repairs and resupply, the Union fleet proceeded south to a position a few miles upriver from Fort Pillow, the last Confederate stronghold protecting Memphis fifty miles to the south. The fort was protected by high bluffs, miles of trenches and numerous batteries mounting heavy guns. On April 12, the CSS General Sterling Price, a Confederate ram and gunboat mounting two guns and part of the Confederate River Defense Fleet,[lower-alpha 12] arrived at the scene, pursuing a Union transport, but when it came close to other Union gunboats, the Confederate ram abruptly withdrew, not knowing Union fleet strength due to darkness. The next morning the Price joined forces with several other rams and forming a line, approached the Union fleet within a couple miles. The Benton, with Foote and Phelps aboard, opened fire, with Confederate gunboat CSS Maurepas returning fire, with shots from both gunboats falling short of their targets.[74]

The flotilla settled into its normal routine and while the days went by only routine bombardments at Fort Pillow were conducted. Running the Confederate batteries with their numerous heavy guns was ruled out. On April 28, a number of Confederate deserters made their way to the Union gunboats, all sharing the same news that an attack on Union gunboats was going to occur that evening as soon as a new Confederate gunboat arrived. Foote then ordered preparations for a night time engagement. When darkness fell, Phelps ordered the Benton to take up a position further downstream, hoping to surprise and intercept any approaching Confederate gunboats under cover of darkness, but no enemy gunboats came along.[75][70]

The day after Foote's departure, the Cincinnati positioned Mortar boat No. 16,[lower-alpha 13] and then docked alongside. The mortar boat opened fire at 5 a.m. By 6 a.m. eight Confederate rams rapidly steamed upriver, coming around Graighead Point, with black smoke revealing the advancing fleet in the distance. Union crews "beat to quarters",[lower-alpha 14] with Union gunboats taking positions out into the river. As they closed on the Union vessels at Plum Point Phelps ordered firing from the Benton and the Cincinnati. After approximately an hour long sortie the Confederate gunboats retreated. He at that point determined that the appearance of the Confederate gunboats, who retreated with no damage, were sent to scout out Union positions and strength. Phelps' attitude was such that he exclaimed, "The more they see us, the better. They won't like us any more for what they witness. They are welcome to all they can discover".[76][77]

On May 10, 1862, the Confederate River Defense Fleet early in the morning emerged from around Craighead point, surprised and attacked the Union squadron that had moved up to support mortar boat attacks on Fort Pillow. With the General Bragg, commanded by Captain W.H.H. Leonard, leading the Confederate rams at full speed, they born down on the Cincinnati. Phelps, aboard the Benton had spotted their smoke from the distance and attempted to signal the other ships, but morning fog obscured their warning signal and went unnoticed. During the battle, the Union's Cincinnati and Mound City were rammed. The two badly damaged vessels retreated to shallow water near the riverbank and sank. Other ships began entering the fray including USS Mound City and CSS Van Dorn which rammed Mound City. In the morning fog and smoke from numerous broadsides from the gunboats, visibility was greatly impaired and a general state of confusion prevailed over the battle. Following the Carondelet Phelps arrived in the slow-moving and massive Benton swung about and opened fire. He then brought the Benton around and came alongside the sunken Cincinnati with her crew waiting on top of the wheelhouse. Unable to pursue due to deeper draft, the Confederate ships then withdrew. Although the Confederates were victorious, the Union squadron was able to proceed down river and attack the Confederate squadron during the Battle of Memphis the following month. At a later date both the Cincinnati and Mound City were raised and placed back into service.[78]

After the Cincinnati and Mound City were rammed, it prompted Phelps to devise defensive structures for the various Union gunboats. In a May 28 report to Foote, who was recovering in Cleveland, Phelps informed him that he had reinforced the Benton and the other vessels by placing railroad iron along the bows and sterns, by slinging logs about the sides, and by placing protective iron framework around the rudders, along with devising other structural enhancements for the vessels. Reporting to Foote, he stated that Colonel Alfred Ellet had also arrived with some half dozen rams. While Phelps related that his report was made in the midst of much confusion, he also intimated that he was pleased with the performance of Davis, the new fleet commander.[79][80] There was but little cooperation between Ellet and Davis – his rams viewed by the regular navy as inadequate for combat. Both Phelps and Davis expressed this view in their later writings.[81]

With the Confederate fleet in retreat, laying siege on the fort was Davis's next objective. However, when an indifferent Ellet learned that Davis intended to attack the fort he steamed by the slow-moving ironclads with his fleet of rams before Davis could launch reach and attack the fort. Upon approaching the fort Ellet heard gunfire and saw smoking billowing up from the earthworks. He went ashore with a squad of men and discovered that the Confederates had evacuated the fort and disabled or destroyed everything of use to the Union. Later that day Phelps was inspecting the inside of the abandoned fort and discovered that the Union fleet could have safely passed the fort by staying close to the river bank below the steep buffs, out of the line of fire from the fort's guns, realizing that Davis had wasted an entire month.[82]

Memphis

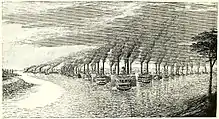

The First Battle of Memphis was a naval battle fought on the Mississippi River just above Memphis on June 6, 1862, resulting in a major defeat for the Confederacy, and marked the virtual elimination of the long-standing Confederate naval presence on the river. Shortly after securing Fort Pillow, the Union fleet made way for Memphis on June 5, leaving the Pittsburg at Fort Pillow to lend any needed support for the Union garrison, while the Mound City stood by to escort any transports that would arrive. At 2 p.m. Fort Randolph was sighted in the distance. Greeted by Captain Dryden of the Monarch, they were informed that the Union had taken the fort and that the "stars and stripes" were flying overhead. Phelps, standing on the deck of the Benton observed the fort through his spyglass and confirmed Dryden's claim.[84]

Shortly after 4 p.m. just above island No. 37, Phelps encountered the Sovereign[lower-alpha 16] and fired a warning shot for her to come about, which was ignored as the Confederate vessel turned about and began retreating. Davis ordered Phelps to fire again. The Carondelet and the Cairo also joined in and fired. As the Sovereign disappeared around a bend Davis ordered Lieutenant bishop to pursue the vessel in the faster moving Spitfire with its 12-pound Howitzer bow gun. The Spitfire soon overcame the enemy vessel and began firing, causing the crew to run their boat ashore. In their haste they attempted to destroy the boilers, but the attempt was averted. Meanwhile, the remainder of the union fleet stretched back for ten miles and slowly made their way, reaching a group of small islands just north of Memphis. Phelps asked if it was safe to anchor at this point, and upon confirmation the fleet began to anchor in a line of battle formation.[85]

Confederate commander James Montgomery's River Defense Fleet moved up the river to engage the union fleet unaware of the presence of the combined fleet, which this time included Ellet's squadron of rams. The battle started with an exchange of gunfire at long range, the federal gunboats setting up a line of battle across the river and firing their rear guns at the cottonclads coming up to meet them. The USS Queen of the West, then quickly steamed forward between the slow-moving ironclads and initiated the battle by ramming the CSS Colonel Lovell, almost cutting the vessel in two.[86] Before breaking free from the Lowell she was rammed by the Sumter[lower-alpha 17] Due to the lack of organization on both sides the battle was soon reduced to a melee. During the engagement Ellet was wounded in the knee from a pistol shot.[lower-alpha 18][87]

Phelps aboard the Benton fired on the CSS General Thompson causing the vessel to explode. The Beauregard[lower-alpha 19] and the Little Rebel were struck in the boilers and disabled. The Rebel was pushed aground by the Monarch and captured. Only the CSS General Van Dorn was fast enough to get away.[89]

By 7:30 a.m., the entire Confederate Defense Fleet had been destroyed, as the converted steamboats proved no match for the powerful Federal ironclads and rams, resulting in the immediate surrender of the city of Memphis to Union forces within a few hours. The Benton dropped anchor and sent her gig to retrieve a well-dressed man standing near the shore waving a white flag. Phelps brought the man aboard to see commander Flag Officer Davis for a conference. After their meeting, Phelps accompanied the man back and proceeded into town with an official request for surrender, and was met with jeers from some of the crowd, but without further incident. Phelps handed the notice to Mayor John Park, who replied: "Your note of this date is received and the contents noted. on reply, I have only to say, that as the city authorities have no means of defense, by the force of circumstances the city is in your hands."[90][91] Phelps was promoted to Lieutenant Commander in July 1862. [92]

Vicksburg Campaign

Flag Officer

In the months before the Vicksburg campaign, before the actual fighting on land began, there was much naval activity occurring on the Mississippi near Vicksburg between Union and Confederate gunboats. During this time Phelps served aboard the Benton, most notably with his engagement of the Confederate steamer Fairplay, being used as a transport to move military supplies into Vicksburg.[93] In August 1862 an expedition was sent down the river composed of the Benton, Mound City, and Bragg, together with four of Ellet's rams, the Switzerland, Monarch, Samson, and Lioness, all under the command of Phelps, with a detachment of troops under Colonel Charles R. Woods. Thirty miles above Vicksburg, at Milliken's Bend, the Confederate transport steamer Fairplay, having made its second run across the Mississippi from Vicksburg, was captured, loaded with a heavy cargo of arms and ammunition which included twelve hundred new Enfield rifle-muskets and four thousand new muskets, along with a huge amount of small arms and artillery on its way to Confederate General Theophilus Holmes, the new commander of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department. Phelps and his boarding party from the Benton took the crew of Fairplay completely by surprise. The capture of this vessel and its payload of supplies, in effect, removed a division of rebel troops without the loss of one Union soldier.[94]

The gun-boats then penetrated far up the Yazoo River, and two of the rams even ascended the Sunflower River for twenty miles. When the expedition returned to Helena, it had destroyed or captured a vast quantity of Confederate military supplies.[93]

Flag Officer Davis had not shown the initiative that the Navy Department wanted, thus Commander Porter became Acting Rear Admiral and assigned to command the Mississippi River Squadron, arriving in Cairo, Illinois on October 15, 1862.[95] Phelps had wanted the command but was concerned that his younger age would be an obstacle. He wrote to Foote, Whittlesey and others of the possibility, citing his time and diverse experience over others. He maintained that two senior officers were about to retire from the Navy, another was in ill health and two others had already been passed over for promotion. In his effort Phelps solicited influential senators such as Benjamin Wade of Ohio and James Grimes of Iowa along with governors David Tod of Ohio and Oliver Morton of Indiana. Former flag officer Foote was supportive of his effort but cautioned Phelps that the prospect was a sensitive one. Phelps subsequently left the matter in the hands of those in Washington and returned to the flotilla, turning over command of the Benton to William Gwin.[96] By this time the Eastport had undergone changes to her hull, engines and interior infrastructure and had been converted to a ram. The vessel was now considered the finest gunboat in the union's service.[97]

After Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut accepted the surrender of New Orleans, and later taking Baton Rouge and Natchez, he ascended the Mississippi River with a fleet of eight ships and made his way past the Confederate batteries at Vicksburg on the east bank of the Mississippi River. Shortly thereafter Farragut dispatched a request to General Davis in Memphis to join him. Accepting the request Davis had Porter assemble what gunboats he could spare. Porter departed Memphis on June 29, 1863, arriving to join Farragut's fleet just above Vicksburg on Tuesday morning, July 1. With him was Phelps, aboard the Benton, with the Cairo and Louisville, along with six mortar boats. Writing to Whittlesey a week later, Phelps observed that "The vessels of this lower fleet are very beautiful as contrasted with our strange looking rivercraft; yet not one of them would have floated five minutes in the fire concentrated on four of our queer crafts at (Fort) Donelson". Phelps also observed the attitude of Farragut's crews towards the riverboats; Still reporting to Foote, he noted that when Farragut's crews, some of whom were old friends who had themselves served aboard riverboats, were reminded of the firepower the riverboats could withstand and the battles they've endured, their attitudes changed.[98] Phelps was not particularly fond of Farragut, describing him as a rash and impulsive man who felt that he must always keep busy for fear of being accused of "doing nothing", and who often "acts without purpose or a plan" based or common sense.[99]

On May 19 Grant had launched a major assault on land along a three-mile front but was repulsed. A second attempt was made on May 22 where some 220 field-pieces along with Porter's heavy guns from his fleet of ironclads launched the biggest artillery assault thus far during the war. A few hours later all three of Grant's corps pushed forward but were again met with heavy resistance, suffering heavy losses from Lieutenant General Pemberton's troops. Grant then realized Vicksburg could not be taken by storm, so resolved to take Vicksburg by siege while reinforcements poured in from Memphis, swelling his troop strength to over 80,000.[100]

On the 4th of July, Vicksburg surrendered which was followed by the fall of Port Hudson on the 9th. Farragut then reported to Porter, whose vessels were especially fitted for the waters of the Mississippi, and relinquished to him command of the Mississippi Valley above New Orleans.[101]

Red River campaign

Phelps was active in the Red River Campaign, involving a series of battles fought along the Red River in Louisiana from March 10 to May 22, 1864, with the objective of advancing to and occupying the Confederate stronghold at Shreveport, Louisiana, where General Kirby Smith and his force of over 20,000 men were deployed.[102]

After the fall of Vicksburg, the Mississippi River from Cairo to the Gulf of Mexico was finally in control of the Union. As northern Louisiana, southern Arkansas and eastern Texas, with their vast cotton fields, were still an economic objective, controlling it would not only put millions into the U.S. Treasury, but also deprive the Confederacy of badly needed wartime funds that cotton, with its inflated value, would bring.[103]

General Sherman had approached Rear Admiral David Porter with the idea of a naval expedition to Shreveport by way of the Red River. The river was low for that time of year, and Porter doubted the probability of the mission's success. Sherman, however, was anxious to proceed with the expedition as he had promised he be in Natchez by late February 1864. Porter didn't like the idea of taking his fleet past Alexandria but acquiesced and assigned the most formidable ships of the Mississippi Squadron to meet the task, which included the huge Eastport, commanded by Seth Phelps.[lower-alpha 20][104] The fleet up to this point was the largest yet assembled in North America.[105]

Union Generals Nathaniel Banks and A. J. Smith, along with gunboat squadrons under the command of Admiral Porter were to meet at Alexandria, on March 17 and make their way up the Red River some 350 miles to Shreveport. (Porter had replaced Davis as commander of the Mississippi Squadron in October 1862, becoming Acting Rear Admiral.[106]) Of major concern to Porter for his squadron of gunboats was the shallow depth of the river with its many narrow bends, which would soon prove to be a major impediment for the advancing gunboats.[107][108] During most of the year the river was navigable only by small, shallow draft, vessels, making Porter very reluctant to take his squadron past Alexandria, however, Banks persuaded him by pointing out that if the expedition to Shreveport failed, blame would fall on him. While preparations were being made Phelps was relieved of the Tennessee Division. While everyone was waiting for February's river level to rise, Phelps returned to his home in Chardron to manage its sale, as his parents were not well. In late February he boarded the Silver Cloud assisting General Frederick Steele[lower-alpha 21] who requested his help on the White River buildup for the Red River Campaign. Phelps found himself tending to the various vessels that struck snags and sank and had to be raised. Porter was upset with Phelps for giving in and going along with Steele who he regarded as incompetent for river navigation. After leaving Steele, Phelps arrived at Memphis on February 23, and began getting the Eastport ready for the Red River Campaign.[102]

By March 2, Porter arrived at the mouth of the Red River with his squadron. On the 11th General Smith, with his detachment of ten thousand men from General Sherman's division arrived. The next morning the fleet began its ascent up the river. On March 14, just before reaching Fort deRussy, obstructions in the river were discovered. Porter ordered Phelps to "clear the way!" Phelps, in turn, ordered the Hindman to ram the obstructions and alternately pull them away. Meanwhile, Porter and Smith tried to reach the fort by way of the Atchafalaya River. Porter was subsequently deterred on the Atchafalaya and finally turned around and began the trip back up the Red River.[109][110]

Reaching Fort DeRussy, Porter's gunships began to shell the fort while A. J. Smith 's troops moved in to engage the rebel fort Confederate Major General John Walker, realizing he was up against overwhelming odds, surrendered before the Union assault began. Upon learning that Phelps had already made it to Fort DeRussy, Porter dispatched an order from him to proceed toward Alexandria. Phelps already wanted to get there as soon as possible and sent the faster Fort Hindman and Cricket on ahead, arriving March 15, at the same time Confederate steamers were escaping upriver beyond the falls. Phelps arrived on Eastport a short time later, followed by river monitors. The next morning he was joined by eight other gunboats. Phelps landed a force under Admiral Selfridge to occupy the town and seize any Confederate property. The squadron had now made good its promise to be at Alexandria by March 17, General Banks, however, did not arrive until ten days later. Immediately after the arrival of the fleet Admiral Porter, not waiting for Banks, began efforts to get his squadron of thirteen gunboats upriver beyond the city.[111][112]

Porter remained in Alexandria so command of the squadron at Grand Ecore fell on Phelps. As cotton was a primary objective, Phelps observed that the three barges Porter had intended for use as a bridge were being loaded with cotton gathered by the Army from the surrounding area. Phelps reported the affair to Porter who approved, much to Phelps's disappointment, who was not keen on the cotton speculation that was occurring in the midst of a war. When Porter arrived from Alexandria he found that the Eastport had gotten past the shoals at Grand Ecore but could proceed no further due to the low river level which was rising very slowly. Subsequently, Porter had to proceed with the remainder of his squadron of light-draft tinclads, monitors and transports. On April 7, Porter departed from Grand Ecore with several gunboats and the transports, leaving Phelps behind in command of the heavier vessels.[113][114]

General Banks chose an alternate route in his effort to march to Shreveport and became separated from the protection of the squadron's heavy guns and his supply. When attacked by General Richard Taylor,[lower-alpha 22] resulting in the Battle of Mansfield, Banks, suffering heavy losses, was forced to retreat to Pleasant Hill fifteen miles to the southeast. The next day Banks called a council of war and it was decided that an advance on Shreveport was no longer feasible where the fleet began their retreat down the Red River.[115]

During the return journey, the Eastport, captured by Phelps on an earlier mission, struck a mine on April 15, 1864, but was repaired and refloated. At this time the Red River was getting lower. On the return trip to Alexandria the huge ironclad[lower-alpha 23] had already grounded eight times, and once again had grounded hard near Montgomery. After laboring all night Phelps reluctantly admitted that there was no other alternative but to destroy the prize vessel so it would not fall into the hands of the Confederates.[117][118] Porter and Phelps were in charge of pyrotechnics, placing several tons of gunpowder in barrels about the ship. Phelps lit the match himself, and both men barely made it off the vessel on to the awaiting Hindman in time before the Eastport exploded into pieces, with large sections of the hull falling all around them. The Confederates were nearby and herd the explosion and were upon the scene directly and began firing their rifles and rushed an attempt to board the Cricket which was tied up near by, but were repulsed by canister shot from the Cricket' and other Union gunboats nearby.[119][120]

Later life

After the war, in 1875, General Grant (now President of the United States) nominated Phelps to serve on the temporary Board of Commissioners. When Congress made it official in 1878, Phelps was elected as the permanent Board's first president. He served for one year, resigning on November 29, 1879.[121]

Phelps Vocational School in Northeast DC is named for Phelps.[122] Additionally, his home at 15 Logan Circle in Washington still stands and now houses the Old Korean Legation Museum.[123][124]

In 1883, President Chester A. Arthur appointed Phelps Minister to Peru. He arrived in Lima, Peru in 1883. Early in June 1885 Phelps embarked on a hunting trip into the Andes mountains in Peru and contracted what looked like Oroya fever. He did not let it affect his work, but his condition worsened and while working at his desk he suddenly collapsed and died on June 24. Funeral ceremonies were conducted at the U.S. Legation which was followed by a procession of friends and members of Peru's cabinet and diplomats. His body was interred and soon sent to the United States aboard a mail steamer, City of Iowa, with a U.S. Navy escort aboard. He was buried in Washington at Oak Hill Cemetery. Phelps's epitaph simply reads that he served in the Mexican and Civil Wars, at that he was U.S. Minister in Peru. There are no Naval ships named in his honor to date.[122][125] In 1877 Phelps hired an architect, Thomas Plowman, and builder, Joseph Williams, to construct his retirement mansion located at 1500 13th Street, (also known as Logan Circle) at a cost of 5,500. Not long before his death, Phelps decided to build three large houses near his own home as rental investments.[122]

See also

Notes

- Accounts on month of birth vary: Phelps family history text has the month as June.[1]

- Phelps served under, or with, Admiral John Rodgers, Admiral Andrew H. Foote, General Charles F. Smith, Admiral Charles Henry Davis, General Alfred W. Ellet, Admiral David Dixon Porter, and Admiral David Farragut.

- An account of Phelps family history, published 1899, spells her maiden name as Maynoden

- This was a common practice that was recommended to Phelps, and was considered acceptable.[9]

- 'Negro' was the common term and reference used during this time.

- Among those killed was William D. Porter, son of the famous David Porter of the War of 1812.

- Grant mentions Phelps and this order in his Personal Memoirs, Chapter XXI.

- The railroad and its route through Corinth, Mississippi would later be a significant factor in the weeks leading up to the Battle of Shiloh.

- Eastport was soon converted into a ram for use by the Union Army and saw service on the Mississippi River.

- The Carondelet was a City-class ironclad, one of seven vessels measuring 175 feet with a draft of six feet, which also included the Cairo, Cincinnati, Louisville Mound City, Pittsburg, and the Saint Louis.[49]

- Foote was still suffering from a foot wound that was not healing properly.[59]

- The River Defense Fleet consisted of undisciplined civilian riverboat captains in charge of their own vessels, and not under the command of the Confederate army.[73]

- Commanded by Acting-Master Gregory

- Sailor's jargon for getting to one's battle station. See: Glossary of nautical terms

- Not to be confused with Union Colonel James Montgomery (colonel); Other accounts refer to him as Joseph E. Montgomery.[83]

- Not to be confused with CSS Sovereign

- Not to be confused with CSS Sumter, a blockade runner

- He later died as a result of this wound on his way back to Cairo.[85]

- Commanded by Capt. J. Henry Hart[88]

- The fleet also included the Essex, Benton, Lafayette, Choctaw, Chillicothe, Ozark, Louisville, Carondelet, Pittsburg, Mound City, Osage, Neosho, Quichita, Fort Hindman, Lexington, Cricket, Gazelle, Juliet and Black Hawk (Porter's flagship)

- Not to be confused with Confederate General William Steele

- General Taylor was the son of Zachary Taylor.

- The Eastport was the largest of the ironclads at 280 feet, with six and a half inch armor and eight heavy guns.[116]

References

- Phelps, 1889, p. 1076

- Slagle, 1996, p. 8

- Slagle, 1996, p. 392

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 9–12

- Oakhill Cemetery records

- Phelps family, 1899, vol ii, p. 1076

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 9–10

- U.S. Naval Historical Center, 2002

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 12–13

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 13, 16

- Slagle, 1996, p. 16

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 41–44

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 44–45

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 45–47, -

- Slagle, 1996, p. 81

- Joiner, 2007, p. 23

- Hoppin, 1874, p.157-159

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 151–158

- Cooling, 2003, p. 19

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 117–118

- Gott, 2003, p. 25

- Pratt, 1956, p. 19

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 122–124

- Knight, 2011, p. 84

- Walke, Holtzer (ed), 2011 p.p. 174

- Joiner, 2007, p. 25

- Mahan, 1885, p. 16

- Hoppin, 1874, p. 393

- Patterson, 2010, p. 28

- Anderson, 1964, p. 88

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 135–136

- Slagle, 1996, p. 136

- Hoppin, 1874, pp. 178–179

- Hoppin, 1874, p.191

- Gott, 2003, p.51

- Hoppin, 1874, p.205

- Slagle, 1996, p. 152

- Gott, 2003, pp.92–95

- Cooling, 2003, pp. 14–15

- Slagle, 1996, p. 162

- Patterson, 2010, p. 42

- Slagle, 1996, p. 175

- Gott, 2003, pp.107–108

- Hoppin, 1874, pp. 212–213

- Mahan, 1885, p. 25

- Cooling, 2003, p. 113

- Slagle, 1996, p. 163

- Slagle, 1996, p. 165

- Joiner, 2007, p. 26

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 175–176

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 176–177

- Smith, 2001, pp. 141–164

- Brands, 2012, pp. 164–165

- Mahan, 1885, p. 28

- Slagle, 1996, p. 196

- Sherman, 1890, p. 276

- Daniel & Bock, 1996, p. 72

- Slagle, 1996, p. 195

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 195–196

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 195–197

- Daniel & Bock, 1996, p. 65

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 198, 417

- Daniel & Bock, 1996, p. 73

- Slagle, 1996, p. 200

- Daniel & Bock, 1997, pp. 104–107

- Gilder & Lewis, 1887, pp. 461–462

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 213–214

- McCaul, 2014, p. 93

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 214–216

- Mahan, 1885, p. 43

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 216–218

- Hoppin, 1874, pp. 172–173, 215, 317–318, 332, etc

- Slagle, 1996, p. 211

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 210–211

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 215–216

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 216–217

- Mahan, 1885, pp. 43–45

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 220–221

- Hoppin, 1874, pp. 322–323

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 225

- McCaul, 2014, p. 120

- McCaul, 2014, pp. 127–128

- McCaul, 2014, p. 14

- Slagle, 1996, p. 233

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 233–234

- Scharf, 1887, p. 258

- Scharf, 1887, p.241

- Scharf, 1887, p.259

- Scharf, 1887, p.258

- Slagle, 1996, p. 239

- Scharf, 1887, p.262

- McCaul, 2014, p. 34

- Johnson & Buel, 1888, p. 558

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 283–285, 288

- Anderson, 1964, p. 137

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 289-291

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 291-293, 295

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 249–250

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 253–254

- Smith, 2001, p. 252

- Mahan, 1905, pp. 230, 235

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 345–347

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 343–344

- Porter, 1896, p. 494

- Prushankin, 2005, p. 64

- Hearn, 1996, p. 144

- Slagle, 1996, Chapter Fifteen

- Soley, 1903, pp. 376–377

- Joiner, 2007b, p. 61

- Slagle, 1996, p. 355

- Soley, 1903, pp. 377–378

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 356–357

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 360–361

- Mahan, 1885, p. 195

- Slagle, 1996, pp. 361–362

- Joiner, 2007, p. 93

- Porter, 1896, p. 521

- Mahan, 1883, pp. 198–199

- Mahan, 1883, p. 200

- Porter, 1885, pp. 240–241

- Wash'DC public Library, 2002

- Williams, 2005

- "Ambassador Bahk Sahnghoon visits the Old Korean Legation in Washington DC". Republic of Korea Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2019-01-24. Retrieved 2020-09-14.

-

- Kamen, Al (2012-09-18). "Korea set to reclaim former Logan Circle embassy". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2020-09-14.

- Slagle, 1994, p. 395

Bibliography

- Anderson, Bern (1964). By Sea and by River: The Naval History of the Civil War. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-3068-0367-3.

- Brands, H. W. (2012). The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses S. Grant in War and Peace. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-53241-9.

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin (2003). Forts Henry and Donelson: The Key to the Confederate Heartland. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-5723-3265-2.

- Daniel, Larry J.; Bock, Lynn N. (1996). Island No. 10: Struggle for the Mississippi Valley. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0816-2.

- Gott, Kendall D. (2003). Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry-Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862. Stackpole Books. ISBN 9780811700498.

- Hearn, Chester G. (1996). Admiral David Dixon Porter: the Civil War years. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-5575-0353-4.

- —— (2006). Ellet's Brigade: The Strangest Outfit of All. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3186-2.

- Walke, Henry A. (2011). Holzer, Harold; McPherson, James M.; Robertson, James I. (eds.). Hearts Touched by Fire. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-6796-0430-3.

- Hoppin, James Mason (1874). Life of Andrew Hull Foote rear-admiral United States Navy. Harper & Brothers, New York.

- Johnson, Robert Underwood; Clough, Buel Clarence (1888). Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Vol III. New York: The Century Co.

- Joiner, Gary D. (2007). Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy: The Mississippi Squadron. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5098-8.

- —— (2007). Through the Howling Wilderness: The 1864 Red River Campaign and Union Failure in the West. Univ. of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9781572335448.

- Knight, James R. (2011). The Battle of Fort Donelson: No Terms but Unconditional Surrender. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-6142-3083-0.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1885). The Navy in the Civil War. New York, Charles Scribner's sons.

- —— (1883). The gulf and inland waters. New York, Scribner's Sons.

- —— (1905). Admiral Farragut. New York : The University Society. ( • Plain text format)

- McCaul, Edward B. (2014). To Retain Command of the Mississippi: The Civil War Naval Campaign for Memphis. Univ. of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-6219-0088-7.

- Patterson, Benton Rain (2010). The Mississippi River Campaign, 1861–1863: The Struggle for Control of the Western Waters. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5900-1.

- Phelps, Oliver Seymour; Servin, A. T. (1889). The Phelps family of America and their English ancestors, volume 2. Pittsfield, Mass., Eagle Pub. Co.

- Porter, David Dixon (1886). The Naval History of the Civil War. New York, Sherman Publishing Co.

- —— (1885). Incidents and anecdotes of the Civil War. New York, D. Appleton and Co.

- Pratt, Fletcher (1956). Civil War on Western Waters. Holt.

- Prushankin, Jeffery S. (2005). A Crisis in Confederate Command. ISBN 978-0-8071-4067-3.

- Scharf, John Thomas (1887). History of the Confederate States navy from its organization to the surrender of its last vessel. New York, Rogers & Sherwood.

- Sherman, William T. (1890). Personal memoirs of Gen. W.T. Sherman. 1. Charles L. Webster & Co.

- Slagle, Jay (1996). Ironclad Captain: Seth Ledyard Phelps & the U.S. Navy, 1841–1864. Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8733-8550-3.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- Soley, James Russell (1903). Admiral Porter. New York, D. Appleton & Company. ( • Plain text format)

- Stern, Philip Van Doren (1962). The Confederate Navy. Doubleday & Company.

- Williams, Paul Kelsey (November 2005). "Scenes from the Past…" (PDF). The InTowner. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-21. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- "Sources on U.S. Naval History homepage, Repository List for Missouri". Naval Historical Center, United States Navy. 2002-05-10. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- Gilder, R.W.; Lewis, W., eds. (1887). Battles and Leaders Of the Civil War. "Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers", Vol. 1; New York, The Century Company.

- "Oak Hill Cemetery, Georgetown, D.C. ; Lot 387 East" (PDF). Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- Further reading

- Brooksher, William R. (1996). War Along the Bayous: The 1864 Red River Campaign in Louisiana. Brassey. ISBN 9781574881394.

- Crandall, Warren Daniel; Newell, Isaac Denison (1907). History of the ram fleet and the Mississippi marine brigade in the war for the union on the Mississippi and its tributaries. The story of the Ellets and their men. St. Louis Press of Buschart Brothers. – Google eBook

- Konstan, Angus (20 December 2012). Union River Ironclad 1861–65. Bloomsbury Publishing Company. ISBN 9781782008392.

- Roberts, William H. (30 August 2007). Civil War Ironclads: The U.S. Navy and Industrial Mobilization. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8751-2.

- Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers (1908). The Union Army: The navy. Federal Publishing Company.

- Smith, Myron J., Jr. (2010). The USS Carondelet: A Civil War Ironclad on Western Waters. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-5609-3.

- —— (2011). The CSS Arkansas: A Confederate Ironclad on Western Waters. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-8485-0.

- —— (2012). Tinclads in the Civil War: Union Light-Draught Gunboat Operations on Western Waters, 1862–1865. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-5703-8.

- —— (2013). The Timberclads in the Civil War: The Lexington, Conestoga and Tyler on the Western Waters. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-7721-0.

- Tomblin, Barbara Brooks (2016). The Civil War on the Mississippi: Union Sailors, Gunboat Captains, and the Campaign to Control the River. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-6704-6.

- Constitution of the Mississippi Squadron Association

- External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Seth Ledyard Phelps. |

- DANFS : "Old Navy" Ship Photo Archive

- Seth Ledyard Phelps Letterbook Missouri History Museum Archives

- Seth Ledyard Phelps at Find a Grave

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Dennison |

President of the D.C. Board of Commissioners 1878–1879 |

Succeeded by Josiah Dent |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Stephen A. Hurlbut |

United States Minister to Peru April 24, 1884 – June 24, 1885 |

Succeeded by Charles W. Buck |