Tai peoples

Tai people refers to the population of descendants of speakers of a common Tai language, including sub-populations that no longer speak a Tai language. There is a total of about 93 million people of Tai ancestry worldwide, with the largest ethnic groups being Dai, Thais, Isan, Tai Yai, Lao, Ahom, and Northern Thai peoples.

Distribution of Tai people | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Southeast Asia Myanmar (Tai Yai) Laos Thailand Vietnam South Asia India (Tai Khamti, Tai Ahom, Tai Phake, Tai Aiton, Tai Khamyang and Tai Turung) East Asia China (Dai people, Zhuang people, Bouyei people) | |

| Languages | |

| Tai languages | |

| Religion | |

| Theravada Buddhism, Ahom religion , Tai folk religion, Hinduism, Islam, Animism, Shamanism |

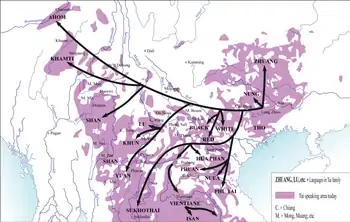

The Tai are scattered through much of South China and Mainland Southeast Asia, with some (e.g. Ahom, Khamti, Tai Phake) inhabiting parts of Northeast India. Tai peoples are both culturally and genetically very similar and therefore primarily identified through their language.

Names

Speakers of the many languages in the Tai branch of the Tai–Kadai language family are spread over many countries in Southern China, Indochina and Northeast India. Unsurprisingly, there are many terms used to describe the distinct Tai peoples of these regions.

According to Michel Ferlus, the ethnonyms Tai/Thai (or Tay/Thay) would have evolved from the etymon *k(ə)ri: 'human being' through the following chain: kəri: > kəli: > kədi:/kədaj (-l- > -d- shift in tense sesquisyllables and probable diphthongization of -i: > -aj).[1][2] This in turn changed to di:/daj (presyllabic truncation and probable diphthongization -i: > -aj). And then to *dajA (Proto-Southwestern Tai) > tʰajA2 (in Siamese and Lao) or > tajA2 (in the other Southwestern and Central Tai languages by Li Fangkuei). Michel Ferlus' work is based on some simple rules of phonetic change observable in the Sinosphere and studied for the most part by William H. Baxter (1992).[2]

The ethnonym and autonym of the Lao people (lǎo 獠) together with the ethnonym Gelao (Gēlǎo 仡佬), a Kra population scattered from Guìzhōu (China) to North Vietnam, and Sino-Vietnamese 'Jiao' as in Jiaozhi (jiāo zhǐ 交趾), the name of North Vietnam given by the ancient Chinese, would have emerged from the Austro-Asiatic *k(ə)ra:w 'human being'.[3][2]

The etymon *k(ə)ra:w would have also yielded the ethnonym Keo/ Kæw kɛːwA1, a name given to the Vietnamese by Tai speaking peoples, currently slightly derogatory.[4] In fact, Keo/ Kæw kɛːwA1 was an exonym used to refer to Tai speaking peoples, as in the epic poem of Thao Cheuang, and was only later applied to the Vietnamese.[5] In Pupeo (Kra branch), kew is used to name the Tay (Central Tai) of North Vietnam.[1]

The name "Lao" is used almost exclusively by the majority population of Laos, the Lao people, and two of the three other members of the Lao-Phutai subfamily of Southwestern Tai: Isan speakers (occasionally), the Nyaw or Yaw and the Phu Thai.

The Zhuang in China do not constitute an autonymic unity: in various areas in Guangxi they refer to themselves as powC2 ɕu:ŋB2, pʰoB2 tʰajA2, powC2 ma:nA2, powC2 ba:nC1, or powC2 lawA2, while those in Yunnan use the following autonyms: puC2 noŋA2, buB2 dajA2, or buC2 jajC1 (=Bouyei, bùyi 布依).[6] The Zhuang do not constitute a linguistic unity either, because Chinese authorities include within this group some distinct ethnic groups such as the Lachi speaking a Kra language.[6]

The Nung living on both sides of the Sino-Vietnamese border have their ethnonym derived from clan name Nong (儂 / 侬), whose bearers dominated what are now north Vietnam and Guangxi in the 11th century AD. In 1048, a Nong general, Nong Zhigao, revolted against Annamese rule, and then marched eastwards to besiege Guangzhou in 1052.

Another name that's shared between the Nung, the Tay, and the Zhuang living along the Sino-Vietnamese border is Tho, which literally means autochthonous. However, this term was also applied to the Tho people, who are a separate group of indigenous speakers of Vietic languages, who have come under the influence of Tai culture

History

The Tai peoples, from Guangxi began to move southwestward in the first millennium CE, eventually spreading across the whole of mainland Southeast Asia.[7] Based on layers of Chinese loanwords in proto-Southwestern Tai and other historical evidence, Pittayawat Pittayaporn (2014) proposes that the southwestward migration of Tai-speaking tribes from the modern Guangxi and northern Vietnam to the mainland of Southeast Asia must have taken place sometime between the 8th-10th centuries.[8] Tai speaking tribes migrated southwestward along the rivers and over the lower passes into Southeast Asia, perhaps prompted by the Chinese expansion and suppression. Chinese historical texts record that, in 722 AD, 400,000 'Lao'[lower-alpha 1] rose in revolt behind Mai Thúc Loan, who declared himself the king of Nanyue in Guangdong.[9][10] After the 722 revolt, some 60,000 were beheaded.[9] In 726, after the suppression of a rebellion by a 'Lao' leader in the present-day Guangxi, over 30,000 rebels were captured and beheaded.[10] In 756, another revolt attracted 200,000 followers and lasted four years.[11] In the 860s, many local people in what is now north Vietnam sided with attackers from Nanchao, and in the aftermath some 30,000 of them were beheaded.[11][12] In the 1040s, a powerful matriarch-shamaness by the name of A Nong, her chiefly husband, and their son, Nong Zhigao, raised a revolt, took Nanning, besieged Guangzhou for fifty seven days, and slew the commanders of five Chinese armies sent against them before they were defeated, and many of their leaders were killed.[11] As a result of these three bloody centuries, the Tai began to migrate southwestward.[11]

The Tai, form their new home in Southeast Asia, were influenced by the Khmer and the Mon and most importantly Buddhist India.

Languages

Tai languages spoken today use incredibly diverse scripts, from Chinese Characters to Abugida scripts. Theigh diversity of Kra–Dai languages in southern China possibly points to the origin of the Kra–Dai language family in southern China. The Tai branch moved south into Southeast Asia only around 1000 AD. Epigraphic materials from Chu texts show clear substrate influence predominantly from Tai-Kadai, and a few items of Austroasiatic and Hmong-Mien origin.[13][14]

External relationships

In a paper published in 2004, Linguist Laurent Sagart hypothesized that the proto-Tai–Kadai language originated as an Austronesian language that migrants carried from Taiwan to mainland China. Afterwards, the language was then heavily influenced by local languages from Sino-Tibetan, Hmong–Mien, or other families, borrowing much vocabulary and converging typologically.[15][16] Later, Sagart (2008) introduces a numeral-based model of Austronesian phylogeny, in which Tai-Kadai is considered as a later form of FATK,[lower-alpha 2] a branch of Austronesian belonging to subgroup Puluqic developed in Taiwan, whose speakers migrated back to the mainland, both to Guangnorthe Hainan and northern Vietnam around the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE.[17] Upon their arrival in this region, they underwent linguistic contact with an unknown population, resulting in a partial relexification of FATK vocabulary.[18] On the other hand, Weera Ostapirat supports a coordinate relationship between Tai-Kadai and Austronesian, based on a number of phonological correspondences.[19] The following are Tai-Kadai and Austronesian lexical items showing the genetic connection between these two language families:[20]

|

|

- PAN = proto-Austronesian, PMP = proto-Malayo-Polynesian, PTK = proto-Tai-Kadai

- M = Mak, Bd = Hlai of Baoding, G = Gelao, Tm = ?, By = Buyang, Lk = Lakkja, K = Kam, Ml = Mulam, Ts = Hlai of Tongshi

- Ostapirat (2013:3-8) did not provide full reconstructed forms for many of the proto-Tai-Kadai lexical items cited in the above tables

The connection between Austronesian and Tai-Kadai can also be found in some common cultural practices. Roger Blench (2008) demonstrates that dental evulsion, face-tattooing, teeth-blackening and snake cults are shared between the Taiwanese Austronesian and Tai-Kadai population in Southern China.[22][23]

Genetics

Tai people tend to have high frequencies of Y-DNA haplogroup O-M95 (including its O-M88 subclade, which also has been found with high frequency among Vietnamese and among Kuy people in Laos, where they are also known as Suy,[24] Soai, or Souei, and Cambodia[25]), moderate frequencies of Y-DNA haplogroup O-M122 (especially its O-M117 subclade, like speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages), and moderate to low frequencies of haplogroup O-M119. It is believed that the O-M119 Y-DNA haplogroup is associated with both the Austronesian people and the Tai. The prevalence of Y-DNA haplogroup O-M175 among Austronesian and Tai peoples suggests a common ancestry with speakers of the Austroasiatic, Sino-Tibetan, and Hmong–Mien languages some 30,000 years ago in China (Haplogroup O (Y-DNA)). Y-DNA haplogroup O-M95 is found at high frequency among most Tai peoples, which is a trait that they share with the neighboring ethnic Austroasiatic peoples as well as Austronesian peoples in Mainland Southeast Asia (e.g. Cham in Bình Thuận Province of Vietnam,[26] Jarai in Ratanakiri Province of Cambodia[25][27]), Malaysia, Singapore, and western Indonesia. Y-DNA haplogroups O-M95, O-M119, and O-M122 all are subclades of O-M175, a genetic mutation that has been estimated to have originated approximately 40,000 years ago, somewhere in China.[28]

A recent genetic and linguistic analysis in 2015 showed great genetic homogeneity between Kra-Dai speaking people, suggesting a common ancestry and a large replacement of former non-Kra-Dai groups in Southeast Asia. Kra-Dai populations are closest to southern Chinese and Taiwanese populations.[29]

Tai social organization

The Tai practice a type of feudal governance that is fundamentally different from that of the Han Chinese people, and is especially adapted to state formation in ethnically and linguistically diverse montane environments centered on valleys suitable for wet-rice cultivation.[30] The form of society is a highly stratified one.[30]

List of Southwestern Tai peoples

Northern branch

Chiang Saen branch

Southern group

Southwestern Tai groups and names in China

| Chinese | Pinyin | Tai Lü | Tai Nüa | Thai | Conventional | Area(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 傣仂 (西雙版納傣) | Dǎilè (Xīshuāngbǎnnà Dǎi) |

tai˥˩ lɯː˩ | ไทลื้อ | Tai Lü, Tai Lue | Xishuangbanna (China) | |

| 傣那 (德宏傣) | Dǎinà (Déhóng Dǎi) |

tai˥˩ nəː˥ | tai le6 | ไทเหนือ, ไทใต้คง | Tai Nüa, Northern Tai, Upper Tai, Chinese Shan | Dehong (China); Burma |

| 傣擔 | Dǎidān | tai˥˩ dam˥ | ไทดำ, ลาวโซ่ง, ผู้ไท | Tai Dam, Black Tai, Tai Lam, Lao Song Dam*, Tai Muan, Tai Tan, Black Do, Jinping Dai, Tai Den, Tai Do, Tai Noir, Thai Den | Jinping (China), Laos, Thailand | |

| 傣繃 | Dǎibēng | tai˥˩pɔːŋ˥ | ไทเมา | Tay Pong | Ruili, Gengma (China), along the Mekong | |

| 傣端 | Dǎiduān | tai˥˩doːn˥ | ไทขาว | White Tai, Tày Dón, Tai Khao, Tai Kao, Tai Don, Dai Kao, White Dai, Red Tai, Tai Blanc, Tai Kaw, Tày Lai, Thai Trang | Jinping (China) | |

| 傣雅 | Dǎiyǎ | tai˥˩jaː˧˥ | ไทหย่า | Tai Ya, Tai Cung, Cung, Ya | Xinping, Yuanjiang (China) | |

| 傣友 | Dǎiyǒu | tai˥˩jiu˩ | ไทแดง | Yuanyang (China), along the Red River | ||

| * lit. "Lao [wearing] black trousers" | ||||||

Other Tai peoples and languages

Listed below are lesser-known Tai peoples and languages.[31]

- Bajia 八甲 - 1,106 people in Mengkang Village 勐康村,[32] Meng'a Township 勐阿镇, Menghai County, Yunnan, who speak a language closely related to Tai Lü. They are classified by the Chinese government as ethnic Dai people. In Meng'a Town, they are in the village clusters of Mengkang 勐康[32] (in Shangnadong 上纳懂,[33] Xianadong 下纳懂,[34] and Mandao 曼倒[35]), Hejian 贺建[36] (in villages 6, 7, and 8), and Najing 纳京[37] (in villages 6,[38] 7,[39] and 8).[40][41] Zhang (2013) reports that there are 218 households and 816 people in 14 villages, and that the Bajia language is mutually intelligible with Tai. Another group of Bajia people in Manbi Village 曼必村,[42] Menghun Town 勐混镇, Menghai County, Yunnan (comprising 48 households and 217 persons) has recently been classified by the Chinese government as ethnic Bulang people.[40]

- Tai Beng 傣绷[43] - over 10,000 people in Yunnan Province, China. Also in Shan State, Myanmar. In China, they are in Meng'aba 勐阿坝, Mengma Town 勐马镇, Menglian County (in the three villages of Longhai 龙海,[44] Yangpai 养派, and Guangsan 广伞); Mangjiao Village 芒角村, Shangyun Township 上允乡, Lancang County (in the 2 villages of Mangjing 芒京[45] and Mangna 芒那[46]); Cangyuan County (in Mengjiao 勐角 and Mengdong 勐董 townships); Gengma County (in Mengding 勐定 and Mengsheng 勐省 townships); Ruili City (in small populations scattered along the border).

- Han Tai - 55,000 people in the Mengyuan County, Xishuangbanna Prefecture, Yunnan, China. Many Han Tai also speak Tai Lu (Shui Tai), the local lingua franca.

- Huayao Tai - 55,000 people (as of 1990) in Xinping and Mengyang Counties, Yunnan. It may be similar to Tai Lu.

- Lao Ga - 1,800 people mostly in Ban Tabluang, Ban Rai District, Uthai Thani Province, Thailand. Their language is reportedly similar to Lao Krang and Isan.

- Lao Krang - 50,000+ people in the provinces of Phichit, Suphan Buri, Uthai Thani, Chai Nat, Phitsanulok, Kamphaeng Phet, Nakhon Pathom and Nakhon Sawan, Thailand. Their language is similar to Isan and Lao. Tai Krang is not to be confused with Tai Khang, a Tai-speaking group of Laos numbering 5,000 people.

- Lao Lom - 25,000 people in Dan Sai District of Loei Province (locally known as the Lao Loei or Lao Lei), Lom Kao District of Phetchabun Province, and Tha Bo District of Nong Khai Province (locally known as the Tai Dan). The Lao Lom were first studied by Joachim Schliesinger in 2001. Unclassified Southwestern Tai language.

- Lao Ngaew - 20,000 to 30,000 people in Lop Buri Province (especially Ban Mi and Khok Samrong districts), the Tha Tako District of Nakhon Sawan Province and scattered parts of Singburi, Saraburi, Chaiyaphum, Phetchabun, Nong Khai and Loei provinces. Originally from eastern Xiengkhouang and western Huaphan provinces of Laos. Their language is similar to Isan.

- Lao Ti - 200 people in the 2 villages of Ban Goh and Nong Ban Gaim in Chom Bung District, Ratchaburi Province, Thailand. Originally from Vientiane in Laos. Their language is similar to Lao and Isan.

- Lao Wiang - 50,000+ people in Prachinburi, Udon Thani, Nakhon Sawan, Nakhon Pathom, Chai Nat, Lopburi, Saraburi, Phetchaburi and Roi Et. Originally from Wiang Chan (Vientiane) in Laos. Their language is similar to Lao.

- Paxi - 1,000+ people (as of 1990) in 2 villages 8 km from Menghai Town, at the foot of Jingwang Mountain in Xishuangbanna.

- Tai Bueng - 5,700 people in 2 villages of Phatthana Nikhom District, Lopburi Province, Thailand. The Tai Bueng live in the villages of Ban Klok Salung (pop. 5,000) and Ban Manao Hwan (pop. 600). Unclassified Tai language.

- Tai Doi ('mountain people') - 230 people (54 families) as of 1995 in Long District of Luang Namtha, Laos. Their language is likely Palaungic.

- Tai Gapong ('brainy Tai') - 3,200+ people; at least 2,000 people (500+ households) in Ban Varit, Waritchapum District, Sakhon Nakhon Province; also live with the Phutai and Yoy. The Tai Gapong claim to have originated in Borikhamxai Province, Laos.

- Tai He - 10,000 people in Borikhamxai Province, Laos: in Viangthong and Khamkeut Districts; also in Pakkading and Pakxan Districts. Unclassified Tai language.

- Tai Kaleun - 7,000 people mostly in Khamkeut District, Borikhamxai Province, Laos; also in Nakai District. 8,500 people in Thailand: the provinces of Mukdahan (Don Tan and Chanuman districts), Nakhon Phanom (Muang District) and parts of Sakhon Nakhon Province. The Tai Kaleung speak a Lao dialect.

- Tai Khang - 5,600+ people in Xam-Tai District, Houaphan Province, Laos; also in Nongkhet District of Xiangkhoang Province, and Viangthong District of Borikhamxai Province. Unclassified Tai language.

- Tai Kuan (Khouane) - 2,500 people in Viengthong District, Borikhamxai Province, Laos: near the banks of the Mouan River.

- Tai Laan - 450 people in a few villages of Kham District, Xiangkhoang Province, Laos. Unclassified Tai language.

- Tai Loi - 1,400 people in Namkham, Shan State, Burma; 500 people in Long District, Luang Namtha Province, Laos; possibly also in Xishuangbanna Prefecture, China, since some Tai Loi in Burma say they have relatives in China. Their language may be related to and probably also closely related to Palaung Pale.

- Tai Men - 8,000 people in Borikhamxai Province, Laos: mostly in Khamkeut District, but also in Vienthong, Pakkading, and Pakxan Districts. They speak a Northern Tai language.

- Tai Meuiy - 40,000+ people in Borikhamxai, Khammouan, Xiengkhouang, and Houaphan (just outside the town of Xam Neua) provinces of Laos. Their language is reportedly similar to Tai Dam and Tai Men.

- Tai Nyo - 13,000 people in Pakkading District, Borikhamxai Province, Laos; 50,000 people in northeastern Thailand, where they are better known as Nyaw. Similar to Lao of Luang Prabang.

- Tai Pao - 4,000 people in Viangthong, Khamkeut and Pakkading districts of Borikhamxai Province, Laos. They live near the Tai He and may be related to them. Unclassified Tai language.

- Tai Peung - 1,000 people in Kham District, Xiengkhouang Province, Laos. They live near the Tai Laan and Tai Sam. Unclassified Tai language.

- Tai Pong 傣棚 - perhaps as many as 100,000 people in along the Honghe River of southeastern, Yunnan, China, and possibly also in northern Vietnam. Subgroups include the Tai La, Tai You, and probably also Tai Ya (which includes Tai Ka and Tai Sai). Unclassified Tai language.

- Tai Sam - 700 people in Kham District, Xiengkhuoang Province, Laos. Neighboring peoples include the Tai Peung and Tai Laan. Unclassified Tai language.

- Tai Song - 45,000+ people in Phetchabun, Phitsanulok, Nakhon Sawan (Tha Tako District), Ratchaburi (Chom Bung District), Suphan Buri (Song Phinong District), Kanchanaburi, Chumphon and Nakhon, and Pathom (Muang District). Also called Lao Song. They are a subgroup of the Tai Dam.

- Tai Wang - 10,000 people in several villages in Viraburi District, Savannakhet Province, Laos; 8,000 in and around the city of Phanna Nikhom, Sakhon Nakhon Province, Thailand. Their language is related to but distinct from Phutai.

- Tai Yuan ('Northern Thai') - 6,000,000 people in Northern Thailand and possibly 10,000 people in Houayxay and Pha-Oudom districts of Bokeo Province, Luang Namtha District of Luang Namhta Province, Xai District of Oudomxai Province, and Xaignabouri District of Xaignabouri Province. They speak a Southwestern Tai language.

- Tak Bai Thai - 24,000 people in southern Thailand (in Narathiwat, Pattani, and Yala provinces) and northern Malaysia. Their name comes from the town of Tak Bai in Narathiwat Province. Their language is highly different from nearby Southern Thai dialects, and may be related to the Sukkothai dialect further up north.

- Yang - 5,000 people in Phongsaly, Luang Namtha, and Oudomxay provinces, Laos (Chazee 1998).[47]

- Kap Kè (‘gekko’ people) now refer to themselves as Nyo. The Nyo proper reside mostly along the Mekong between Hinboun and Pakxanh and also in Thailand. The Kap Kè claim they are the same as the Nyo of Ban Khammouane in Khamkeut District, Bolikhamsai province, Laos. Another Kap Kè group of about 40 households originally from Sop Khom has now resettled in Sop Phouan. This group claims to be from Ban Faan, about 1 kilometer from Sop Khom.[48]

- Phuk (sometimes pronounced without the final –k as Phu’) - According to themselves as well as other ethnic groups, the Phuk closely resemble the Kap Kè and originally came from nearby locations, referred to as phiang phuk and phiang Kap Kè. They were originally from the villages of Fane, Ka’an and Vong Khong.[48]

- Thay Bo - located on the Nakai plateau in central Laos, along the middle Hinboun River, east of the Kong Lo cave and the Phon Tiou tin mine, and in Ban Na Hat and near Na Pè, close to the Vietnamese border. Bo means ‘a mine,’ referring people who worked either in the salt mines on the Nakai Plateau, or at the tin mine. Many older generation people speak a Vietic language as well, apparently Maleng, as spoken in the village of Song Khone on the Nam Sot River, a main tributary of the Nam Theun, although this has not been verified.[48]

- Kha Bo - In 1996, the Bo of Sop Ma village reported that they were "born from the Kha," a reference to their Vietic origins, and in that village there was intermarriage with the Maleng of Song Khone. They are distinct from the Thay Bo of Hinboun. The Kha Bo on the Nakai plateau speak Nyo, whereas nowadays the Thay Bo of Hinboun speak Lao or Kaleung. The Ahoe, original inhabitants of the northwestern part of the Nakai Plateau, had also been relocated to Hinboun during the Second War of Indochina, and returned to their homeland speaking Hinboun Nyo as a second language.[48]

In Burma, there are also various Tai peoples that are often categorized as part of a larger Shan ethnicity (see Shan people#Tai groups).

Diaspora

Throughout Asia

In other parts of Asia, substantial Thai communities can be found in Japan, Taiwan and the United Arab Emirates.

Tai of North America

The United States is home to a significant population of Thai, Lao, Tai Kao, Isan, Lu, Phutai, Tai Dam, Tay and Shan people. There are a significant number of Thai and Lao people living in Canada as well.

Tai of Europe

The most significant communities of Tai peoples in Europe are in the Lao communities of the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Switzerland, the Isan communities of the United Kingdom and Iceland, the Thai communities of Finland, Iceland and Norway, the Tai Dam and Tay communities of France, and the Southern Thai community of the United Kingdom.

Thai of Oceania

There is a sizable Thai community in Australia, as well as a Northeastern Thai community in New Zealand.

Notes

- The term "Lao" used in this context refers to Tai-Kadai speaking peoples resided in what are now Guangdong, Guangxi, and northern Vietnam in general. It is unnecessarily applied solely to the ancestor of the Lao.

- Formosan ancestor of Tai-Kadai.

- According to Ostapirat (2005:119), glosses are given according to Tai-Kadai. The typical meaning of this word in Austronesian is *paqiC "bitter".

- The typical PAN root for "bird" is *qayam. The cited form *manuk is reconstructed for PMP, with semantic shift from "chicken" to "bird".

- According to Ostapirat (2005:119), glosses are given according to Tai-Kadai. The typical meaning of this word in Austronesian is *qalejaw "sun".

- According to Ostapirat (2005:119), glosses are given according to Tai-Kadai. The typical meaning of this word in Austronesian is *pudeR "kidney".

References

- Ferlus 2009, p. 3.

- Pain 2008, p. 646.

- Ferlus 2009, pp. 3-4.

- Ferlus 2009, p. 4.

- Chamberlain 2016, pp. 69-70.

- Pain 2008, p. 642.

- Evans 2002, p. 2.

- Pittayaporn 2014, pp. 47–64.

- Baker 2002, p. 5.

- Taylor 1991, p. 193.

- Baker & Phongpaichit 2017, p. 26.

- Taylor 1991, pp. 239-249.

- Behr 2006, pp. 1-21.

- Behr 2009, pp. 1-48.

- Sagart 2004, pp. 411-440.

- Blench 2004, p. 12.

- Sagart 2008, pp. 146-152.

- Sagart 2008, p. 151.

- Ostapirat 2013, pp. 1-10.

- Ostapirat 2005, pp. 110-122.

- Ostapirat 2013, pp. 3-8.

- Blench 2009, pp. 4-7.

- Blench 2008, pp. 17-32.

- Cai, X; Qin, Z; Wen, B; Xu, S; Wang, Y; et al. (2011). "Human Migration through Bottlenecks from Southeast Asia into East Asia during Last Glacial Maximum Revealed by Y Chromosomes". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e24282. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024282. PMC 3164178. PMID 21904623.

- Zhang, X; Kampuansai, J; Qi, X; Yan, S; Yang, Z; et al. (2014). "An Updated Phylogeny of the Human Y-Chromosome Lineage O2a-M95 with Novel SNPs". PLOS ONE. 9 (6): e101020. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101020. PMID 24972021.

- He, J-D; Peng, M-S; Quang, HH; Dang, KP; Trieu, AV; et al. (2012). "Patrilineal Perspective on the Austronesian Diffusion in Mainland Southeast Asia". PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e36437. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036437. PMID 22586471.

- Zhang, Xiaoming; Liao, Shiyu; Qi, Xuebin; et al. (2015). "Y-chromosome diversity suggests southern origin and Paleolithic backwave migration of Austro-Asiatic speakers from eastern Asia to the Indian subcontinent". Scientific Reports. 5: 15486. doi:10.1038/srep15486. PMC 4611482. PMID 26482917.

- Poznik, G David; Xue, Yali; Mendez, Fernando L; Willems, Thomas F; Massaia, Andrea; Wilson Sayres, Melissa A; Ayub, Qasim; McCarthy, Shane A; Narechania, Apurva (25 April 2016). "Punctuated bursts in human male demography inferred from 1,244 worldwide Y-chromosome sequences". Nature Genetics. 48 (6): 593–599. doi:10.1038/ng.3559. ISSN 1061-4036. PMC 4884158. PMID 27111036.

- Srithawong, Suparat; Srikummool, Metawee; Pittayaporn, Pittayawat; Ghirotto, Silvia; Chantawannakul, Panuwan; Sun, Jie; Eisenberg, Arthur; Chakraborty, Ranajit; Kutanan, Wibhu (2015). "Genetic and linguistic correlation of the Kra-Dai-speaking groups in Thailand". Journal of Human Genetics. 60 (7): 371–380. doi:10.1038/jhg.2015.32. ISSN 1435-232X. PMID 25833471. S2CID 21509343.

- Holm 2014, p. 33.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vdefault.aspx?departmentid=105122

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vIndex.aspx?departmentid=105132

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vIndex.aspx?departmentid=105131

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vIndex.aspx?departmentid=105126

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vdefault.aspx?departmentid=105157

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vdefault.aspx?departmentid=105139

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vIndex.aspx?departmentid=105145

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vIndex.aspx?departmentid=105146

- http://www.12bn.net/article/article_3982.html

- Zhang Yanju 张艳菊. 2013. 试论民族识别与归属中的认同问题-以云南克木人、莽人、老品人、八甲人民族归属工作为例. 广西民族研究2013年第4期 (总第114期).

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vIndex.aspx?departmentid=157200

- Gao Lishi 高立士. 1999. 傣族支系探微. 中南民族学院学报 (哲学社会科学版). 1999 年第1 期 (总第96 期).

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vIndex.aspx?departmentid=116917

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vIndex.aspx?departmentid=143591

- http://www.ynszxc.gov.cn/villagePage/vIndex.aspx?departmentid=143592

- Chazee, Laurent. 1998. Rural and ethnic diversities in Laos with special focus on the northern provinces. Presented for the Workshop on "Rural and Ethnic diversities in Laos with special focus on Oudomxay and Sayabury development realities", in Oudomxay province, 4–5 June 1998. SESMAC projects Lao/97/002 & Lao/97/003: Strengthening Economic and Social Management Capacity, Sayabury and Oudomxay provinces.

- Chamberlain, James. 2016. Vietic Speakers and their Remnants in Khamkeut District (Old Khammouane).

Works cited

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017), A History of Ayutthaya, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4.

- Baker, Chris (2002), "From Yue To Tai" (PDF), Journal of the Siam Society, 90 (1–2): 1–26.

- Behr, Wolfgang (2017). "The language of the bronze inscriptions". In Shaughnessy, Edward L. (ed.). Kinship: Studies of Recently Discovered Bronze Inscritpions from Ancient China. The Chinese University Press of Hong Kong. pp. 9–32. ISBN 978-9-629-96639-3.

- ——— (2009). "Dialects, diachrony, diglossia or all three? Tomb text glimpses into the language(s) of Chǔ". TTW-3, Zürich, 26.-29.VI.2009, "Genius Loci": 1–48.

- ——— (2006). "Some Chŭ 楚 words in early Chinese literature". EACL-4, Budapest: 1–21.

- Blench, Roger (2014), Suppose we are wrong about the Austronesian settlement of Taiwan? (PDF).

- ——— (2009) [2008], "THE PREHISTORY OF THE DAIC (TAIKADAI) SPEAKING PEOPLES AND THE HYPOTHESIS OF AN AUSTRONESIAN CONNECTION" (PDF), The 12th EURASEAA Meeting, Leiden, 1-5th September.CS1 maint: location (link)

- ——— (2008), "THE PREHISTORY OF THE DAIC (TAIKADAI) SPEAKING PEOPLES AND THE HYPOTHESIS OF AN AUSTRONESIAN CONNECTION" (PDF), Euraseaa, Leiden, 1-5th September.CS1 maint: location (link)

- ——— (2004), "Stratification in the peopling of China: how far does the linguistic evidence match genetics and archaeology?" (PDF), Human Migrations in Continental East Asia and Taiwan: Genetic, Linguistic and Archaeological Evidence in Geneva, Cambridge: 1–25.

- Chamberlain, James R. (2016), "Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam", Journal of the Siam Society, 104: 27–77.

- Ferlus, Michel (2009), "Formation of Ethnonyms in Southeast Asia", 42nd International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, Chiang Mai: 1–6.

- Holm, David (2014), "A Layer of Old Chinese Readings in the Traditional Zhuang Script", Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities: 1–45.

- Evans, Grant (2002), A short history of Laos : the land in between (PDF), Allen & Unwin, ISBN 978-1-86448-997-2.

- Ko, Albert Min-Shan; et al. (2014). "Early Austronesians: Into and Out Of Taiwan" (PDF). The American Journal of Human Genetics. 94 (3): 426–36. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.02.003. PMC 3951936. PMID 24607387.

- Ostapirat, Weera (2013). "Austro-Tai revisited" (PDF). Plenary Session 2: Going Beyond History: Reassessing Genetic Grouping in SEA the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, May 29–31, 2013, Chulalongkorn University: 1–10.

- ——— (2005), "Kra-dai and Austronesian: notes on phonological correspondences and vocabulary distribution" (PDF), in Sagart, Laurent; Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia; Blench, Roger (eds.), The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics, RoutledgeCurzon, pp. 107–131, ISBN 978-0-415-32242-3.

- Pain, Frédéric (2008), "An Introduction to Thai Ethnonymy: Examples from Shan and Northern Thai", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 128 (4): 641–662, JSTOR 25608449.

- Pittayaporn, Pittayawat (2014), "Layers of Chinese Loanwords in Proto-Southwestern Tai as Evidence for the Dating of the Spread of Southwestern Tai" (PDF), MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities, 17 (Special No. 20): 47–64, doi:10.1163/26659077-01703004.

- Sagart, Laurent; Hsu, Tze-Fu; Tsai, Yuan-Ching; Hsing, Yue-Ie C. (2017). "Austronesian and Chinese words for the millets". Language Dynamics and Change. 7 (2): 187–209. doi:10.1163/22105832-00702002.

- Sagart, Laurent (2008). "The expansion of Setaria farmers in East Asia". In Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia; Blench, Roger; Ross, Malcolm D.; Peiros, Ilia; Lin, Marie (eds.). Past Human Migrations in East Asia: Matching Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics (Routledge Studies in the Early History of Asia) 1st Edition. Routledge. pp. 133–157. ISBN 978-0-415-39923-4.

- ——— (2004), "The higher phylogeny of Austronesian and the position of Tai–Kadai" (PDF), Oceanic Linguistics, 43 (2): 411–444, doi:10.1353/ol.2005.0012, S2CID 49547647.

- Taylor, Keith W. (1991), The Birth of Vietnam, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0.

- Wei, Lan-Hai; Yan, Shi; Teo, Yik-Ying; Huang, Yun-Zhi; et al. (2017). "Phylogeography of Y-chromosome haplogroup O3a2b2-N6 reveals patrilineal traces of Austronesian populations on the eastern coastal regions of Asia". PLOS ONE. 12 (4): 1–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0175080. PMC 5381892. PMID 28380021.

External links

![]() Media related to Tai peoples at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tai peoples at Wikimedia Commons