Tegetthoff-class battleship

The Tegetthoff class (also called the Viribus Unitis class[4][5][6]) was a class of four dreadnought battleships built for the Austro-Hungarian Navy. Named for Austrian Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, the class was composed of SMS Viribus Unitis, SMS Tegetthoff, SMS Prinz Eugen, and SMS Szent István. Construction started on the ships shortly before World War I; Viribus Unitis and Tegetthoff were both laid down in 1910, Prinz Eugen and Szent István followed in 1912.[7] Three of the four warships were built in the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino shipyard in Trieste; Szent István was built in the Ganz-Danubius shipyard in Fiume, so that both parts of the Dual Monarchy would participate in the construction of the ships.[8][2] The Tegetthoff-class ships hold the distinction for being the first and only dreadnought battleships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy.[9]

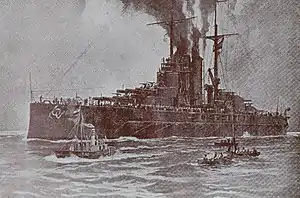

Viribus Unitis, the lead ship of the Tegetthoff-class battleships, in 1912 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Tegetthoff-class battleship |

| Builders: | |

| Operators: | |

| Preceded by: | Radetzky class |

| Succeeded by: | Ersatz Monarch class |

| Cost: | 60,600,000 Krone per ship[2] |

| Built: | 1910–1914 |

| In commission: | 1912–1918 |

| Completed: | 4 |

| Lost: | 2 |

| Scrapped: | 2 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 152 m (498 ft 8 in) |

| Beam: | 27.90 m (91 ft 6 in) |

| Draft: | 8.70 m (28 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power: | |

| Propulsion: | 4 shafts; 4 steam turbine sets[lower-alpha 3] |

| Speed: | 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph)[lower-alpha 4] |

| Range: | 4,200 nmi (7,800 km; 4,800 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 1,087[3] |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

Viribus Unitis and Tegetthoff were commissioned into the fleet in December 1912 and July 1913, respectively. Prinz Eugen followed in July 1914.[8] The smaller shipyards in Fiume resulted in a slower construction which was further delayed by the outbreak of the war, with Szent István commissioned into the fleet in December 1915.[3] This was too late for her to take part in the Bombardment of Ancona in which the remaining ships in the class saw action immediately following Italy's declaration of war on Austria-Hungary in May 1915.[10][11]

All of the Tegetthoffs were members of the 1st Battleship Division at the beginning of the war and were stationed out of the naval base at Pola.[12] Following the Bombardment of Ancona and the commissioning of Szent István, the four ships saw little combat due to the Otranto Barrage which prohibited the Austro-Hungarian Navy from leaving the Adriatic Sea.[11] In June 1918, in an attempt to earn safer passage for German and Austro-Hungarian U-boats through the Strait of Otranto, the Austro-Hungarian Navy attempted to break the Barrage with a major attack on the strait, but it was abandoned after Szent István was sunk by the Italian motor torpedo boat MAS-15 on the morning of 10 June.[13]

After the sinking of Szent István, the remaining three ships of the class returned to port in Pola where they remained for the rest of the war. When Austria-Hungary was facing defeat in the war in October 1918, the Austrian government decided to transfer Viribus Unitis to the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs in order to avoid having to hand the ship over to the Allied Powers. Renamed Jugoslavija, the ship was destroyed by an Italian mine in the Raid on Pola a day later.[1] Following the Armistice of Villa Giusti in November 1918, Prinz Eugen was ceded to France where she was sunk as a target ship in 1922, while Tegetthoff was handed over to Italy and scrapped between 1924 and 1925.[8] The wreck of Viribus Unitis was salvaged from Pola harbor and broken up between 1920 and 1930.[14]

Background

With the establishment of the Austrian Naval League in September 1904 and the October appointment of Vice-Admiral Rudolf Montecuccoli to the posts of Commander-in-Chief of the Navy (German: Marinekommandant) and Chief of the Naval Section of the War Ministry (German: Chef der Marinesektion),[15][16] the Austro-Hungarian Navy began an expansion program befitting a Great Power. Montecuccoli immediately pursued the efforts championed by his predecessor, Admiral Hermann von Spaun, and pushed for a greatly expanded and modernized navy.[17]

Additional motivations existed which led to the development of the Tegetthoff class beyond Montecuccoli's own plans for the navy. New railroads had been constructed through Austria's Alpine passes between 1906 and 1908, linking Trieste and the Dalmatian coastline to the rest of the Empire. Lower tariffs on the port of Trieste aided the expansion of the city and similar growth in Austria-Hungary's merchant marine. These changes necessitated the development of a new line of battleships capable of more than the defense of Austria-Hungary's coastline.[18]

Prior to the turn of the century, sea power had not been a priority in Austrian foreign policy and the navy had little public interest or support. However, the appointment of Archduke Franz Ferdinand – heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne and a prominent and influential supporter of naval expansion – to the position of admiral in September 1902 greatly increased the importance of the navy in the eyes of both the general public and the Austrian and Hungarian Parliaments.[19][20] Franz Ferdinand's interest in naval affairs stemmed primarily from his belief that a strong navy would be necessary to compete with Italy, which he viewed as Austria-Hungary's greatest regional threat.[21]

The Tegetthoff-class battleships were authorized when Austria-Hungary was engaged in a naval arms race with its nominal ally, Italy.[22][23] Italy's Regia Marina was considered the most important naval power in the region, which Austria-Hungary measured itself against, often unfavorably. The disparity between the Austro-Hungarian and Italian navies had existed for decades; in the late 1880s Italy boasted the third-largest fleet in the world, behind the French Navy and the British Royal Navy.[24][25] While that disparity had been somewhat equalized with the Imperial Russian Navy and German Imperial Navy surpassing the Italian Navy in 1893 and 1894 respectively,[24] by 1903 the balance began to shift towards Italy's favor with the Italians claiming 18 pre-dreadnoughts in commission or under construction compared to 6 Austro-Hungarian battleships.[25]

Following the construction of the final two Regina Elena-class battleships in 1903, the Italian Navy elected to construct a series of large cruisers rather than additional battleships. Furthermore, a major scandal involving the Terni steelworks' armor contracts led to a government investigation that postponed several naval construction programs for three years. These delays meant that the Italian Navy would not initiate construction on another battleship until 1909, and provided the Austro-Hungarian Navy with an opportunity to address the disparity between the two fleets.[20]

Austro-Italian naval arms race

As late as 1903 the Italian advantage in naval arms appeared so large that the difficulty of Austria-Hungary catching up to the Italian Navy, much less surpassing it, appeared insurmountable. Events changed, however, with the revolution in naval technology created by the launch of the British HMS Dreadnought in 1906 and the Anglo-German naval arms race that followed. The value of pre-dreadnought battleships declined rapidly and numerous ships in European navies were rendered obsolete, giving Austria-Hungary an opportunity to make up for past neglect in naval affairs. With an improved financial situation and budget from the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, and with Archduke Ferdinand and Admiral Montecuccoli both supportive of constructing a new class of modern battleships, the stage was set for the development of Austria-Hungary's first and only class of dreadnought battleships.[26][19]

Shortly after assuming command as Chief of the Navy, Montecuccoli drafted his first proposal for a modern Austrian fleet in the spring of 1905. It was to consist of 12 battleships, 4 armored cruisers, 8 scout cruisers, 18 destroyers, 36 high seas torpedo craft, and 6 submarines. While these plans were ambitious, they lacked any ships the size of the Tegetthoff class.[26] Additional proposals came from outside the Naval Section of the War Ministry. The Slovenian politician and prominent Trialist Ivan Šusteršič presented a proposal to the Reichsrat in 1905 calling for the construction of nine additional battleships.[27] The Austrian Naval League also presented its proposals for the construction of a series of dreadnoughts. Petitioning the Naval Section of the War Ministry in March 1909 to construct three dreadnoughts of 19,000 metric tons (18,700 long tons), the League justified its proposal by arguing that a strong navy would be necessary to protect Austria-Hungary's growing merchant marine, and that Italian naval spending was twice Austria-Hungary's.[28]

Following the construction of Austria-Hungary's last class of pre-dreadnought battleships, the Radetzky class,[7] Montecuccoli submitted his first proposal for true dreadnought battleships for the Austro-Hungarian Navy.[29] Taking advantage of political support for naval expansion he had obtained in both Austria and Hungary over the course of several years, and Austrian fears of a war with Italy over the Bosnian Crisis during the previous year, Montecuccoli drafted a new memorandum to Emperor Franz Joseph I in January 1909 proposing an enlarged Austro-Hungarian Navy consisting of 16 battleships, 12 cruisers, 24 destroyers, 72 seagoing torpedo boats, and 12 submarines. While this was a modified version of his 1905 plan, one notable change was the inclusion of four additional dreadnought battleships with a displacement of 20,000 metric tons (19,684 long tons) at load. These ships would become the Tegetthoff class.[30][31]

| Naval strength of Italy and Austria-Hungary in May 1909[32] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Italy | Austria-Hungary | Italian/Austro-Hungarian

tonnage ratio | ||

| Number | Tonnage | Number | Tonnage | ||

| Battleships | 10 (2 under construction) | 124,112 metric tons (122,152 long tons) | 9 (3 under construction) | 73,836 metric tons (72,670 long tons) | 1.7:1 |

| Armored cruisers | 8 (2 under construction) | 59,869 metric tons (58,923 long tons) | 3 | 18,992 metric tons (18,692 long tons) | 3.1:1 |

| Protected cruisers | 6 (1 under construction) | 14,605 metric tons (14,374 long tons) | 6 | 16,727 tonnes (16,463 long tons) | 0.9:1 |

| Torpedo vessels | 6 | 3,110 metric tons (3,061 long tons) | 6 | 2,730 metric tons (2,687 long tons) | 1.1:1 |

| Destroyers | 17 (2 under construction) | 5,698 metric tons (5,608 long tons) | 8 (4 under construction) | 3,200 metric tons (3,149 long tons) | 1.8:1 |

| High seas torpedo boats | 8 (8 under construction) | 5,936 metric tons (5,842 long tons) | 17 (7 under construction) | 3,400 metric tons (3,346 long tons) | 1.7:1 |

| Coastal torpedo boats | 59 | 5,254 metric tons (5,171 long tons) | 28 (14 under construction) | 2,410 metric tons (2,372 long tons) | 2.1:1 |

| Submarines | 7 (5 under construction) | 1,155 metric tons (1,137 long tons) | 2 (6 under construction) | 474 metric tons (467 long tons) | 2.4:1 |

| Total | 121 (20 under construction) | 219,759 metric tons (216,288 long tons) | 79 (34 under construction) | 121,769 metric tons (119,846 long tons) | 1.8:1 |

Proposals

Following up on Montecuccoli's memorandum, the Naval Section of the War Ministry submitted its specifications for the Tegetthoff-class battleships to Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino in October 1908, who in turn hired naval architect Siegfried Popper to produce a design. In December 1908, the Naval Section of the War Ministry also began a competition for the design of the Tegetthoff class, with the aim of producing alternate designs aside from those Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino would present.[33]

Emperor Franz Joseph I approved Montecuccoli's plan in January 1909, who subsequently circulated it among the governments in Vienna and Budapest.[30] In March, Popper presented five pre-project designs for the Tegetthoff class. These initial designs were effectively enlarged versions of the Radetzky class and lacked the triple turrets which would later be found on the Tegetthoffs.[34] In April 1909, Popper returned with a new set of proposals, named "Variant VIII" which included triple turrets.[35] That same month, Montecuccoli's memorandum found its way into Italian newspapers, sparking hysteria among the Italian people and politicians. The Italian Navy used the report as justification for initiating a new dreadnought program. In June 1909 Dante Alighieri was laid down at the naval shipyard in Castellammare di Stabia.[30]

Funding

Budget crisis

The development of Dante Alighieri left the Austro-Hungarian Navy in a precarious position. The Italian battleship was laid down largely due to the leaking of Montecuccoli's memorandum, while the proposal for constructing four new battleships still remained in the planning stages. Complicating the matter further was the collapse of Sándor Wekerle's government in Budapest, which left the Hungarian Diet without a prime minister for nearly a year. With no government in Budapest to pass a budget, efforts to secure funding and begin construction had stalled.[36]

The budget crisis likewise affected industries with close ties to the navy, particularly the Witkowitz Ironworks and the Škoda Works. With Radetzky nearing completion and Zrínyi the only remaining Austro-Hungarian battleship still under construction in the shipyards of Trieste, the major shipbuilding enterprises in Austria offered to begin construction on three dreadnoughts at their own financial risk, in exchange for promises from the Austro-Hungarian government that the battleships would be purchased as soon as the budget impasse had been resolved. After negotiations involving the ministries of foreign affairs, war and finance, the navy agreed to the offer but lowered the number of dreadnoughts that would be constructed before a budget was passed from three to two.[37] In his memoirs, former Austrian Field Marshal and Chief of the General Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf wrote that due to his belief in a future war with Italy, construction on the battleships should begin as soon as possible. He also worked to secure agreements to sell the dreadnoughts to, in his words, a "reliable ally" (which only Germany could claim to be) should the budget crisis fail to be resolved in short order.[38]

Facing potential backlash over constitutional concerns that the construction of the first two battleships committed Austria-Hungary to spend roughly 120 million Kronen without prior approval by either the Austrian Reichsrat or the Diet of Hungary, the deal remained secret.[39] In the event of the agreement being leaked to the press prior to the passage of a new naval budget, Montecuccoli drafted several explanations to justify the battleships' construction and the necessity to keep their existence a secret. These included the navy's urgent need to counter Italy's naval build up and desire to negotiate a lower price with their builders.[40] By the time the agreement was leaked to the public in April 1910 by the Arbeiter-Zeitung, the newspaper of Austria's Social Democratic Party, the plans had already been finalized and construction on the first two battleships, Viribus Unitis and Tegetthoff, was about to begin.[22]

Costs

The costs to construct the Tegetthoff-class battleships were enormous by the standards of the Austro-Hungarian Navy. While the Habsburg-class, Erzherzog Karl-class, and the Radetzky-class battleships cost the navy roughly 18, 26, and 40 million Kronen per ship,[40] each ship of the Tegetthoff class was projected to cost over 60 million Kronen.[2] Under the previous budgets for 1907 and 1908, the navy had been allocated some 63.4 and 73.4 million Kronen, which at the time was considered an inflated budget due to the construction of two Radetzkys. Montecuccoli worried that the general public and the legislatures in Vienna and Budapest would reject the need for the expensive ships, especially so soon after the political crisis in Budapest. The dramatic increase in spending meant that in 1909 the navy spent some 100.4 million Kronen, a huge sum at the time. This was done in order to rush the completion of the Radetzky-class battleships, though the looming construction of four dreadnoughts meant the Austro-Hungarian Navy would likely have to ask the government for a yearly budget much higher than 100 million Kronen.[40]

In order to guarantee funding for the ships from the Rothschild family in Austria, who owned the Witkowitz Ironworks, the Creditanstalt Bank, and had significant assets in both the Škoda Works and the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Archduke Franz Ferdinand personally courted Albert Salomon Anselm von Rothschild in order to obtain his family's monetary support until the government could buy the ships.[41][42]

Budget negotiations and passage

The budgets providing funding for the Tegetthoff class were finally approved after two meetings of the Austrian Reichsrat and the Diet of Hungary in October and November 1910, with opposition being rejected as the Italian Navy had laid down another three battleships during the summer.[43][22] The retroactive passage of the 1910 budget and the passage of the 1911 budget was secured between December and March with little opposition. István Tisza, who had won Hungary's 1910 Parliamentary election but instead chose to allow a government to form under Károly Khuen-Héderváry, secured passage of the budgets with his large parliamentary majority. This was done after it was agreed the contract for the battleship which would eventually become Szent István was to be awarded to the Ganz-Danubius shipyard in Fiume.[44] Tisza's political allies were likewise won over with bribes such as being appointed to the board of directors of the Adria Line.[45] Securing passage of the budgets in the Austrian Reichsrat had been comparatively easy. Karel Kramář, leader of the Young Czech Party, supported the budgets with the justification that he had "a certain weakness for the navy."[44] Šusteršič, leader of the Slovene bloc, rallied support by arguing that the battleships were in the best interests of the navy and the Slovenian people. German politicians supported the battleships' construction on the grounds that their existence made Austria-Hungary a more powerful ally for Germany. The final package included provisions which ensured that while the armor and guns of the Tegetthoff class were to be constructed within Austria, the electrical wiring and equipment aboard each ship was to be assembled in Hungary. Additionally, half of all ammunition for the battleships' guns would be purchased in Austria and half was to be bought in Hungary.[46] Only the Social Democrats opposed the budgets. Their leader, Karl Seitz, decried the worsening relations with Italy and called for negotiations with Rome to end the Austro-Italian naval arms race. In a sign of Austria-Hungary's strained relationship with her nominal ally Italy, the proposal failed with little support outside of Seitz' party. The budgets passed both parliaments with large majorities, ensuring that the financial questions regarding the construction of the ships were resolved.[44]

Design

General characteristics

Designed by naval architect Siegfried Popper,[47][22] the Tegetthoff-class ships had an overall length of 152 meters (498 ft 8 in), with a beam of 27.90 meters (91 ft 6 in) and a draught of 8.70 meters (28 ft 7 in) at deep load. They were designed to displace 20,000 metric tons (19,684 long tons) at load, but at full combat load they displaced 21,689 metric tons (21,346 long tons).[3] The propellers for the class is where differences in design began to appear between the three ships constructed in Trieste, and Szent István which was constructed in Fiume. The skeg for each propeller shaft on Szent István was a solid, blade-like fitting, unlike the strut-type skegs used in the other three Tegetthoffs.[48] The hull was built with a double bottom, 1.22 meters (4 ft) deep, with a reinforced inner bottom that consisted of two layers of 25-millimeter (1 in) plates. This design was intended by Popper to protect the battleships from naval mines, though it ultimately failed both Szent István and Viribus Unitis when the former was sunk by a torpedo in June 1918 and the latter by a mine in November of that same year.[49] The Tegetthoff class also featured two 2.74-meter (9 ft) Barr and Stroud optical rangefinder posts on both the starboard and port sides for the secondary guns of each ship. These rangefinders were equipped with an armored cupola, which housed an 8-millimeter (0.31 in) Schwarzlose M.07/12 anti-aircraft machine gun.[3]

Szent István had a few external variations from the other ships of her class. These differences included a platform built around the fore funnel which extended from the bridge of the ship to the after funnel upon which several searchlights were installed. A further distinguishing feature was the modified ventilator trunk in front of the mainmast. The rangefinders on Szent István had an armored stand which turned 90° to the right of those on the other three ships. This was done in order to present a smaller target for the ship's broadside.[3] Perhaps the most-notable distinguishing characteristic of Szent István was that she was the only ship of her class not to be fitted with torpedo nets.[3] The other three ships of the Tegetthoff class had their torpedo nets removed in June 1917.[33] The Tegetthoff-class ships were manned by a crew of 1,087 officers and men.[3]

Propulsion

Differences between the three battleships constructed in Trieste and the one in Fiume were most apparent when examining each ship's propulsion. Szent István differed from the other ships in that she possessed two shafts and two Parsons steam turbines, while the propulsion of Viribus Unitis, Tegetthoff, and Prinz Eugen each had four. These turbines were housed in a separate engine-room and powered by twelve Babcock & Wilcox boilers. They were designed to produce a total of 26,400 or 27,000 shaft horsepower (19,686 or 20,134 kW), which was theoretically enough to attain a maximum designed speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph). While it was reported during the speed trials of Tegetthoff that she attained a top speed of 19.75 knots (36.58 km/h; 22.73 mph),[50] the actual top speed of the Tegetthoff-class ships is unknown as the sea trial data and records for each ship were lost after the war.[3] Each ship also carried 1,844.5 metric tons (1,815.4 long tons) of coal, and an additional 267.2 metric tons (263 long tons) of fuel oil that was to be sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate.[3] At full capacity, the Tegetthoffs could steam for 4,200 nautical miles (7,800 km; 4,800 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[8]

Armament

Constructed at the Škoda Works in Plzeň, Bohemia, the Tegetthoffs' main battery consisted of twelve 45-calibre 30.5-centimeter (12 in) Škoda K10 guns mounted in four triple turrets. Two turrets each were mounted forward and aft of the main superstructure in a superfiring pair. The implementation of triple turrets came about for two reasons: the need to ensure the ships had a more compact design and smaller displacement to conform to Austro-Hungarian naval doctrine and budget constraints, and to counter the implementation of triple turrets on the Italian Dante Alighieri.[51] While the Italians had initiated construction on Dante Alighieri before work had begun on the Tegetthoff class, the shipyards in Trieste were able to construct Viribus Unitis faster than their Italian counterparts and she was commissioned in December 1912, just a month before Dante Alighieri. This made the Tegetthoffs the first dreadnoughts in the world with triple turrets, in which the Austro-Hungarian Navy took great pride.[52]

Having three guns on each turret rather than two made it possible to deliver a heavier broadside than other dreadnoughts of a similar size and meant a shorter citadel and better weight distribution. The choice of implementing triple turrets also assisted in the construction speed of the first two ships, as the guns were available at short notice because Škoda had already been working on a triple-turret design ordered by the Imperial Russian Navy when their initial order for the Tegetthoff class arrived.[53]

The Tegetthoffs carried a secondary armament which consisted of a dozen 50-calibre 15-centimeter (5.9 in) Škoda K10 guns mounted in casemates amidships. Additionally, eighteen 50-calibre 7-centimeter (2.8 in) Škoda K10 guns were mounted on open pivot mounts on the upper deck, above the casemates. Three more 7-centimeter (2.8 in) Škoda K10 guns were mounted on the upper turrets for anti-aircraft duties. Two additional 8-millimeter (0.31 in) Schwarzlose M.07/12 anti-aircraft machine guns were mounted atop the armoured cupolas of each ship's rangefinders. Each ship had two 7-centimeter (2.8 in) Škoda G. L/18 landing guns, and two 47-millimeter (1.9 in) Škoda SFK L/44 S guns for use against small and fast vessels such as torpedo boats and submarines. Each ship was also fitted with four 533-millimeter (21 in) submerged torpedo tubes, one each in the bow, the stern, and each side. Each ship usually carried twelve torpedoes.[3]

Armor

The Tegetthoff-class ships were protected at the waterline with an armor belt which measured 280 millimeters (11 in) thick in the central citadel, where the most important parts of the ship were located. This armor belt was located between the midpoints of the fore and aft barbettes, and thinned to 150 millimeters (5.9 in) further towards the bow and stern, but did not reach either. It was continued to the bow by a small patch of 110–130-millimeter (4–5 in) armor. The upper armor belt had a maximum thickness of 180 millimeters (7.1 in), but it thinned to 110 millimeters (4.3 in) from the forward barbette all the way to the bow. The casemate armor was also 180 millimeters (7.1 in) thick.[54]

The sides of the main gun turrets, barbettes, and main conning tower were protected by 280 millimeters (11 in) of armor, except for the turret and conning tower roofs which were 60 to 150 millimeters (2 to 6 in) thick. The thickness of the decks ranged from 30 to 48 millimeters (1 to 2 in) in two layers. The underwater protection system consisted of the extension of the double-bottom upwards to the lower edge of the waterline armor belt, with a thin 10-millimeter (0.4 in) plate acting as the outermost bulkhead. It was backed by a torpedo bulkhead that consisted of two 25-millimeter (1 in) plates.[54] The total thickness of this system was only 1.60 meters (5 ft 3 in), which made it incapable of containing a torpedo warhead detonation or mine explosion without rupturing.[55]

In the spring of 1909, Montecuccoli sent an officer from the Naval Section of the War Ministry to Berlin in order to obtain input from Alfred von Tirpitz on the design of the Tegetthoff class. The Imperial German Navy had conducted gunnery and torpedo tests and concluded that, "The angle between [the] armored deck and belt armor should be as flat as possible", and that "The armored torpedo bulkhead should be angled inwards, the second longitudinal bulkhead outwards. The distance of the torpedo bulkhead from the outer plating should be raised from 2.5 to 4 meters."[56] While Popper adopted several of Tirpitz's suggestions regarding the external layout of the belt armor for the Tegetthoff class, the internal modifications put forward by the Imperial German Navy were not implemented.[57]

Assessment

Although smaller than the contemporary dreadnought and super-dreadnought battleships of the German Kaiserliche Marine and the British Royal Navy, the Tegetthoff class was the first of its type in the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas.[4] The Tegetthoffs were described by former Austro-Hungarian naval officer Anthony Sokol in his book The Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy as "excellent ships", and were acknowledged as some of the most powerful of their type in the region. Their design signaled a change in Austro-Hungarian naval policy, as the ships were capable of far more than coastal defense or patrolling the Adriatic Sea.[4] The Tegetthoffs were so well received that when the time came to plan for the replacement of Austria-Hungary's old Monarch-class coastal defense ships, the navy elected to simply take the layout of the Tegetthoff class and enlarge them to have a slightly greater tonnage and larger main guns.[58]

Despite these praises, criticisms of the Tegetthoff-class design exist. Friedrich Prasky refers to the ships in his article The Viribus Unitis class "The ships were too small and had a very low range of stability."[6] Erwin Sieche writes in his article S.M.S. Szent István: Hungaria's Only and Ill-Fated Dreadnought "There had been much quibbling about the bad design of the Tegetthoff class and the bad workmanship and riveting of the Szent István in particular."[48] Poor riveting has been blamed for the sinking of Szent István,[59][6] and Karl Mohl, chief non-commissioned officer of Szent István's machinery, reported that the rivets from the ships snapped loose during the battleship's sinking.[48] Furthermore, reports emerged following the ship's gunnery trials of rivets in the double bottom of the hull being blown out of their sockets.[60] The sinking of Szent István revealed several flaws in the design of the ships' armor. The naval commission investigating the loss of the battleship ultimately concluded: "The distance between mine armor and 15-cm-ammunition magazines is too small and a major design failure, which most probably caused the widening of the leak."[55] Following Szent István's sinking, it was also discovered that her propeller shafts had such a high degree of resistance that the ship's rudder could only be laid at a maximum angle of 10° at full speed or else she would suffer from a heavy list.[48]

Ships

| Name | Namesake | Builder | Laid down | Launched | Commissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viribus Unitis | "With United Forces" (personal motto of Emperor Franz Joseph I) |

Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Trieste | 24 July 1910 | 24 June 1911 | 6 October 1912 | Transferred to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs on 31 October 1918 Sunk by Italian frogmen on 1 November 1918 |

| Tegetthoff | Vizeadmiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff | 24 September 1910 | 21 March 1912 | 14 July 1913 | Ceded to Italy in 1920 Broken up at La Spezia between 1924 and 1925 | |

| Prinz Eugen | Prince Eugene of Savoy | 16 January 1912 | 30 November 1912 | 8 July 1914 | Ceded to France in 1920 Sunk as target ship in 1922 | |

| Szent István | Szent István király (King Stephen I of Hungary) | Ganz-Danubius, Fiume | 29 January 1912 | 17 January 1914 | 13 December 1915 | Torpedoed and sunk by an Italian torpedo boat on 10 June 1918 |

Construction

Secrecy

Montecuccoli's plans for the battleships gained approval from Emperor Franz Joseph I in January 1909, and by April plans for the ships' design, construction, and financing in the face of the ongoing budget crisis in Budapest were already being laid out.[30] Upon learning that Austria-Hungary was planning or currently building a class of dreadnoughts, the British Admiralty considered the project "as a concealed addition to the German fleet" and interpreted the ships as Austria-Hungary's way of repaying Germany for her diplomatic support during the former's annexation of Bosnia in 1908.[61] During the spring and summer of 1909, the United Kingdom was locked in a heated naval arms race with Germany which led the Royal Navy to look upon the Austro-Hungarian ships as a ploy by German Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz to outpace British naval construction, rather than the latest development in Austria-Hungary's own naval arms race with Italy. The Admiralty's concerns regarding the true purpose of the ships were so great that a British spy was dispatched to Berlin when Montecuccoli sent the officer to obtain recommendations from Tirpitz regarding the design and layout of the Tegetthoff-class ships.[62]

These concerns continued to grow and in April 1909 British Ambassador Fairfax Leighton Cartwright asked Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Alois Lexa von Aehrenthal about the rumored battleships. Aehrenthal denied the construction of the Tegetthoff class, but admitted that plans to construct a class of dreadnoughts were being considered. In an attempt to assure Cartwright that Austria-Hungary was not constructing any ships for the German Navy, Aehrenthal justified any naval expansion as being necessary to secure Austria-Hungary's strategic interests in the Mediterranean. At the time, the potential of Austria-Hungary constructing four dreadnought battleships was widely regarded among the British press, public, and politicians as a provocation on the part of Germany.[63] Neither the Admiralty's suspicions, nor those of some politicians, managed to convince the British Parliament that the German government was attempting to use the Tegetthoff class to escalate Germany and Britain's already contentious naval arms race. When Winston Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911, he rejected any potential Austro-German collusion regarding the battleships.[64]

For a full year, the Austro-Hungarian Navy attempted to keep the project a state secret. This did not prevent rumors about their construction of a series of dreadnought battleships from circulating across Europe. The French Naval Attaché in Vienna complained to Paris in 1910 of extensive secrecy within the Austro-Hungarian Navy, which manifested itself in several ways. Among these were a ban on photography at Pola, future home port of the Tegetthoff class, and near-constant observation by the Austro-Hungarian police.[65] Roughly a year after the project began, the Arbeiter-Zeitung, the Austrian Social Democratic Party newspaper, reported the details of the battleships to the general public.[66] The Christian Social Party, supportive of the construction of the ships and operating on the advice of the navy, published in its own newspaper, Reichspost, that the secret dreadnought project and related financial agreements were true. The Reichpost lobbied in support of the project, citing Austria-Hungary's national security concerns with an Italian dreadnought already under construction. When the story broke Archduke Ferdinand also worked to build public support for the battleships, and the small but growing Austrian Navy League did the same.[22][67]

Assembly

The first ship of the Tegetthoff class, Viribus Unitis, was formally laid down on 23 July 1910. Originally referred to as "Battleship IV", her keel was laid down after months of fiscal and political uncertainty. Two months later Tegetthoff was laid down on 24 September 1910. The title ship of the class, Tegetthoff, was named after Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, a 19th-century Austrian naval admiral known for his 1866 victory over Italy at the Battle of Lissa. She was laid down once it became clear that Vienna and Budapest would pass the necessary budget funding to pay for the construction of the entire class.[43][22]

By the end of 1910, construction on the Tegetthoff-class ships was well underway. Two ships were being assembled in Trieste's slipways, and more were in preparation. Aside from a brief strike in May 1911, construction on the battleships continued at a fast pace.[68][8] Less than a year after being laid down in Trieste, Viribus Unitis was launched on 24 June 1911 at a large ceremony featuring Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the Austrian Minister of War, General Moritz von Auffenberg. Viribus Unitis's sponsor at the ceremony was Archduchess Maria Annunziata, sister to Franz Ferdinand.[69] Seven months later, Prinz Eugen was laid down on 16 January 1912. She was followed by Szent István on 29 January. Tegetthoff was launched on 21 March following delays due to poor weather around Trieste.[8][70] Despite strikes in August 1912 and March 1913 by mechanics working on her engines,[71] Prinz Eugen was launched on 30 November, while construction on Szent István took longer due to the fact that the shipyards in Fiume had to be expanded for a ship of her size. She was launched two years later on 17 January 1914.[72][8]

While the battleships were under construction, discussions began over what to name them. The Naval Section of the War Ministry initially proposed naming the four battleships Tegetthoff, Prinz Eugen, Don Juan, and Hunyadi. Newspapers within Austria reported during construction that one of the ships was to be named Kaiser Franz Joseph I, though it was later revealed the navy had no intentions of renaming the cruiser which already bore the Emperor's name. Archduke Franz Ferdinand proposed Laudon for the fourth ship in honor of the Austrian field marshall. Emperor Franz Joseph I ultimately decided the names of the dreadnoughts, choosing to name the first ship using his own personal motto, Viribus Unitis (Latin: "With United Forces"), while the fourth ship in the class would be named Szent István after the Hungarian king and saint, Stephen I.[2]

Commissioning

When Viribus Unitis was commissioned on 6 October 1912,[71] she was at the time the most expensive warship ever to be constructed. The Italian Dante Alighieri had been laid down before Viribus Unitis but was not commissioned until January 1913. This meant Austria-Hungary became the sixth nation, after the United Kingdom, Germany, Brazil, the United States, and Japan to possess a dreadnought battleship.[46][lower-alpha 5] Montecuccoli addressed the Austrian and Hungarian Parliaments on 15 October 1912 and laid out his vision for the role the Tegetthoff class would play in naval policy. Declaring that Austria-Hungary had become "a Mediterranean power" in light of her new dreadnoughts,[73] Montecuccoli expected that the new class of battleships would help Austria-Hungary "assume our proper place among the Mediterranean powers".[74]

Viribus Unitis was soon followed by Tegetthoff, the namesake of the class, on 14 July 1913.[8] During her gunnery trials, a discharge from one of the main guns of Tegetthoff damaged the staterooms of the ship's officers.[75] Prinz Eugen was commissioned on 8 July 1914, ten days after Archduke Franz Ferdinand's assassination in Sarajevo.[8] Expansion of the Graz-Danubius shipyards in Fiume delayed the launching and christening of Szent István until 17 January 1914. Though it was customary for either the Emperor or his heir to be present at the launching of a major warship, Franz Joseph was too feeble and his heir, Franz Ferdinand, refused to be there due to his anti-Hungarian attitudes. Franz Joseph sent a telegram of congratulations to avoid controversy, and the ceremony was presided over by Archduchess Maria Theresa who launched it with the words: "Slip out and may the protection of the Almighty be with you on all your ways!"[2] Also present at the ceremony was Hungarian Prime Minister Tisza, Minister of Finance János Teleszky, and Minister to the Imperial Court Stephan Burián von Rajecz. As the German cruiser Breslau had recently been refitted at Trieste, her officers also attended the ceremony.[2]

During the launching itself there was an accident when the starboard anchor had to be dropped to prevent the ship from hitting a ship carrying spectators of the celebrations, but the anchor chain had not been shackled to the ship and it struck two dockworkers, killing one and crushing the left leg of the other. The following day, the navy had to raise the anchor out of 48 meters (157 ft) of water and re-attach it to the ship.[76] Her fitting out was further delayed by the start of World War I six months later, and she was commissioned as the final battleship of the Tegetthoff class on 13 December 1915.[3]

History

Pre-war

Prior to World War I, the Tegetthoff class served as the pride of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, conducting several voyages throughout the Adriatic and Mediterranean Seas as members of the 1st Battle Division under the command of Vice-Admiral Maximilian Njegovan.[77] In the spring of 1914 Viribus Unitis and Tegetthoff, together with Zrínyi and the coastal defense ship Monarch, traveled the eastern Mediterranean, the Sea of Sicily, and the Levant, visiting the ports of Smyrna, Beirut, Alexandria, and Malta.[78][77][79] While at port in Alexandria, two of Monarch's crew contracted smallpox and cerebrospinal meningitis which caused the ship to be quarantined for several weeks in Pola.[80] Meanwhile, Viribus Unitis and Tegetthoff arrived at Malta on 22 May, before leaving for Pola on 28 May.[81][77] Upon their return, Viribus Unitis was tasked with transporting Ferdinand to the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to watch military maneuvers. Following the maneuvers, Ferdinand and his wife Sophie planned to visit Sarajevo to open the state museum in its new premises.[82] On 24 June the battleship brought the Archduke from Trieste to the Narenta River, where he boarded a yacht which took him north towards Sarajevo. After observing the military maneuvers for three days, the Archduke met his wife in Sarajevo. On 28 June 1914, they were shot to death by Gavrilo Princip.[83]

Upon hearing of the assassination, Commander-in-Chief of the Navy Anton Haus sailed south from Pola with an escort fleet comprising Tegetthoff, the scout cruiser Admiral Spaun, and several torpedo boats. Two days after their murders, Ferdinand and Sophia's bodies were transferred aboard Viribus Unitis, which had been anchored waiting to receive the Archduke for his return, and were transported back to Trieste.[84] Viribus Unitis was shadowed by Haus' escort fleet for the journey, with the fleet moving slowly along the Dalmatian coast, usually within sight of land. Coastal towns and villages rang church bells when the ships passed while spectators watched the fleet from the shoreline.[77] The Archduke's death triggered the July Crisis, culminating in Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on the Kingdom of Serbia on 28 July 1914.[85][86]

Outbreak of war

Events unfolded rapidly in the ensuing days. On 30 July 1914 Russia declared full mobilization in response to Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia. Austria-Hungary declared full mobilization the next day. On 1 August both Germany and France ordered full mobilization and Germany declared war on Russia in support of Austria-Hungary. While relations between Austria-Hungary and Italy had improved greatly in the two years following the 1912 renewal of the Triple Alliance,[87] increased Austro-Hungarian naval spending, political disputes over influence in Albania, and Italian concerns over the potential annexation of land in the Kingdom of Montenegro caused the relationship between the two allies to falter in the months leading up to the war.[88] Italy's 1 August declaration of neutrality in the war dashed Austro-Hungarian hopes to use the ships of the Tegetthoff class in major combat operations in the Mediterranean, as the navy had been relying upon coal stored in Italian ports to operate in conjunction with the Regia Marina. By 4 August Germany had already occupied Luxembourg and invaded Belgium after declaring war on France, and the United Kingdom had declared war on Germany in support of Belgian neutrality.[89]

The assistance of the Austro-Hungarian fleet was called upon by the German Mediterranean Division, which consisted of the battlecruiser Goeben and Breslau.[90] The German ships were attempting to break out of Messina, where they had been taking on coal prior to the outbreak of war. By the first week of August, British ships had begun to assemble off Messina in an attempt to trap the Germans. While Austria-Hungary had not yet fully mobilized its fleet, a force was assembled to assist the German ships. This consisted of the three Radetzkys and the three Tegetthoffs, along with the armored cruiser Sankt Georg, Admiral Spaun, six destroyers, and 13 torpedo boats.[91] The Austro-Hungarian high command, wary of instigating war with Great Britain, ordered the fleet to avoid the British ships and to only support the Germans openly while they were in Austro-Hungarian waters. On 7 August, when the Germans broke out of Messina, the Austro-Hungarian fleet had begun to sail for Brindisi to link up with the Germans and escort their ships to a friendly port in Austria-Hungary. However, the German movement toward the mouth of the Adriatic had been a diversion to throw the British and French off their pursuit, and the German ships instead rounded the southern tip of Greece and made their way to the Dardanelles, where they would eventually be sold to the Ottoman Empire. Rather than follow the German ships towards the Black Sea, the Austrian fleet returned to Pola.[11][92]

1914–1915

Following France and Britain's declarations of war on Austria-Hungary on 11 and 12 August respectively, the French Admiral Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère was issued orders to close off Austro-Hungarian shipping at the entrance to the Adriatic Sea and to engage any Austro-Hungarian ships his Anglo-French fleet came across. Lapeyrère chose to attack the Austro-Hungarian ships blockading Montenegro. The ensuing Battle of Antivari ended Austria-Hungary's blockade, and effectively placed the entrance of the Adriatic Sea firmly in the hands of Britain and France.[93][94]

After the breakout of Goeben and Breslau, the ships of the Tegetthoff class saw very little action, spending much of their time in their base at Pola. The navy's general inactivity was partly caused by a fear of mines in the Adriatic.[95] Other factors contributed to the lack of naval activity among the ships of the Tegetthoff class in the first year of the war. Haus was fearful that direct confrontation with the French Navy, even if it should be successful, would weaken the Austro-Hungarian Navy to the point that Italy would have a free hand in the Adriatic.[96] This concern was so great to Haus that he wrote in September 1914, "So long as the possibility exists that Italy will declare war against us, I consider it my first duty to keep our fleet intact."[97] Haus' decision to use the Austro-Hungarian Navy as a fleet in being earned sharp criticism from the Austro-Hungarian Army, the German Navy, and the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry,[98] but it also led to a far greater number of Entente naval forces being devoted to the Mediterranean and the Strait of Otranto. These could have been used elsewhere, such as against the Ottoman Empire during the Gallipoli Campaign.[99]

The most important factor contributing to the Tegetthoffs spending most of their time at port may have been the lack of coal. Prior to the war, the United Kingdom had served as Austria-Hungary's primary source for coal. In the years before the war an increasing percentage of coal had come from mines in Germany, Virginia in the United States, and from domestic sources, but 75% of the coal purchased for the Austro-Hungarian Navy came from Britain. The outbreak of war meant that these sources, as well as those from Virginia, would no longer be available. Significant quantities of coal had been stockpiled before the war however, ensuring the navy was capable of sailing out of port if need be. Even so, the necessity of ensuring the navy's most important ships such as the Tegetthoffs had the coal they needed in the event of an Italian or French attack or a major offensive operation resulted in the dreadnoughts remaining at port unless circumstances necessitated their deployment at sea.[98][95]

In early 1915 Germany suggested that the Austro-Hungarian Navy conduct an attack on the Otranto Barrage in order to relieve pressure on the Ottoman Empire at the height of the Gallipoli Campaign. Haus rejected the proposal, countering that the French had pulled back their blockade to the southernmost end of the Adriatic Sea, and that none of the Anglo-French ships assigned to blockading the strait had been diverted to the Dardanelles.[100]

Haus also advocated strongly in favor of keeping his battleships, in particular the ships of the Tegetthoff class, in reserve in the event of Italy's entry into the war on the side of the Entente. Haus believed that Italy would inevitably break her alliance with Austria-Hungary and Germany, and that by keeping Austria-Hungary's battleships safe, they could rapidly be employed against Italy. This strategy enabled Austria-Hungary's battleships to engage the Italians shortly after Italy's declaration of war in May 1915.[101]

Bombardment of Ancona

After failed negotiations with Germany and Austria-Hungary over Italy joining the war as a member of the Central Powers, the Italians negotiated with the Triple Entente for Italy's eventual entry into the war on their side in the Treaty of London, signed on 26 April 1915.[102] On 4 May Italy formally renounced her alliance to Germany and Austria-Hungary, giving the Austro-Hungarians advanced warning that Italy was preparing to go to war against them. On 20 May, Emperor Franz Joseph I gave the Austro-Hungarian Navy authorization to attack Italian ships convoying troops in the Adriatic or sending supplies to Montenegro. Haus meanwhile made preparations for his most valuable battleships to sortie out into the Adriatic in a massive strike against the Italians the moment war was declared. On 23 May 1915, between two and four hours after the Italian declaration of war reached the main Austro-Hungarian naval base at Pola,[lower-alpha 6] the Austro-Hungarian fleet, including the three ships of the Tegetthoff class, departed to bombard the Italian coast.[95][103]

While several ships bombarded secondary targets and others were deployed to the south to screen for Italian ships that could be steaming north from Taranto, the core of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, spearheaded by the ships of the Tegetthoff class, made their way to Ancona. The bombardment across the province of Ancona was a major success for the Austro-Hungarian Navy. In the port of Ancona an Italian steamer was destroyed and three others damaged. An Italian destroyer, Turbine, was sunk further south. The infrastructure of the port of Ancona and the surrounding towns was severely damaged. The railroad yard and port facilities in the city were damaged or destroyed, while local shore batteries defending them were knocked out. Multiple wharves, warehouses, oil tanks, radio stations, and coal and oil stores were set on fire by the bombardment, and the city's electricity, gas, and telephone lines were severed. Within the city itself, Ancona's police headquarters, army barracks, military hospital, sugar refinery, and Bank of Italy offices all saw damage. 30 Italian soldiers and 38 civilians were killed, while an additional 150 were wounded in the attack.[104][105]

The Austro-Hungarian ships would later move on to bombard the coast of Montenegro, without opposition; by the time Italian ships arrived on the scene, the Austro-Hungarians were safely back in Pola.[106] The objective of the bombardment of Ancona was to delay the Italian Army from deploying its forces along the border with Austria-Hungary by destroying critical transportation systems.[103] The surprise attack on Ancona succeeded in delaying the Italian deployment to the Alps for two weeks. This delay gave Austria-Hungary valuable time to strengthen its Italian border and re-deploy some of its troops from the Eastern and Balkan fronts.[107] The bombardment also delivered a severe blow to Italian military and public morale.[108]

1916–1917

Largely unable to engage in major offensive combat operations after the Bombardment of Ancona, the ships were mostly relegated to defending Austria-Hungary's coastline for the next three years.[109] The lack of combat engagements, or even instances where the Tegetthoffs left port, is exemplified by the career of Szent István. The ship was unable to join her sisters in the Bombardment of Ancona and rarely left the safety of the port except for gunnery practice in the nearby Fažana Strait. She only spent 54 days at sea during her 937 days in service and made only a single two-day trip to Pag Island. In total, only 5.7% of her life was spent at sea; and for the rest of the time she swung at anchor in Pola Harbour. Szent István saw so little action and so little time at sea that she was never drydocked to have her bottom cleaned.[110]

In January 1917 Emperor Karl I attended a military conference at Schloss Pless with German Kaiser Wilhelm II and members of the German Army and Navy. Haus, along with members of Austria-Hungary's naval command at Pola, accompanied the Emperor to this conference in order to discuss naval operations in the Adriatic and Mediterranean for 1917. Days after returning from this conference, Grand Admiral Haus died of pneumonia aboard his flagship Viribus Unitis on 8 February 1917. Newly crowned Karl I attended his funeral in Pola.[111]

Despite his death, Haus' strategy of keeping the Austro-Hungarian Navy, and particularly its dreadnoughts, in port continued. By keeping the Tegetthoffs as a fleet in being, the Austro-Hungarian Navy would be able to continue to defend its lengthy coastline from naval bombardment or invasion by sea. The major ports of Trieste and Fiume would also remain protected. Furthermore, Italian ships stationed in Venice were effectively trapped by the positioning of the Austro-Hungarian fleet, preventing them from sailing south to join the bulk of the Entente forces at the Otranto Barrage.[112]

Njegovan was promoted to admiral and appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Navy. With Njegovan appointed to higher office, command of the 1st Battle Division, which consisted of all four Tegetthoff-class ships, fell to Vice-Admiral Anton Willenik. Njegovan had previously voiced frustration watching the dreadnoughts he had commanded under Haus sit idle at port and upon taking command he had some 400,000 tons of coal at his disposal, but he chose to continue the strategy of his predecessor. Despite a change in command of both the Austro-Hungarian Navy and the Empire which it served, there would be no change in strategy regarding the employment of the Tegetthoff class in battle.[113]

Having hardly ever ventured out to port except to conduct gunnery practice for the past two years, the most significant moments the Tegetthoff-class ships saw while moored in Pola were inspections by dignitaries. The first such visit was conducted by Emperor Karl I on 15 December 1916. During this brief visit the Emperor inspected Pola's naval establishments and Szent István.[114] Karl I returned to Pola in June 1917 in the first formal imperial review of the Austro-Hungarian Navy since 1902. This visit was far grander than his previous trip to the naval base, with officers and sailors crowding the decks of their ships at port and the naval ensign of Austria-Hungary flying from every vessel. The Emperor received multiple cheers and salutes from the men at Pola, who had spent the past two years doing little more than shooting down Italian airplanes and airships.[115] The third dignitary visit came during Kaiser Wilhelm II's inspection of Pola's German submarine base on 12 December 1917. During this trip, the German Emperor also took the time to inspect Szent István in similar fashion to his Austro-Hungarian counterpart. Aside from these visits, the only action the port of Pola and the Tegetthoffs were subject to between the Bombardment of Ancona and the summer of 1918 were the more than eighty air raids conducted by the newly formed Italian Air Force.[116]

1918

Following the Cattaro Mutiny in February 1918, Admiral Njegovan was fired as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, though at Njegovan's request it was announced that he was retiring.[20] Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya, commander of Prinz Eugen, was promoted to rear admiral and named Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet. Horthy's promotion was met with support among many members of the naval officer corps, who believed he would use Austria-Hungary's navy to engage the enemy. Horthy's appointment did however pose difficulties. His relatively young age alienated many of the senior officers, and Austria-Hungary's naval traditions included an unspoken rule that no officer could serve at sea under someone of inferior seniority. This meant that the heads of the First and Second Battle Squadrons, as well as the Cruiser Flotilla, all had to go into early retirement.[117]

In March 1918 Horthy's position within the navy was secured, and he had begun to reorganize it according to his own vision, with strong support from Emperor Karl I. By this time, the United States had declared war on both Germany and Austria-Hungary and had begun to send ships to aid the French, British, and Italians in the Mediterranean Sea. Horthy had inherited an "Austrian lake" in the Adriatic Sea, according to the United States Navy,[118] and shipping of supplies, troops, sick and wounded personnel, and military equipment across various ports in the Adriatic was done with little to no opposition from the Allied Powers. American planning for a naval offensive to sweep the Adriatic and even land up to 20,000 marines with naval and infantry support from Britain, France, and Italy were halted by the onset of the German Spring Offensive in France, launched on 21 March 1918.[119] Horthy used these first few months as Commander-in-Chief to finish his re-organization of the navy. As one of Njegovan's final actions before he was ousted entailed shifting several smaller and older vessels around to different ports under Austro-Hungarian control, the only ships which remained at port in Pola aside from the three of the Radetzky class were the four dreadnoughts of the Tegetthoff class, which had now fallen under the command of Captain Heinrich Seitz. Horthy worked to re-locate as many ships as he could back to Pola in order to maximize the threat the Austro-Hungarian Navy posed to the Allied Powers. Horthy also used his appointment to take the Austro-Hungarian fleet out of port for maneuvers and gunnery practice on a regular basis. The size of these operations were the largest the navy had seen since the outbreak of the war.[120]

These gunnery and maneuver practices were conducted not only to restore order in the wake of several failed mutinies, but also to prepare the fleet for a major offensive operation. Horthy's strategic thinking differed from his two predecessors, and shortly after assuming command of the navy he resolved to undertake a major fleet action in order to address low morale and boredom, and make it easier for Austro-Hungarian and German U-boats to break out of the Adriatic into the Mediterranean. After several months of practice, Horthy concluded the fleet was ready for a major offensive at the beginning of June 1918.[121]

Otranto Raid

Horthy was determined to use the fleet to attack the Otranto Barrage. Planning to repeat his successful raid on the blockade in May 1917,[122] Horthy envisioned a massive attack on the Allied forces with his four Tegetthoff-class ships providing the largest component of the assault. They would be accompanied by the three ships of the Erzherzog Karl-class pre-dreadnoughts, the three Novara-class cruisers, the cruiser Admiral Spaun, four Tátra-class destroyers, and four torpedo boats. Submarines and aircraft would also be employed in the operation to hunt down enemy ships on the flanks of the fleet.[123][124][125]

On 8 June 1918 Horthy took his flagship, Viribus Unitis, and Prinz Eugen south with the lead elements of his fleet.[122] On the evening of 9 June, Szent István and Tegetthoff followed along with their own escort ships. Horthy's plan called for Novara and Helgoland to engage the Barrage with the support of the Tátra-class destroyers. Meanwhile, Admiral Spaun and Saida would be escorted by the fleet's four torpedo boats to Otranto to bombard Italian air and naval stations. The German and Austro-Hungarian submarines would be sent to Valona and Brindisi to ambush Italian, French, British, and American warships that sailed out to engage the Austro-Hungarian fleet, while seaplanes from Cattaro would provide air support and screen the ships' advance. The battleships, and in particular the Tegetthoffs, would use their firepower to destroy the Barrage and engage any Allied warships they ran across. Horthy hoped that the inclusion of these ships would prove to be critical in securing a decisive victory.[124]

En route to the harbour at Islana, north of Ragusa, to rendezvous with Viribus Unitis and Prinz Eugen for the coordinated attack on the Otranto Barrage, Szent István and Tegetthoff attempted to make maximum speed in order to catch up to the rest of the fleet. In doing so, Szent István's turbines started to overheat and speed had to be reduced to 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). When an attempt was made to raise more steam in order to increase to 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) Szent István produced an excess of smoke. At about 3:15 am on 10 June,[lower-alpha 7] two Italian MAS boats, MAS-15 and MAS-21, spotted the smoke from the Austrian ships while returning from an uneventful patrol off the Dalmatian coast. The MAS platoon was commanded by Capitano di corvetta Luigi Rizzo, who had sunk the Austro-Hungarian coastal defense ship SMS Wien in Trieste six months before.[126] The individual boats were commanded by Capo timoniere Armando Gori and Guardiamarina di complemento Giuseppe Aonzo respectively. Both boats successfully penetrated the escort screen and split to engage each of the dreadnoughts. MAS-21 attacked Tegetthoff, but her torpedoes failed to hit the ship.[126] MAS-15 fired her two torpedoes successfully at 3:25 am at Szent István. Both boats evaded any pursuit although MAS-15 had to discourage the Austro-Hungarian torpedo boat Tb 76 T by dropping depth charges in her wake. Tegetthoff, thinking that the torpedoes were fired by submarines, pulled out of the formation and started to zigzag to throw off any further attacks. She repeatedly fired on suspected submarine periscopes.[127]

Szent István was hit by two 45-centimeter (18 in) torpedoes abreast her boiler rooms. The aft boiler room quickly flooded and gave the ship a 10° list to starboard. Counterflooding of the portside trim cells and magazines reduced the list to 7°, but efforts to use collision mats to plug the holes failed. While this was going on the dreadnought steered for the nearby Bay of Brgulje at low speed, before eventually coming to a halt in order to provide additional power to the ship's pumps, which could discharge 6,000 metric tons (5,905 long tons) of water per hour. However, water continued to leak into the forward boiler room and eventually doused all but the two boilers on the port side. This killed the power for the pumps and only left enough electricity to run the lights. The turrets were trained to port in a futile effort to counter the list and their ready ammunition was thrown overboard.[127][124] Upon returning to the formation at 4:45 am, Tegetthoff attempted to take Szent István in tow, which failed.[128] Many of the crew members of the sinking battleship assembled on the deck to use their weight along with the turned turrets as a counterbalance, but the ship was taking on too much water, with her watertight bulkheads giving way to the flooding one by one.[60] Szent István's chaplain performed one final blessing while the crew of Tegetthoff emerged onto her decks to salute the sinking ship. At 6:12 am, with the pumps unequal to the task, Szent István capsized off Premuda. 89 sailors and officers died in the sinking, 41 of them from Hungary. The low death toll can be partly attributed to the long amount of time it took for the battleship to sink, and the fact that all sailors with the Austro-Hungarian Navy had to learn to swim before entering active service.[127][124][129] The captain of Szent István, Heinrich Seitz, was prepared to go down with his ship but was saved after being thrown off the bridge when she capsized.[130]

Film footage and photographs exist of Szent István's last half-hour, taken by Linienschiffsleutnant Meusburger of Tegetthoff with his own camera and by an official film crew. The two films were later spliced together and exhibited in the United States after the war.[126] The battleship's sinking was one of only two on the high seas to ever be filmed, the other being that of the British battleship HMS Barham during World War II.[131] Proceeds from the film of Szent István capsizing were eventually used to feed children in Austria following the ending of the war.[126]

Fearing further attacks by torpedo boats or destroyers from the Italian navy, and possible Allied dreadnoughts responding to the scene, Horthy believed the element of surprise had been lost and called off the attack. In reality, the Italian torpedo boats had been on a routine patrol, and Horthy's plan had not been betrayed to the Italians as he had feared. The Italians did not even discover that the Austrian dreadnoughts had departed Pola until 10 June when aerial reconnaissance photos revealed that they were no longer there.[55] Nevertheless, the loss of Szent István and the blow to morale it had on the navy forced Horthy to cancel his plans to assault the Otranto Barrage. The fleet returned to the base at Pola where it would remain for the rest of the war.[129][130]

End of the war

On 17 July 1918, Pola was struck by the largest air raid the city would see during the war. 66 Allied planes dropped over 200 bombs, though none of the Tegetthoffs were hit or damaged in the attack.[132]

By October 1918 it had become clear that Austria-Hungary was facing defeat in the war. With various attempts to quell nationalist sentiments failing, Emperor Karl I decided to sever Austria-Hungary's alliance with Germany and appeal to the Allied Powers in an attempt to preserve the empire from complete collapse. On 26 October Austria-Hungary informed Germany that their alliance was over. In Pola the Austro-Hungarian Navy was in the process of tearing itself apart along ethnic and nationalist lines. Horthy was informed on the morning of 28 October that an armistice was imminent, and used this news to maintain order and prevent a mutiny among the fleet. While a mutiny was avoided, tensions remained high and morale was at an all-time low. The situation was so stressful for members of the navy that the captain of Prinz Eugen, Alexander Milosevic, committed suicide in his quarters aboard the battleship.[133]

On 29 October, the National Council in Zagreb announced Croatia's dynastic ties to Hungary had come to a formal conclusion. The National Council also called for Croatia and Dalmatia to be unified, with Slovene and Bosnian organizations pledging their loyalty to the newly formed government. This new provisional government, while throwing off Hungarian rule, had not yet declared independence from Austria-Hungary. Thus Emperor Karl I's government in Vienna asked the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs for help maintaining the fleet stationed at Pola and keeping order among the navy. The National Council refused to assist unless the Austro-Hungarian Navy was first placed under its command.[134] Emperor Karl I, still attempting to save the Empire from collapse, agreed to the transfer, provided that the other "nations" which made up Austria-Hungary would be able to claim their fair share of the value of the fleet at a later time.[135] All sailors not of Slovene, Croatian, Bosnian, or Serbian background were placed on leave for the time being, while the officers were given the choice of joining the new navy or retiring.[135][136]

The Austro-Hungarian government thus decided to hand over the bulk of its fleet to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs without a shot being fired. This was considered preferential to handing the fleet to the Allies, as the new state had declared its neutrality. Furthermore, the newly formed state had also not yet publicly dethroned Emperor Karl I, keeping the possibility of reforming the Empire into a triple monarchy alive. The transfer to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs began on the morning of 31 October, with Horthy meeting representatives from the South Slav nationalities aboard his flagship, Viribus Unitis. After "short and cool" negotiations, the arrangements were settled and the handover was completed that afternoon. The Austro-Hungarian Naval Ensign was struck from Viribus Unitis, and was followed by the remaining ships in the harbor. After the transfer, Horthy took with him from his personal cabin a portrait of Emperor Franz Joseph I, which the late Emperor had gifted to the battleship, along with the ceremonial silk ensign of Viribus Unitis, and Horthy's own personal admiral's flag. That evening Viribus Unitis was renamed Jugoslavija.[137] Control over the battleship, and the head of the newly-established navy for the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, fell to Captain Janko Vuković, who was raised to the rank of admiral and took over Horthy's old responsibilities as Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet.[138][136]

On 1 November 1918, the transfer being still unknown to Italy, two men of the Italian Regia Marina, Raffaele Paolucci and Raffaele Rossetti, rode a primitive manned torpedo (nicknamed Mignatta or "leech") into the naval base at Pola. Using limpet mines, they attacked Jugoslavija and the freighter Wien.[139] Traveling down the rows of battleships, the two men encountered Jugoslavija at around 4:40 am. Rossetti placed one canister of TNT on the hull of the battleship, timed to explode at 6:30 am. He then flooded the second canister, sinking it on the harbor floor close to the ship. The men had no breathing sets, and therefore had to keep their heads above water. They were discovered and taken prisoner just after placing the explosives under the battleship's hull. The Italians did not know that the Austrian government had handed over Viribus Unitis, along with most of the Austro-Hungarian fleet, to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. They were taken aboard Jugoslavija, where they informed her new captain of what they had done but did not reveal the exact position of the explosives.[139] Vuković then arranged for the two prisoners to be taken safely to the sister ship Tegetthoff, and ordered the evacuation of the ship.[140] The explosion did not happen at 6:30 am as predicted and Vuković, believing mistakenly that the Italians had lied, returned to the ship with many sailors. When the mines exploded shortly afterwards at 6:44 am, the battleship sank in 15 minutes; Vuković and 300–400 of the crew went down with her. The second explosive canister, lying on the bottom, exploded close to the freighter Wien, resulting in her sinking.[139] The two Italians were interned for a few days until the end of the war and were honored by the Kingdom of Italy with the Gold Medal of Military Valor.[141][142][143][1]

Post-war

The Armistice of Villa Giusti, signed between Italy and Austria-Hungary on 3 November 1918, refused to recognize the transfer of Austria-Hungary's warships to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. As a result, on 4 November 1918, Italian ships sailed into the ports of Trieste, Pola, and Fiume. On 5 November, Italian troops occupied the naval installations at Pola.[144] While the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs attempted to hold onto their ships, they lacked the men and officers to do so as most sailors who were not South Slavs had already gone home. The National Council did not order any men to resist the Italians, but they also condemned Italy's actions as illegitimate. On 9 November, all remaining ships in Pola harbor had the Italian flag raised. At a conference at Corfu, the Allied Powers agreed the transfer of Austria-Hungary's Navy to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs could not be accepted, despite sympathy from the United Kingdom.[145] Faced with the prospect of being given an ultimatum to hand over the former Austro-Hungarian warships, the National Council agreed to hand over the ships beginning on 10 November 1918.[146]

It would not be until 1920 that the final distribution of the ships was settled among the Allied Powers under the terms of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Of the two remaining Tegetthoffs, Prinz Eugen was ceded to France. The French Navy removed the main armament of the battleship for inspection then used the dreadnought as a target ship. She was first subject to test aerial bombardment attacks and later sunk by the battleships Paris, Jean Bart, and France off Toulon on 28 June 1922, exactly eight years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.[147][8] In March 1919, Tegetthoff and Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand, both flying the Italian flag, were escorted into Venice where they were exhibited as war trophies by the Italians. During that time period, Tegetthoff starred in the movie Eroi dei nostri mari ("Heroes of our seas") which depicted the sinking of Szent István. Following the adoption of the Washington Naval Treaty in 1922, she was broken up at La Spezia between 1924 and 1925.[8] The wreck of Viribus Unitis was salvaged from 60 meters (196 ft 10 in) of water in Pola harbor and scrapped between 1920 and 1930.[14]

Legacy

After the war, MAS-15 was installed in the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II as part of the Museo del Risorgimento in Rome for the torpedo boat's role in the sinking of Szent István. The anniversary of the sinking, 10 June, has been celebrated by the Regia Marina, and its successor, the Marina Militare, as the official Italian Navy Day (Italian: Festa della Marina).[131] After Tegetthoff was dismantled, one of her anchors was placed on display at the Monument to Italian Sailors at Brindisi, where it can still be found.[148]

Following the Anschluss of Austria into Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938, Adolf Hitler used Austria-Hungary's naval history to appeal to the Austrian public and obtain their support. Having lived in Vienna during the development of much of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, Hitler decided upon an "Austrian" sounding name for a German cruiser which was being constructed at Kiel.[149] The cruiser was originally to be named Tegetthoff after Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, though concerns over the possible insult to Italy and Benito Mussolini of naming the cruiser after the Austrian victor of the Battle of Lissa, led the Kriegsmarine to adopt Prinz Eugen as the ship's namesake, after the Austrian general Prince Eugene of Savoy.[150] Prinz Eugen had also served as the name for four Austrian naval ships between 1848 and 1918.[151] She was launched on 22 August 1938,[152] in a ceremony attended by Hitler and the Governor (German: Reichsstatthalter) of Ostmark, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, who made the christening speech. Also present at the launch was Regent of Hungary, Admiral Miklós Horthy. Horthy had previously commanded the Tegetthoff-class battleship Prinz Eugen from 24 November 1917 to 1 March 1918 and had commanded the Austro-Hungarian Navy in the final months of World War I. Horthy wife's, Magdolna Purgly, performed the christening.[153] In reference to her originally planned name and in homage to the Austro-Hungarian Navy, the bell from Tegetthoff was presented to the German cruiser Prinz Eugen on 22 November 1942 by the Italian Regia Marina.[154] After World War II, the bell from Tegetthoff was placed on display in Graz, Austria, where it can still be viewed.[155]

The wreck of Szent István was located in the mid-1970s by the Yugoslav Navy. She lies upside down at a depth of 66 meters (217 ft).[156] Her bow broke off when it hit the seabed while the stern was still afloat, but is immediately adjacent to the rest of the heavily encrusted hull. The two holes from the torpedo hits are visible in the side of the ship as is another deep hole which may be from a torpedo fired at Tegetthoff by MAS-21. She is a protected site of the Croatian Ministry of Culture.[157]

Notes

Footnotes

- Viribus Unitis was transferred to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs on 31 October 1918. The next day, the ship was destroyed by an Italian mine while moored at port in Pola. She was owned by the unrecognized state for only one day. Tegetthoff and Prinz Eugen were also handed over to the new state as well, but Italy's occupation of Pola on 5 November prevented their transfer.

- On 5 November, Italian troops occupied Pola and the Italian flag was raised above Tegetthoff and Prinz Eugen on 9 November. Both ships were surrendered to the Allied Powers by the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs on 10 November 1918. Under the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1920, Tegetthoff was ceded to Italy while Prinz Eugen was ceded to France.

- Szent István possessed two shafts and two turbines as opposed to four of each among the other three ships of the Tegetthoff class.

- Official records for the speed trials of all four ships of the Tegetthoff class were lost at the end of the war. It is estimated based on the propulsion of the class that a speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) was attainable. In March 1913 it was reported that Tegetthoff produced a top speed of 19.75 knots (36.58 km/h; 22.73 mph).

- There is some debate over the exact date of the commission of Viribus Unitis and the time it took to construct her. Halpern and Sondhaus state that the battleship was constructed within 27 months and commissioned in October 1912. Sokol states the ship was built in a "record time" of 24 months. Sieche and Preston maintain the ship was constructed in 29 months and was commissioned on 5 December 1912. Vego claims the ship was constructed in 26 months and was commissioned into the fleet on 26 September 1912. Parliamentary reports from the United Kingdom's House of Commons indicates the ship was commissioned on 6 October 1912. For the purposes of this article, the ship's commissioned date is given as 6 October 1912 as it is the most-commonly reported date.

- There are two conflicting times given for when the fleet departed Pola. Halpern states that it was four hours until the fleet set sail while Sokol claims that the fleet left Pola two hours after the declaration reached Admiral Haus.

- Debate exists over what was the exact time when the attack took place. Sieche states that the time was 3:15 am when Szent István was hit while Sokol claims that the time was 3:30 am.

Citations

- Sokol 1968, p. 139.

- Sieche 1991, p. 116.

- Sieche 1991, p. 133.

- Sokol 1968, p. 69.

- Koburger 2001, p. 29.

- Prasky 1978, p. 105.

- Sokol 1968, pp. 150–151.

- Sieche 1985, p. 334.

- Sokol 1968, p. 116.

- Sokol 1968, pp. 105–107.