Three-North Shelter Forest Program

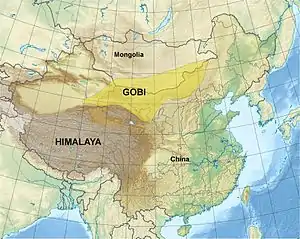

The Three-North Shelter Forest Program (simplified Chinese: 三北防护林; traditional Chinese: 三北防護林; pinyin: Sānběi Fánghùlín), also known as the Three-North Shelterbelt Program, Green Great Wall or Great Green Wall, is a series of human-planted windbreaking forest strips (shelterbelts) in China, designed to hold back the expansion of the Gobi Desert,[1] and provide timber to the local population.[2] The program started in 1978, and is planned to be completed around 2050,[3] at which point it will be 4,500 kilometres (2,800 mi) long.

The project's name indicates that it is to be carried out in all three of the northern regions: the North, the Northeast and the Northwest.[4] This project has historical precedences dating back to before the Common Era. However, in premodern periods, government sponsored afforestation projects along the historical frontier regions were mostly for military fortification.[5]

Effects of the Gobi Desert

China has seen 3,600 km2 (1,400 sq mi) of grassland overtaken every year by the Gobi Desert.[6] Each year, dust storms blow off as much as 2,000 km2 (800 sq mi) of topsoil, and the storms are increasing in severity each year. These storms also have serious agricultural effects for other nearby countries, such as Japan, North Korea, and South Korea.[7] The Green Wall project was begun in 1978, with the proposed end result of raising northern China's forest cover from 5 to 15 percent,[8] thereby reducing desertification.

Methodology and progress

The fourth and most recent phase of the project, started in 2003, has two parts: the use of aerial seeding to cover wide swathes of land where the soil is less arid, and the offering of cash incentives to farmers to plant trees and shrubs in areas that are more arid.[9] A $1.2 billion oversight system (including mapping and surveillance databases) is also to be implemented.[9] The "wall" will have a belt with sand-tolerant vegetation arranged in checkerboard patterns to stabilize the sand dunes. A gravel platform will be next to the vegetation to hold down sand and encourage a soil crust to form.[9] The trees should also serve as a windbreak from dust storms.

Measuring success

As of 2009, China's planted forest covered more than 500,000 square kilometers (increasing tree cover from 12% to 18%) – the largest artificial forest in the world.[10] Of the 53,000 hectares planted that year, a quarter died.[8] In 2008, winter storms destroyed 10% of the new forest stock, causing the World Bank to advise China to focus more on quality rather than quantity in its stock species.[10]

Problems

If the trees succeed in taking root, they could soak up large amounts of groundwater, which would be extremely problematic for arid regions like northern China.[9] For example, in Minqin, an area in north-western China, studies showed that groundwater levels have dropped by 12–19 metres since the advent of the project.[8]

Land erosion and overfarming have halted planting in many areas of the project. China's increasing levels of pollution has also weakened the soil, causing it to be unusable in many areas.[6]

Furthermore, planting blocks of fast-growing trees reduces the biodiversity of forested areas, creating areas that are not suitable to plants and animals normally found in forests. "China plants more trees than the rest of the world combined", says John McKinnon, the head of the EU-China Biodiversity Programme. "But the trouble is they tend to be monoculture plantations. They are not places where birds want to live." The lack of diversity also makes the trees more susceptible to disease, as in 2000, when one billion poplar trees were lost to disease, setting back 20 years of planting efforts.[8]

Liu Tuo, head of the desertification control office in the state forestry administration, is of the opinion that there are huge gaps in the country's efforts to reclaim the land that has become desert.[11] At present there are around 1.73 million sq kilometers that have become desert in China, of which 530,000 km2 are treatable. But at the present rate of treating 1,717 km2 per year, it would take 300 years to reclaim the land that has become desert.[12]

Relations to climate change

China's forest scientists argued that monoculture tree plantations are more effective at absorbing the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide than slow-growth forests,[10] so while diversity may be lower, the trees purportedly help to offset China's carbon emissions. However, a study released in 2016 finds that wild woodlands are much more effective than monocultural forests in storing carbon dioxide, with more resilient and greater tree health, size, lifespan, and depth of organic matter rich soil.[13]

Criticism

Gao Yuchuan, the Forest Bureau head of Jingbian County, Shanxi, stated that "planting for 10 years is not as good as enclosure for one year", referring to the alternative non-invasive restoration technique that fences off (encloses) a degraded area for two years to allow the land to restore itself.[8] Jiang Gaoming, an ecologist from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and proponent of enclosure, says that "planting trees in arid and semi-arid land violates [ecological] principles".[8] The worry is that the fragile land cannot support such massive, forced growth. Others worry that China is not doing enough on the social level. To succeed, many believe the government should encourage farmers financially to reduce livestock numbers or relocate away from arid areas.[9]

See also

References

- "Media Reports: China's Great Green Wall". BBC News. 3 March 2001. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- "Three-North Shelterbelt Poplar Tree Death Caused by the Director of the State Forestry Bureau" (in Chinese). Phoenix TV. Archived from the original on 2019-07-23. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- "State Forestry Administration" (in Chinese). English.forestry.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 2014-03-15. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- 李谷城 (Li Kwok-sing) (2006). 中國大陸改革開放新詞語 中國大陸改革開放新詞語 [A Glossary of New Political Terms of the PRC in the Post-Reform Era] (in Chinese). HK: Chinese University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-962-996-258-6.

- Chen, Yuan Julian (2018). "Frontier, Fortification, and Forestation: Defensive Woodland on the Song–Liao Border in the Long Eleventh Century". Journal of Chinese History. 2 (2): 313–334. doi:10.1017/jch.2018.7. ISSN 2059-1632.

- "The Fall of the Green Wall of China". WorldChanging. 29 December 2003. Archived from the original on 19 July 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- "China's Dust Storms Raise Fears of Impending Catastrophe". National Geographic. 1 June 2001. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- "China's Great Green Wall Proves Hollow". The Epoch Times. 29 July 2009. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- "The Green Wall Of China". Wired. April 2003. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- Watts, Jonathan (11 March 2009). "China's loggers down chainsaws in attempt to regrow forests". London: The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- Jonathan Watts (4 January 2011). "China makes gain in battle against desertification but has long fight ahead | Environment". London: The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- Patience, Martin (2011-01-04). "BBC News - China official warns of 300-year desertification fight". Bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2011-09-20. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- McGrath, Matt (9 February 2016). "'Wrong type of trees' in Europe increased global warming". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.