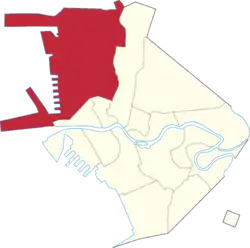

Tondo, Manila

Tondo is a district located in Manila, Philippines. It is the largest in terms of area and population of Manila's sixteen districts,[2] with a Census-estimated 631,313 people in 2015 and consists of two congressional districts. It is also the most densely populated district in the city.

Tondo | |

|---|---|

Recto Avenue running through Divisoria. | |

| |

| Country | Philippines |

| Region | National Capital Region |

| City | Manila |

| Congressional District | 1st and 2nd districts of Manila |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8.65 km2 (3.40 sq mi) |

| Population (2015)[1] | |

| • Total | 631,363 |

| • Density | 73,000/km2 (190,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (Philippine Standard Time) |

History

Etymology

The name Tondo derives from Tundun, the Old Tagalog name of the city in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription of 900AD (see below), the earliest native document found within the Philippines. Postma, the first to translate the copperplate, believes the term tundun originated from the old Indian language Sanskrit,[3] which was used alongside Old Malay as a language of politics and religion in the area at the time. Before this landmark discovery, several theories (however incorrect now) existed:

Philippine National Artist Nick Joaquin suggested that it might be a reference to high ground ("tundok").[4] French linguist Jean-Paul Potet, however supposed that the River Mangrove, Aegiceras corniculatum, which at the time was called "tundok" ("tinduk-tindukan" today), was the most likely origin of the name.[5]

Tondo in early Philippine history

The region of Tondo has been settled by humans for over 1,100 years. Historically, Tondo already existed in the year 900 AD according to the Laguna Copperplate Inscription,[6] a legal document that is the earliest document in the Philippines, written in Kawi now housed in the National Museum of Anthropology. According to this document, Tondo was ruled by an unnamed person who held the Sanskrit title of senapati or the equivalent of an admiral. Tondo also had influence all the way to the modern-day province of Bulacan particularly around Lihan (Malolos) and Gatbuca (Calumpit).

Tondo was ruled by a line of lakan until the Spanish conquest.

Colonial Period

After the Spaniards conquered Tondo in January 1571 they established the Province of Tondo which covered many territories in Northern Luzon particularly Pampanga, Bulacan and Rizal (formerly called Morong), with the city of Manila as its center. In census conducted by Miguel de Loarca in 1583 Tondo was reported to have spoken the same language as the natives of the province of Pampanga.[7] Institute of National Language commissioner Jose Villa Panganiban also wrote that the dividing line between Kapampangan and Tagalog was the Pasig River, and that Tondo therefore originally spoke Kapampangan.[8] although Fray Isacio Rodriquez's Historia dela Provincia del Santisimo Nombre de Jesus de Filipinas stated that Provincia de Tagalos which is Tondo covers all the territories of the future Archdiocese of Manila. Prior to the establishment of the Province of Bulacan in 1578 Malolos and Calumpit were also included in the territory of Tondo as its visitas. In 1800, the Province of Tondo was renamed to Province of Manila.

Tondo was one of the first provinces to declare rebellion against Spain in year 1896. In 1911, under the American colonial regime, there was a major reorganization of political divisions, and the province of Tondo was dissolved, and its towns given to the provinces of Rizal and Bulacan. Today, Tondo just exists as a district in the City of Manila.

Contemporary period

Slums developed in Tondo along the Pasig River. Authorities sought to improve housing conditions on these areas without condoning the action of squatting committed by the slums' residents. In the 1970s, the World Bank provided funds to improve conditions in Tondo which led the increase of rent prices and a property boom in the area. These caused the poor to be marginalized. The slums that were upgraded were legalized but these areas remain vastly different from other parts of Manila with higher population density, more irregular road and plot patterns, and uncontrolled housing.[9] In the 1987 constitution, Tondo split into two congressional districts of Manila making the first district to the west while the second district in the east. Paco also split by fifth and sixth congressional districts which the fifth in the south and sixth in the north.

Economy

Tondo hosts the Manila North Harbor Port, the northern half of the Port of Manila, the primary seaport serving Metro Manila and surrounding areas.[10]

The area also hosted Smokey Mountain, a landfill which served Metro Manila and employed thousands of people from around 1960 until its closure in the late 1990s. The dumpsite served as a symbol of poverty even at least two decades since its closure.[11]

Demographics

Urbanization as well as the Lina Law which favors squatters over land owners has resulted in Tondo being one of the most densely populated areas in the world at 69,000 inhabitants per square kilometer (180,000/sq mi).[12]

Crime

Tondo has developed a reputation for criminality and poverty. In 2010, Manila records state that Tondo has the highest criminal rate in the whole city with the most common crime being pick pocketing.[13]

Culture

The district celebrates the feast of the Santo Niño de Tondo annually in January, which is dedicated to the image of the Santo Niño housed within the 16th century Augustinian Tondo Church. The Lakbayaw Street Dance Festival, a competition among Ati-Atihan groups and school, local and religious groups, served as the climax of the feast.[14]

Education

The Manila office of the Department of Education lists 26 public elementary schools and 11 public high schools in Tondo.[15]

Notable people

- Andrés Bonifacio (November 30, 1863 – May 10, 1897), a Filipino revolutionary leader and the president of the Tagalog Republic

- Lakandula or Lakan Dula (1503–1575), the last ruler of pre-colonial Tondo when the Spaniards first conquered the lands of the Pasig River delta in the Philippines in the 1570s

- Isko Moreno, actor and the current mayor of Manila

- Manny Villar, businessmen, chairman Vista Land, former president of the Senate of the Philippines

- Ramon Ang, businessman, vice-chairman of San Miguel Corporation

- Arnold Clavio, newscaster and journalist

- Rene Requiestas (1957–1993), actor-comedian

- RK Bagatsing, actor-model

- Vice Ganda, actor-comedian and host

- Arnel Pineda, singer and the current vocalist of Journey

- Asiong Salonga, infamous gangster also known as the "King of Tondo"

References

- "Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- "Republic Act No. 409: AN ACT TO REVISE THE CHARTER OF THE CITY OF MANILA, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES". Official Gazette. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- Postma, Antoon (1992). "The Laguna Copper-Plate Inscription: Text and Commentary". Philippine Studies. 40 (2): 183–203. JSTOR 42633308.

- Joaqiun, Nick (1990). Manila, My Manila: A History for the Young. City of Manila: Anvil Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-9715693134.

- Potet, Jean-Paul G. (2013). Arabic and Persian Loanwords in Tagalog. p. 444. ISBN 9781291457261.

- Morrow, Paul. "The Laguna Copperplate Inscription". Archived from the original on 2008-02-05.

- Miguel de Loarca's Census of 1583

- Panganiban

- "Settlements & Growth". Creating Neighbourhoods and Places in the Built Environment. Taylor & Francis. 2 September 2003. p. 39. ISBN 1135817901.

- "SMC wrests control of port from Romero". Manila Standard. 18 February 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Endo, Jun (10 March 2017). "Mountain of garbage blights Manila". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "Tondo: The space in between". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "Tondo has highest crime rate in Manila". ABS-CBN (in Filipino). 21 August 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Santos, Mat (20 January 2018). "Celebrating the Feast of the Sto. Niño". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "DepED Manila Public Schools". Department of Education Manila. Department of Education Manila. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

Further reading

- Gaspar de San Agustin, Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas 1565-1615, Translated by Luis Antonio Ma�eru, 1st bilingual ed [Spanish and English], published by Pedro Galende, OSA: Intramuros, Manila, 1998

- Henson, Mariano A. 1965. The Province of Pampanga and Its Towns: A.D. 1300-1965. 4th ed. revised. Angeles City: By the author.

- Loarca, Miguel de. 1582. Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas. Blair and Robertson vol. 5 page 87:

- Panganiban, J.V. 1972. Diksyunaryo-Tesauro Pilipino-Ingles. Quezon City: Manlapaz Publishing Co.

- Mallat, Jean, Les Philippines: Histoire, Geographie, Moeurs, Agriculture, Idustrie, Commerce des colonies Espagnoles dans l'Oc�anie, Paris: Arthus Bertrand, Libraire de la Soci�t� de G�ographie, 1846

- Santiago, Luciano P.R., The Houses of Lakandula, Matanda, and Soliman [1571-1898]: Genealogy and Group Identity, Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 18 [1990]

- Scott, William Henry, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994

- Scott, William Henry, Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History, Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 1984

External links

- After Fishing in Tondo, Manila, oil on canvas by Fernando Amorsolo, 1927. 58.4 x 96.5 cm.

- Casas de Pescadores en Tondo ("Fishermen's Houses, Tondo"), oil on canvas by Fabian de la Rosa, 1928. 50 x 70 cm.

Media related to Tondo, Manila at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tondo, Manila at Wikimedia Commons