Tylopoda

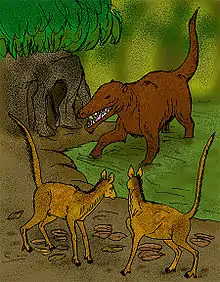

Tylopoda (meaning "calloused foot")[1] is a suborder of terrestrial herbivorous even-toed ungulates belonging to the order Artiodactyla. They are found in the wild in their native ranges of South America and Asia, while Australian feral camels are introduced. The group has a long fossil history in North America and Eurasia. Tylopoda appeared during the Eocene around 46.2 million years ago.[2]

| Tylopoda | |

|---|---|

| |

| A dromedary camel | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Suborder: | Tylopoda Illiger, 1811 |

| Families | |

|

Camelidae | |

Tylopoda has only one extant family, Camelidae, which includes camels, llamas, guanacos, alpacas and vicuñas. This group was much more diverse in the past, containing a number of extinct families in addition to the ancestors of living camelids (see below).

Taxonomy and systematics

Tylopoda was named by Illiger (1811) and considered monophyletic by Matthew (1908). It was treated as an unranked clade by Matthew (1908) and as a suborder by Carroll (1988), Ursing et al. (2000) and Whistler and Webb (2005). It was assigned to Ruminantia by Matthew (1908); to Artiodactyla by Flower (1883) and Carroll (1988); to Neoselenodontia by Whistler and Webb (2005); and to Cetartiodactyla by Ursing et al. (2000) and by Agnarsson and May-Collado (2008).[4][5][6]

The main problem with circumscription of Tylopoda is that the extensive fossil record of camel-like mammals has not yet been thoroughly examined from a cladistic standpoint. Tylopoda is a highly distinctive lineage among the artiodactyls, but its exact relationships are somewhat elusive because the six living species are all closely related and can be considered "living fossils", the sole surviving lineage of a prehistorically wildly successful radiation. More recent studies suggest that tylopods are not as closely related to ruminants as traditionally believed, expressed in cladogram form as:[7]

| Artiodactyla |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tylopoda are extremely conservative in their lifestyle and (like ruminants) seem to have occupied the same ecological niche since their origin over 40 million years ago. Thus, it seems that the previous assumption of a close relationship between Tylopoda and ruminants is simply because all other close relatives (whales, pigs etc.) are so divergent in their adaptations as to have obscured most indications of relationship, or at least those visible to phenetic analyses. However, the rather basal position that Tylopoda appears to have among the even-toed ungulates and relatives means that the oldest members of this lineage are still morphologically very primitive and hard to distinguish from the ancestors of related lineages. The first major modern and comprehensive analysis of the problem (in 2009) supported this; while some taxa traditionally considered Tylopoda could be confirmed to belong to this suborder (and a few refuted), the delimitation of this group is still very much disputed despite (or because of) an extensive fossil record.[7]

The taxa currently assigned (with some reliability) to Tylopoda are:[7]

Basal and incertae sedis

- Genus †Gobiohyus?

- Family †Homacodontidae

Superfamily †Anoplotherioidea

- Family †Anoplotheriidae

- Family †Cainotheriidae

- Family †Dacrytheriidae

Superfamily Cameloidea

- Family †Oromerycidae

- Family Camelidae

Superfamily †Merycoidodontoidea (=Oreodontoidea)

- Family †"Agriochoeridae" (paraphyletic)

- Family †Merycoidodontidae

Superfamily †Xiphodontoidea

- Family †Xiphodontidae

Disputed Tylopoda

Several additional prehistoric (cet)artiodactyl taxa are sometimes assigned to the Tylopoda, but other authors consider them incertae sedis or basal lineages among the (Cet)artiodactyla:

- Family †Antiacodontidae

- Family †Choeropotamidae (= Haplobunodontidae)

- Family †"Diacodexeidae" (paraphyletic)

- Family †Leptochoeridae

The Cebochoeridae and Protoceratidae, on the other hand, are prehistoric families that were occasionally placed within Tylopoda in the past, but are now considered more closely related to cetaceans and ruminants respectively than to camels.

References

- Donnegan, James (1834). "A New Greek and English Lexicon"

- PaleoBiology Database: Priscocamelus, basic info

- Fowler, M.E. (2010). "Medicine and Surgery of Camelids", Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. Chapter 1, General Biology and Evolution, addresses the fact that camelids (including llamas and camels) are not ruminants, pseudoruminants, or modified ruminants.

- Matthew, W. D. (1908). "Osteology of Blastomeryx; and phylogeny of the American Cervidae". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 24 (27): 535–562.

- R. L. Carroll. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York 1-698

- Ursing, B. M.; Slack, K. E.; Arnason, U. (April 2000). "Subordinal artiodactyl relationships in the light of phylogenetic analysis of 12 mitochondrial protein-coding genes". Zoologica Scripta. 29 (2): 83–88. doi:10.1046/j.1463-6409.2000.00037.x.

- Spaulding, M., O'Leary, M.A. & Gatesy, J. (2009): Relationships of Cetacea (Artiodactyla) Among Mammals: Increased Taxon Sampling Alters Interpretations of Key Fossils and Character Evolution. PLoS ONE no 4(9): e7062. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007062 article

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tylopoda. |

Data related to Tylopoda at Wikispecies

Data related to Tylopoda at Wikispecies- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.